Home » Jazz Articles » Film Review » Best of the Best: Jazz From Detroit

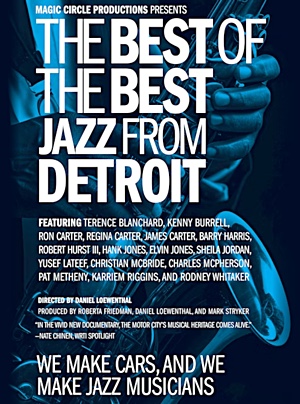

Best of the Best: Jazz From Detroit

It’s the sound of the factory, it’s the sound of the ghetto, it’s the sound of the church.

—George Bohanon

Best of the Best: Jazz From Detroit

Best of the Best: Jazz From DetroitMagic Circle Productions LLC

2025

The history of jazz music is told in hundreds of cities from coast to coast in America. From the cradle in New Orleans and the Mississippi River delta, the great migration of Black Americans northward spread the sounds that we know as the blues and jazz across the country. Millions headed to northern urban centers to escape the ravages of segregation and racial discrimination experienced in the Jim Crow South, hoping to find a lifestyle that provided a living wage and a thriving community for future generations. Many sought social reprieve, motivated by the epidemic of lynchings . Black Americans migrated to what were the largest cities in the Northeast, Midwest and West—New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Washington D.C., Los Angeles, San Francisco, and notably, Detroit. In a striking 90 minute presentation, Best of the Best: Jazz From Detroit tells the story of the Motor City's part in the jazz life line from swing to bebop to today's modern jazz, while offering the story of the city's resilient Black community and the culture that grew from the banks of the Detroit River, north to Paradise Valley. The film premiers on Prime Video on December 9.

It tells of the stunning amount of jazz greats from Detroit, of the rise and fall of a great industrial city, of "urban renewal" and urban decline. The film presents on a grand scale the soul of a great city that has strongly impacted jazz music and culture on an international scale. It defines Detroit as a music city that in many ways has no equal, a city whose musical winds have blown multi-directionally to contribute to the music in other great American music cities, such as the perceived modern epicenter of the music in New York.

As early as 1914, Detroit attracted Black workers with the promise of jobs in the thriving automobile industry. Henry Ford's offer of five dollars a day, a virtual doubling of factory wages at the time, was the first salvo fired that drew workers in droves northward. Ford, General Motors and Chrysler offered wages equal to what white workers were earning, allowing for the proliferation of a Black middle class. The offer made it easy for workers, tenant farmers and sharecroppers in the rural South to head north on "the first thing steamin.'" While wages were equal between Black workers and their white counterparts, the work itself was not. Work areas were segregated, with Black workers often performing the dirtier, more difficult work like painting, sanding and grinding. Neighborhoods were segregated as well due to racially restrictive covenants that dictated the mandate of home ownership for generations.

The Detroit auto industry provided a distinction from other northern urban centers in that Black workers could afford to buy homes, create businesses and provide superior education for their children. In musical terms, many families were able to have a piano in their home. The Black church provided a constant for the growth of the gospel sounds that fed the fire of blues music and its sophisticated cousin, jazz. Superior music education was available in integrated Detroit public schools, like the legendary program at Cass Tech High School. School and church were the mainstays of family life, with music being a major part of both.

Segregation brought with it the need to create business and culture within the Black community itself. From the southeast residential neighborhood of Black Bottom (named for the rich, black soil in the area) rose a business district to the north called Paradise Valley. Because there was ample income, night spots began to appear that provided locations for live music and the evolution of a sound, of an original approach to jazz that grew from the gospel sounds heard in the many churches now dotting the Black community in the Motor City. These spots employed musicians as well.

Soon, more than automobiles would be rolling off the assembly line in Detroit. Scores of jazz legends that include Elvin Jones, Yusef Lateef, Ron Carter, Paul Chambers, Milt Jackson, Betty Carter, Geri Allen and Charles McPherson came to be. Current jazz luminaries Kenny Garrett, Karriem Riggins and Regina Carter rose above the jazz horizon, mentored by the likes of Barry Harris, Marcus Belgrave and Rodney Whitaker. From this milieu evolved a distinct, soulful approach to jazz music that fed the creative fires of the Motown movement of the '60s and early '70s. "That's what we're about—we make cars and we make jazz musicians," says Whitaker, now at the helm of the jazz studies program at Michigan State University in nearby Lansing.

In 2019, longtime Detroit Free Press writer Mark Stryker published a definitive book, Jazz From Detroit that told the remarkable story of jazz in his home city. The award-winning effort virtually called for a film to be created on similar terms, to provide a visual narrative of one of the most important stories in the evolution of jazz music and Black culture. Teaming with director / producer Daniel Loewenthal and producer Roberta Friedman, a striking double portrait emerged, outlining Detroit's extraordinary jazz history and the city that produced it. The film chronicles the influences and accomplishments of the city's innovative jazz musicians, while telling the story of Detroit's dramatic rise and fall as an industrial center. It weaves together all of the elements of the resilient Black community that created the music and culture that impacted America's only genuine original art form. The film proudly displays the profoundly unique tradition of mentorship that has moved Detroit jazz into the modern age with strength and integrity. In essence, it connects the city's history with Black musical excellence.

The story weaves all of these elements that tell the story of Detroit jazz seamlessly, through interviews, performances and archival footage. With the challenge of including the immense volume and complexity of the story line and the narrative tributaries that spin off it in a 90-minute production, the film tastefully stresses the most important aspects in such a way that pulls the audience in hook, line and sinker. The simple fact is that Detroit's story is both fascinating and important, thereby of interest to anybody who has been inspired by jazz music and the great artists who produce it. It reveals a history both positive and negative that is common to most American urban centers from the '30s forward, both bearing the unique qualities that could only be discovered along the Detroit River and the city that came alive because of it.

The skillful use of narrators both from Detroit and other locations creates a narrative that is well-rounded, objective and painstakingly researched. Through current narration and archival footage, Detroiters Sheila Jordan, McPherson, Don Was, Alice Coltrane, Kenny Burrell, Harris, Belgrave, Whitaker, Hank Jones, Endea Owens, James Carter, Robert Hurst, Johnny O'Neal and many more contribute, offering insights only natives of the Motor City can provide. There is no gushing or cheerleading, just truth and understanding of what it means to be a Detroit musician, both at home and abroad. Jazz luminaries Christian McBride, Pat Metheny and Terence Blanchard share the bulk of the commentary provided from outside the reach of the city of Detroit, all with a reverence for and keen awareness of the rich history there as well as knowledge of its importance.

The film traces the lineage of sound in Detroit in terms of soul, a certain edge and a definite emphasis on original sound. Trombonist George Bohanon states, "It's the sound of the factory, it's the sound of the ghetto, it's the sound of the church." Bassist Owens adds, "Detroit is soulful, Detroit is vibrant, Detroit is patient, it's tough, it's kind." The Detroit sound is a blend of sophistication and raw blues, expressed with passion, intensity, and at times, aggression.

The film makes the point that the best of Detroit musicians, like the best musicians of any jazz city not named New York, eventually leave for Gotham and other points of light to further their careers. Many find that being from Detroit, a city with a great tradition of mentorship, is a plus in getting hired for performances and recording dates. If you are from Detroit, it is assumed that you are knowledgeable and driven by excellence. Violinist Carter refers to it being like a "Black American Express card." Bassist Hurst, who was mentored by both Harris and Belgrave, states that. "I carry my Detroit card proudly." It is considered a definitive truth that Detroit musicians have grit, bite and attitude.

When considering the remarkable roster of jazz musicians coming from Detroit, it is natural to wonder how this could have come to be. Writer/producer Stryker skillfully adds stories to the film, outlining this remarkable history. How the mantle of the great tradition of musicianship in the city has been passed from hand to hand explains how things have continued to grow and thrive creatively over time. Bassist Whitaker raises the point about jazz bass greats Paul Chambers and Carter being in the same homeroom at Cass Tech, and going on to be pillars of some of the greatest jazz bands in history. He realized he was a part of a great fraternity that gave him purpose. It transformed him and made him more serious about school and life.

Major contributions from strong female Detroiters are addressed prominently in the film, focusing on harpist Dorothy Ashby, Alice Coltrane, Betty Carter, Allen, Jordan and the under-appreciated piano /vibraphone phenom, Terry Pollard. Modern-day Detroit bassist Marion Hayden is eloquent in her narrative about her career and experiences with being a female musician in Detroit. She states, just as Whitaker does, that all that matters is, "Can you swing?"

Much time is given to the legacy of Harris, Belgrave and Whitaker as great mentors who have cast new generations of Detroit musicians into the jazz universe. The differences between their methodologies are akin to the variations on the theme of originality that is the Detroit sound. Blanchard points out that the unique striations of Detroit jazz are clearly delineated by the three Jones brothers, all of whom were very different and original in style. Hank was an elegant pianist with genius knowledge of melody and harmony who always wore a suit. Elvin led a tough life, was an ardent innovator and always dressed casually—often with a cigarette hanging from his lip. Thad was a great bandleader whose talent as a trumpeter was largely obscured by his allowing the cats in the band to play instead. All three, no matter what or how they were playing, played the blues. That is Detroit jazz expressed in simple, concrete terms.

The pivotal story within the story of Detroit is similar to many major US cities of the '50s and '60s in terms of what came to be known as "urban renewal." The film prominently tells the story of the impact of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, which completely devastated the Black Bottom and Paradise Valley neighborhoods, displacing families and destroying Black businesses. Once built, the highways literally paved the way for white Detroit residents to move to the suburbs and have an access point to move comfortably in and out of the downtown core. Detroit, once a city with a Black community, thus became a Black city, as it is today. Throughout the '50s, however, Black Bottom and Paradise Valley were the hubs of Black life, of Black culture in Detroit. Where the Paradise Valley business core was once located is now occupied by Comerica Park and Ford Field, where the Tigers and Lions play professional baseball and football.

Naturally, the film touches on the Motown phenomenon. It is a known quantity that Motown could never have happened without jazz. It was Detroit jazz musicians who performed on those classic recordings. It highlights musicians such as bassist James Jamerson, considered the "Charlie Parker of the electric bass," but does not overemphasize the pop phenomenon that Motown was and the fact that it left for the bright lights of Los Angeles in 1972. It does dive deeply into the urban decline of the mid to late '60s that saw the population of Detroit fall from a high of 2 million to the current day population near 640 thousand. The riots in the summer of 1967, which pitted Black neighborhoods against white cops, are chronicled, along with the election of the city's first Black mayor, Coleman Young. In essence, the film portrays Black culture and history in Detroit as a foundation to understanding the music that has resulted and continues to flourish.

As he did so eloquently in his award-winning book, Stryker emphasizes mentorship not only as a major factor in the history of the musical lineage explored in the film, but in the reason why the music today continues to have a strong pulse, enduring times of great hardship in the city. With Harris, Belgrave is a central figure in the story, from the formation of the Tribe collective in the early '70s to his most remarkable contribution, The Jazz Development Workshop. Along the way, he figured prominently as a trumpeter on classic Motown recordings while maintaining top-end acclaim as a jazz musician and mentor. Harris put mentorship into the DNA of Detroit Jazz, while Belgrave carried it forward. Neither stopped learning themselves. They established that helping each other is part of the legacy. Whitaker states, "I want to mentor folks who are going to mentor folks."

The Detroit Jazz Festival, the world's largest free jazz festival, is illuminated broadly as to its international reputation, but also to its discerning, no-nonsense audience. As a free festival, the barriers to access are lifted and the audience is real. McBride makes the point that the audience at DJF is knowledgeable, while Was offers, "The Detroit jazz audience will not accept any bullshit." The festival also provides a continuity of jazz culture in the city throughout the year, providing funding for a long list of jazz performance and education opportunities. While the festival attracts the biggest names of the genre, Detroit is always a central focus. It sheds light on the city as a major force in jazz music, both historically and in current times. It courses through the veins of all Detroiters, an annual reminder, an annual celebration of all Detroit has been and all it can be. It defines Detroit excellence and exudes love and fellowship to all who attend. It dispels the impression some have about Detroit's past, and provides steppingstones to a true realization of the city, its people and its culture.

Best of the Best: Jazz From Detroit is a beautiful touchstone for all things Detroit and the music that has risen from its iconic history. In presenting the stories of the many jazz greats that have been born and raised in the city, it also paints an intimate portrait of Black culture and community. It is a skillfully woven tale of great joy and great tragedy. It is a lovely soliloquy conceived and produced by proud Detroiters, those who have been strongly impacted by the soul of the music that has acted like a force of nature in southeast Michigan. The stories told are by many, yet the actual story line is seamless, unrelenting and unending, presenting itself as a tale that has yet to find a conclusion. The story is about jazz from a city that has had an impact on the vocabulary of the music, while not getting caught up in trends. It's a tale of continued vibrancy that has always overcome every obstacle placed before it. It states in no uncertain terms that it is soul that plays in Detroit.

Tags

Film Review

Barry Harris

Paul Rauch

United States

Washington

Seattle

Magic Circle Productions LLC

Elvin Jones

Yusef Lateef

Ron Carter

Paul Chambers

Milt Jackson

Betty Carter

Geri Allen

Charles McPherson

Kenny Garrett

Karriem Riggins

Regina Carter

Marcus Belgrave

Rodney Whitaker

Sheila Jordan

Don Was

Alice Coltrane

Kenny Burrell

Hank Jones

Endea Owens

James Carter

Robert Hurst

Johnny O’Neal

Christian McBride

pat metheny

Terence Blanchard

George Bohanon

Dorothy Ashby

Terry Pollard

Marion Hayden

James Jamerson

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.