Home » Jazz Articles » So You Don't Like Jazz » The Unlikely Story of Cannonball Adderley's Rise to the Top

The Unlikely Story of Cannonball Adderley's Rise to the Top

Courtesy Mosaic Images

The Foundation of a Giant

Why is Cannonball's story my favorite? Because it is the ultimate musician's fantasy, but with a twist. His "discovery" was not about unearthing raw potential; it is actually about a fully-formed master, hiding in plain sight, who was finally put to the test by fire, and did not just survive—he thrived. To understand the magic of that night, you first have to understand the man. Julian Adderley's path was guided by his parents' emphasis on excellence and high expectations. His grandfather was an immigrant tailor and musician from the Bahamas. His parents were respected educators at Florida A&M University (FAMU), where his father, a jazz cornetist, was a member of the legendary Marching 100. The band's motto speaks volumes: "Highest quality of character, achievement in academics... perfection in musicianship..." Julian's musical development was swift and serious.By age twelve, he and his brother Nat Adderley had already formed their first band. It was their drummer who, thanks to Julian's ravenous appetite, gave him the nickname "Cannibal." Over time, as people misheard the word, it evolved into the more familiar "Cannonball." His path was one of continuous exploration; he switched from trumpet to saxophone in 1942, finally finding his true voice. His prodigious drive was reflected in his education. He finished high school at just 15 and immediately enrolled at FAMU, where the Adderley brothers played in the college band alongside a gifted young blind pianist named Ray Robinson—soon to be known as Ray Charles. Cannonball graduated with his music degree just shy of his 18th birthday. Yet, despite all this talent, a full-time music career was not the assumed path. His father, recalling his own experience of being stranded on the road in Tennessee and forced to work the fields to earn his way home, discouraged his sons from the risky life of a professional musician. Following a couple of years touring with regional bands, Cannonball took this advice to heart. He accepted a job as the band director at Dillard High School in Fort Lauderdale, resigning himself to a respectable life as a teacher.

Then Uncle Sam threw a wrench into his carefully laid plans. Yet even the U.S. Army could not stop his musical growth. Drafted in 1951, he eventually became the leader of the 36th Army Dance Band. After his discharge, he did not rest; he enrolled at the Navy School of Music in Washington, D.C., diligently adding clarinet and flute to his formidable skill set. By 1954, Julian Adderley's path seemed firmly set. The musical world he re-entered was different; the gradual decline of the horn-heavy big bands meant the life of a touring musician was more precarious than ever. So he returned to his quiet, respectable life as the band director at Dillard High School, supplementing his income by playing local gigs and selling cars. He was a secret weapon, seemingly resigned to remaining a secret. But his brother Nat was out there, touring with Lionel Hampton's orchestra, living the life their father had warned them against. And he had a plan.

The Road to Bohemia

Nat was fully aware of the tremendous talent his brother possessed, and eager to let the rest of the world know about it. The first attempt came during Julian's Christmas break from school. Nat convinced him to visit New York, where he made sure Julian crossed paths with the legendary Lionel Hampton. When Hampton learned that the visiting schoolteacher from Florida was an alto player, he invited him to sit in with the band. The performance was so impressive that Hampton immediately offered him a job on the spot. For a moment, it seemed the plan had worked perfectly. But the band's true power behind the curtain was Hampton's wife, Gladys Hampton. Fearing a clique mentality, she had a firm rule against hiring two brothers to work in the same band. The offer was vetoed. Julian, his brush with the big time thwarted, returned to Florida and his teaching job.Then, three months later in March of 1955, the jazz world was shaken to its core. Charlie "Bird" Parker, the titan of the alto saxophone, was dead. The throne was empty, and the New York scene was buzzing with a profound sense of loss and a quiet, nagging question: could anyone possibly follow Bird? It was in this supercharged atmosphere that Nat made his second attempt. That summer, he convinced Julian to drive up to New York again, this time under the practical guise of taking graduate courses for his master's degree. Nat also assured Julian there would likely be opportunities for gigs—the understatement of a lifetime.

Wasting little time after their long drive from Florida, they met up with one of Nat's musician friends and his brother. Their destination was the Café Bohemia in Greenwich Village, where they planned to see trombonist Jimmy Cleveland perform with the house band. Nat, dangling a chance for Julian to do a gig with an R&B singer, made sure Julian brought his saxophone. The small group took a table in the back, two brothers and their friends ready to soak in the sounds of the world's jazz capital, in a city still mourning its fallen king. They had no idea they were about to become the main event.

The Trial by Fire

The Café Bohemia was a new jazz club with a backstory as colorful as its clientele. Originally a strip club, its owner, Jimmy Garofalo, had craftily converted it into a jazz venue after Charlie Parker himself offered to play there to pay off a tab. But Parker's sudden death just a few months earlier meant the club's grand opening never went as planned, leaving it with a great house band but without its star attraction. On this particular night, the audience was growing impatient by a late start and apparent confusion on the bandstand, another reminder of the void Parker had left behind. The bandleader, the formidable bassist Oscar Pettiford, was annoyed and growing angry. His regular saxophonist was a no-show, and the substitute had not arrived either. Scanning the room for a solution, Pettiford's eyes landed on a familiar face: saxophonist Charlie Rouse. He caught his attention and motioned him to come up to the bandstand, asking him to fill in and get him out of a jam. Rouse demurred with the excuse that he did not have his horn. Pettiford's frustration grew.His gaze swept the room again and stopped on the unmistakable shape of a saxophone case at a table in the back. Undeterred, he told Rouse to borrow a horn from the big guy in the back. This is the moment the story pivots from a simple delay into jazz mythology. Rouse walked toward the back of the club, but when he saw the man holding the horn case, he recognized him from a gig they had played together down in Florida. An impish, mischievous idea sparked. Here was an opportunity for a cruel but classic musician's prank: setting up the unsuspecting music teacher from the sticks for public humiliation in front of New York's toughest players. It would be hilarious. Instead of asking to borrow the saxophone, Rouse leaned in and told Julian Adderley that Oscar Pettiford wanted him to sit in. He then returned to Pettiford, telling him the man would not lend his horn, but was willing to sit in himself.

A moment later, the New York crowd watched as a smiling, unknown, "jolly giant" of a man made his way to the stage—understandably nervous by the sudden turn of events, but happy to oblige. Pettiford, unaware of Rouse's prank, was incensed by this yokel's gall and naïveté. He decided to teach this out-of-town amateur a lesson he would never forget. He turned to the band and called one of the most notoriously difficult tunes in the bebop repertoire, the chord-heavy "I'll Remember April," at a blistering tempo designed to chase this pretender back to where he belonged. The prank backfired spectacularly. Cannonball did not just keep up; he took flight. He leaned into his horn and unleashed a cascading river of liquid fire, a torrent of sophisticated ideas executed with breathtaking power and joyous precision. The band was floored. The rhythm section, expecting to support a fumbling amateur, suddenly found themselves in a high-level conversation with a master. The audience was electrified. By the end of his first stunning solo, the prank was over. Smirks were replaced by awe, and Julian remained for the rest of the set.

The club owner, Jimmy Garofalo, realizing he had just witnessed something extraordinary, rushed over to Nat Adderley's table. "Who is that guy?" he demanded. Nat, thinking he might be a union rep, played it cool and feigned ignorance. "I don't know his name," he said, "but I think he is from Florida. Back home, they call him Cannonball." With that one word—a childhood nickname born of a ravenous appetite—the legend was christened. Julian "Cannonball" Adderley had arrived.

The Legend and the Aftermath

Of course, a story this perfect has been polished through decades of telling and retelling. Jazz academics have rightly pointed out inconsistencies in the various accounts, and one cannot discount the possibility of some savvy public relations at play. Legends, after all, have a way of growing with time. But to get bogged down in a forensic analysis would be to miss the point entirely. This is the story that electrified the jazz world. It is the classic tale that has captivated musicians and fans for over half a century because it captures the essence of a seismic event. And the proof of that event is not in the story, but in what happened next. The professional fallout from that night at the Café Bohemia was immediate and undeniable. The buzz was so intense that record labels scrambled to sign the unknown teacher from Florida. Within a matter of weeks, the industry whirlwind began: On July 14th, just a few weeks after the gig, he was in the studio for Savoy Records, cutting the tracks that would become his debut, Presenting Cannonball Adderley, as well as the album Discoveries. By July 21st, he had already signed a new deal with the major label Emarcy and was back in the studio for his self-titled album, a session that continued through August. The whirlwind culminated in late October when Emarcy, betting heavily on their new star, put him in the studio with a full string section for the prestigious album Adderley and Strings.

This is the story that electrified the jazz world. It is the classic tale that has captivated musicians and fans for over half a century because it captures the essence of a seismic event. And the proof of that event is not in the story, but in what happened next. The professional fallout from that night at the Café Bohemia was immediate and undeniable. The buzz was so intense that record labels scrambled to sign the unknown teacher from Florida. Within a matter of weeks, the industry whirlwind began: On July 14th, just a few weeks after the gig, he was in the studio for Savoy Records, cutting the tracks that would become his debut, Presenting Cannonball Adderley, as well as the album Discoveries. By July 21st, he had already signed a new deal with the major label Emarcy and was back in the studio for his self-titled album, a session that continued through August. The whirlwind culminated in late October when Emarcy, betting heavily on their new star, put him in the studio with a full string section for the prestigious album Adderley and Strings. This meteoric rise, however, came with a heavy price. In a city still mourning Charlie Parker, the timing was perfect for a marketing narrative. The press and record labels, eager to fill the void, quickly crowned him "The New Bird." This was both a blessing and a curse. The comparison generated incredible intrigue and drew massive attention. But it also, understandably, turned off critics and many of Parker's loyal followers who saw it as a shameless commercial ploy so soon after Parker's death. This was not Julian's doing; it was the work of commercial interests looking to capitalize on a moment. Yet it was Cannonball who had to stand on stage every night under the weight of that impossible comparison. As many have noted, being hailed as the "next" anything—the next Sinatra, the next Elvis, the next Beatles—rarely works out well for the artist who has to carry that burden.

The Power of Contrast

The "New Bird" hype and flurry of recordings did not guarantee a career. By late 1957, the quintet Cannonball co-led with his brother Nat had been forced to break up due to financial pressures. Adderley, however, remained a presence on the New York scene, taking gigs where he could. His future course was again set at the Café Bohemia—the very site of his explosive debut. Both he and Miles Davis were at the club. In a conversation, Adderley mentioned he was considering an offer to join Dizzy Gillespie's big band. Miles, ever direct, made a counteroffer: "Why don't you join my band?" When Cannonball joined, and John Coltrane returned, the legendary Miles Davis Sextet was born.This period became arguably the most transformative experience of his career. The lessons began immediately. The schoolteacher in Cannonball, a man with a formal music degree, initially resisted instruction. When Miles attempted to pass on some musical insights about chords, Cannonball did not engage—he later admitted he was a bit arrogant at that time. The wake-up call came when he read an interview in which Miles, while praising his ability to swing, bluntly stated that he "did not know much about chords." After that, Cannonball began to truly listen. He learned from Miles that power was not about the number of notes you played, but which ones you chose. In an era of non-stop virtuosity, Miles' genius was his innovative use of space. It was a deep lesson in musical economy that reshaped Adderley's entire approach, transforming his solos from breathless runs into more thoughtfully structured, lyrical statements.

His other teacher was the man standing next to him on the bandstand every night: John Coltrane. The two saxophonists were perfect foils. Miles, the master alchemist, would play them against each other to fuel their growth, whispering to Coltrane to "learn how to edit" from Cannonball's lyricism, then turning to Cannonball and telling him to absorb Coltrane's "harmonic thinking." The result was an extraordinary musical dialogue. In this "laboratory," as Cannonball called it, the two saxophonists pushed each other to such heights that their sounds would sometimes merge into one continuous, fluid thought. Cannonball emerged from this experience in 1959 a more complete and nuanced artist, having learned that less is sometimes more. He had learned how to lead a band by watching Miles subtly change its style. But importantly, he also learned what not to do by observing Miles. He consciously rejected Miles's famously aloof stage persona. Adderley took issue with what he saw as disrespect towards the audience. He had absorbed Miles's musical lessons, but he would forge his own path as a leader: remaining a warm, engaging educator and entertainer, bringing the joyous gospel of jazz directly to the people.

A Masterpiece in Blue

In the late summer of 1959, the Miles Davis Sextet released its final studio album. Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959) was a critical and commercial success by the standards of the day, selling a respectable 50,000 copies in its first year. But no one could have predicted its future. Over the following decades, it quietly grew into a cultural phenomenon, a multi-platinum behemoth that is now widely regarded as the greatest and most influential jazz album of all time. While it stands as a monument to the genius of Miles Davis, its magic lies in the collective alchemy of the entire sextet. The lineup itself is a roll call of legends: John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, Jimmy Cobb on drums, and, of course, Julian "Cannonball" Adderley on alto saxophone.

In the late summer of 1959, the Miles Davis Sextet released its final studio album. Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959) was a critical and commercial success by the standards of the day, selling a respectable 50,000 copies in its first year. But no one could have predicted its future. Over the following decades, it quietly grew into a cultural phenomenon, a multi-platinum behemoth that is now widely regarded as the greatest and most influential jazz album of all time. While it stands as a monument to the genius of Miles Davis, its magic lies in the collective alchemy of the entire sextet. The lineup itself is a roll call of legends: John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, Jimmy Cobb on drums, and, of course, Julian "Cannonball" Adderley on alto saxophone. Listening to its sublime, almost architectural beauty, one might imagine weeks of intensive rehearsal. The truth is even more staggering. The musicians arrived at the studio with almost no preparation, working from basic modal sketches Davis often provided just moments before the tape rolled. Most tracks were stunning first takes. It is a testament not to perfection, but to empathy; a vulnerable, spontaneous conversation between masters captured in real time. Its influence soon spilled far beyond the confines of jazz. In the decades that followed, a generation of rock visionaries discovered its deep, meditative space and cited it as a profound influence. The list includes guitarists such as: Duane Allman, Carlos Santana, David Gilmour, and Jerry Garcia, as well as innovators like The Doors, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, and Brian Eno.

Why does this album endure so profoundly? It was a perfect storm. It arrived at a precise moment in American culture, offering a cool alternative to the frantic energy of both bebop and early rock and roll. Critically, it captured this specific group of musicians at the perfect intersection of their careers: Coltrane on the verge of his own spiritual explorations, Evans with his classical touch, and Cannonball providing the essential, blues-drenched soul that anchors the entire project in human warmth. All of this converged to create something more than a masterpiece. It created perhaps the most welcoming and effective tool ever made for turning a curious listener into a lifelong jazz fan.

Something Else Entirely

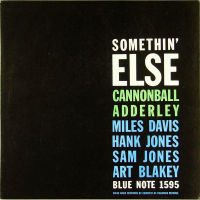

For the rock fan who discovers jazz through the portal of Kind of Blue, the journey often leads to a second, breathtaking discovery. Stumbling upon Cannonball Adderley's 1958 album Somethin' Else (Bluenote, 1958) feels like finding a secret, forgotten chapter—a Christmas present in July. It possesses the same cool, spacious, and deeply melodic atmosphere, and played back-to-back, the two albums feel like two sides of the same coin, a seamless double-album experience for the uninitiated. The astonishing reality is that this album was not a follow-up; it was a prophecy. Recorded for the Blue Note label in March 1958, a full year before the Kind of Blue sessions, it serves as a stunning precursor to the masterpiece that would follow. The project was Cannonball's date as a leader, but the personnel list is what makes it legendary. The band assembled was a murderer's row of talent: the elegant Hank Jones on piano, the rock-solid Sam Jones on bass, and the explosive, polyrhythmic engine of Art Blakey on drums. And on trumpet, in a generous act of mentorship and respect, was Miles Davis himself.

For the rock fan who discovers jazz through the portal of Kind of Blue, the journey often leads to a second, breathtaking discovery. Stumbling upon Cannonball Adderley's 1958 album Somethin' Else (Bluenote, 1958) feels like finding a secret, forgotten chapter—a Christmas present in July. It possesses the same cool, spacious, and deeply melodic atmosphere, and played back-to-back, the two albums feel like two sides of the same coin, a seamless double-album experience for the uninitiated. The astonishing reality is that this album was not a follow-up; it was a prophecy. Recorded for the Blue Note label in March 1958, a full year before the Kind of Blue sessions, it serves as a stunning precursor to the masterpiece that would follow. The project was Cannonball's date as a leader, but the personnel list is what makes it legendary. The band assembled was a murderer's row of talent: the elegant Hank Jones on piano, the rock-solid Sam Jones on bass, and the explosive, polyrhythmic engine of Art Blakey on drums. And on trumpet, in a generous act of mentorship and respect, was Miles Davis himself. This album marks the very last time Miles Davis would ever record as a sideman on another musician's project. Because it was Cannonball's session on his label for the day, Miles could not be credited as the leader, yet his fingerprints are all over the music. He reportedly had a heavy hand in the studio, helping to shape the arrangements and the minimalist, lyrical mood. The iconic title track, with its famous, haunting intro from Miles, sets a tone that is unmistakably a blueprint for the modal explorations to come. Somethin' Else is more than just a classic album; it is a testament to the unique alchemy between two giants. It captures Miles nurturing the very qualities in Cannonball—the soulful lyricism, the deep connection to the blues—that he needed to perfect his own vision. It is the sound of a master passing the torch, even as he was still carrying it himself.

The Chicago Detour

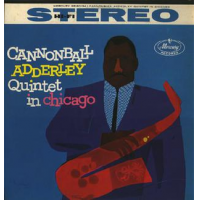

The story of Cannonball Adderley's tenure with Miles Davis has one final, fascinating footnote: a rare glimpse of the world's greatest sextet without its leader. Recorded in Chicago in February 1959, just before the Kind of Blue sessions, the album Cannonball Adderley Quintet in Chicago (Mercury, 1958) captures what happened when the sidemen were left to their own devices. For the listener, it is a revelation. With Miles absent, at times the handbrake comes off. The band puts the gas pedal down, trading the cool, contemplative mood of their other work for a more fiery and freewheeling energy. It is an opportunity to hear the raw, dynamic interplay between Adderley and Coltrane, unleashed and unfiltered. The album is pure, uncut fun, showcasing their distinct personalities and their near-telepathic connection. The session was an impromptu affair, reportedly co-led by Adderley and Coltrane. However, Adderley's label, Mercury, released the album without crediting Coltrane as a co-leader. In a fascinating twist of fate that mirrors his session with Miles, this album marked John Coltrane's final recorded appearance as a sideman. Cannonball Adderley, the humble schoolteacher from Florida, now holds the unique distinction of having led both Miles Davis and John Coltrane on their very last gigs as sidemen. It was the end of his apprenticeship. The masterclass was over, and he was more than ready to step out on his own.

The story of Cannonball Adderley's tenure with Miles Davis has one final, fascinating footnote: a rare glimpse of the world's greatest sextet without its leader. Recorded in Chicago in February 1959, just before the Kind of Blue sessions, the album Cannonball Adderley Quintet in Chicago (Mercury, 1958) captures what happened when the sidemen were left to their own devices. For the listener, it is a revelation. With Miles absent, at times the handbrake comes off. The band puts the gas pedal down, trading the cool, contemplative mood of their other work for a more fiery and freewheeling energy. It is an opportunity to hear the raw, dynamic interplay between Adderley and Coltrane, unleashed and unfiltered. The album is pure, uncut fun, showcasing their distinct personalities and their near-telepathic connection. The session was an impromptu affair, reportedly co-led by Adderley and Coltrane. However, Adderley's label, Mercury, released the album without crediting Coltrane as a co-leader. In a fascinating twist of fate that mirrors his session with Miles, this album marked John Coltrane's final recorded appearance as a sideman. Cannonball Adderley, the humble schoolteacher from Florida, now holds the unique distinction of having led both Miles Davis and John Coltrane on their very last gigs as sidemen. It was the end of his apprenticeship. The masterclass was over, and he was more than ready to step out on his own. Conclusion: The Magic and the Method

So, how do you turn someone on to jazz? In a column dedicated to that very question, the answer often begins with one album and a compelling story. The album, this time, is Kind of Blue. One look at the comments on a YouTube stream with over 14 million views shows why it remains the ultimate gateway. For every seasoned pro leaving a comment like, "My guitar teacher told me Miles' solo on this was everything a jazz solo should be... 40 years later, I agree," there is a newcomer confessing, "I am a metal head but jazz is my rest moment. Love it and respect it." It is the genre's great unifier, the common ground where all listeners can meet. As one fan perfectly summarized, "I can dig as deep into the rarest and most obscure jazz as I have done all my life, but in the end, all roads lead here." But music is only half of the equation. The secret weapon is the story of the man whose warm, blues-drenched sax appeal provides the album with so much of its soul. The story of Julian "Cannonball" Adderley—the brilliant young schoolteacher from Florida who, against all odds, walked into the lion's den of New York jazz and emerged a legend—is utterly compelling. The suggestion, then, is simple. Share the magic. Start with the universal appeal of Kind of Blue. Then share the story of Cannonball: how he got his name, how he survived his trial by fire, and how he stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the giants. This article only covers the beginning of his journey. When your newcomer is ready for the next step, Cannonball's own brilliant quintet is waiting. It is another open door, a path that leads to the mesmerizing, label-defying sounds of other incredible talents he championed, such as Yusef Lateef and Joe Zawinul. You will not just be sharing an album; you will be sharing a story. And in doing so, you might just open a door to a whole universe of sound.Sources:

- Ginell, Cary. "Walk Tall: The Music and Life of Julian 'Cannonball' Adderley." Hal Leonard Corporation, 2013.

- Jones, Ryan Patrick. "'You Know What I Mean?' The Pedagogical Canon of 'Cannonball' Adderley." Current Musicology, nos. 79 & 80, 2005, pp. 169-205.

Tags

So You Don't Like Jazz

Cannonball Adderley

Alan Bryson

Billie Holiday

John Hammond

Ella Fitzgerald

Chick Webb

Edwards Sisters

Chet Baker

Gerry Mulligan

Julian "Cannonball" Adderley

Nat Adderley

Ray Robinson

Ray Charles

Lionel Hampton

Gladys Hampton

Charlie "Bird" Parker

Jimmy Cleveland

Jimmy Garofalo

Oscar Pettiford

Charlie Rouse

Miles Davis

Dizzy Gillespie

John Coltrane

Bill Evans

Wynton Kelly

Paul Chambers

Jimmy Cobb

Duane Allman

Carlos Santana

David Gilmour

Jerry Garcia

The Doors

Stevie Wonder

Marvin Gaye

Brian Eno

Hank Jones

Sam Jones

Art Blakey

Yusef Lateef

Joe Zawinul

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.