Home » Jazz Articles » Building a Jazz Library » Saxophone Colossi: An Alternative Top Ten Banging Albums

Saxophone Colossi: An Alternative Top Ten Banging Albums

There is no way for jazz to go but to embrace new ideas. It will constantly change because there’s constantly a new us, new times. There will always be a fight from the conformists but they don’t represent where the tradition is coming from.

—Logan Richardson

This is an Alternative Top Ten. In order to allow room to celebrate some lesser known players, albums by Parker, Coltrane, Hawkins and Young have been excluded, along with those by a dozen or so other seminal players including Ben Webster, Albert Ayler, Paul Desmond and Ornette Coleman.

A few of the names in the honour roll are well known; Stan Getz is a household name, certainly, but his spotlighted album is a neglected masterpiece. The majority, however, are relatively obscure. They deserve to be more widely heard. And there are, of course, many, many other players who deserve a wider audience.

Hopefully, you will find one or two items which have so far slipped under your radar.

TEN ALTERNATIVE SAXOPHONE BANGERS TO SEIZE ON SIGHT

Wilton "Bogey" Gaynair

Wilton "Bogey" Gaynair Africa Calling

Candid, recorded 1960, released 2006

Jamaican-born tenor saxophonist Wilton 'Bogey' Gaynair, whose high-vaultage playing illuminated British hard bop in the late 1950s, is now pretty much a footnote in history. He released one head-charge of an album, Blue Bogey (Tempo, 1959), before disappearing into obscurity, or to be precise, into Germany, which was then the same thing. Yet if Blue Bogey and its follow-up, Africa Calling—released for the first time in 2006 following the collapse of the Tempo label in 1960—had been recorded for Blue Note, they would probably be in your collection today and Rudy Van Gelder would probably have remastered them. They really are that good. First generation London hard bop was by no means a slavish clone of its American inspiration. It tended, for instance, to use more major keys than its American parent. And it was typically more high-speed, too; the closest thing the pace gets to easing up on Africa Calling is the merely-mid-tempo "Rianyag." Trumpeter Shake Keane joins Gaynair in the frontline on Africa Calling and both albums are elevated by pianist Terry Shannon, Britain's answer to Horace Silver.

The New Don Rendell Quintet

The New Don Rendell Quintet Roarin'

Jazzland, 1961

This one does exactly what it says on the tin. Roarin' is a double-barrelled blast of full-strength British hard bop with a twin-saxophone frontline: Don Rendell on tenor and Graham Bond on alto. Rendell's unruly rough-edged tenor—he always placed emotional content above all else—is a joy. The even more feral Bond sounds like an amphetamine crazed Cannonball Adderley. He left Rendell in 1962, more or less putting down the saxophone in favour of the Hammond B3 (and as many narcotics as he could get his hands on). A year later he formed the straight-up R&B band Graham Bond Organization, which was at various times home to drummer Ginger Baker and guitarist John McLaughlin. But on Roarin', Rendell and Bond are still in lock-step. The album was produced in London by US producer Ed Michel (Jazzland was a subsidiary of Riverside), who went on to succeed Bob Thiele at Impulse! in 1969.

Stan Getz & Arthur Fielder & The Boston Pops Orchestra

Stan Getz & Arthur Fielder & The Boston Pops Orchestra At Tanglewood

RCA Victor, 1967

Stan Getz and the Boston Pops? It sounds like it might be a cheeser. But in fact, At Tanglewood is a serious affair. Its closest comparator is not the borderline easy listening of What The World Needs Now: Stan Getz Plays Burt Bacharach And Hal David (Verve, 1968) (on which Getz plays beautifully over a bland orchestral score), it is instead the all-round masterpiece Focus (Verve, 1961), on which Getz soared over a string ensemble on a suite written by the composer and arranger Eddie Sauter. Sauter is present again on At Tanglewood, contributing the fifteen minute "Tanglewood Concerto." Alec Wilder and David Raskin contribute other pieces, arranged by Manny Albam. Getz's regular band—vibraphonist Gary Burton, bassist Steve Swallow and drummer Roy Haynes, augmented by guitarist Jim Hall—are central to the proceedings. The album (recorded in concert) opens with Albam's up-tempo arrangement of Antonio Carlos Jobim's "The Girl From Ipanema," a showcase for Haynes. Then it is over to Sauter, Wilder and Raskin. And Getz. Sublime.

Getatchew Mekurya

Getatchew Mekurya Negus Of Ethiopian Sax

Buda Musique, 1972

Getatchew Mekurya evokes the ferocious energy of Albert Ayler (without the extended altissimo passages) and the primal glory of bar-walking tenor players such as Big Jay McNeely and Willis "Gator" Jackson. But Mekurya's style actually took shape years before he had heard any US music. It is based on a niche genre of traditional Ethiopian vocal music known as shellela, traditionally sung by warriors before going into battle. Mekurya developed his instrumental version while a member of the house band at Addis Ababa's Haile Selassie I Theatre in the mid 1950s. He took the shellela's origins seriously and performed wearing a shock-and-awe animal-skin tunic and lion's mane head-dress. Most of the pieces are played in three/four time, sometimes slow and menacing, at others fast and wild. "Shellela Besaxophone," the final track, is the single which made Mekurya a star in Ethiopia. Raw, abandoned and melismatic, Sun Ra's Arkestra might have sounded like this, if each player had taken a tab of Owsley's finest.

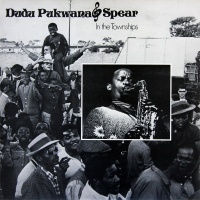

Dudu Pukwana & Spear

Dudu Pukwana & Spear In The Townships

Caroline, 1974

No recording could ever completely capture the shamanistic impact that was South African alto saxophonist Dudu Pukwana live on stage, any more than a recording could do the same for James Brown. But In The Townships makes a fine fist of it. Unlike Brown's carefully choreographed stage show, Pukwana's physically intense live performances were unscripted and wholly spontaneous, in symbiotic relationship with the low-end honks, raucous guffaws and moments of rhapsodic, tenderness that remind you, almost simultaneously, of Ornette Coleman and Johnny Hodges. Pukwana left South Africa with the multi-racial township-jazz band Chris McGregor's Blue Notes, who settled in London in 1966. His first own-name band, Spear , included two other Blue Noters in trumpeter Mongezi Feza and drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo, with fellow South Africans bassist Harry Miller and tenor saxophonist Bizo Mngqikana completing the lineup. Spear tilted the Blue Notes' even-handed mix of hard bop and kwela a little further towards the second ingredient and In The Townships, though recorded in London, transports you to apartheid era Cape Town with uncanny verisimilitude.

Clifford Jordan

Clifford Jordan Glass Bead Games

Strata-East, 1974

Tenor saxophonist Clifford Jordan recorded several masterpieces and near masterpieces in the mid 1970s and Glass Bead Games is the hands-down no-contest mother of them all. A double album recorded with two deeply empathic and interactive quartets over a single day, it is beyond any argument that almost mythical thing, A Perfect Jazz Album. Jordan had one of the great tenor voices, with an intimate, breathy sound which has something of both Ben Webster and Stan Getz, plus a fertile melodic imagination, an irresistible swing, and a deep feeling for the blues (the focus of the 1965 Atlantic album These Are My Roots: Clifford Jordan Plays Leadbelly). All these qualities are present and in full effect here. The band is similarly top ranking. Billy Higgins is the drummer in both quartets, Stanley Cowell and Cedar Walton are the pianists and Bill Lee and Sam Jones the bassists. These are also listening quartets: so interlocked are they that is often impossible to tell when a passage is pre-composed or collectively improvised. The twelve tunes include in Jordan's "Prayer To The People" and Cowell's "Maimoun" two of the most sheerly beautiful jazz ballads you are ever likely to hear (check the YouTube clip below). To round everything off, Jordan's production is immaculate. It is all, almost literally, breathtaking. Please, if you have not already done so, hear it.

Arthur Blythe

Arthur BlytheLenox Avenue Breakdown

Columbia, 1979

Alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe's roots-futurist chef d'oeuvre is also close to the peak of the overall jazz canon. An alumnus of pianist Horace Tapscott's Pan African Peoples Arkestra, Blythe co-produced Lenox Avenue Breakdown with ex-Impulse! / ex-Flying Dutchman producer Bob Thiele, with whom he had bonded during the recording of Tapscott's The Giant Is Awakened (Flying Dutchman, 1969). Multi-instrumentalist Howard Johnson once said that Blythe "could play the entire history of the music in one phrase." Add flautist James Newton, tuba player Bob Stewart, guitarist James Blood Ulmer, bassist Cecil McBee, drummer Jack DeJohnette and percussionist Guillermo Franco and things are really cooking. Incredibly, Lenox Avenue Breakdown was last reissued in the 1990s.

Larry "Stonephace" Stabbins

Larry "Stonephace" Stabbins Transcendental

Noetic, 2012

Larry Stabbins found his direction in jazz when, aged thirteen and playing in big bands in the west of England, he heard John Coltrane's Africa / Brass (Impulse!, 1961). Far from being a Coltrane revivalist, however, Stabbins was (he retired relatively young in 2015 and left London for a quieter life back in the west country) a restlessly inquisitive and experimental player. In the mid and late 1980s he co-led the politically active jazz-dance band Working Week with guitarist Simon Booth—the group's "Venceremos (We Will Win)" (Virgin, 1984) was the first of several singles to make the lower reaches of the British charts—and later recorded a series of electronic-infused albums. On Transcendental, which, sadly, proved to be Stabbins' swan song, he returns to his acoustic roots fronting a killer quintet comprising pianist Zoe Rahman, bassist Karl Rasheed-Abel, percussionist Crispin Robinson and drummer Pat Illingworth. The album opens with a magnificent take on Coltrane's "Africa" and seven Stabbins originals follow. Stabbins is at the top of his game, the lyrical and funky Rahman was (and still is) one of the most enjoyable pianists on the British scene, and Transcendental is a blast from start to finish.

Josephine Davies

Josephine DaviesHow Can We Wake?

Whirlwind, 2020

Compared to many of the other premier-league bands in London in 2021, tenor saxophonist Josephine Davies' trio Satori has attracted relatively little noise. There has been none of the social media ballyhoo that has surrounded, for instance, bands led by fellow tenors Nubya Garcia and Shabaka Hutchings. This may be because, unlike many of its contemporaries, Satori's style, though rhythmically rich, is not infused with dancefloor-friendly grooves: Davies looks instead to Zen philosophy for part of her inspiration. But make no mistake, Satori, a semi-free group which eschews harmonic structures, is among the best young bands in London. How Can We Wake?, the group's third album, is cerebral and nuanced and laden with exalted lyricism. And it has sinew, too—Davies has an exhilarating grasp of mid and low-end multiphonics and other tonal distortions. It is hard to nail her influences down but Sonny Rollins is definitely in the mix.

Logan Richardson

Logan RichardsonAfroFuturism

WAX Industry, 2020 / Whirlwind, 2021

In a 2016 interview, Kansas City-born alto saxophonist Logan Richardson said: "There is no way for jazz to go but to embrace new ideas. It will constantly change because there's constantly a new us, new times. There will always be a fight from the conformists but they don't represent where the tradition is coming from." Richardson was talking not long after the release of his Blue Note album, Shift. Though venturesome, that excellent disc sounds positively conservative compared to AfroFuturism. Among the latest album's melange of conceptual references, either intended by the artist or imagined by the listener, are flautist Nicole Mitchell's Afrofuturist composing paradigm, her fellow AACMer alto saxophonist Matana Roberts' Coin Coin series (Constellation, 2011-2019) and its use of field and archive recordings by the elders (and others), and, on around half the tracks, the epic scale of tenor saxophonist Kamasi Washington's orchestrations. This last quality Richardson achieves by overdubbing members of his octet rather than, as in Washington's case, assembling a band as big as the one required to perform Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen. Add a simulated string section, Björk / Kate Bush's lovechild, and echoes of Radiohead, trap and prog rock, and you are still skimming the surface. AfroFuturism is an album crying out to be the soundtrack for a movie. Ideally this would be a visual tone-poem along the lines of director Godfrey Reggio's collaboration with Philip Glass on Koyaanisqatsi, for it needs no narrative device to tell its story. Meanwhile, Richardson is rattling the jazz cage. Lord knows what the conformists will make of it all. But an earlier Kansas City-born alto saxophonist might well have applauded.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.