Home » Jazz Articles » SoCal Jazz » John Patitucci: The Quintessence of Acoustic and Electric

John Patitucci: The Quintessence of Acoustic and Electric

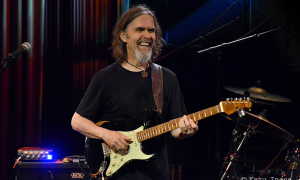

Courtesy Gus Cantavero

The rock bassist that influenced me the most was Paul McCartney. We wore out Abbey Road. But what was even more powerful were the funk grooves of James Jamerson, Willie Weeks, and Chuck Rainey.

—John Patitucci

Fast forwarding to the present, Patitucci is now fifty nine years old and considered by many to be the most talented bassist on the planet. Particularly, when you consider he has mastered both the electric and acoustic on a virtuosic level.

A conversation with the consummate professional showcased his words and stories to be as strong as the voice he shares on his instruments.

John Patitucci: Jimmie we did it!

All About Jazz: Hi John, yes we persevered and finally connected. Getting late for you on the east coast. Long day?

JP: Long day in the studio, but it has been really exciting the past couple of days. We recorded some new curriculum to be released later in the year.

AAJ: That's cool. I knew you had been spending time in the studio working on something.

JP: Well, what's cool is that this is all recorded in context. I wrote several tunes that will help one to be able to focus on a certain stylistic thing on the bass. I do it in context, with a group. On the first day I hired Adam Cruz on drums and a Cuban pianist named David Perelas to come in along with the great guitarist Adam Rogers. Perelas can swing like Bud Powell, but also has that historical knowledge of the Afro-Cuban folklore. We played some tunes I wrote and also a contrafact I did on "Autumn Leaves." I wrote a guajira as a way of getting them into the song closet. David really expanded on it and did like a tutorial on the historical aspects. It was amazing. Then we stopped and talked about it a bit. A chance to see how everyone is doing with it and feeling about it. Today I had saxophonist Chris Potter, Rogers, John Cowherd on piano and Nate Smith on drums.

AAJ: Nice group. What were you working on today?

JP: We did kind of a funky little tune a la The Meters. The idea being to get cats to learn a little bit about how a rhythm section works in that kind of a groove. The interlocking parts that make it work together kind of like a puzzle. It's a lesson in improvised music that includes the soloist and all the parts. I will then break it down into smaller pieces and talk about the technical flexibility you need to have in order to play some of the shapes and chords on the bass. It's all about learning the bass in context. I want to teach in a way that will prepare one for playing with a band.

AAJ: That's a very practical approach that makes a lot of sense. It's like learning to drive in wide open spaces with no one around. It's going to be way different when you are on the freeway in heavy traffic.

JP: Yes. It has also been a challenge to bring forth all that I have learned. It's a challenging thing to do, as a teacher, to keep students engaged and so that they don't get discouraged. I instill those very principles that are the same as when you get to a bigger stage where there is more advanced improvisation and more responsibility on the rhythms. Some guys are very good around the neck and have some instrumentation on the bass. They know the scales and arpeggios, but can't play a gig yet. They don't know how to groove or to come up with a bass line that can be replayed in a two or four bar pattern. How to lock in with the drums. Its really a tall order when I try to take everything I have learned over several decades and try to jump start a young musician into this whole world.

AAJ: Also top of mind for me is the documentary on your life, Back in Brooklyn (August Sky Films, 2016), which I frankly saw only recently. The piece is very well done, not at all dry like some documentaries. For me, that was the case because although there was of course a lot about your music, it was personal with a focus on you and your family. Was that your intent going into the project, or was someone else driving the wheel?

JP: Yes, I suppose there was. My ex brother-in-law, who used to be married to one of my sisters, had this idea to do a documentary on me. He has a theater background and really wanted to do it. I wasn't so sure about the idea. They do biographies on guys like Miles Davis and Wayne Shorter, not me. I'm a lot younger and I just wasn't so sure that it was a good idea. I just didn't know that my music had this overarching foundation like those cats had accomplished.

AAJ: Maybe asking yourself, "Am I that old already?"(with a laugh)

JP: (laughing) Yeah, something like that. What I really wanted to do at the time was a new record. So my brother-in-law offers to front me the money to make a new record if I will let him do the documentary. I said, "Deal."

AAJ: For sure. Immediate funding is not always that easy to get. No way you turn that down.

JP: Yeah, and it worked out real well. The record, Brooklyn (Three Faces Records, 2016), did very well and I was able to pay him back pretty quickly. I wanted to get a big semi-hollow electric bass built that would give me that big warm sound so that I could play walking bass and with those open ended prettier high end notes for soloing. I had it made by hand and it is such a beautiful instrument. For sometime I had the idea and the compositions for the two electric guitars concept. We did it with Brian Blade on drums, and both Adam Rogers and Steve Cardenas on guitars. So anyways he wanted to come into our lives and film. It turned out to be a lot of fun. You can see the hilarity and the laughter when we are rehearsing in my basement. That's all very genuine. Those guys are like family to me.

AAJ: There's a lot of depth and intelligent interplay going on with that quartet. You don't see the two guitarist concept too often. It's a bit more unique. What led to you having that alignment?

JP: Well, I have played with Adam for quite some time now. He is an absolute cyborg on the guitar. A completely amazing guitarist that can play anything from jazz to classical with equal aplomb. From Jimi Hendrix to rhythm guitar and everything in between, Adam is just incredible. Now, Steve I met when I was living in L.A. He is a phenomenal player. I mentioned the idea of having two guitarists to Adam. He liked the the idea and when I mentioned Steve as a possibility, Adam was immediately on board. He started talking right away about how much he liked the way that Steve played. They had met and hung out just a little bit before, but the chemistry between them is way more than I could have ever imagined. The way they make space for each other and comp for each other is like they are reading each other's mind.

AAJ: Well, when you then factor in the weight of your playing, it's amazing that you guys aren't running into each other.

JP: Your'e right, Jimmie. That's exactly the thing. Then you have Brian orchestrating on drums. He creates spaces and plays with such intensity. He can play softly and keep the intensity. Brian has a wide dynamic that can take you over the mountain tops, but then come down in a whisper in an instant.

AAJ: It's certainly a quartet of equal measure that shines both collectively and individually. In the documentary, we quickly learn that you come from a typical large Italian family. Boisterous, with a brother and three sisters— playing ball out in the street—running inside when the pasta was ready—lots of music being heard around the house. A family life that is very relatable. Playing a musical instrument, however, was new to the mix. Not something that ran in the family. You and your older brother Tom heard lots of music, but what was the spark that interested you in playing it?

JP: My grandfather on my mother's side played a little piano by ear. His father had a speakeasy during prohibition and my grandfather heard some piano players he liked. He liked Earl Hines and Eubie Blake. He was kind of a wild early Renaissance character kind of guy that not only loved music, but also learned how to cook from his aunt in Naples. His family came to the United States in the late eighteen hundreds. He was born in Brooklyn in the early nineteen hundreds. He fought in World War Two with Patton (General George Patton) and received a Purple Heart. He also could make dresses. I remember him with pins in his mouth and a mannequin. My mother was involved with making McCall's patterns, but he was just very creative. He was also a longshoreman—a tough guy, and the best chef in the family.

AAJ: Wow, that's incredible that he did all those things.

JP: Yes, he was a very interesting man. On top of all of that, he worked for a time on the city streets with a jackhammer. It was during that time he came across the Wes Montgomery and Art Blakey records.

AAJ: Ah yes, the famous box, mentioned in the documentary.

JP Yeah, he came across this box of records that had been put out to the curb for trash pickup. We concluded later that we were the beneficiaries of a domestic quarrel. These weren't the kind of records that you just throw away. Nobody would throw away these records (laughing).

AAJ You wouldn't think so, other than an angry spouse (laughing). But I love the story of the box.

JP: My brother, Tom, and I just marveled at these records. It really is what set things in motion for us to start playing. We didn't even understand what we were listening to. But we knew there was something there to be discovered. Wes Montgomery started to draw us in with his soulful blues and swing. That real earthy sound of his. That's also when I first heard Ron Carter. In the box I also remember an Oscar Peterson record with Ray Brown and Sam Jones.

AAJ: Well, your grandfather led quite an adventurous life. What about your father?

JP: My dad grew up in a huge family with twelve kids. He was the youngest and used to work in a hat shop with his father, who was from Calabria. My grandfather Patitucci came over from the old country when he was sixteen, didn't know anybody and had to bribe somebody with money just to vouch for him so that he didn't get sent back on the boat. He was extremely poor. His father had died and he had started working on his uncle's farm when he was age five. A rough hard life at first in Southern Italy. Things have to be bad when you get on a boat at age sixteen and sail off somewhere where you don't know anybody. The family of origin on both my sides of my family sound like a Scorsese film. All these amazing characters.

AAJ: Such an inspiring lineage. Thanks for sharing all of that. You mentioned your brother, Tom. He became a pretty fine guitarist, and you two have been very close all your life. You are prideful when you speak of Tom the brother, as well as Tom the mentor, and Tom the guitarist.

JP: We are very close. Real close. My older brother and I are like twins born three years apart. My grandfather really encouraged us regarding music and we were really into that.

AAJ: He went well beyond bringing home the box.

JP: Very much so, yes. He bought my brother a guitar and started him on lessons. He was having him learn how to read music. So, naturally I wanted to be like my brother. I had a good ear but I was left-handed. The pick felt weird in my hand. I hated it. I couldn't get a feel for it so I quit. But my brother, in his ever astute manner, thought if we were going to be able to play together that I should play bass. We found a Sears TeleStar bass that we were able to buy for ten bucks. It buzzed on every fret, but I loved it. I thought it was the greatest thing in the world.

AAJ: How old were you?

JP: I was ten. Before that I was playing bongos and maracas. We moved out to Long Island about that time and I was in the concert band. I had taken some pad lessons, was working on the rudiments, and was playing the drums. I really wanted to play the drums, but my dad wouldn't let me. So, then I put my full attention to the electric bass.

AAJ: Interesting how that all came together. Early on then you were listening to rock, pop, Motown, jazz— everything that was on the radio. You have mentioned John Entwistle and John Paul Jones among bassists that influenced you. So, you clearly were digging hard rock such as The Who and Led Zeppelin. Possibly some others with powerful bass lines like, Jeff Beck, Cream, and Humble Pie. Listing Entwistle first, you had to be into the classic Who's Next(Track Decca, 1971), right.

JP: Who's Next was a huge one. Tom and I listened to that over and over so many times. Yeah, we listened to all that you mentioned and then some. The bassist that influenced me the most, however, was Paul McCartney. We absolutely wore out Abbey Road (Apple, 1969). Revolver (Capitol, 1966) and Rubber Soul (Capitol, 1965), as well. But we really wore out Abbey Road. Those were the rock influences, but what was even more powerful, frankly, were the funk grooves of James Jamerson, and Willie Weeks on Donny Hathaway Live (Atco, 1972), and also Chuck Rainey on a bunch of stuff. When I was thirteen my family moved out west to the Bay Area. I was very fortunate to have Chris Poehler as my mentor. He really hipped me to a lot of jazz and R & B stuff. He first played me Chick's [Corea] music and Herbie's [Hancock] music. I had heard Jamerson on all those Motown records. Listening to Stevie Wonder was the first thing that made me really want to play bass. But they really didn't list or credit the names back then. I didn't even know I was listening to Jamerson. "I Was Made To Love Her" and "For Once in My Life" used to freak me out every time they came on the radio. The bass mix was really loud and I really gravitated towards it. But I didn't even know why. I just felt something.

AAJ: It just really resonated with you.

JP: Yeah, it really did.

AAJ: I love that by age twelve you not only wanted to be, but knew that you were going to be a professional musician.

JP: It was perhaps a very naïve statement that I made to myself. But I knew that I just wanted to learn to play music and that was it. I didn't care about anything else (laughing). I mentioned Chris Poehler, I should say that Chris was a very talented musician who had played a little bit with Wes Montgomery and Earl "Fatha" Hines and Chet Baker and other greats that came through the Bay Area. My intermediate school band director saw and heard something in me, even though I didn't read well, but I had a really good ear. He would let me just blow on some blues tunes. He more or less turned me over to Chris, who was a much more advanced player than he was, to try to help guide me. Chris pushed me to learn how to read. He demanded that I learn how to read. I really hated it. But I'm so glad he made me learn it. Then, as I said before, he turned me on to so much music, and also introduced me to a lot of people in the music business. When I was fifteen I started playing the acoustic bass. Because of Chris I was able to go to San Francisco State and play with the symphony. My first year of college was my first serious year of classical instruction on the double bass with the bow. I felt so overwhelmed because I was only seventeen. There were guys in the bass class that were seniors who were just burning on Bach suites. I had a very intense year and then my family moved to southern California. I spent 1972 through the summer of 1978 in the Bay Area and it was a very pivotal period in my life.

AAJ: You landed in Long Beach. That's when a lot of things started to click. What were the highlights of that period in your life?

JP: I spent two more years on classical bass at Long Beach State. I lived in Huntington Beach for four years. There were a lot of people my age and I started playing a lot of gigs. Bebop gigs on acoustic, funk gigs on electric, weddings, all sorts of stuff. Before that, I forgot to mention that I played in my brother's band when we were still up in the Bay Area. We were playing weddings and stuff as well. The great bassist Jay Anderson left southern California to go play with Woody Herman, not too long after I arrived. I ended up inheriting most of his gigs. So, here I am, eighteen years old, playing all these gigs and going to school. Then between my sophomore and junior years I went out on the road with Gap Mangione. I got my first taste of touring playing electric bass that summer. Things got interesting after my junior year. My classical teacher wanted me to put all my focus into classical music. He wanted me to stop playing any and all other music. I didn't so much like that idea. I didn't want to give up all this other music that I really loved. So, we butted heads a few times and I finally decided to quit school. I have never looked back.

AAJ: That's a shame that his insistence cost you that final year. Clearly, though, it hasn't hindered your career in any way.

JP: I had been around classical music my whole like. It was played at the house when I was a kid. I truly love and enjoy classical music. My teachers always saw how much passion I put into it and how much I got out of it. I can understand that by appearance it would seem that I would want to dedicate myself to classical music. But I couldn't do that. There is so much more to be appreciated.

AAJ: Well, instead of that fourth year of college you embarked on a different learning experience playing with a lot of cats in the L.A. area.

JP: A ton of people. Victor Feldman, Lenny Breau, Joe Farrell, Freddie Hubbard, and all kinds of people.

AAJ: Freddie Hubbard. Man, I loved the way he played.

JP: Me too, Jimmie. I didn't get to play with him all that much, but I'll never forget the way he played. What an improvisor. I was a big fan of his records, just like you, but playing with him was astounding. His level of time playing and his creativity, with that incredible sound and chops. I also played with Dave Grusin and had the opportunity to play with a bunch of very talented Brazilian artists, as well. All these things were happening and I was doing session work too. I started getting some television and film gigs. I was getting all this experience. I was playing in Victor Feldman's trio and we did a gig at Chuck Mangione's home. I think this was about 1984. Gayle Moran, Chick's [Corea] wife, was there and sat in on the piano. We were playing some bebop and having a good time. Later on, she goes home and tells Chick about this little Italian kid on the bass. She told him that he just had to hear me play. Chick and Gayle used to have Valentine's Day parties at their house every year. They loved Victor Feldman, who had played with Miles [Davis] and wrote "Seven Steps to Heaven." He was an amazing player. So they invite the trio, that also included Victor's son on the drums, to play in their living room.

AAJ: It served as an audition.

JP: The funny thing is that I had been trying to get an auction with Chick. I was also playing in Joe Farrell's band and I kept asking him when Chick was going to have auditions. He told me that Chick never really has auditions. So, anyways, Chick hears me play the acoustic bass at his house and then tells me to send him some of my electric playing. He was looking to start an electric band. I sent him some stuff, he listened to it, he told me on the phone that he liked it, but that was it. I figured that he didn't like it all that well because there was no mention of doing anything. Two or three weeks later I was taking a break in between takes at the studio. We had a very funny and sarcastic engineer named Wally Krantz. I'm in the lounge, and I hear him say over the intercom, "Patitucci, Chick Corea is on the phone." I said, "Yeah, that's funny Wally," as I hang up the phone—click. He does it again, and I still think he is messing with me, so I hang up the phone again. Third time, Wally says "You idiot, pick up the phone, it really is Chick Corea." What happened next is something that I will never forget for the rest of my life. I pick up the phone and Chick says, "Listen I know you have a lot going on and are playing with a lot of different people, but I was hoping you would consider joining my band."

AAJ: Wow, no considering needed for an opportunity of that magnitude.

JP: Oh man, I wanted to jump through the phone. It was an unbelievable moment in time.

AAJ: For sure, and of course you went on to play in Chick Corea's Elektric Band and his Akoustic band as well.

JP: Yes, and with all the challenges and mentorship that raised my playing to a whole new level. My very first gig with him was on the Merv Griffin show. Herbie Hancock played with us. Tom Brechtlein was playing drums. Dave Weckl hadn't joined the band yet. I was actually the first guy hired.

AAJ: We suffered the loss of Chick Corea earlier this year. Having played with and known the man for many years, it would be wonderful if you could say a few words about Chick as a musician, a composer, a friend, a human being, in any manner you feel comfortable talking about him.

JP: Chick saw me in a way that maybe a lot of other people didn't. He gave me a lot of room to blow and play. He challenged me. His comping was so powerful that I felt like I was in the ring with Muhammed Ali. He played those sharp chords that forced me to become much more declarative rhythmically and when I played my ideas on solos. He believed in my compositions. He said that I should have my own band and be making records of my own. I asked how that was going to happen, as it didn't seem likely. He said not to worry and just like that he went out and got me a record deal. He believed in me. He produced that first record, John Patitucci (GRP, 1987), and taught me how to organize myself and to make records. All of a sudden I was making records every year. I was flying out Michael Brecker and all these other different people. The records did well. The record company didn't really want to sign another bassist, but the first record was number one on the jazz Billboard chart. It was nominated for a Grammy. I just couldn't believe it. I just kind of laughed and thought that this couldn't actually be happening. Chick was a very kind man. A very generous man. We had a great chemistry and dialogue together. Certainly in the Electric and Acoustic bands, but also in the very special quartet with Bob Berg and Gary Novak. We had a blast touring Europe with that group. Chick was a beautiful soul. When he started his own label, my record, The Heart of the Bass (Stretch Records, 1972) was the first one produced on that label.

AAJ: I had the pleasure of speaking with him just this past November. He couldn't possibly have been more genuine, down to earth, quick to laugh, and full of energy. He was very generous with his time and we spoke about a great many things. We talked quite a bit about his ability to make an audience relax and feel comfortable as if they were sitting in his living room. I've experienced that as an audience member, but you experienced it countless times from the stage. What effect did that vibe he created have on you and/or your bandmates? It no doubt created a heightened attentiveness from the crowd and consequently a richer listening experience.

JP: I would say that it was organic. My approach has always been to never let anything get in the way of playing my instrument. Chick, sometimes, would get annoyed by somebody falling asleep in the front row or someone just not digging it. He would find that one person in the entire audience and sometimes get frustrated with that. I have always refused to let that happen. We had a lot of eye contact on stage. We were digging it and having fun. Chick had the mindset that the audience was never wrong. That it was our job to pull them up and encourage them.

AAJ: Indeed, he said those very words to me. He, of course, goes down in history as one of the most prolific composers and musicians in history. Thanks for talking and giving us some insight about Chick Corea.

JP: Yes, well I will share one aspect of his songwriting process. He taught me to let the ideas flow. That once you have something creative going on, don't stop to analyze it. Just keep going and going for as long as that burst takes you. Then you can look back and make sense of it all. But let it all out before you begin to take perspective of it.

AAJ: That's interesting. It's easy to picture someone agonizing over the next note, perhaps overthinking, and getting stuck in the mud. The methodology you spoke of would seem to make a lot of sense. On the subject of songwriting, you recently created a song that evokes the memory of bassist Paul Jackson. In fact, the video of the song and the heartwarming open letter you wrote to Jackson's family, which was released today (April, 21, 2021). What can you tell us about Letter for Paul?

JP: Yeah, yeah, I'm glad you brought that up. I didn't even realize that it was coming out today, but then my wife pointed it out and I was very happy about that.

AAJ: What's the back story as far as meeting him and what it is about his playing that resonated so much with you?

JP: Well the irony is that I never did meet him. Chris Poehler knew him very well and turned me on to him. Chris played acoustic and electric, and Paul played acoustic and electric as well. When Paul got on the electric something special happened. His jazz flexibility and freedom coupled with his chunky earthy blues and soul created this crazy improvisational funk. Paul was a co-founder of the Headhunters with Herbie. Chris was at the studio many times when they were recording. I freaked out when I heard Paul play. The buzz in the Bay Area at that time was that you had to learn how to play like Paul, Rocco Prestia (Tower of Power) and maybe the slapping of Larry Graham, who, of course, played with Sly and the Family Stone and then Graham Central Station. For me, it was really Paul and Rocco. In fact, they still are. I feel like they gave me a lot. I came to find out that Paul was a lefty, just like me. His power and soul just gripped me. He played a lot of backwards grooves, which I love. Weckl and I ended playing a lot of backward groves with Chick. I still play them a lot. Anyways, he shook me to my core and I ended up learning all the Headhunters tunes. I was just blown away by the fact that he played all this improvisational jazz stuff but at the same time with this super funk thing going on. It was a wild combination. On top of that he had a very expressive way of shaping notes. So, needless to say his music and moreover his style of play has meant a great deal to me.

AAJ: How did this new song come about?

JP: You know, I honestly didn't even know that Paul was sick at the time. We were in a studio in Brooklyn and had a little bit of time left. It was suggested that I just play some kind of instrumental. So, it was natural for me to go into a Paul Jackson kind of thing. We just went into something that had a Herbie early seventies funk kind of vibe. Paul had a way of creating different grooves throughout the course of the song. I wasn't so sure I was really doing that all that well, but the other guys were really into it and playing really well. We listened back and were surprised, really, at how well it came out. It was a jam that I edited. I made it a little shorter, added a six string solo, and a little percussion. Chris Potter really knocked it out of the park, so we kind of made it a Potter tour de force. This was also with John Cowherd, Marcus Gilmore, and Adam Rogers.

AAJ: That's kind of cool actually that the song was created organically and became a tribute in a natural way. There's a lot of heart and genuineness in the corresponding letter you wrote. Now picking back up to being in southern California when you were younger and only a few years out of college, you ultimately determined California wasn't your scene and moved back to New York. I'm sure there were other considerations, but you were quoted as saying that "you can't make snowmen in California."

JP: (laughing out loud) I really missed the seasons. Of course, sometimes you get tired of the snow. But we really love it here. Creatively its insane. If I was wealthy, I'd love to have a house in California as well. I have a lot of friends there and family too. My brother, Tom, still lives in northern California. I have a sister that lives in California. My oldest daughter is a singer songwriter, and lives in Los Angeles.

AAJ: Tell us about your daughter.

JP: She is very talented in a lot of different ways. She wrote a beautiful jazz ballad for vocalist Andy James. We wrote a cool Brazilian tune together. She's twenty-three and does some R&B and some other things with a little hip-hop influence. When she does more of a rock thing she has a phrasing that is kind of a female Jim Morrison deal.

AAJ: Wow, how cool is that?

JP: Yeah, she's talented. She can go in a lot of different directions. She is in a film that I scored last year that is coming out in May. It's called Chicago: America's Hidden War(CineLife Entertainment, 2021). It's all about the gang violence, police corruption and abuse, government corruption, and the whole thing. I wrote the score and my daughter sings on parts of the score. She did a really great job on this project.

AAJ: Thanks for sharing that. What does she go by?

JP: Her name is Gracie, but she goes by Sachi Grei Sato. Sachi is my wife's first name and Sato is my mother-in-law's maiden name.

AAJ: You clarified oldest daughter. Is your younger daughter musically inclined as well?

JP She has a good voice, but right now she is concentrating on her education and getting her business degree in fashion from Tulane University.

AAJ: And your wife, Sachi, is a professional cellist, correct?

JP: Yes she's a cellist. She also received a professional certification from Berklee in film supervision. She actually did the music supervision on the film that I scored.

AAJ: You must have some fun and interesting jam sessions together at home. Do you play a lot of classical music, or will she occasionally surprise you with "Baba O' Riley?"

JP: (laughing) We do play together. Actually she has been on several of my records.

AAJ: That's great to have such a musical family. For many years you have been sharing the stage as part of Wayne Shorter's band. That's as far up the food chain as it goes in terms of playing with an icon. How long have you been connected with him, and just how amazing is it to play with such a master?

JP: Well, I started with Chick in 1985 and he introduces me to Wayne in 1986. In 1987 I played on his record Phantom Navigator (Columbia, 1987). I played with Chick until 1995. Since then I have toured and recorded a lot over the years with Wayne.

AAJ: Trying to get just a glimpse of Shorter's genius, I wanted to ask about the concept of introducing the music at zero gravity. This would seem to be a very interesting Shorter methodology. Perhaps you could expand a bit on how you and fellow quartet mates, Danilo Pérez and Blade, go about accomplishing that.

JP: His whole concept is that you want to blur the line between composition and improvisation. Wayne doesn't want the music to be predictable. He doesn't want people to know when we are improvising and when we are playing the written music. Anyone can cue into one of the pieces that we have in the book, and there is a lot of them. Sometimes we will improvise for forty-five minutes before playing a written composition. But people don't know that and will ask what the name of the first tune we played is (laughing). It's easy to think that because there are grooves and melodies. It's tonal. By design Wayne has given us that freedom. It's been the same quartet, with the guys you mentioned, Brian and Danilo, for about twenty years now. So there is a broad chemistry whether we are improvising or interpreting the written note. Wayne is amazing. He will write this masterpiece of orchestration that we read through and then he will say something like, "let's just play page seven and eight." We will be thinking how could you leave all this out. But Wayne has a very light touch on what he writes, even those it's genius.

AAJ: In the documentary, you mentioned Shorter often referring to "the mission" when you go out to play a gig? What can you tell us about the mission?

JP: Wayne wants us all to play music like the way we want the world to be.

AAJ: Wow, that's a statement with some weight behind it.

JP: Yeah, he'll say, "Let's go make a movie" and want to take people on a visual journey. He wants people to dream, feel things, reach for things, and feel inspired. Wayne is interested in uplifting people. It's more about touching someone emotionally and making them cry, then it is about impressing them. You know what I mean?

Comments

Tags

SoCal Jazz

John Patitucci

Jim Worsley

United States

New York

New York City

Adam Cruz

David Perelas

Adam Rogers

Bud Powell

Chris Potter

John Cowherd

Nate Smith

The Meters

Miles Davis

Steve Cardenas

Jimi Hendrix

Earl "Fatha" Hines

Eubie Blake

Wes Montgomery

Art Blakey

Ron Carter

oscar peterson

Ray Brown

Sam Jones

John Entwistle

John Paul Jones

The Who

Led Zeppelin

jeff beck

Cream

Humble Pie

Paul McCartney

James Jamerson

Willie Weeks

Donny Hathaway

Chuck Rainey

Stevie Wonder

Chet Baker

Jay Anderson

Woody Herman

Gap Mangione

Victor Feldman

Lenny Breau

Joe Farrell

Freddie Hubbard

Dave Grusin

Chuck Mangione

Gayle Moran

Tom Brechtlein

Dave Weckl

Michael Brecker

Bob Berg

Gary Novak

Paul Jackson

the headhunters

Rocco Prestia

Larry Graham

Sly and The Family Stone

Graham Central Station

Marcus Gilmore

Andy James

Jim Morrison

Wayne Shorter

Danilo Perez

Bill Cunliffe

John Beasley

Concerts

Jun

15

Sat

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.