Home » Jazz Articles » Under the Radar » Culture Clubs: A History of the U.S. Jazz Clubs, Part I:...

Culture Clubs: A History of the U.S. Jazz Clubs, Part I: New Orleans and Chicago

Early New Orleans Venues

Two blocks west of the French Quarter and adjacent to Congo Square, sits Basin Street. The location of low-income housing projects since the 1940s, the famous thoroughfare was the gateway to Storyville, a neighborhood that encompassed approximately five square city blocks. From 1897 to 1917, Storyville was the city's red-light district, designated as such by city officials in order to concentrate (and essentially ignore) almost every conceivable criminal activity in the city's statutes. Many local jazz musicians found their first venues in Storyville's saloons, bordellos, dance halls, hotels and restaurants, among them, King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Bix Beiderbecke, Buddy Bolden and many other names now lost to history. But Storyville and jazz, for all the urban mythology, was a short-lived marriage; with the start of World War I, segregated red-light districts were deemed as health hazards in areas where military bases were nearby. Storyville, to an increasingly diminished extent, continued to function into the 1930s at which time it was almost completely demolished to make room for public housing.

If the establishments of Storyville were the de facto jazz clubs of the era, the Mississippi and Ohio Riverboats were their evolutionary successors. King Oliver left New Orleans in 1918, largely due to the closing down of Storyville, but the move was likely exacerbated by a dance hall fight that led to his arrest. Oliver headed to north to Chicago where a number of New Orleans' popular players had gone before him. One of them, clarinetist and bandleader Lawrence Duhé, had come up through the ranks with Kid Ory and his musical timeline included a performance at the 1919 Chicago World Series—the infamous Black Sox Scandal. Duhé offered Oliver a spot in his Chicago group. By 1922, Oliver was leading his own his own band and had sent for his protégé—Armstrong—to join his Creole Jazz Band. In Jazz on the River (University of Chicago Press, 2005), William Howland Kenney documents his study of the riverboat's place in the geographic migration of jazz. One such riverboat, The Sidney, debuted in 1911 and was the first to feature a New Orleans band. Others, such as The Capitol and The Queen followed suit in making music, and dancing, a marketing incentive for cruises. For the black musicians, the cruises offered much more than their typical venues; extended engagements, relatively decent pay, and lodging—an evasive amenity in the South for black musicians.

While the relatively small footprint of the riverboat kept black musicians and white patrons in closer proximity, it was only in passing. The less than collegial confines of the boat played out as a microcosm of the Jim Crow South. A mutual sense of unease made for wild speculation; one patron interpreting Armstrong's scat singing as a threatening voodoo chant. Still, Armstrong and musicians such as Baby Dodds, Johnny Dodds, Red Allen, Lil Hardin Armstrong, Fate Marable and John St. Cyr played the boats cruising as far north as St. Louis or Saint Paul, Minnesota. Frequently, musicians would disembark and play for a night or two in one of those cities then ride the Illinois Central train to Chicago.

Chicago

The Chicago World's Fair of 1893 (also known as the World's Columbian Exposition), drew many ragtime musicians from the South, particularly pianists. The migration had set the stage for jazz musicians much the way the fair triggered an economic boon that built demand for dance halls and cabarets, especially on the city's south side. Hotels, in and around the Chicago Loop—the city's central business district—provided nightclub space for jazz acts. The Palmer House Hotel contained the Empire Room, the Stevens Hotel featured the Boulevard Room and the Panther Room was located in Sherman Hotel. These venues were primarily designed for big band dancing but also transmitted live radio broadcasts. The opening of independent clubs largely coincided with Prohibition, many functioning as speakeasies, typically located in, or just outside, the Loop.

The Green Mill and Early Chicago Jazz Clubs

Possibly the oldest jazz club in the U.S., The Green Mill is certainly the longest running establishment of its kind, opening in 1907 in Uptown Chicago, on Broadway. Originally known as Pop Morse's Roadhouse, it was taken over by an entrepreneur named Tom Chamales in 1910, and renamed as the owner's tribute to the Moulin Rouge in Paris. Charlie Chaplin, who had composed "Smile," a hit for Nat King Cole, would occasionally stop in for a drink when he was filming at a nearby studio. The visitors to come later were far more nefarious. During Prohibition the club was leased to the mob by its new owners, the Chamales Brothers, and a large stake in its ownership went to Jack "Machine Gun" McGurn, reportedly the principal gunmen in the St. Valentine's Day Massacre. McGurn was employed by Al Capone. Though Capone owned a speakeasy across the street, his chosen hangout was the Green Mill where bribes to the Chicago police allowed the bar to operate freely.

In the years of Prohibition, a gig at the Green Mill was a mixed blessing. A singer and comedian, Joe E. Lewis, failed to renew his contract with the club after a competing mob-run club offered him a more lucrative contract. The infamous mobster, Sam Giancana and two other Capone associates visited Lewis, leaving him for dead. Lewis, a crony of Frank Sinatra recovered eventually, and re-signed with the Green Mill while, McGurn, who ordered the hit, was himself, gunned down not long afterwards.

In the early years of the Green Mill, top-name talent included Ruth Etting, Billie Holiday, and Anita O'Day who all launched their careers, in part, by appearing at the club. In later years the club featured Shelia Jordan whose engagement was taken over by Patricia Barber and her quartet continues, in 2017, as the Monday night house band. Upcoming shows include the Dave Liebman Quartet, Matt Ulery's Loom Large and Kurt Elling. The club also features its After Hours Green Mill Quartet Jam Session, a relatively fixed group that performs weekend from midnight to five in the morning.

The Club DeLisa was a significant venue in the black community, opening in 1934 and featuring well-known artists such as Count Basie, Sun Ra, Albert Ammons, and Fletcher Henderson. The club remained open twenty-four hours a day and hosted a regular show with a mid-sized house band and gambling, discreetly hidden in the basement. The club burned down in 1941 but was quickly rebuilt, remaining open until 1958. It reopened as "The Club" in the mid-1960s with Cannonball Adderley's quintet being one of the first groups to perform there. Their album Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! Live at "The Club" (Capital, 1966) was described in liner notes as having been recorded at the Chicago venue when, in fact, it was recorded in Capital's studio.

The Friar's Inn was a well-known Chicago jazz venue in the 1920s, and like the Green Mill, it was a mob-run nightclub located on South Wabash in the Loop. The basement speakeasy was owned by Michael Fritzel who arrived in Chicago on a cattle train in 1898, worked as a bartender and later made the acquaintance of Al Capone. Fritzel was associated with more than one Chicago club, the common denominators being the mob and jazz. The New Orleans Rhythm Kings (originally called the Friar's Society Orchestra) was a group made up of New Orleans and Chicago musicians and were the most prominent performers at the club. Other acts included the Kansas City reed player Frank Teschemacher and saxophonist/clarinetist Bud Freeman.

The Jazz Showcase claims to be the oldest jazz club in Chicago despite opening decades after the Green Mill. Owned and managed by NEA Jazz Master Joe Segal, it has long been the venue for new talent as well as top names in jazz. Roy Hargrove, Chris Potter, James Carter, McCoy Tyner, Dexter Gordon, Count Basie, Kenny Burrell, Milt Jackson, Randy Weston, Bill Evans, Sun Ra, Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Sonny Stitt, Joe Lovano, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, and Ahmad Jamal constitute just a fraction of the well-known performers at the Jazz Showcase.

The HotHouse was a multi-purpose club on Balbo Avenue. With an immense main room and dance floor, the club hosted Roscoe Mitchell, Gil Scott-Heron, Henry Threadgill, Susie Ibarra, Dewey Redman and many others before losing its space in 2007. Since that time, HotHouse has continued to host events from remote locations but only a small percentage are jazz-specific.

Fred Anderson and the Velvet Lounge

I met the legendary free jazz/avant-garde saxophonist Fred Anderson on one of my visits to his Velvet Lounge on the Southside of Chicago. Anderson regularly made a point of greeting guests at his unassuming club on East Cermack, where the walls featured multiple portraits of Charlie Parker -Anderson's inspiration. The Louisiana native was self-taught on the saxophone and developed into an influential artist in the 1960s Chicago scene. Anderson was a founder and working member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). He established his career recording on two Joseph Jarman albums on the Delmark label: Song For (1967) and As If It Were the Seasons (1968). In the early 1970s Anderson formed his namesake sextet, a group that included trombonist George Lewis and drummer Hamid Drake. His first release as a leader was Another Place (Moers, 1978) and he went on to record twenty-five albums before his death in 2010.

Anderson made a conscious decision to stay close to his family and support them with a regular income, so in 1983, he purchased the Velvet Lounge. What made the club unique was its unabashed commitment to providing a Chicago venue dedicated to free jazz, the avant-garde and experimental music. Anderson himself performed frequently at the lounge and recorded three live albums on site. A fourth release A Night at the Velvet Lounge: Made in Chicago 2007 (Estrada Poznańska, 2009), was actually recorded in Poznań, Poland, at the second "Made in Chicago Festival."

Anderson mentored a number of younger musicians who have since become notable artists. Using the lounge as a platform, he had featured Drake, Harrison Bankhead, David Boykin, Nicole Mitchell, George Lewis, and Greg Ward among many others. Following Anderson's passing, the club was sold to new owners, who—while keeping the Velvet Lounge name—immediately discontinued jazz performances.

Andy's Jazz Club

Originally a saloon that catered to Chicago's booming newspaper publishing population, Andy's opened in 1951 north of the Loop. Entrepreneur Andy Rizzuto sold the property to an investment group in 1975 along with the rights to the name. The new owners introduced an extensive program of live jazz performances, and with the arrival of jazz promoters Penny Tyler and John Defauw in 1977, a three-times-daily schedule of "Jazz at Noon," "Jazz at Five" and "Jazz at Nine" was established. With its convenient location and a late afternoon show for commuters, Andy's became a Chicago institution.

The striking visual, upon entering Andy's, is its vast size. With rich wood, classic club lighting and exceptional acoustics, it is an ideal setting for the local talent that takes the stage seven days a week. Performers are most often local Chicago talent but top names such as Larry Coryell and Von Freeman have also played Andy's. On a night in September, 2014, I attended a show by trumpeter Marquis Hill, a winner of the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition who has gone on to record five albums as a leader. Relatively unknown at that time, Hill's development is emblematic of the opportunity for exposure that Andy's Jazz Club provides to young Chicago musicians.

Associated Recordings

Riverboat Jazz (Cool Note, 2008)

The pianist and bandleader Fate Marable utilized the Mississippi and Ohio River boats to a greater extent than any other jazz musician of the 1920s and 1930s. Unfortunately, little of his work was recorded on or off the paddle-wheelers. The Cool Note label did capture a bit (a scant twenty-four minutes) of some other notable performers of the era on this 2008 release.

The pianist and bandleader Fate Marable utilized the Mississippi and Ohio River boats to a greater extent than any other jazz musician of the 1920s and 1930s. Unfortunately, little of his work was recorded on or off the paddle-wheelers. The Cool Note label did capture a bit (a scant twenty-four minutes) of some other notable performers of the era on this 2008 release. Some of the more familiar names captured on Riverboat Jazz are King Oliver's Savannah Syncopators and Jelly Roll Morton's Levee Serenaders. Less known today are Dewey Jackson's Peacock Orchestra, Jimmy Wade & His Dixielanders, and Albert Wynn's Creole Jazz Band. Jackson had worked extensively in Marable's riverboat bands and continued playing on the river into the 1940s. Wade, a trumpeter, and trombonist Wynn recorded no more than three sides each as leaders in 1928, but both had enjoyed extended runs on the riverboat circuit.

Across the board, the tracks on Riverboat Jazz fall into the general area of "hot jazz" in that all display some combination of ragtime, blues, and brass band styles. Solos are limited and each of the six bands (Wynn leads two separate bands on the recording) are at least as rhythmically varied as necessary to maintaining listening interest.

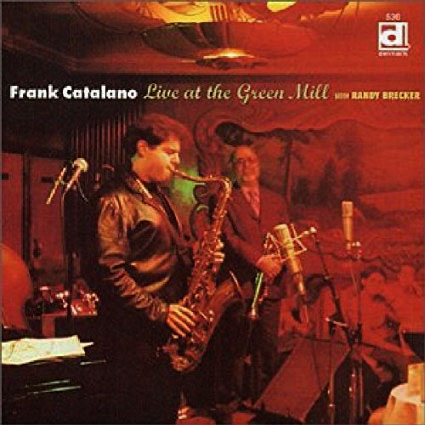

Frank Catalano: Live at the Green Mill (Delmark, 2002)

Tenor saxophonist Frank Catalano was just out of his teens when he recorded his second album You Talkin' To Me?! (Delmark, 2000) with Von Freeman. The Chicago native, whose style of choice has been compared to a latter-day Coltrane, incorporates modern elements that add a personal signature. Catalano's quintet on Live at the Green Mill features Randy Brecker and drummer Paul Wertico.

Tenor saxophonist Frank Catalano was just out of his teens when he recorded his second album You Talkin' To Me?! (Delmark, 2000) with Von Freeman. The Chicago native, whose style of choice has been compared to a latter-day Coltrane, incorporates modern elements that add a personal signature. Catalano's quintet on Live at the Green Mill features Randy Brecker and drummer Paul Wertico. On the opening piece, "Softly As in a Morning Sunrise" Catalano's blistering speed stops just short of spinning out of control. The Benny Golson standard "Killer Joe" take more time to unfold but eventually boils over with hard bop improvisation. The least known of the covers on Live at the Green Mill is the Medeski, Martin and Wood piece "Bubble House." Coltrane's "Impressions," while tailored to the leader, is respectful of the original. Catalano has an enormous sound and unremitting power and he's at home whether riotously swinging or searching in a more emotive vein.

There have been numerous live recordings that bear the "Live at the Green Mill" suffix and they cover an extensive range of styles. Bassist Eric Revis and his quartet, which featured Ken Vandermark, have been at the free improvisation end of the spectrum while the Monday night quartet of Patricia Barber's modern contemporary music embraces the other. The recording quality throughout the series is exceptional.

Fred Anderson: Timeless -Live At the Velvet Lounge (Delmark, 2006)

Shortly before tenor saxophonist Fred Anderson moved his Velvet Lounge from its crumbling South Indiana Avenue location to East Cermak Road, he released Timeless -Live At the Velvet Lounge. Bassist Harrison Bankhead played frequently at the Lounge and had later recorded The Great Vision Concert (Ayler Records, 2007) with Anderson. Drummer/percussionist Hamid Drake was a regular, and long-time Anderson collaborator participating in fifteen recordings dating back to Another Place (Moers, 1978).

Shortly before tenor saxophonist Fred Anderson moved his Velvet Lounge from its crumbling South Indiana Avenue location to East Cermak Road, he released Timeless -Live At the Velvet Lounge. Bassist Harrison Bankhead played frequently at the Lounge and had later recorded The Great Vision Concert (Ayler Records, 2007) with Anderson. Drummer/percussionist Hamid Drake was a regular, and long-time Anderson collaborator participating in fifteen recordings dating back to Another Place (Moers, 1978). The four extended pieces are improvised though Anderson's melodic lines often belie that. When he played without a chordal instrument he was sometimes given to a blustery style meant to fill the void, but on Timeless... he is at his most succinct and focused. Amderson's amazing range of agility has ample time to play out in these pieces that all run in double digits. The twenty-five minute title track that closes the album has Drake and Bankhead fueling Anderson's extended, circuitous improvisations with simmering and continuously changing rhythms.

In a slew of Anderson albums with "Velvet Lounge" in their title, Timeless... stands out as the best of the lot. Drake and Bankhead represented the next generation of transplanted Chicago music, both with substantial modern jazz pedigrees that intersected with that of the saxophonist. The fierce independence with which Anderson honed his unique style is evident in his playing on this album. His personal humility did not manifest itself in his playing, which is nothing, if not powerful.

The 1920s and early 1930s were the prime years of jazz development in Chicago. By the late 20s, the progression had moved on to New York, primarily in Harlem where the renaissance in black culture was developing. Part II of Culture Clubs goes east to the Cotton Club and beyond.

Tags

Under the Radar

Karl Ackermann

King Oliver

Louis Armstrong

Jelly Roll Morton

Bix Beiderbecke

Buddy Bolden

Kid Ory

Baby Dodds

Johnny Dodds

Red Allen

Lil Hardin

Nat King Cole

frank sinatra

Ruth Etting

Billie Holiday

Anita O'Day

Shelia Jordan

Patricia Barber

Dave Liebman Quartet

Matt Ulery

Kurt Elling

Count Basie

Sun Ra

Albert Ammons

Fletcher Henderson

Cannonball Adderley

Frank Teschemacher

Bud Freeman

Roy Hargrove

Chris Potter

James Carter

McCoy Tyner

Dexter Gordon

Kenny Burrell

Milt Jackson

Randy Weston

Bill Evans

Thad Jones

Mel Lewis

Sonny Stitt

joe lovano

Dizzy Gillespie

Art Blakey

Ahmad Jamal

Roscoe Mitchell

Gil Scott-Heron

Henry Threadgill

Susie Ibarra

Dewey Redman

Fred Anderson

Charlie Parker

Joseph Jarman

George Lewis

Hamid Drake

Harrison Bankhead

David Boykin

Nicole Mitchell

Greg Ward II

Larry Coryell

Von Freeman

Marquis Hill

randy brecker

Paul Wertico

benny golson

Medeski, Martin and Wood

Eric Revis

Ken Vandermark

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.