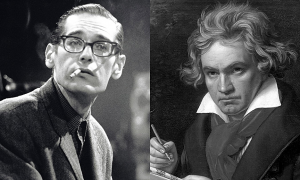

Home » Jazz Articles » The Blue Note Portal » Claude Debussy on So What

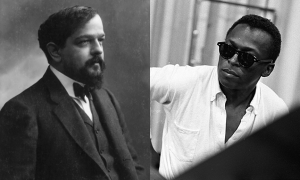

Claude Debussy on So What

Claude Debussy (from his dairy) to his sister, Adèle-Clémentine Debussy, after some mysterious temporal anomaly, 1910 (or perhaps 1959?).

My Dearest Adèle,

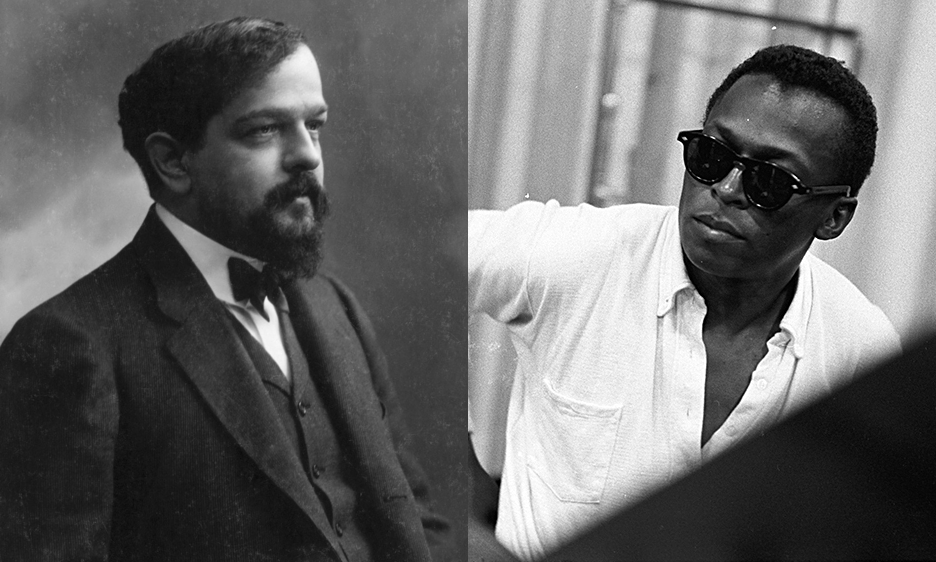

I write to you in a state of profound astonishment, having experienced a phenomenon so extraordinary that I scarce know how to frame it within the language of our own musical world. By some inexplicable quirk of fate, I have been transported to a future time, to the year 1959 in America, where I have encountered a piece of music titled "So What" by a composer and trumpeter named Miles Davis. This encounter has left me both unsettled and inspired, and I must share my impressions with you, knowing your keen ear for the subtleties of sound.

This "So What" belongs to a genre they call "jazz," a music so far removed from our salons and concert halls that it seems to originate from another sphere entirely. It begins with a sparse, almost ethereal interplay between a double bass and a piano, creating a tonal landscape that is at once minimal and evocative. The harmony is not bound by the traditional progressions of our tonal system but rests upon a mere two chords, oscillating in a manner that feels like the gentle ebb and flow of a dream. It reminds me, in some strange way, of my own attempts to capture the fluidity of nature in works like La Mer, yet here the effect is rawer, less polished, as if the music itself is breathing.

Then enters the trumpet of Miles Davis, a sound so piercing yet so laden with nuance that it seems to paint emotions directly onto the air. His melody—if one can call it that—is deceptively simple, a series of notes that float above the harmonic foundation with a cool, almost detached elegance. Yet beneath this surface lies a depth of feeling, a melancholic undercurrent that speaks to something universal, something beyond the constraints of form or convention. I found myself thinking of my own Clair de Lune, of how I sought to evoke mood over structure, but this "So What" takes such an idea to an entirely new realm.

What struck me most, Adèle, was the manner in which this music unfolds. It is not composed in the way we understand, with every note meticulously notated and every phrase predetermined. Instead, the musicians engage in what they call "improvisation," a spontaneous creation of melody and rhythm in the very moment of performance. Each player—whether on trumpet, saxophone, or piano—takes their turn to weave variations upon the central theme, guided not by a score but by instinct and mutual understanding. This freedom is both exhilarating and disorienting to me, accustomed as I am to crafting every harmonic shift with deliberate intent. Yet I cannot deny the beauty in this liberation, the sense of music as a living, breathing entity.

I must confess that at first, I struggled to grasp the logic of "So What." Where is the development, the thematic transformation, the resolution that anchors our compositions? But as I listened, I began to perceive a different kind of coherence, one rooted not in narrative or architecture but in atmosphere and emotion. This jazz seems to exist in the present moment, unburdened by the past or future, much like the impression of a fleeting cloud or the shimmer of light on water. It resonates with my own desire to break free from the rigidity of classical forms, to let sound suggest rather than dictate.

The instruments themselves are a revelation. The saxophone, an instrument I have only vaguely encountered, produces a tone that is both sensual and wild, like a voice from the untamed edges of the human spirit. The drums, far from mere timekeepers, ripple and pulse with a rhythmic complexity that defies the steady meters of our waltzes or mazurkas—they seem to mimic the irregular heartbeat of life itself. And Miles Davis's trumpet, with its muted cries and bold assertions, carries a timbre that is at once intimate and distant, as though it speaks from the depths of a personal reverie.

I cannot help but wonder what this music portends for the future of our art. In my own time, I have sought to redefine harmony and form, to draw inspiration from the East and from nature itself, as in Pagodes or Nuages. Yet here, in 1959, I see a music that has cast aside even more of the old rules, embracing a rawness and immediacy that both challenges and captivates me. Might I, in my own compositions, dare to incorporate such spontaneity, such a focus on pure sonority over structure? I long to experiment with these ideas, to see if I might capture even a fragment of the spirit of "So What" in my own tonal palette.

Adèle, I wish I could bring this music back to Paris, to play it for you through some miraculous device of this future age. I imagine you would find in it the same poetic ambiguity that I strive for in my own work. For now, I must content myself with these words, knowing that soon I shall return to our own era, where such sounds remain but a dream. Yet I carry with me a renewed sense of possibility, a reminder that music, like the sea or the sky, knows no bounds.

Until we meet again, I remain your affectionate brother, ever seeking the ineffable in sound.

Yours,

Claude

P.S. Should you ever hear tales of a Miles Davis or his "So What," know that you are encountering a visionary whose music whispers of moods and impressions beyond our imagining. I shall never forget the spell it cast upon me.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.