Home » Jazz Articles » Highly Opinionated » My Summer with Sonny

My Summer with Sonny

Raise your hands, jazz fans, if you've been thinking about jazz legend Sonny Rollins during the last few months. After all, the great man is still with us at age 94. Reaching such an age is an accomplishment for anybody, but a miraculous feat for an African-American jazz musician born in the early decades of the twentieth-century, who saw so many of his predecessors and peers die young from drugs, alcohol, hard living, and the stresses of omnipresent racism. Rollins began recording as a leader in 1953, when giants like Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and Charlie Parker still walked the earth. He put down his horn almost 60 years later in 2012. He had longer innings than almost any other major figure in jazz, up to and including the fantastically prolific Duke Ellington. But Rollins' career baffles jazz fans as much as it inspires awe, with its voluntary exiles from the scene, its changes of direction, its controversial choices in the studio.

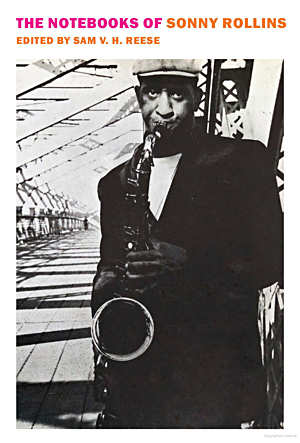

Raise your hands, jazz fans, if you've been thinking about jazz legend Sonny Rollins during the last few months. After all, the great man is still with us at age 94. Reaching such an age is an accomplishment for anybody, but a miraculous feat for an African-American jazz musician born in the early decades of the twentieth-century, who saw so many of his predecessors and peers die young from drugs, alcohol, hard living, and the stresses of omnipresent racism. Rollins began recording as a leader in 1953, when giants like Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and Charlie Parker still walked the earth. He put down his horn almost 60 years later in 2012. He had longer innings than almost any other major figure in jazz, up to and including the fantastically prolific Duke Ellington. But Rollins' career baffles jazz fans as much as it inspires awe, with its voluntary exiles from the scene, its changes of direction, its controversial choices in the studio. Rollins has always commanded an audience, and his work has rarely gone out of print, but a number of factors have increased his music's profile the last few years. For one, his catalog is beginning to benefit from the ongoing vinyl revival, with several works from the mid to late nineteen-fifties (for many listeners, his best loved period) being released in newly mastered editions in deluxe packaging. The booklets accompanying these reissues include the usual commentary from critics and peers but also incorporate insights from the man himself, an especially gratifying development given how reticent Rollins could be in the past. Selections from his notebooks were published just this year in The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins (New York Review Books, 2024). And then, of course, there is the elephant in the room, Aidan Levy's Saxophone Colossus: The Life And Music Of Sonny Rollins (2022, Hachette Books).

Levy's biography—all 720 colossal pages of it—requires a serious commitment on the part of his readers, and the various vinyl issues require no small outlay of money and shelf space. What can this flood of material tell us about jazz's most enigmatic genius?

Let's begin with the doorstopper. Some biographers are forced to supplement limited primary sources about their subject with contextual information about the person's historical and cultural milieu (think biographies of Shakespeare). Levy, who spent years assembling his extensive sources, confronts the opposite problem—a still living subject with amply documented public records, interviews, and living contemporaries. His research seems to have unearthed more facts than could be included in a small library, much less a tome running a mere 700 pages. In fact, the footnotes accompanying this incredible feat of persistence run an additional several hundred pages and are available only as a separate downloadable PDF from the publisher's website, presumably because their inclusion in the physical published book would have rendered it an ungraspable cuboid.

Saxophone Colossus is both insightful and frustrating, readable and exhausting. Time and time again, Levy's narrative gives fresh insights into Rollins' character and art, and any listener interested in the great saxophonist's music is encouraged to seek the book out with all speed. But one also has the sense that too often the sheer volume of research overwhelms Levy's ability to separate facts providing insight and understanding and those that, while certainly factual, might be better omitted. No biography, no matter how long, can tell a reader every detail about its subject's life without taking the same duration as that life (or longer) to read. The art of selection is crucial. Every biographer editorializes by necessity. Some just do so more artfully than others.

Saxophone Colossus is both insightful and frustrating, readable and exhausting. Time and time again, Levy's narrative gives fresh insights into Rollins' character and art, and any listener interested in the great saxophonist's music is encouraged to seek the book out with all speed. But one also has the sense that too often the sheer volume of research overwhelms Levy's ability to separate facts providing insight and understanding and those that, while certainly factual, might be better omitted. No biography, no matter how long, can tell a reader every detail about its subject's life without taking the same duration as that life (or longer) to read. The art of selection is crucial. Every biographer editorializes by necessity. Some just do so more artfully than others. The early chapters of Saxophone Colossus are hard going. Levy spins out paragraphs where sentences would have sufficed. It's certainly questionable, to give one example, that we need to know the height of Rollins' various ancestors in inches. Some of the background, however, is crucial. Levy recites at length the miserable treatment of Sonny's father, Walter Rollins Sr., a chief steward at an officer's club court-marshalled for crossing the color line. Here the details offered seem to offer a crucial key to Sonny's lifelong political awareness and suspicion of others. Frustratingly, however, Sonny's father then disappears from the narrative for hundreds of pages, and when his presence is mentioned at a concert of Sonny's taking place decades later, the reader is shocked to learn that Sonny's father is still alive.

The shape of the narrative is a narrowing cone, with the bulk of the work devoted to Sonny's career in the fifties and sixties, and a growing sense of acceleration and telescoping of narrative after the turn of the seventies. Roughly 350 pages, or slightly less than half of the narrative, is devoted to Sonny's career after his 1960-61 sabbatical (Sonny took several of these breaks from the business, with the Williamsburg Bridge episode of self-isolated practice the most famous). His career and life after 1970 are compressed into 200 pages. To some degree this compression makes sense, as most listeners value Sonny's work in the fifties and sixties the highest, but there is also the feeling that Levy realizes that he is running out of time to get the book finished and needs to wrap things up. Given the scope of the project, it's hard not to be sympathetic to his plight.

From the seventies forward, the book loses a bit of shape, and one senses that Rollins' career does as well. The saxophonist's various albums on Milestone from that era are all touched upon, but recognizing that Rollins' reputation during this period was based on his live appearances, Levy lists and describes gig after gig after gig—who attended, what shape Rollins' teeth were in (the saxophonist suffered from ongoing dental problems), what songs were played and for how long (spoilers—VERY long) and, strangest by far, what clothing Sonny was wearing at the gig. Sonny's mohawk will always have a place in all right-minded people's hearts, but color and fabric of the pullover he wore to concert number eighteen of 1972 might have been omitted with no harm done.

Saxophone Colossus is a miracle of research, of detail assembling, of quotations giving us a flavor of the thinking and values of its most unusual subject. It does not provide as much analysis as one would wish. There is little explanation, for instance, of what made Rollins such an incredible improvisor. We learn that he practiced incessantly, that he had an incredible rhythmic sense, that he tongued almost every note (quite unusually for a jazz musician). But aside from glancing mentions of John Coltrane, whose much briefer and even more meteoric career seemed to overshadow Sonny's by the end of the fifties, and even briefer cameos by Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins, one has little sense that other saxophone players even existed during Sonny's career.

It might have been instructive, for instance, to have compared Rollins' art to that of Sonny Stitt's (there are an amazing numbers of "Sonny's" in jazz, just counting the saxophonists—Rollins, Stitt, Criss, Simmons, Fortune...). Stitt was a mere six years older than Rollins. He came out of the bebop tradition, like Rollins. He was a combative soloist known for his ability to win cutting contests, like Rollins. He frequently, though not exclusively, played tenor saxophone due to invidious comparisons to Charlie Parker when he played alto instead. During his much shorter lifetime, he recorded more extensively than Rollins year by year. And, yet, Stitt is little remembered or studied today and it's a fair bet he will never get a biographical brick of his own. What made Rollins a genius of improvisation and Stitt a journey-man? One doesn't expect Levy necessarily to answer this question, though it would be nice if he had. The problem is that while reading his biography of Rollins, it's not apparent that he even considered it.

All that said, here are some takeaways from the book. Feel free to use them like Cliff Notes should you be too intimidated to read the tome itself, but it will be more fun to come to your own conclusions, which may be very different from these.

- Rollins practiced as obsessively as Coltrane. If asked whether Coltrane or Rollins had more "natural" talent, the answer seemed obvious—Rollins did. He matured into a major soloist more quickly than Coltrane. His solos were more purely inventive than Coltrane's, which drew heavily on scaler exercises and, in the "Giant Steps" era, formulas needed to negotiate the breakneck harmonic labyrinth of the "Coltrane Changes." Coltrane was famous for his obsessive practice (between sets at the club; between takes at the studio). Rollins, especially after the famous "Bridge" sabbatical, turns out to have been just as obsessive, if not more so. Who would have guessed? And, given how much technical mastery Rollins had at his disposal in the fifties, why exactly was he so obsessive?

- Rollins was a lone wolf. The story leading up to the Bridge sabbatical, and even more after that sabbatical, seems to be that of Rollins' increasing dissatisfaction with himself and, just as crucially, other musicians. When Rollins feels musically stymied, his solution tends to turn inward—more practice by himself, sometimes for months or years at a stretch. Occasionally a fellow musician might be allowed to join him, and the narratives of these rare instances follow a pattern: the musician learns a lot by observation but ends up exhausted by Sonny's indefatigability. But Sonny does not seem particularly inspired by his work with other musicians. Whereas Coltrane searched out collaborators throughout his truncated career—Elvin Jones, Rashid Ali, Alice Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Pharoah Sanders—Rollins burned through band members like match sticks. The people who are allowed to stay on—say, bassist Bob Cranshaw—do so for reasons oblique to the average listener.

- Rollins "solved" bebop and never really deserted it. Reading about Rollins career in its whole arc makes clear that bebop is his home. For most musicians, bebop was a necessary corrective to the subordination of improvisation in the increasingly commercialized (and white) world of big band music. But its emphasis on virtuosity at the expense of other musical values (a good tune, an interesting arrangement, the joy of great band chemistry, the ability of music to create various moods) made it aesthetically unproductive for most musicians, who turned first to "cool" jazz and later to hard bop as a way of expanding their opportunities. For many musicians, bop's technical demands were hard to meet with truly interesting improvisations—things just moved too fast for them to play at their best. Rollins, in contrast, had no trouble with bebop's technical demands and choose to broaden the form rather than transforming it it. He uses the eighth note as his basic improvisational unit but always keeps the ability to unleash sixteenth-notes fantasias when the moment requires. Instead of returning obsessively to a few harmonic matrices (Rhythm changes, blues, Cherokee changes) like the first-generation beboppers, he shows that any obscure Broadway or pop tune can be grist for the mill. When cool jazz and hard bop come along, he shows little interest in them as new musical approaches. Hard bop, with its emphasis on group chemistry and minor-key originals (and its disinterest in standards and show tunes) is not for Sonny. Cool jazz is not for Sonny to almost laughable degree. Group chemistry—again, not something that particularly interests him. Miles Davis and Coltrane both kept their most celebrated units active for several years. Rollins went through three bands just putting together A Night at the Village Vanguard.

- Rollins was a perfectionist. The saxophonist's dislike of working in the studio is well known. What the biography makes clear, in quotations from Sonny himself, is that any perceived lack of perfection frustrated him. If a listener said he or she enjoyed a performance, Sonny always replied that it could have been better. Well, sure—it's hard to imagine a "perfect" improvised solo, much less a "perfect" jazz concert or album. But that's the price paid by a genre invested in spontaneous improvisation. It seems odd to demand "perfection" of oneself—or others—in jazz. More importantly, it's not clear demanding perfection in such a context is particularly aesthetically productive.

- Rollins post-fifties career shows an intensification of all the tendencies listed above in a way that seems to have stymied at least some of his seemingly limitless potential. During the bridge sabbatical, and after it, Rollins spent countless hours upon hours in the woodshed. He took greater control of his career and seemed willing to give up the benefits of working with a big label for the freedom to control, and eventually produce, his own recordings. A good deal of great music was the result of this discipline and self-management, but most listeners question whether the results post-Bridge match those of Sonny's apparently less prepared, perfected, and controlled fifties recordings. This is a paradox that Levy's book never addresses, though admittedly given the circumstances (a still living, brilliant, prickly main subject) it would be difficult for him to have done so.

Caveats aside, Saxophone Colossus is not to be missed by fans of jazz in general or Rollins in particular. Just be sure to set aside a weekend or three to plow through it.

What of the flood of recent reissues of Rollins' fifties albums? Should these too earn your time and hard-earned dollars? Below I look at four recent entries in the vinyl reissue sweepstakes, all of which feature Rollins in his favored piano-less trio format.

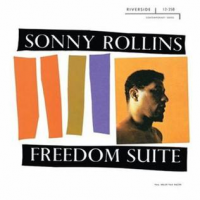

Let's begin with the least recent of the reissues, Vinyl Me Please's edition of Freedom Suite (Riverside 1958). For those unfamiliar with VMP, the label is run as a kind of club, with monthly subscriptions, but also sells some issues direct to the public. At least some record stores pick up VMP product and stock it for sale to whoever has the Benjamins. Prices tend to be high—$40 or more for what are typically all-analogue pressings on heavyweight vinyl with nicely-produced cardboard covers and, often, a mini-essay enclosed to give perspective on the release. Those of us old enough to remember the record and CD clubs of yore know how the old model worked. You got a handful of issues very cheaply and then were signed up for monthly purchases of whatever album the club was pushing (often with the right to opt out of a given selection). If you were disciplined enough at signing up and then quitting as soon as the agreement allowed, you could accumulate a stack of music pretty cheaply. The selections were not always the most exciting (and sometimes came in budget versions) but it was a great way to flesh out a collection. VMP's model is a high-end version of the old-style club. Pressings and covers are top notch, and the few examples I've accumulated are competitive with if not better than other AAA reissue programs (Mo-Fi, Blue Note, Acoustic Sound's Contemporary and Verve series, Speakers Corner, Pure Pleasure, etc). As a club, however VMP is working in a very different environment than its predecessors.

Let's begin with the least recent of the reissues, Vinyl Me Please's edition of Freedom Suite (Riverside 1958). For those unfamiliar with VMP, the label is run as a kind of club, with monthly subscriptions, but also sells some issues direct to the public. At least some record stores pick up VMP product and stock it for sale to whoever has the Benjamins. Prices tend to be high—$40 or more for what are typically all-analogue pressings on heavyweight vinyl with nicely-produced cardboard covers and, often, a mini-essay enclosed to give perspective on the release. Those of us old enough to remember the record and CD clubs of yore know how the old model worked. You got a handful of issues very cheaply and then were signed up for monthly purchases of whatever album the club was pushing (often with the right to opt out of a given selection). If you were disciplined enough at signing up and then quitting as soon as the agreement allowed, you could accumulate a stack of music pretty cheaply. The selections were not always the most exciting (and sometimes came in budget versions) but it was a great way to flesh out a collection. VMP's model is a high-end version of the old-style club. Pressings and covers are top notch, and the few examples I've accumulated are competitive with if not better than other AAA reissue programs (Mo-Fi, Blue Note, Acoustic Sound's Contemporary and Verve series, Speakers Corner, Pure Pleasure, etc). As a club, however VMP is working in a very different environment than its predecessors. Back in the old days, owning music physically was the only practical way to hear it "on demand" and keep reliable access to it. Given those circumstances, collectors tended to be less discriminating. Buying physical media is just what you did, so why not do so in bulk? Now, almost any piece of music can be heard streaming (free if you can endure the commercials) and letting another slab of vinyl into the home is a weightier proposition. Each purchase has a higher decision threshold, but clubs like VMP tend to limit selection and ask the member to just lay back and enjoy what's on offer. Buying the label's albums individually provides some flexibility, but ala cart the issues cost more than any other reissue series that doesn't come in two-disc / 45 rpm format. In short, how long VMP will be able to sustain its business model is unclear. All that said, VMP cuts a good record, and the copy of Freedom Suite on my turntable was flawlessly pressed. So if you have the dosh, get 'em while the getting's good (and the lights are still on at VMP headquarters).

Freedom Suite is the most problematic of Sonny's trio masterpieces. With Max Roach on percussion and Oscar Pettiford on bass, it's one of the last albums Rollins cut with musicians of similar stature to himself. Roach had been his boss in the Brown/Roach quintet, where Sonny replaced Harold Land and stayed on, briefly, after Clifford Brown's tragic death in a road accident. Roach is always a forceful personality on percussion and makes some definitive statements on the nineteen-minute suite that occupies side A of the album. Pettiford, no wilting violet himself, puts in a similarly strong showing. And Rollins the improviser can seemingly do no wrong in the second half of the fifties.

However, while Rollins' two-sentence blurb on the back of the album, which clearly called out racial injustice, was enough to rile up certain listeners, the musical motifs of "Freedom Suite" are not particularly incendiary and the tone of the performance is miles away from Roach's later, more confrontational "We Insist! Freedom Now Suite." It's great trio jazz and more than worth a listen. It's just the political framing doesn't fit comfortably. As protest music it rapidly got surpassed by later efforts (suite and non-suite) that took on racism much more directly.

The second side of the album includes four unlikely selections (why exactly include songs by Noel Coward and Meredith Wilson?) and ends with a rather flat reading of "Shadow Waltz" that sounds like a leftover from Roach's Jazz in ¾ Time album. These aren't Sonny's most compelling performances and they have little relationship with side A, so the album as a whole, despite the often brilliant playing by all concerned, seems patched together rather than a thought-through statement of intent. Still, it's post 1954, pre-bridge Sonny, and therefore not to be missed. If you don't want to risk the vagaries and expense of sourcing a clean original copy, VMP's edition may be the best bang for your buck—if you can still find a copy floating around at this juncture.

After leaving Prestige Records (a step many great jazz musicians took with considerable relief), Rollins recorded for several labels before his bridge sabbatical, stopping at Blue Note and Verve as well as Riverside Records. Most surprising, perhaps, was his work for west coast label Contemporary Records, whose stable of players like Art Pepper, Lennie Niehaus, and the Lighthouse All Stars were far removed from Rollins' muscular and bluntly humorous bebop stylings. Rollins ended up recording two albums for the label (Levy notes that he signed an agreement to cut three but for whatever reason did not complete the set.) Now Craft Recordings have boxed those two albums along with a disc of session outtakes under the rubric Go West! The Contemporary Record Albums. The box comprises Way Out West, Sonny Rollins and the Contemporary Leaders, and an outtakes disc, with the two main selections all-analogue pressings and the outtakes including a digital step.

After leaving Prestige Records (a step many great jazz musicians took with considerable relief), Rollins recorded for several labels before his bridge sabbatical, stopping at Blue Note and Verve as well as Riverside Records. Most surprising, perhaps, was his work for west coast label Contemporary Records, whose stable of players like Art Pepper, Lennie Niehaus, and the Lighthouse All Stars were far removed from Rollins' muscular and bluntly humorous bebop stylings. Rollins ended up recording two albums for the label (Levy notes that he signed an agreement to cut three but for whatever reason did not complete the set.) Now Craft Recordings have boxed those two albums along with a disc of session outtakes under the rubric Go West! The Contemporary Record Albums. The box comprises Way Out West, Sonny Rollins and the Contemporary Leaders, and an outtakes disc, with the two main selections all-analogue pressings and the outtakes including a digital step. The star is, of course, Way Out West, a trio album Sonny cut with drummer Shelly Manne and bassist Ray Brown. This album, recorded in 1957, is another example of Rollins working with musicians who had strong enough personalities not to be utterly overshadowed by him. Brown was one of the best mainstream bassists in the business and Manne was a brilliant, subtle, and tasteful drummer noted for his sense of humor. Way Out West, unlike Freedom Suite, is a perfectly balanced forty minutes of music, with six songs total, two with explicit Western themes, two Rollins originals and two top-shelf ballads. Manne never dominates the proceedings but makes his indelible mark with intros to the Western songs and the whole thing comes off as, well, practically perfect in every way. This album has been prized for its sonics for decades and has been reissued a dizzying number of times. The Contemporary box pressing is very good, if not awe inspiring. No promises it is the absolute best out there but it should be more than adequate for most listeners.

With the Contemporary Leaders (1959) throws Sonny in with several musicians who recorded for the label: Manne again, Hampton Hawes, Barney Kessel, Leroy Vinnegar, with Victor Feldman guesting on vibes on one track. The results are mixed and the song selection has been described by pens wiser than mine as "perverse." When an album starts with "I've Told Ev'ry Little Star" in an arrangement that may cause early male-pattern baldness, and follows it up with "Rock-a-bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody," the listener may suspect a joke is being had at his or her expense. There is a great Rollins on this record—how could there not be given the provenance?—but the chemistry isn't there. It would be the last studio album he cut before his bridge sabbatical. The value proposition of the Craft box depends, naturally, on the price point. At MSRP of $125, justifying the purchase seems difficult, more so as Craft will be releasing Way Out West individually towards the end of 2024. At $80 (where it can be found at some online relators), you can argue you are getting two AAA Rollins discs for $30 each (roughly the going rate), another outtakes disc for $20, a booklet, and an attractive, useless box to hold them all into the bargain. Way Out West" in whatever format you choose, is not to be missed; Contemporary Leaders is more than a curiosity on a label that rarely gets its just desserts.

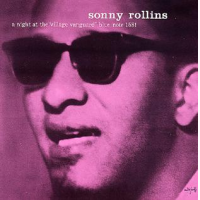

A Night at the Village Vanguard, a live trio album notable for being the first live jazz album recorded at the venue and also for being just plain awesome, has, like Way Out West, gone through various issues. It was first released as a single disc. The Japanese later issued two discs of outtakes (as did American Blue Note on a tan double-LP). In the digital era, the company combined the sessions on two CDs.

A Night at the Village Vanguard, a live trio album notable for being the first live jazz album recorded at the venue and also for being just plain awesome, has, like Way Out West, gone through various issues. It was first released as a single disc. The Japanese later issued two discs of outtakes (as did American Blue Note on a tan double-LP). In the digital era, the company combined the sessions on two CDs. Blue Note has now returned to the well with their Tone Poet issue of the whole shebang on three LPs, with the original session on LP 1 and the remaining tracks on 2 & 3. The discs are packaged in heavyweight cardboard sleeves hinged at the edge, with a booklet that includes an interview with Sonny and background details on the session from Levy. It is delightful to hold and blessedly space-efficient. The set is being toted as the first "complete on LP" issue of the Vanguard material all in one place, but its real claim to fame is the use of the 7-inch reels from the on-location tape machine instead of later dubbed reels. Blue Note claims that using the original tapes (long ignored in the vaults due to the format) results in one less step of sonic losses, and also notes that the tapes were in great shape since they had barely been played. What vinyl lovers are getting, then, is a full set of the music in best-ever sonics for a quite reasonable price ($70 for three discs, when the Tone Poet MSRP for one-disc issues hovers around $38).

On this reviewer's decent but hardly cutting-edge rig (reader, I regret to inform you that my turntable cost less than my car—or my house) the sound certainly runs rings around the old double CD issue and offers depths beyond the Blue Note tan twofer (I have not heard original issues or the Japanese pressing of alternate tracks). If you collect vinyl, this edition comes highly recommended. The music, as always, remains fabulous, especially given the seat-of-the-pants circumstances surrounding it. Rollins, according to Levy, first assembled a quintet for the gig, then fired every single one of them. Then, after sampling Pete La Roca and Donald Bailey during an afternoon session, he fired them and pulled in Elvin Jones and Wilbur Ware as last-minute replacements. (One cut from the afternoon session made the original album; another was included in the remaining issued tracks.)

The set draws heavily on well-known standards because there had been no rehearsals, with Sonny apparently announcing the tune to his bandmates and then diving into performance immediately. His improvisations are plunging, puckish, virtuosic... in short, era-defining and majestic. And all were scraped from the very edge of his teeth. Humor is never far away, both in the playing and in the playful spoken introductions to tunes that Blue Note includes on this issue (brevity is the sole of wit and the introductions are too brief to bore the listener with repetition). Is the playing "perfect"? Hardly, especially on the tracks included on discs 2 & 3.

Sometimes the whole enterprise seems in danger of veering off a cliff. Still, they are unmissable and delightful. Blue Note, in their "I have seen the analogue light!" era, had been oddly hesitant to exploit the six discs of Rollins material in their vaults. A Night at the Village Vanguard rolled out several years deep in the program, along with a Blue Note "Classics" issue of Newk's Time that, in my pressing at least, was botched. No sightings of Sonny Rollins Volume 1 or 2 have yet been confirmed. The label's six-disc extravaganza of Ornette Coleman material (from a period in that saxophonist's career that has been generally undervalued) doesn't appear to have been vacating shelves very rapidly, and it's hard to understand why Sonny's six Blue Note discs were not picked for that luxury treatment instead. But the live Village material is easily the best he did for the label and it's good to see it in such a painstaking issue.

The only thing trendier than an all-analog reissue might just be a Record Store Day special, and Sonny received one this year in the form of Freedom Weaver, a collection of air shots from his European tour of 1959 that took place just before the bridge sabbatical. These performances have been available on bootlegs for years, but Resonance Records, one of the indefatigable Zev Feldman's many labels, has now issued a cleaned-up version of the recordings with proper clearances. At last, royalties from this long-treasured music will make their way to Sonny himself. Like the Vanguard set, Freedom Weaver comes with a booklet that includes commentary from the great man himself. Rollins toured with a trio, with Henry Grimes playing bass on all the performances and Pete LaRoca, Joe Harris, and Kenny Clarke rotating in the drum chair. Rollins notes that the absence of a piano gave him more harmonic freedom when improvising, and it probably helped the economics of touring as well. Rollins apparently was dissatisfied with these performances in earlier years, and as Levy makes clear, was sometimes so dissatisfied with his fellow musicians on the tour that things came to blows.

The only thing trendier than an all-analog reissue might just be a Record Store Day special, and Sonny received one this year in the form of Freedom Weaver, a collection of air shots from his European tour of 1959 that took place just before the bridge sabbatical. These performances have been available on bootlegs for years, but Resonance Records, one of the indefatigable Zev Feldman's many labels, has now issued a cleaned-up version of the recordings with proper clearances. At last, royalties from this long-treasured music will make their way to Sonny himself. Like the Vanguard set, Freedom Weaver comes with a booklet that includes commentary from the great man himself. Rollins toured with a trio, with Henry Grimes playing bass on all the performances and Pete LaRoca, Joe Harris, and Kenny Clarke rotating in the drum chair. Rollins notes that the absence of a piano gave him more harmonic freedom when improvising, and it probably helped the economics of touring as well. Rollins apparently was dissatisfied with these performances in earlier years, and as Levy makes clear, was sometimes so dissatisfied with his fellow musicians on the tour that things came to blows. He has now mellowed a bit, which of course was necessary if an authorized edition was to appear during his lifetime. This assembly of fairly-short concerts recorded in a short span of time means that tunes are repeated. The one repeated the most times, unfortunately, is "I've Told Every Little Star," a tune that does not endear itself with repetition. Sound quality of the concerts is variable. It is mostly very good to quite acceptable, with the exception being a German concert that appears to have been recorded on a submerged and leaky submarine. The set ends with three fifteen-minute performances by Rollins featuring Kenny Clarke and these, thankfully, are in good fettle. Even more than the Vanguard performances, these air shots prepare us for the next phases of Rollins' career, when he sometime takes out a tune for twenty-minutes or more, testing the endurance of both bandmates and audience.

All in all, Freedom Weaver is prime Rollins in mostly good sound, showing why he was a preeminent improviser of the 1950s. Resonance has released the set on four LPs or three CDs. The tracks, to this reviewer's knowledge, are not all-analog, so format choice comes down to one's financial resources, available equipment, and media preferences. The LP version I received was quiet, flat, and well-centered and sounded just fine, but you may well chose to stream this one or collect it on compact disc. My copy was also steeply discounted from MSRP, which is the only way I personally could justify picking it up on vinyl. Regardless of format, it's good to have this excellent music out in legitimate form. Compared to my old CD bootleg version (forgive me, Sonny) the sound is marginally better but not revelatory. But if you want to own a copy, there is no reason not to plump for the Resonance issue.

If Freedom Weaver has a lesson for the Rollins fan, it seems to match that of the Vanguard material. Perfection is not to be found here—just the joy and exhilaration of brilliant musicians reacting to one another intuitively and solving the music problems they set for one another—and sometimes stumble across—in real time. There are fluffed notes and crossed wires from time to time. Mistakes are made. But this is jazz of the highest caliber and not to be missed.

Long live Sonny Rollins.

Tags

Highly Opinionated

Sonny Rollins

Patrick Burnette

Coleman Hawkins

Lester Young

Charlie Parker

duke ellington

John Coltrane

Sonny Stitt

Miles Davis

Max Roach

Oscar Pettiford

Harold Land

Clifford Brown

Art Pepper

Lennie Niehaus

Lighthouse All Stars

Shelly Manne

Ray Brown

Hampton Hawes

Barney Kessel

Leroy Vinnegar

Victor Feldman

Pete LaRoca

Donald Bailey

Elvin Jones

WIlbur Ware

Ornette Coleman

Henry Grimes

Joe Harris

Kenny Clarke

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.