Home » Jazz Articles » SoCal Jazz » Dean Brown: Global Fusion on Acid

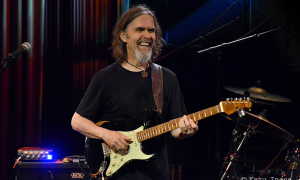

Dean Brown: Global Fusion on Acid

There is just more of a sense of urgency to the east coast vibe. There's a fire, a reckless abandonment sort of thing.

—Dean Brown

From the outset, the equation was simple enough. Jazz + rock = fusion. However, whether it was Miles Davis, Larry Coryell, John McLaughlin, or any of the pioneers of fusion, the music has always been far from simplistic. Musical depth has long been the trademark of a genre that has been through many incarnations and traversed a multitude of directions. Jazz and rock has been supplemented through time by funk and Latin and other enriching flavors of sound.

Guitarist Dean Brown has been at the forefront of invention throughout his musical journey. Soon after graduating from the prestigious Berklee School of Music, Brown began playing with top of the line artists such as Brecker Brothers, Billy Cobham, Marcus Miller, David Sanborn, Steve Smith, Bill Evans (the saxophonist, not the pianist), and many more.

You need look no further than his record Rolajafufu (Self Produced, 2016) to hear and feel his broadened, global fusion scope. The title says it all in that it rolls together the first two letters of rock, Latin, jazz, funk, and fusion. Brown keeps on rolling and is as energized and engaged in conversation as he is on stage.

All About Jazz: I'm guessing that close to 90% of all the interviews you have ever done have started out with the fact that you were born in France and moved around a lot due to your dad being in the military. I thought maybe we would be bold and dive into something else. Like maybe right into the present. Live music is inching its way back, hallelujah, and I know that you're part of it. Catch us up on your band, what's going on, and just how it all came together. Maybe talk a little bit about Marvin "Smitty" Smith, Gerry Etkins, and Ernest Tibbs. They've been playing with you for some time now.

Dean Brown: Yeah, great. It does go back several years now, especially with Gerry and to a slightly lesser degree with Smitty. It goes back to Boston. We all went to Berklee. I graduated in 1977 and Gerry graduated the next year. Smitty went there in the late seventies to early eighties. We were in the wave right before guys like Branford Marsalis and Jeff Tain Watts. Smitty went out to California before I did because Kevin Eubanks, who we also went to school with, asked him to be the drummer on the The Tonight Show. He did that for many years. Gerry soon followed, within the next year or two, and played on The Tonight Show for many years as well. I was doing my thing, gigging in Europe and stuff, then my wife (artist Ruth Brown) and I moved out to California about ten years later. I was tapping Gerry and Smitty to bring that east coast vibe. Gerry and Smitty were always threatening to put something together when they were sitting around on the NBC set. They would just jam together and come up with ideas. They would say that they should book some gigs and try to do something. But they never did. I finally told them that I was sick of hearing about it (laughing), let's just do it. We put together a gig with a wonderful bassist named Dave Carpenter.

AAJ: He was a very talented guy, makes me think of him playing with Peter Erskine.

DB: Yeah, that's the guy. He passed away a few years ago, but Dave and I used to play in a trio with Billy Cobham. I have been in many incarnations of Billy Cobham groups. Dave was the best bassist I had played with out here (west coast). I don't like playing with people based on other people's suggestions. I need to hear them play. I don't mean on a record, I need to hear them play live.

AAJ: Yeah, well, just because it sounds good to somebody else, that doesn't mean it necessarily will to you.

DB: Yeah ,and I've been burned on that, well maybe not burned, but they may be a great musician, but do they speak to me?

AAJ: Do they necessarily fit with what you are doing?

DB: Right, right. So I thought a quartet with Dave would work and get something going. We started playing at the Baked Potato every Wednesday night. We played a lot of original music and started to get a following. There was high level of care put into our music. A lot of us sort of brought that east coast vibe to it.

AAJ: I've heard different descriptions of that east coast vibe variant. How do you define it?

DB: Well, I'll probably get in trouble for saying this, but I don't care. There is just more of a sense of urgency to it. It's less prevalent with west coast guys. West coast guys are strong on the technical side and maybe a bit more professional (laughing out loud). But it's not just about playing a lot of notes, there's a fire, like I said, a sense of urgency with east coast guys.

AAJ: You're not so much referring to the sometimes "laid back" term.

DB: No, not so much that. It's more of a reckless abandonment thing. There are exceptions, of course. George Duke is from the west coast. I don't think anyone would ever accuse him of not playing with reckless abandonment. Then, really there is a distinction between L.A. and San Francisco too. The Bay Area has a serious identity of it's own fire when you go back to Tower of Power and Cold Blood.

AAJ: Cold Blood, they were an inferno. Saw them in the early seventies. Just smoked the place. Tower was/is great, but Blood ran hot.

DB: Yeah for sure. Both those bands were coming out with phasers on kill. But, anyways I started to record a record with those guys. Around that same time I was playing with another great bassist that went to Berklee, Jimmy Earl. Also with Hadrien Feraud.

AAJ: Two more great ones for sure. I have to say that seeing Feraud fill in for Anthony Jackson playing a double bass between Hiromi and Simon Phillips was a remarkable show.

DB: Oh yeah. Well I got to know Hadrien through his father. His father was a guitarist that was a fan of mine (laughing). We've done a number of things together. He's played with my group with Smitty and Gerry and also a number of trio outings with Dennis Chambers. Then there is the whole Texas connection with keyboard player Bobby Sparks. He is currently playing with Snarky Puppy. A couple of years ago he released his first solo record, which is just fantastic. I met Bobby when he was playing with Roy Hargrove. Roy and his group were all from Texas, mostly the Dallas area. Dennis, Bobby, and I played a lot together as, for lack of a better term, an organ trio. Bobby had a B-3 at the core, but was surrounded by analog synths, and a lot of tools. But for the past twelve years or so my west coast band is a core group of Gerry and Smitty. Brandon Fields plays with us on a regular basis and has also played on my records. With the exception of DB111(B.H.M., 2010), that was a live trio album with Dennis and Will Lee. I like to have a lot of people contribute on my records.

AAJ: So when did Ernest Tibbs come into the picture?

DB: Oh, quite a while ago now. I think about seven years ago. You know our book of music keeps growing and the writing keeps getting more ambitious. I love having Ernest because he is so solid and plays every note with a purpose. Every note means so much to him. That's a huge confidence builder for a band to have a bassist that puts his entire being into every note. You can feel very comfortable and pretty much rest in those arms. Of course, I feel the same way when Hadrien is playing with us. That reminds me, you mentioned Simon Phillips. We played together about the time he was putting Protocol together. We had Jeff Babko and Everette Harp.

AAJ: Yeah, I saw Tibbs playing with Protocol one night.

DB: Yeah, that was a bit later when they had either Greg Howe or Andy Timmons on guitar.

AAJ: Yeah, it was Howe.

DB: It was a hell of a band when I played with Simon because we also had Alphonso Johnson on bass.

AAJ: Now that's a serious rhythm section.

DB: Yeah, there's a lot of fun things to talk about. Back in the eighties when I'd be in L.A. on some tour, I would book a night at the Baked Potato and get Tom Brechtlein or Vinnie Colaiuta. Been a long time now since Vinnie has played the Baked Potato (laughing).

AAJ: Kind of hard to sneak that in between gigs with Herbie Hancock and Jeff Beck.

DB: For sure. I would also get Tim Landers or even Jimmy Earl to come play.

AAJ: Well, it has come full circle with the Dean Brown Band with Etkins, Smitty Smith, and Tibbs playing the Baked Potato very soon.

DB: Yeah, in front of a live audience Saturday night April 24th. It's going to be great.

AAJ: I'm looking forward to the show.

DB: Not as much as I am!! (laughing)

AAJ: Well, I imagine that's true. I'll bow down to that (laughing). Time flies, it's hard to believe that it has been nearly five years since Rolajafufu. Will we hear some new tunes at the clubs? Do you have any plans to do some recording?

DB: Let me put it this way. The lion's share of the music that you are going to hear that night will be new material.

AAJ: Terrific. That's very cool.

DB: I hope I don't disappoint people that maybe have favorite tunes they want to hear. I will play a couple of tunes from the past, but we need to get movin' on. We had plans to do some things then the world kind of came to a stop. But that didn't stop the creative juices from flowing

AAJ: I referenced the cleverly titled Rolajafufu. Let's talk about that record. Your fifth record as a leader, the first time self produced. That had to feel pretty great to have that kind of support and appreciation from your fan base to help finance that project.

DB: That's right. Actually the two previous records were also mostly self produced. I had a little advance from the record company, but not much.

AAJ: Now that process then allowed you the freedom to do much more of what you wanted to do. To have that creative control. How much of an effect did that have on the recording and on the process itself?

DB: Well, to be clear, I have always had complete control on all my records.

AAJ: I'm glad to hear that, because I know that is often not the case.

DB: That's right. It's really the reason I didn't do my own record until I was in my forties. For example, there were a couple of record companies that were getting into the smooth jazz thing in the eighties and early nineties. They would come up to me and tell me how much they loved the way I played and that they would love to do something with me. So I would say that was great, let's do it, I have a lot of material that's been waiting to get recorded. I told them that I had been playing with a band on the east coast since the early eighties. They would say that it all sounded great, but then the next sentence out of their mouth would be to tell me what they needed from me. I would say what do you mean? With no disrespect what would make you think I need to know what you need in terms of opinions on my music? I'd been cultivating my own thing for a while.

AAJ: Yeah, so if you like my playing so much then why are you going to change it.

DB: Exactly. Exactly, right. They liked what they perceive that I brought to artists like Kirk Whalum and David Sanborn and Bob James. Those artists were able to keep their artistic integrity while also pleasing an ever-evolving contemporary smooth jazz audience. Bob James put it best in saying, "You better play what you believe in because if you do anything else the audience is going to know it." They didn't pander to a smooth jazz audience.

AAJ: Well, Sanborn and James were well established jazz players well before the smooth jazz thing came along. They didn't alter what they were doing. As you said, some of the smooth jazz folk just happened to like it.

DB: There's not a note that comes out of David Sanborn's horn that he doesn't believe. You can say the same of Kirk Whalum. So, anyways, these record company guys have this perception of me. As a sideman your job is to make the music sound as good as it can, and to give it what it needs to accomplish that.

AAJ: Basically you're playing someone else's music, that needs to sound the way that artist wants it to be. Not trying to fit your music into the space.

DB: Yes, so these guys are asking if I can do a Sanborn or Larry Carlton or Lee Ritenour kind of thing. Those are all great artists. They're the cream of the jazz instrumental crop. They all have a following. So why would I want to chase after that? What's the best that can come of that? Oh, it sounds kind of like Larry Carlton or it sounds kind of like Robben Ford. What's the point of that?

AAJ: You could just as easily go out and buy a Carlton or Ford record and listen to that.

DB: Precisely, that's exactly what I'm saying. Exactly the point. So that didn't interest me at all. I was fortunate to be playing with the top fusion and jazz artists. Guys like Billy Cobham, The Brecker Brothers, Vital Information, Bill Evans and David Sanborn.

AAJ: You have recorded a lot of great music over the years. You're on over two hundred records. Still whenever I hear or see your name I can't help but think of Vital Information. That band has weathered many changes over the years, but I do believe you played on Steve Smith's first Vital Information record. You were both Berklee cats back then. What's the backstory on that?

DB: Yes, I played on the first, second, and third records. It was all based on Steve Smith's need to have a creative outlet while he was playing with Journey. Steve and Tim Landers and the saxophonist Dave Wilczewski were all from western Massachusetts and had known each other a long time.

AAJ: Oh, so they knew each other as kids, long before going to Berklee.

DB: That's right. Landers brought me into the fold and we started playing as a quartet. But Steve wanted to have two guitarists on the record, which I thought was a great idea. Most other bands would have a keyboard player instead. Steve was coming from both the rock and jazz worlds and of course in rock guitar is king. The two guitar sound was more appealing to him to create something new and vibrant. So we went in to the studio to record what is now somewhat of a cult classic, Vital Information (Columbia, 1983), with Mike Stern as the added guitarist. It was pretty cool. He was comping for me and I was comping for him. We were sharing melody chores. That's two pretty fiery guitar players that know how to rock. When we started touring Mike had to opt out because he was playing with Miles Davis and on the cusp of doing his own thing. He put out the record Upside Downside (Atlantic, 1986) that was produced by Hiram Bullock. A lot of people think that was Mike's first record but there was another before that.

AAJ: Yes, Neesh (Absord Music, 1983). I have that on vinyl.

DB: It was a good record, but not quite like the next one. He had really flowered into such a great composer.

AAJ: Mike is an incredible composer. Neesh had Sanborn on every, or almost every track. It in some respects sounded more like a David Sanborn record. Not that that is a bad thing. Big fan of Sanborn as well. But, yeah, Upside Downside started the trademark sound he invented and has been successful with.

DB: Yeah, well that makes sense because I remember that Mike was filling in for Hiram Bullock in David's band back around that time. For that Vital Information tour, Steve was able to replace Mike with an absolute beast from Holland named Eef Albers. The guy was a great guitarist and a fine composer as well. We went on the road and played every little club in the United States. I'm sure Steve lost his shirt. He was playing in Journey at the time, so he could afford very expensive shirts (laughing).

AAJ: (laughing) Funny, but true. You know better than I that there are quite a few guys that have that big money gig as a sideman and do their own thing on the side.

DB: Funny story on that is from the great bassist Jimmy Johnson, who I also have played with. He plays with James Taylor. Now don't get me wrong, playing with James Taylor has to be as great as any jazz gig you could get as far as the musical fulfillment that you would get from it. But Jimmy would jokingly tell me that "he needed the money to support his fusion habit." (laughing)

AAJ: (laughing) Yeah, JT has the entire five piece Steve Gadd Band, including Michael Landau and Johnson, with him on his tours.

DB: Man, a guy like Jimmy—it's so cool. I mean how many guys are you going to see play with James Taylor one night and Allan Holdsworth the next. I would say that's a pretty cool life to have.

AAJ: I would say so. That's two way different ends of the spectrum. Then too, we were talking about Dennis Chambers. Playing with Santana was a jump starter for him.

DB: Dennis, though was already a known jazz drummer when he joined Santana. He had already been playing with John Scofield, The Brecker Brothers, and John McLaughlin..

AAJ: Indeed. I was referring more to the financial boon.

DB: Oh yeah, for sure. Working for Santana is like joining a corporation or something (laughing). I should bring you up to date with Dennis. He is recovering nicely from a health issue he had a few months ago. He is getting strength back and feeling better than he has in years.

AAJ: I'm so glad to hear that he is recovering well.

DB: He is doing great. I should mention that I wouldn't be speaking about this with you if Dennis hadn't given me the go ahead to share and let it be known. He has had some health problems in the past. But again, he is feeling better than ever now. Dennis will be back.

AAJ: Thanks for sharing such great and important news. He is a jazz fusion legend. Sure hope to see him behind his kit again soon.

DB: Well, Dennis and I are planning a tour in Europe with Hadrien and Eric Marienthal.

AAJ: Very nice. I would love to see and hear that quartet.

DB: That won't be until April of next year. We'll see how it goes, and then maybe book a few shows here in the USA. Hopefully Europe gets its shit together by then. I'm just hoping that when everyone has received the vaccine that things will turn quickly to a much more optimistic global positive reality.

AAJ: We all certainly have our fingers crossed for that to happen. Mentioning Mike Stern triggers the memory of his hand and shoulder injuries a few years ago. Am I correct that you subbed for him to complete a tour with Bill Evans?

DB: Not to finish it, to do the whole schedule. On like three days notice. Mike's accident happened like three days before the tour started.

AAJ: That had to be a challenging experience to jump into with no time to prepare.

DB: Yeah, I would say so (with a laugh). I was up for a couple of nights working on it (laughing harder). But it was fun and more importantly I was happy and honored to be able to help Mike out. And of course to help Bill out as well. Bill and I have been friends for a long time. He was my biggest champion in getting me my first record deal.

AAJ: Well, I know that Stern and Evans go all the way back to playing with Miles Davis together.

DB: Yeah, with Marcus Marcus Miller and Al Foster. What a band! Now was that before The Man With the Horn (Columbia, 1981)? I'm trying to get my chronology straight here.

AAJ: I believe The Man With the Horn was the first one Stern and Evans did with Miles. I know that Evans got the gig first and then got Stern an audition with Miles.

DB: Yeah and Bill got in through Dave Liebman. Miles was looking for a saxophonist and called Dave to see if he knew of someone. Of course, Liebman probably said, "Hey, what about me?"(laughing out loud) But Miles wanted all young guys. Bill also had a lot to do with bringing in John Scofield after Mike. Miles had known Al Foster for many years. Marcus was the hot young bassist in New York at the time.

AAJ: They, of course, ended up with a great connection, with Miller ultimately composing and producing for Miles.

DB: Yeah, later on. He produced the seminal recording Tutu (Warner Brothers, 1986).

AAJ: Well, getting back to you jumping in on that tour, you had long since played all the venues all over the world, from major jazz festivals to small clubs. So no surprises there. Do you prefer the intimacy of clubs like Ronnie Scott's or The Blue Note, or the energy brought forth at the big jazz festivals like Montreux or North Sea?

DB: They both have their appeal for an artist as a performer. If I absolutely had to pick one over the other I would pick the club. I like the feel of a club. The way you can feel the people.

AAJ: You can make more of a connection.

DB: Right, but also the people can make a better connection with the artist. You can actually feel individual energy in a club, as opposed to the big collective energy of a large venue. That's a giant wave of energy as opposed to these sort of laser beams. The energy helps you get to a place where you can give it everything you have.

AAJ: Are there a few venues around the world that you have a special affinity for? Whether it be the sound or the ambiance or whatever reason.

DB: Oh for sure. Actually the Baked Potato is one for sure. No doubt about that. I have had some nice experiences in New York at The Blue Note. The Blue Note is a showcase for the jazz elite from around the world. There used to be great club that was more New York-centric. Man, I can't think of its name right now. It was downtown and then It moved to midtown around Third Avenue. It was a cool vibe. In Europe places like New Morning in Paris for sure.

AAJ: I had a feeling you would mention that one.

DB: That's a really cool place. I love playing the A-Trane in Berlin. Small place with a really good vibe.

AAJ: Great name.

DB: Yeah and its spelled Trane, by the way.

AAJ: Even better.

DB: Yeah, yeah. There's a couple of clubs in Scandinavia that are cool, like Fasching in Stockholm and Nefertiti in Gothenburg. The Cotton Club in Japan. I love that place. They're all different. They all have their own unique vibe from different people and different cultures. All the counties have nice places to play. There is a place called Gaste Garage, which is in a small town in northwest Germany called Osnabruck. For us it's like a home away from home. The staff there is just fantastic. The other thing about Gaste Garage is that they only have few shows a year. The rest of the time it is a high performance unusual car repair shop.

AAJ: Interesting, so it really is a garage.

DB: Yeah, with lifts and everything. When they have a concert, you will see a couple of weird cars there, like a Delorean or whatever. It's always something that is kind of hard to get parts for or something like that. They'll have these cool cars up on the lifts. I love that place.

AAJ Well, that whole concept is cool.

DB: Yeah, it really is. I can only imagine that the people that go there to have their cars worked on are like, "why is there a stage with lights and everything on it over there in the corner?" (laughing out loud)

AAJ: Right! (laughing). You have to have seriously missed playing this past year plus, but for the most part you have been able to continue teaching. Maybe you could tell us about that aspect of your career.

DB: Sure, yeah, I would be happy to. I had been doing master classes and clinics for about ten years before we moved out west in 2005. The wonderful composer and guitarist Jeff Richman was teaching at what they then called the L.A. Music Academy back then and also at the Musician's Institute. I was doing some gigs in the area with Marcus and some other guys. Jeff suggested that if I had free afternoon that I should come over and do a clinic at the Academy, which I did. Then another time he asked me to do a clinic at M. I. So I did that and I met Beth Marlis, who was the head of the guitar department at the time. She enjoyed my clinic, and a short time later she called to see if I would be interested in teaching a couple of courses of my own choosing. An opportunity to teach with my own curriculum. I liked the idea of sort of paying forward some of the things that I have learned over the years. Particularly in the area of rhythm guitar. Getting into improvising and music philosophy as well. In 2008 I started teaching a jazz ensemble class and a class called advanced electric guitar scales. A really cool thing about M.I. is that they have this thing called open counseling. For an hour or two any student can come in to the studio and ask about and talk about anything they want to work on. Their reading skills, some rhythm guitar stuff, improvising, or maybe wanting to learn a different way to voice chords, tone, or anything they want. This is a free class with tuition. You could spend ten hours a week doing it and get just as much of an education as with your curriculum classes.

AAJ: Absolutely, because they choose what they want to work on. Very cool.

DB: Not only what to talk about, but who you want to hear it from. One day it could be Scott Henderson, another day it's me, another day its Allen Hinds or Sid Jacobs, or another of the many great guitarists that have taught there. It, of course, is the same deal for other instruments—drums, bass, etc. So, anyways, I am still teaching there.

AAJ: Thirteen years and counting. When you tell a student to "remove the noise," what do you mean by that?

DB: Ahhhh, yes, yes, yes, I'm glad you brought that up. That's about ego. What I'm referring to is distractions. I call those distractions noise. One of the biggest distractions is when you think that something you played isn't good, or that it's great. Because now you are thinking of what you just did, instead of what is ahead of you. There's nothing you can do about it. Once you've played whatever you played you can't take it back. It's over. Instead you need to worry about the immediate future. Think about the next note or the next phrase. Focus your being on that. Focus on the seven elements of music. Those are subjective, but I'm talking about melody, harmony, rhythm, dynamics. The brilliant keyboard player Bernard Wright kind of quantified the other three, which are tone, concept, and purpose. You have these seven elements of music that you have to consider with every note you play or don't play. If you're a dog and you see a squirrel you turn your head.

AAJ: Squirrel!

DB: Yes, you are easily distracted. So if you are thinking about what someone else just played, or what you just played, then you are being distracted. What you think about your playing is not important. What I think of your playing is also not important. What you might think that I am thinking or speculating about your playing is also not important. What you think an audience thought of your playing is also not important. All of those thing are noise that distract from thinking about these very important seven elements. These are the things that are required for music to sound good and feel good. The manifestation that occurs is that you aren't thinking at all and you instead are in a mindset I call the flow. You know, everybody's human. Everybody has an ego. I think it takes a certain amount of ego to have the confidence to get up on a stage and play or turn the red light on a recording device. But we have to remind ourselves that we are there to serve the music. Anything else we might think about is going to be detrimental at that time. At the moment of actual creation.

AAJ: You really need to be present in the moment.

DB: Yes, you need to be present. That's a good way of putting it. You can't be in two places at once. I hope that all makes sense and answered your question.

AAJ: Very much so. In fact, I appreciate the depth of your response. Another thing I wanted to ask you about was influences. I have yet to speak to a fusion guitarist that doesn't sight Jimi Hendrix. That's kind of a no brainer. I can't even imagine though what it must have been like to see him in concert when I was twelve years old. Maybe you can help me imagine. Where did you see him? What do you remember about the experience?

DB: It was at the Statler Hilton (now known as The Capital Hilton) in Washington D.C. I don't know if that place even still exists. At the time my dad was in Viet Nam. I remember this poster that said Jimi Hendrix Are You Experienced? That's all it said other than the location, the date and time and ticket prices.

AAJ: We are all long since familiar with Are You Experienced (Track, 1967), but I'm guessing at the time you had no idea what that meant.

DB: That's exactly right. I was just barely getting into music. My parents had bought me a Sears electric guitar, with lipstick pickups. It was the one where the amp was the case. You know, you open up the case and stand it up and it was your amp and speaker. It was a tube amp. Some friends that were a little bit older than me were saying that I just had to go see this guy Jimi Hendrix. The way they were talking about him I didn't know what he was. I thought maybe he was some kind of a magician or something. A high wire act, something mystical, or transcendental meditation or who knows. I went to the show not knowing anything of what to expect. Then, man, I don't know how to even explain it.

AAJ: Well, it had to be mind blowing.

DB: It was terrifying. I thought guitar was like playing campfire chords or some little love songs or maybe a kind of folky protest song. To hear the power coming off that stage with only three guys up there was absolutely terrifying.

AAJ: Hopefully not so terrorizing that you weren't able to enjoy it.

DB: I was completely mesmerized. It was exhilarating. But sort of in a 'I'm doing something that's dangerous.' It was really fun, but it felt dangerous. It didn't feel like it was safe. Maybe it felt like sky diving or something. I don't know if that is exactly it, but it felt scary in a good way.

AAJ: It clearly was enthralling and obviously changed your entire perspective of the guitar.

DB: It did, yeah. After that I spent hours upon hours upon hours trying to figure out what he was doing on the guitar. That was made even more difficult by the fact that Jimi played left-handed. He reversed the strings so that the lowest strings were on the top just like a conventional right handed guitar. Some other great left-handed players don't reverse the strings and just play it that way. Guys like Albert King and a great guitarist out of Boston named Jeff Lockhart . Then of course one the greatest guitarists since Jimi Hendrix, in my mind, is Eric Gales.

AAJ: Yeah, some bass players as well. Jimmy Haslip plays left-handed upside down as well.

DB: Yeah that would be right that Jimmy does that. So does another fine bassist out of Texas named Chris Walker. But as I say, Jimi didn't do it that way. He had the strings reversed. The spirit of his playing and his relationship with acoustic blues has always stayed with me. His approach to rhythms and melodies has always subconsciously been with me. His acoustic sort of Delta blues approach has imprinted that sort of gray area between my melodic and rhythmic soloing. I don't consider myself to be a blues player or a blues aficionado, but through Hendrix and subsequently listening to the electric guys like the Kings (Albert, Freddie King and B.B. King), and Albert Collins, I get it and I feel it. I don't play a lot of blues licks per se, or have a giant classic blues repertoire in my lexicon. But you know, I hear it in John Coltrane even though he isn't playing blues licks. There is that emotionally driven expression.

AAJ: After Hendrix the responses start to vary. In your case, most interestingly, Johnny Winter. He, no doubt, really smoked and always had a really powerful groove. I only got to see him play just one memorable time. What is it about Winter's music and style of play that really reaches you?

DB: He was incredibly articulate. He had blazing technique and speed with all that feel. To play with that kind of feel and that speed and level of technique was just amazing. Johnny Winter had the chops. His chops were amazing and somehow he had so much feel in his phrasing. To be able to execute at this mind boggling level was unbelievable. I liked his singing too. I always thought he was an excellent blues singer. Also his slide guitar playing is on par with any of the greatest slide players of all time in my opinion. His acoustic dobro playing was incredible. You know that song "Dallas" from the album Johnny Winter(Columbia, 1969)?

Tags

SoCal Jazz

Dean Brown

Jim Worsley

United States

California

San Diego

Miles Davis

Larry Coryell

john mclaughlin

Billy Cobham

David Sanborn

Steve Smith

Marvin "Smitty" Smith

Jerry Etkins

Ernest Tibbs

Branford Marsalis

Jeff "Tain" Watts

Kevin Eubanks

Dave Carpenter

Peter Erskine

George Duke

Tower of Power

Cold Blood

Jimmy Earl

Hadrien Feraud

Anthony Jackson

Hiromi

Simon Phillips

Dennis Chambers

Bobby Sparks

Snarky Puppy

Roy Hargrove

Brandon Fields

Will Lee

Protocol

Jeff Babko

Everette Harp

Greg Howe

Andy Timmons

Alphonso Johnson

Tom Brechtlein

Vinnie Colaiuta

Herbie Hancock

jeff beck

Tim Landers

Kirk Whalum

Bob James

Larry Carlton

Lee Ritenour

Robben Ford

The Brecker Brothers

Vital Information

Journey

Dave Wilczewski

Mike Stern

Hiram Bullock

Jimmy Johnson

James Taylor

Steve Gadd

Michael Landau

Allan Holdsworth

Santana

John Scofield

Eric Marienthal

Marcus Miller

Al Foster

Dave Liebman

Jeff Richman

Scott Henderson

Allan Hinds

Sid Jacobs

Bernard Wright

Jimi Hendrix

albert king

Jeff Lockhart

Eric Gales

Jimmy Haslip

Chris Walker

Freddie King

BB King

Albert Collins

John Coltrane

Johnny Winter

Edgar Winter

Tommy Dorsey

Fred Waring

Keith Carlock

randy brecker

Mino Cinelu

Jim Beard

steely dan

Devron Patterson

Don Patterson

Roberta Flack

Nina Simone

Jonathan Butler

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.