Home » Jazz Musicians » Sonny Rollins

Sonny Rollins

It’s no state secret that Sonny Rollins has never been fond of the recording studio. Never mind that he’s recorded his full share of gems there—not only early, celebrated albums such as Saxophone Colossus and Way Out West, but also digital-era efforts such as Old Flames and This Is What I Do. The man often embraced as the greatest living improviser requires too much creative freedom to start playing, as he puts it, “when the red light comes on.” And his perfectionism makes it difficult, sometimes painfully so, to go through multiple takes in search of what he thinks is the least flawed one.

But in Rollins’s preferred element—on stage, in front of an adoring crowd, free to follow his every impulse and dazzle with his inventions—he is fully at home. And that’s not just because in those situations this iconic tenor saxophonist is unencumbered by time restraints and issues in the control booth. The best thing about performing for him, by far, is seeing how happy his playing makes all the excited people who turn out to see him. The next best thing is making some of those performances—ones “that present parts of me I want to have presented”—available on record to his fans. With the expert help of longtime associate Richard Corsello, his engineer at Fantasy during the 1980s, that’s what Rollins has been doing with his remarkable Road Shows series, an ongoing collection of concert highlights being released on his own Doxy Records label. Road Shows, vol. 1, which came out in 2008, was largely drawn from superfan Carl Smith’s tapes, spanning nearly 30 years. It climaxed with a 2007 performance of “Some Enchanted Evening” by a trio for the ages featuring Roy Haynes and Christian McBride. All of the music on the second volume, released in 2011, was recorded in 2010, including highlights from Rollins’s 80th birthday concert, featuring his first-ever encounter with Ornette Coleman. Road Shows, vol. 3—which is being distributed under the terms of a new agreement by Sony Music Masterworks through its revived jazz imprint, OKeh Records—was recorded between 2001 and 2012 in Saitama, Japan; Toulouse, Marseille, and Marciac, France; and St. Louis, Missouri. It features a familiar core band including pianist Stephen Scott, trombonist Clifton Anderson, and Rollins's bassist of a half-century, Bob Cranshaw, with Bobby Broom and Peter Bernstein alternating on guitar; Kobie Watkins, Perry Wilson, Steve Jordan, or Victor Lewis on drums; and Kimati Dinizulu or Sammy Figueroa on percussion.

Read moreTags

Tribute To Living Legend Sonny Rollins; Other Birthdays This Week--Roy Ayers, Harry Connick Jr, and More

by David W. Daniels

Tribute to Sonny Rollins--his compositions as interpreted by other jazz musicians, including Jim Hall and Ron Carter, Lambert/Hendricks/Ross, Ted Curson and more. Two compositions from Sonny Rollins' best known albums. Other jazz musicians' birthdays, including David Sanchez, Maria Muldaur, Baby Face Willette and more. Playlist John Coltrane “Like Sonny" from The Heavyweight Champion: The Complete Atlantic Recordings (Compilation) (Atlantic) 00:00 Jim Hall and Ron Carter “St. Thomas" from Alone Together (Milestone) 8:33 Don Patterson with Booker Ervin “Oleo" ...

Continue ReadingCarla Bley, Count Basie, Diane Schuur, Hubert Laws & Sonny Rollins

by Joe Dimino

Welcome to the 900th episode of Neon Jazz! After 14 incredible years, we've hit yet another milestone--one that wouldn't be possible without the legends who have shaped jazz and the fans who've supported us every step of the way. For this special hour, we take a deep dive into the icons who have defined the sound of jazz and graced our interview series. We begin with the saxophone giant Sonny Rollins, featuring music from his brand-new 2024 album The Complete ...

Continue ReadingJazz Interpretations Of Jerome Kern, Part II

by Larry Slater

The second hour of “jazz Interpretations of the music of Jerome Kern" featured tunes from the 1930s: “Yesterdays," “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes," “I Won't Dance," “A Fine Romance," “The Way You Look Tonight" and “All The Things You Are." Jerome Kern was at the peak of his powers during the '30s, and these jazz standards have stood the test of time to become part of the jazz vocabulary. ...

Continue ReadingMy Summer with Sonny

by Patrick Burnette

Raise your hands, jazz fans, if you've been thinking about jazz legend Sonny Rollins during the last few months. After all, the great man is still with us at age 94. Reaching such an age is an accomplishment for anybody, but a miraculous feat for an African-American jazz musician born in the early decades of the twentieth-century, who saw so many of his predecessors and peers die young from drugs, alcohol, hard living, and the stresses of omnipresent racism. Rollins ...

Continue ReadingMy Summer with Sonny: The Podcast

by Patrick Burnette

Summer's winding down. How'd you spend yours? Pat spent his immersed in the music and life of Sonny Rollins, one of the greatest improvisers to grace the story of jazz. In this podcast, which is kind of an upcoming article in summary (and audio) form, Pat looks at the massive new biography of Sonny as well as four recent reissues of some of his best loved music, most of which involve trios.Playlist Discussion of Aidan Levy's book Saxophone ...

Continue ReadingThelonious Monk: Brilliant Corners

by Richard J Salvucci

Writing about being “lost for words" is not the ideal way of starting a review, but it may be the plain truth. Perhaps Thelonious Monk is an acquired taste. Perhaps not. Whatever the case, this particular release of Brilliant Corners is just that--brilliant.The whole package is superb and really defines Craft Recordings “Small Batch" vinyl series. The technical literature accompanying the recording says “Each edition is cut from its original analog tapes by Bernie Grundman and pressed on ...

Continue ReadingSonny Rollins: Go West! The Contemporary Records Albums

by Richard J Salvucci

Apparently, the median age of a jazz listener is in his or her mid to late 40s. So, perhaps, the representative listener was born in the mid-1970s. Sonny Rollins first recorded in 1949. The recordings reviewed here were made in the late 1950s, well before many contemporary listeners were born. While there have been ample reissues of Rollins' work, most coincided with the still-active phase of his career. Much of his work has appeared since “Skylark" on The Next Album ...

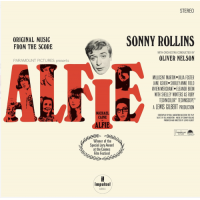

Continue ReadingBackgrounder: Sonny Rollins - Alfie (1966)

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

No album better reflects Sonny Rollins's personality than his Alfie: Original Music From the Score, arranged by Oliver Nelson. Recorded in New York in January 1966, the original music has his energy, passion, tenderness and his melancholy in one fell swoop. It's all very mid-1960s. To learn more about the recording, consult my two-part post on The Making of Alfie, from 2010. The first part was devoted to the popular song by Hal David and Burt Bacharach and the second ...

read more

Dazzling Live Sides By Sonny Rollins Receive First Authorized Release On Resonance's Record Store Day Offering 'Freedom Weaver: The 1959 European Tour Recordings'

Source:

Terri Hinte Publicity

Resonance Records, the award-winning home of archival jazz treasures, will proudly present a new, fully authorized live collection by tenor master Sonny Rollins, Freedom Weaver: The 1959 European Tour Recordings, as a limited edition four-LP set on Record Store Day, April 20. Never before issued as a legitimate release, these much-bootlegged sides—which feature Rollins, at the height of his early powers, with bassist Henry Grimes and drummers Pete La Roca, Kenny Clarke, and Joe Harris—will subsequently reach stores as a ...

read more

Backgrounder: Sonny Rollins Plus 4

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

The sound of the Clifford Brown-Max Roach Quintet on their studio recordings for EmArcy starting in 1954 was unmistakable. Trumpeter Brown's pointed and lyrical blowing combined with Roach's restless drums and the deliberate sound of Harold Land's tenor saxophone poured the foundation for a new daring and elegant form of hard bop. By 1956, tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins had replaced Land. He did so after turning down Miles Davis's offer to join his quintet (John Coltrane would take the job). ...

read more

Jazz Musician of the Day: Sonny Rollins

Source:

Michael Ricci

All About Jazz is celebrating Sonny Rollins' birthday today!

It’s no state secret that Sonny Rollins has never been fond of the recording studio. Never mind that he’s recorded his full share of gems there—not only early, celebrated albums such as Saxophone Colossus and Way Out West, but also digital-era efforts such as Old Flames and This Is What I Do. The man often embraced as the greatest living improviser requires too much creative freedom to start playing, as he ...

read more

Backgrounder: Sonny Rollins Plays for Bird, 1957

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

Sonny Rollins idolized Charlie Parker, as did all saxophonists in the late 1940s. But for Sonny, Parker was more of a mentor, someone to impress and seek his approval. Sonny achieved that in 1953, when he recorded with Parker and Miles Davis for Prestige. At the time, Parker was under contract to Norman Granz's Norgran label, so he recorded on tenor saxophone instead of alto and was listed as Charlie Chan on the session and recording. Parker would die two ...

read more

Jazz Musician of the Day: Sonny Rollins

Source:

Michael Ricci

All About Jazz is celebrating Sonny Rollins' birthday today!

It’s no state secret that Sonny Rollins has never been fond of the recording studio. Never mind that he’s recorded his full share of gems there—not only early, celebrated albums such as Saxophone Colossus and Way Out West, but also digital-era efforts such as Old Flames and This Is What I Do. The man often embraced as the greatest living improviser requires too much creative freedom to start playing, as he ...

read more

Jazz Musician of the Day: Sonny Rollins

Source:

Michael Ricci

All About Jazz is celebrating Sonny Rollins' birthday today!

It’s no state secret that Sonny Rollins has never been fond of the recording studio. Never mind that he’s recorded his full share of gems there—not only early, celebrated albums such as Saxophone Colossus and Way Out West, but also digital-era efforts such as Old Flames and This Is What I Do. The man often embraced as the greatest living improviser requires too much creative freedom to start playing, as he ...

read more

Sonny Rollins: In Holland, 1967

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

In 1967, Sonny Rollins was restless. Everything in the U.S. was changing fast. As an artist, Sonny was changing, too. Just as he had was reaching the apex of his playing prowess, jazz seemed to be sliding as a valued art form at home. To find truth, Sonny toured extensively in Europe, particularly Scandinavia and the Netherlands. There, he found emotionally open fans who understood his history and fully accepted his art and heritage. Back in the U.S., what seemed ...

read more

Jazz Musician of the Day: Sonny Rollins

Source:

Michael Ricci

All About Jazz is celebrating Sonny Rollins' birthday today!

It’s no state secret that Sonny Rollins has never been fond of the recording studio. Never mind that he’s recorded his full share of gems there—not only early, celebrated albums such as Saxophone Colossus and Way Out West, but also digital-era efforts such as Old Flames and This Is What I Do. The man often embraced as the greatest living improviser requires too much creative freedom to start playing, as he ...

read more

Sonny Rollins at 90

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

Today is Sonny Rollins's 90th birthday. I never talk to Sonny on his birthday. I know how he feels about this day. It brings too much attention to him, and Sonny is happiest off the grid. But that doesn't mean I cant write about him. My bond with Sonny goes back to to an afternoon we spent in the summer of 2010 just before his 80th birthday. I had just started writing for The Wall Street Journal and came up ...

read more