Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Dominic Duval: Follow Your Melody

Dominic Duval: Follow Your Melody

Nightbird Inventions

Nightbird Inventions AAJ: How does an artist of your scale seem to emerge out of nowhere, only 15-20 years ago?

DD: The records have to be at the beginning. Without having a product to represent your music, it is very difficult to get work. One year I sent out 50 demo tapes, and got back 52 rejections. One guy hated my music so much that he felt he needed to reject it twice. These recordings are like keys to a door, which opens up other doors for you. I can't stress that enough, about being able to look back at the things you've done on record and being proud of them, and thinking that you've done something worthwhile. It just took me a long time to do that. And you asked me that question—"Why it took me so long to record?"—that's probably why. I didn't do a lot of recording when I was younger because I just didn't think I had enough to say. I hadn't yet created music I wanted or needed anyone else to hear.

AAJ: You started when you realized that you were ready.

DD: Honestly, that's exactly what happened. One day I woke up and I said to myself, "I have been anonymous way too long." I've always thought this attitude was not serving myself or my music very well. "Maybe I am fooling myself I thought?" I just had to step out onto the scene and show the musical world what I was about... To take my chances and my lumps if need be. I think it's one thing to know what you are doing is important, and believing that you are an important musician/artist. It's another thing to actually have other people, people in the industry that you respect, believe you are just that. Now, you know not everyone will always agree with you, and that's OK, we can work on those that dissent. They're right, as freethinking music fans/ critics; I expected that, to some extent. My advice to myself is to be able to take verbal comments, criticism, good or bad. All criticism is important, even though you may not agree with the content at the time it is written.

Finally, for all you new critics out there: in my music, I offer a whole new way of playing the bass and making music with it. Forget the standard way it's been done for decades—a new twist for you to read about and ponder. I didn't think I had enough to say in my earlier musical development; nothing worth documenting or recording, anyway. I feel this was the direction of my journey, and that's about it.

AAJ: Your solo bass recording Nightbird Inventions was a more than convincing indication that you'd reached the state of artistic maturity. It simply couldn't go unnoticed.

DD: Nightbird was my attempt of taking the bass into a different sonic realm. One of the ways I accomplished this was by using different effects that were uncommon to the ear—and to the bass. A lot of thought and preparation went into that recording—not the actual recording time, but finding new techniques to achieve those effects, to get the right sound out of the instrument. To discover how to produce these new sounds, especially the "nightbird" sound.

AAJ: What really amazes me is that your bass solos are very abstract and melodic at the same time. I think that Nightbird is one of the most outstanding bass solo recordings ever.

DD: It's great that you like it. But let me say this: instruments don't make music. People make music. Their lives, their struggles, their loves, their hates, their prejudices, and their creativity—it's all there. Some people would disagree with that thought, but I think you have to have a basic fundamental understanding of music and be able to play it with reasonable clarity. That ability allows you room to play outside of a form. You have to be able to play inside to go outside, I think? Take John Coltrane for instance, I believe he recorded the Johnny Hartman (Impulse!, 1962) and A Love Supreme (Impulse!, 1965) within months of each other; yet' tThey sound in contradiction to one another, stylistcly speaking, but Coltrane could work in both areas equally and at ease. They are both classics, which I listen too often to this day.

For me, it was never just about the bass. I don't play the bass. I play music. It's about making music with other people or making music by yourself. All music needs to have a theme or anti theme, for it to be complete. I think my solo records have a musical foundation, as well as abstract value—not just random sounds, although that too can be a theme, no theme at all. To work in the abstract is to strip an idea to the core. To squeeze the essence out of the music or idea. That's not me, but the great Bill Dixon, who said that.

The main focus of all instrumentalists, whether they are bass soloists or ensemble players, is the sounds one hears coming from the players. I enjoy many types of music, and they all have that one thing in common—they either make you wanna dance or sing or think of a point in time that is somehow relived. It should, at least, have those qualities. I also think music is the best way for me to achieve a solid artistic presence, between me and the listener. To be able to affect others through my work is my main goal.

Working With Cecil Taylor

Working With Cecil Taylor AAJ: Please tell about your music for String Quartet.

DD: The sSring Quartet happened during my second year with Cecil Taylor. Cecil was doing a series of concerts at the Knitting factory which I was a part of. He handled me a piece of his music and asked to take a look at it. Cecil doesn't write music in the normal way, he has his own language and symbols, which is just his. He once said to me that he needed to develop this new writing technique to better serve his way of playing his compositions. After reading the material for awhile, I think I said: "It looks like you are writing a string quartet here." "Yes that's right," he answered, adding "Do you think you can put together a string quartet that could play this piece?"

Cecil spoke, at this time, about his idea to have Kronos Quartet do the piece. I think I have a recording on tape of Kronos trying to play his composition. I don't feel Kronos and Cecil Taylor were a marriage made in heaven. He was commissioned by Kronos to write the piece for them, but it didn't work out well.

So he had music already written for strings, for the most part. Cecil was planning to add himself as a fifth instrument, recording a string quintet. This excited me, as you can imagine. I did say I would work on the piece. I started looking for string players that I thought could play this music.

The first one to come was Tomas Ulrich, who just happens to be one of the finest cellists that I have had the pleasure of working with. Jason Kao Hwang was on the scene for a long time. And I knew his music enough to say that he could do a very good job in the violin chair. Ron Lawrence was the third player that I thought was a really fine violist, and knowing he would love the chance to play with Cecil Taylor.

So I brought this quartet with me into the studio. We did a demo, mostly for Cecil to hear. It was to give him an idea of the variations this string ensemble could produce, especially these particular players. After recording the group, I had it on tape in my car. I drove home from one of the gigs that we did at the Iridium, which was recorded and released [Qu'a Yuba (Cadence, 2000)]. One night during those performances, I drove Cecil home because he was tired.

On the way home I remember saying, "You know Cecil, I did this recording of your string quartet, I would like you to hear it. Let me know what you think of the group for this idea of yours," and so I played it. The first time, after five minutes, he stopped me saying, "Please tell me how you did this?" I said, "I did it with some fundamental ideas of string quartets. I just went from there, improvising." "That's amazing," he said. He asked me to play the whole thing again. It was maybe 30 minutes long. So we sat in front of his house and listened to the whole recording.

"That's the most beautiful thing I've ever heard," was Cecil's reply. It was such honor to hear that from him. "OK, I'll start working on the string quartet tomorrow and let you guys do it," I said. Sadly, he never finished it. And after a couple of months I asked him about the music again. "Cecil<" I said, "I've got this recording, would you mind if I put it out and call the group Cecil Taylor's String Quartet?" His reply was, "No, of course not, go ahead."

I sent it to three or four record companies. Leo Records loved, so he put it out. It was called Navigator, which was a dedication to Cecil Taylor. I used to call Cecil "The Navigator," because no matter how many people were around him, he would be like the lead bird in a flock. He was The Navigator who always knew the way and he got there, musically speaking.

We've done a few records with that group. And that's about all I can say, other than that chamber music has always been one of my favorite to listen to, especially string quartets. I was glad to be able to perform in that particular setting. And making that first record allowed me to do so. I put out a record for CIMP, not so long ago, called Mountain Air (2006), which is a dedication to Cecil's solo record, Air Above Mountains (Enja, 1976)—which is a great record, by the way. A wonderful violinist took Jason's place—Gregory Hubner, a German fellow, excellent.

So, this is the String Quartet story. Navigator was a demo made for Cecil, it was never meant to be released.

Joe McPhee, Jay Rosen, and Trio X

AAJ: One of the biggest subchapters of your recorded musical history is a collaboration with Joe McPhee. How did you meet Joe?

DD: Joe is an easy one. At the time I was working with Mark Whitecage in a trio. We were doing some very nice music. I had heard some of Joe's music in the past somewhere, but wasn't too familiar with most of his earlier works—his early music was more difficult for me to locate. So I didn't have a lot of information on him.

I was recording for CIMP records with Jay Rosen one summer; Bob Rusch had just recorded a duet with Joe and a violinist, called Inside Out (1996). It was done outdoors, with just Joe on soprano saxophone and violinist David Prentice. That evening, Bob played me a track from that recording. I immediately said, "I want to buy it." While driving home, Jay and I started listening to the whole CD. After that we both looked at each other and said, "We need to play with this guy [Joe McPhee]. I called Bob on my cell phone and asked for Joe McPhee's phone number. Both Jay and I wanted to tell him how much we enjoyed his music. So we get Joe's number and call him from my car.

I was recording for CIMP records with Jay Rosen one summer; Bob Rusch had just recorded a duet with Joe and a violinist, called Inside Out (1996). It was done outdoors, with just Joe on soprano saxophone and violinist David Prentice. That evening, Bob played me a track from that recording. I immediately said, "I want to buy it." While driving home, Jay and I started listening to the whole CD. After that we both looked at each other and said, "We need to play with this guy [Joe McPhee]. I called Bob on my cell phone and asked for Joe McPhee's phone number. Both Jay and I wanted to tell him how much we enjoyed his music. So we get Joe's number and call him from my car. I said, "You don't know me, my name is Dominic Duval; I really love your recording with David Prentice. Any time you need a bassist please let me know. He said, "But I don't even have a band." "It doesn't matter," I said, "If you want to do a duet or put together a group. I am there for you."

So, I gave him my phone number, and he did call me. It seems he was asked to do a tribute to John Coltrane at the Knitting Factory. Joe asked me if I know a drummer as well. Of course, I had a great drummer who really liked Joe's stuff [Jay Rosen]. And so we went ahead. We did that concert at the Knitting Factory. And it was the first time we got together. It was sometime in 1998.

Our first record, Rapture (Cadence, 1988), was a Trio X release with the wonderful Rosie Hertline. This happened around the time we did our first concert together, maybe one year later. We played together all of '97, before we actually did the trio record. It was prehistory in the life of Trio X. If you listen to Rapture, it is actually a quartet, with Rosy Hertlein on violin. After that we made The Watermelon Suite (CIMP, 1999), and we've been working as a trio ever since. We are friends. It fits together very well. And the music is very, very special.

Future Plateaus

AAJ: So, is jazz alive?

DD: Well, it is in my life.

AAJ: Many people, including some musicians, are saying it is not.

DD: These are defeated people. If you look at that term jazz—and listen—even the great Joe McPhee will, when speaking about jazz, say jazz is in a box. Music does not have to be that way. Music can be structured and still have that freedom which improvised music has. You just have to be good enough to make it appear that way.

AAJ: That was something I really hoped to hear, thanks. What about future plateaus on your journey?

DD: Well, of course, there's Trio X, which is dear to my heart and a big part of my life. I'd like very much to do more with Trio X. My collaborations with Joe McPhee and Jay Rosen have been very enjoyable, as well as fruitful. I have other relationships or musical interests of course—a duo with Ivo Perelman, with whom I enjoy working very much. There will be a lot more from Ivo and I.

A guitar trio with Tim Siciliano [guitar], and a young drummer named Chris Covis. We will be recording and touring for Wild Rose Studios and Records located in Oregon, in March, 2011. More to come on that, at a later time.

Jimmy Halperin is one of my favorite saxophone players. One of the most gifted people I've ever come across. I've known Jimmy for almost 30 years, and his development is truly spectacular. There's a lot more to come from Jimmy and I, including the project we might put together on NoBusiness Records—some of Charles Mingus' material. But these things take time. Mingus wrote music for the gods; mostly large ensemble arrangements. Doing them in a duo will take some thought, as well as patience on our part. All this takes rehearsal; they take thought, as well as organization.

I have said many times that music is mostly about organization. Choosing repertoire, deciding how to play this repertoire, all these things. I mean look, you guys at NoBusiness just put out a Monk record of ours—that's a very well constructed and organized recording. In terms of my playing, it allows you to hear the music without it being too rigid. I'd like to play more music like this. To incorporate virtuosity with a freedom of the more flexible improvisational style associated with free/modern jazz styles. All this while still maintaining the ideas of the composer. I enjoy working within these ideals and styles. It's very challenging to me.

So if you are asking me, "What should people expect from me," hopefully more of the same, but different. To continue to build on a body of work that [listeners] as well as performers think is excellent. I don't know how else to put it. I just want to make good music. Ellington said "There are just two types of music—good and bad." I want to make good music. I don't have any major plans for having any large bands, huge orchestrations. It might happen. I just might find the time in my life and reasons for doing something like this, but right now it's just to make the best music that I can make. And utilizing all my abilities, which are getting to be more and more extensive.

Selected Discography

Dominic Duval/Jimmy Halperin, Music of John Coltrane (NoBusiness Records, 2010)

Dominic Duval/Cecil Taylor, The Last Dance Volumes 1 and 2 (Cadence Jazz Records, 2009)

Charles Gayle/Dominic Duval/Arkadij Gotesman, Our Souls. Live In Vilnius (NoBusiness Records, 2009)

Dominic Duval/Jimmy Halperin, Monk Dreams (NoBusiness Records, 2009)

Trio X, Live in Vilnius 2L (NoBusiness Records, 2009)

Michael Jefry Stevens/David Schnitter/Dominic Duval/Jay Rosen, For the Children (Cadence Jazz Records, 2008)

Dominic Duval/Jimmy Halperin, Monkinus (CIMP, 2007)

Ivo Perelman/Dominic Duval, Nowhere To Hide (Nottwo, 2008)

Dominic Duval/Ron Lawrence/Gregor Huebner/Tomas Ulrich, Mountain Air (CIMP, 2007)

Dominic Duval, Songs For Krakow (Nottwo, 2007)

Paul Smoker/Ed Schuller/Dominic Duval, Duocity In Brass And Wood (Cadence Jazz Records, 2004)

Trio X, Journey (CIMP, 2003)

Dominic Duval String & Brass Ensemble, American Scrapbook (CIMP, 2002)

Ivo Perelman/Dominic Duval/Mark Dresser/Jay Rosen/Gerry Hemingway, Double Trio (Boxholder, 2001)

Dominic Duval's Quintet, Cries And Whispers (Cadence Jazz Records, 2001)

Cecil Taylor/Dominic Duval / Jackson Krall, All The Notes (Cadence Jazz Records, 2000)

Cecil Taylor Quartet, Qu'a Yuba (Cadence Jazz Records, 2000)

Trio X, Watermelon Suite (CIMP 1999)

Bob Magnuson/Tom DeSteno/Jemeel Moondoc/Dominic Duval, Omens (CIMP 1999)

Trio X, Rapture (Cadence Jazz Records, 1998)

Joe McPhee & Dominic Duval, The Dream Book (Cadence Jazz Records, 1998)

Dominic Duval/C.T. String Quartet, Navigator (Leo Records, 1998)

Dominic Duval, Nightbird Inventions (Cadence Jazz Records, 1997)

Dominic Duval's String Ensemble, State Of The Art (CIMP, 1997)

Michael Jefry Stevens/Dominic Duval Quartet, Elements (Leo Records, 1996)

Photo Credits

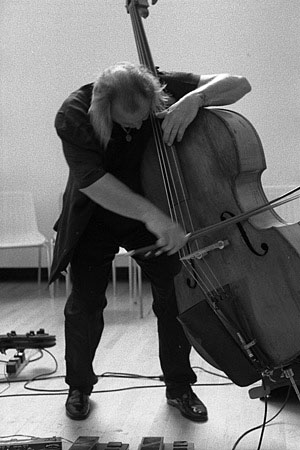

Dominic Duval

Page 3: Courtesy of NoBusiness Records

Page 5: Peter Gannushkin, Downtown Music Gallery

Page 7: Susan Oconor

Page 8: Frank Rubolino

Tags

dominic duval

Interview

Maxim Micheliov

United States

New York

New York City

Cecil Taylor

Joe McPhee

Mark Whitecage

Ivo Perelman

Jimmy Halperin

Jay Rosen

Thelonious Monk

John Coltrane

Charles Gayle

Glenn Gould

Michael Stevens

Albert Ayler

Paul Chambers

Miles Davis

Philly Joe Jones

Red Garland

The Beatles

The Rolling Stones

Jimi Hendrix

Charles Mingus

Otis Redding

Wilson Pickett

Aretha Franklin

Jimmy Lyons

Sunny Murray

Wayne Shorter

Jimmy Garrison

Elvin Jones

McCoy Tyner

Sonny Rollins

duke ellington

Count Basie

Thad Jones

Mel Lewis

Slide Hampton

Louis Armstrong

Fats Waller

Scott LaFaro

Jimmy Blanton

Jimmy Woode

Oscar Pettiford

Bill Evans

Ornette Coleman

Stan Getz

Ron Carter

Richard Davis

Ray Charles

Bill Dixon

Kronos Quartet

Tomas Ulrich

Jason Kao Hwang

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.