Home » Jazz Articles » Under the Radar » Women in Jazz, Pt. 2: The Girls From Piney Woods

Women in Jazz, Pt. 2: The Girls From Piney Woods

The musicians wanted permission to go backstage and see what boy’s band was back there playing, see how this thing was done. ‘It was pantomime, they got to have a band back there,’ they said. ‘Ain't no girls can play like that.’

—Eddie Durham

One hundred years after Lil Hardin Armstrong held the ladder for Louis Armstrong, saxophonist Tia Fuller provides a window into how little things have changed for women in jazz. The composer and professor at Berklee College of Music has been a member of Beyoncé Knowles all-female touring band and has recorded with Esperanza Spalding, Dianne Reeves, and Geri Allen. She has released five jazz albums as a leader; the most recent Diamond Cut (Mack Avenue Records, 2018) features Dave Holland, guitarist Adam Rogers, drummers Bill Stewart, Jack DeJohnette, and Terri Lyne Carrington who also produced the album. Diamond Cut was nominated for the 2019 Best Jazz Instrumental Album Grammy in a category that included Fred Hersch, Brad Mehldau, Joshua Redman, and Wayne Shorter.

On the day of the awards Fuller wrote an opinion piece 2019 Grammy Awards: Why I'm Using My Nomination to Speak Out About Sexism in the World of Jazz, for NBC (www.nbc.com, February 10, 2019). Fuller emphasizes the obvious slights while putting a face on the discrimination and sexism she has personally experienced. The examples are nuanced but they are actions reserved for the "other," the outsider. She talks of suggestions she should "smile more" when performing. It's unlikely anyone would have said that to Miles Davis. Fuller writes about comments made when she's spotted carrying her saxophone case such as "Do you really play that?" Ultimately, Fuller believes that that the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements have had a positive halo effect on women in jazz and elsewhere but she knows progress is painfully slow when she writes "Young girls can fly a rocket ship, throw a football and solo on the saxophone—but it is always harder to be what you cannot see."

International Sweethearts of Rhythm

The Swing Era that dominated the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s represented the only time in the history of jazz when the genre and "popular music" were synonymous. But, like all the stylistic periods of jazz, it was relatively short-lived. The music piggy-backed on the earlier dance band music of the 1920s and early 1930s and evolved to reflect the energetic rhythms and blues influences made popular by black territory bands. Like dance bands, swing was heavily reliant on dancehall venues but thanks to the growth and affordability of radio, swing survived the Great Depression and thrived into the post-World War II years.The rural, south-central Mississippi community of Piney Woods was established on land that had been the Choctaw Nation before their people's forced removal to Oklahoma. Known as an underdeveloped and lawless area, the Piney Woods were sparingly used by sheep and cattle herders but was not well-suited to agriculture. Representatives from Piney Woods voted to secede from the Confederacy in 1861 and launched guerilla-style attacks on the Southern troops. In retribution, the Confederate Army raided subsistence farmers and confiscated livestock, depleting the few resources in the community. The poor region in the poorest state in the U.S. became more impoverished as farmland opened to the north in Mississippi and the small population dwindled further. In 1938, near the end of the depression, the Piney Woods Country Life School opened. Despite the institution's idyllic name, it was an orphanage and school for poor black and white children. The Piney Woods School was an unlikely starting point for the most famous "all-girl" jazz band in jazz history.

Laurence Clifton Jones came from of family of educators and upon graduating from the University of Iowa in 1908 he was offered—but refused—an offer to teach at the prestigious Tuskegee Institute. Dr. Jones had a higher calling. Learning that Rankin County, Mississippi, had an eighty percent illiteracy rate, he started the Piney Woods School with two dollars and three students in a sheep shed on land donated to him by a freed slave. In 1912 Jones and his wife Grace, who had previously founded her own school, were given lumber from a white sawmill owner, food, money and more land from other donors. Grace Jones was a tireless fundraiser and a teacher at Piney Woods. The couple's dedication to educating their students became local legend, so much so that when a white lynch mob attempted to hang Jones (simply because he was black) in 1918, they relented because of his reputation. The famed author and motivational speaker Dale Carnegie reported that the lynch mob actually donated money to the school. The most effective fundraising tool that the school developed was an all-girl jazz orchestra whose performances brought in much-needed donations.

Dr. Jones and Grace Jones had originated several all-girl groups, some vocal and others instrumental. Probably called the Piney Woods School Band at their inception, the International Sweethearts of Rhythm were inspired by Jones' affinity for the Ina Ray Hutton's Melodears. Hutton was born Odessa Cowan in 1916, on Chicago's South Side in a predominantly black area. Census records indicate that she was black but she was perceived as being white as evidenced by her nickname, "the Blond Bombshell of Rhythm." Jazz promoter Irving Mills assembled an all-female band—the Melodears—changed Cowan's name and made her the band leader. Though she was only eighteen, she had won great reviews performing on Broadway at fourteen. She led the group through the 1930s touring regularly, appearing in films, and in 1950, on television with own Emmy-winning program. She recorded little, did very few interviews and her name faded into obscurity.

In an all-white Mississippi orphanage, a young girl's race was determined to be black and she was required to leave that facility. The Jones family took her in at Piney Woods and adopted Helen Jones, who became a member of the school's multiple musical fundraising groups -the Cotton Blossom Singers, the Swinging Rays of Rhythm, and, at age eleven, she played trombone in their International Sweethearts of Rhythm. Touring through much of the eastern U.S. the Sweethearts developed a significant following and in 1943 they severed ties with the Piney Woods school. In his book One O'clock Jump: The Unforgettable History of The Oklahoma City Blue Devils (Beacon Press, 2006), D.H. Daniels quotes the legendary black newspaper, the Chicago Defender reacting to the band's 1943 performance at Chicago's Regal Theater, writing it was "One of the hottest stage shows that ever raised the roof of the theater!" Over four-thousand fans waited in line for a show at the Palace Theater in Memphis, Tennessee and in 1945 they performed for African American troops on a six-month tour in France and Germany. Among their fans were Count Basie, Jimmy Lunceford, and Louis Armstrong. The group played to wildly enthusiastic audiences throughout the eastern black circuit and at top venues such as the Apollo, Savoy Ballroom and the Howard Theater in Washington D.C. Nevertheless, Sherrie Tucker reports in Swing Shift (Duke University Press, 2000), neither the white or black press typically emphasized their musical skills and instead wrote about their appearance, marital status, and similar lightweight topics. In their lifespan of 1937-1949, they were given the opportunity to record only five songs though their music was later covered on International Sweethearts of Rhythm: Hottest Women's Band of the 1940s (Rosetta Records, 1984). The first integrated all women's orchestra in the U.S. included "International" in the band's name because the personnel, while predominantly African American, included members from diverse and random heritages: African, European, and Puerto Rican descent. Alma Cortez was a Mexican clarinetist, Nina de La Cruz, an American Indian saxophonist and saxophonist Willie Mae Wong was of Chinese descent.

Some of the most prominent members of International Sweethearts of Rhythm joined the group, post-Piney Woods. Among them was the bandleader and vocalist Anna Mae Winburn, who was hired in 1941 and remained with the group until it's end. The Sweethearts refined their skills with the guidance of Eddie Durham who had played, composed and/or arranged for Benny Moten, Count Basie, Glenn Miller, and other top tier bandleaders of the time. In American Women in Jazz (Wideview Books, 1982) author Sally Plaksin details Durham's role in "polishing" the act for the big time. He often focused on presentation, not in the usual sexist manner, but a carefully choreographed twist that turned leering vulnerability into visual art. Plaskin describes Durham's optics around Nova Lee McGee, the Sweethearts' Hawaiian trumpet player: "When they come out, Nova Lee McGee plays the solo...and they blackened out all the stage...the five saxophones would move down to the front in the dark. You wouldn't know they were there." Despite the success of the dramatic effects and excellent musicianship, Durham found male patrons to be as skeptical as conspiracy theorists. "Then a lot of guys went to the box office and wanted to see Mr. Schiffman [the owner of the Apollo]. The musicians wanted permission to go backstage and see what boy's band was back there playing, see how this thing was done. 'It was pantomime, they got to have a band back there,' they said. 'Ain't no girls can play like that.'"

Among the most notable players in the Sweethearts was saxophonist Violet May "Vi" Burnside. Like Winburn, Burnside joined the band in 1941 and remained for the duration. She toured Europe with the Sweethearts' USO concerts during World War II and post-Sweethearts became a leader, fronting Vi Burnside's All-Girl Band and Vi Burnside's All-Stars into the 1960s. In 1953 she briefly reunited with Winburn playing in Harlem. Burnside later became an official in a Washington, D.C. musicians' union. Trumpeter Tiny Davis (Ernestine Carroll) joined the Sweethearts in the early 1940s and remained until 1947. Known as "Queen of the Trumpet," Davis was frequently compared to Louis Armstrong for her playing. Upon leaving the group she formed an ensemble called the Hell Divers, presumably based on a class of WWII fighter plane. Signed to the Decca Records label, the group toured into the early 1950s. Their bassist, Ruby Lucas, became Davis' life partner and the two opened Ruby's Gay Spot, in Chicago where Davis was active in music into the 1980s. Willie Mae Wong had never played the saxophone when she was recruited into the band but achieved stardom on the baritone.

Tiny Davis wasn't the first player in the Sweethearts to be dubbed "Queen." That honor went to the drummer who joined the group in 1939. Writing in The Philadelphia Inquirer in 1984, the noted critic Francis Davis observed the band was "Powered by Pauline Braddy's drumming..." Boston native and the Sweethearts' alto saxophonist Rosalind "Roz" Cron grew up in unanticipated ways while with the band. Joining while still in her teens, and being only the second white musician in the band, Cron experienced the discrimination that her bandmates lived with. She was arrested in Texas for breaching the segregation law that forbade racial mixing of bands but that incident only strengthened the bonds within the group. Cron, now in her nineties, recalled the Sweethearts breaking box-office records at the Howard Theater and audiences dancing in the aisles at the Apollo. The members of the Sweethearts have had incredible longevity: Helen Jones became a nurse and, like Cron, is in her nineties; drummer Viola Smith is still living at one-hundred-six. Cron, Davis, Burnside and several other members of the ensemble remained active in music following the demise of the band. In some cases, the musicians became part of spinoff groups. But, without a substantial discography, and with little insightful press coverage, the International Sweethearts of Rhythm faded from memory after the 1940s. They may have completely disappeared from jazz history were it not for Marian McPartland.

Marian McPartland

She was born in 1918, west of London in Slough, England but few artists were more a part of American jazz than pianist and long-time radio host, Marian McPartland (née Turner). Her mother, always mindful of the family's proper English social position, insisted on McPartland's playing the violin. However, at a very young age she began playing piano publicly; from grade school to vaudeville, she entertained World War II troops stationed in England. One of them was American clarinetist Jimmy McPartland, a pioneer in 1920s Chicago jazz whom she met while both were playing in Belgium. In 1945 they married and returned to the U.S. when the war ended. McPartland did not have an easy time establishing herself in the states. In New York, she sought out and befriended Mary Lou Williams whose early work in bebop was an inspiration to McPartland. But the pianist told NPR she was viewed as an oddity and earned insincere blandishments about being a good pianist "for a girl." The most damaging comments came from a source close to home.Composer, musician, producer, radio host and writer Leonard Feather was known as the "Dean" of jazz critics; in that role, he could have substantial influence over the success or failure of less-established artists. The London-born critic was not without his biases and a self-serving agenda. In the latter case Feather wrote breathlessly positive press releases and reviews for his own compositions and recordings, while insinuating a high degree of objectivity in his analysis. As to his biases, McPartland was on the receiving end of his blunt and dismissive attitude toward women in jazz. According to the journalist Matt Schudel (Washington Post, January 12, 2013) "For years, Marian McPartland was defined by an offhand comment that critic Leonard Feather made in the jazz magazine Down Beat in 1951. McPartland, wrote the British-born Feather, had 'three hopeless strikes against her: She was British, white and female.'"

McPartland's enthusiasm for the art was never dampened by unsubstantiated critique. She founded her own trio in 1951 and while working at The Embers club on 54th Street in Manhattan, she played with legends such as Roy Eldridge and Coleman Hawkins. A later trio with drummer Joe Morello, and bassist Bill Crow was her most enduring, staying together four years and being named "Small Group of the Year" by Metronome magazine in 1954. McPartland recorded for Capitol, Savoy, Concord and several other major jazz labels, issuing almost five-dozen albums not including the Piano Jazz series. She won a Grammy, Peabody and numerous honors, and was awarded nine honorary degrees. But it was her Piano Jazz radio program that made McPartland famous. That program hosted top jazz artists such as Bill Evans, Dizzy Gillespie, Lionel Hampton, Dave Brubeck, Paul Bley, Cecil Taylor, Keith Jarrett and Randy Weston, and cross-over artists, with more than passing interest in jazz, including Nellie McKay, Elvis Costello, Steely Dan, Norah Jones, and Bruce Hornsby. But McPartland's series also served as a platform for women artists. Among her guests were Mary Lou Williams, Ann Hampton Callaway, Alice Coltrane, JoAnne Brackeen, Anat Cohen, Renee Rosnes, Grace Kelly, Geri Allen, Esperanza Spalding, Diane Schuur, Myra Melford, Carla Bley, Marilyn Crispell, Regina Carter, Hiromi (Uehara), and Diana Krall. The series spawned a collection of more than thirty Piano Jazz recordings taken from those National Public Radio broadcasts from 1978 until 2011. Rebroadcasts continue in many U.S. markets today.

In 1977 Jazz radio producer Diane Gregg and singer Carol Comer hatched the idea for a Kansas City Women's Jazz Festival while returning to their homes in that city, after having attended The Wichita Jazz Festival. The festival debuted the following year, Gregg and Comer bringing in McPartland to perform and to recruit other women artists. Fortunately, McPartland was not one to burn bridges as the festival's emcee was none other than Leonard Feather. Feather had, by this time, come to appreciate McPartland's work and record other female artists as a producer. In 1980 McPartland, now a regular part of the festival's operations contacted the surviving members of The International Sweethearts of Rhythm to propose a festival reunion. Gregg and Comer made it known in advance that the Sweethearts, who had not played as unit in almost thirty years, were not invited to be put on display, or to perform, unless they wanted to jam. The invitation was meant only to honor their achievements, but to no one's surprise, many of the Sweethearts became musically involved, Pauline Braddy picking up the sticks for the first time in more than a decade. McPartland successfully enlisted Carline Ray, Evelyn McGee, Nancy Brown, Willie Mae Wong, Helen Saine, Roz Cron, Anna Mae Winburn and Jesse Stone. Stone—the only male besides Durham to be associated with the group—was their musical director for two years. He later wrote "Shake, Rattle and Roll" under a pseudonym. The earliest of the Kansas City Women's Jazz Festival's brought in many highly regarded artists including Mary Lou Williams and another major talent who had, for a time, walked away from performing, Melba Liston.

Melba Liston

In 1933, at the age of seven, Kansas City, Missouri native Melba Liston acquired her first trombone when a traveling music store passed through the city. Liston didn't play the instrument nor did she anticipate the difficulty of learning it, but the next year she was playing solo on local radio programs. Her family moved to Los Angeles where, at sixteen, she joined the Lincoln Theatre's orchestra. Ten years later Liston was playing with Gerald Wilson's orchestra where she remained for five years until the group dispersed. Wilson became Liston's de facto patron in that she met many influential names in jazz through their connection. Along with Wilson, Liston joined the short-lived Dizzy Gillespie's Big Band which for a time included John Coltrane and pianist John Lewis. Afterwards, Liston and Wilson stayed together backing Billie Holiday at the low point in the singer's career. Not only was Holiday in the throes of drug addiction but the band had moved into bebop and the further they ventured into the deep south, the chillier the reception to this new music. The audiences thinned out leaving the musicians with little in resources as the tour folded.Disillusioned, Liston gave up performing and took an administrative position with the Los Angeles Board of Education while continuing to write and arrange music and play small roles in several movies, including The Ten Commandments (Paramount, 1956). In 1956 Gillespie was recruited by U.S. State Department's Jazz Ambassadors program. He coaxed Liston back into music for tours of the Middle East and Asia and that experience set Liston off to most successful phase of her career. The following year she again joined Gillespie's band for a South American Jazz Ambassador tour, and—later that year—appeared with him at the Newport Jazz Festival. In 1958 Liston recorded Melba and Her 'Bones (Metrojazz, 1959), her only recording as a leader. She met pianist/composer Randy Weston that same year and that relationship led to a decades-long partnership and ten albums. In the 1960s she also worked with trumpeter Clark Terry and Charles Mingus. In the 1970s and 1980s Liston led a number of her own groups until 1985, when the first of several strokes forced her to stop performing. She continued to write arrange for Weston, Gillespie and others until her death. In April, 1999 Harvard University sponsored a concert to honor Weston and Liston for their work together. Due to poor health she could not attend but was given a recording of the concert. The following week, Liston passed away.

Change

Back to Tia Fuller. In 2019, and in the company of four well-known male Grammy nominees on major labels, the odds were stacked against her. The eighty-five-year-old legend, Wayne Shorter won the category to no one's surprise. Fuller goes on; touring, teaching and, presumably, recording. And for women in jazz, the struggle also goes on. The well-publicized 2017 interview of Robert Glasper on Ethan Iverson's blog descended into locker-room territory with Glasper's blatantly sexist comments and Iverson's lack of pushback. Iverson's later self-defense couldn't mask that he had interviewed dozens of jazz musicians for his blog, none of whom were women. The fight for gender equality in jazz has been largely left up to women and so a group called We Have Voice was formed to promote women's rights in the arts. The members are almost all from the jazz community and include bassist Linda May Han Oh, Jen Shyu, vocalist Sara Serpa, saxophonist María Grand, and Terri Lyne Carrington. The organization's broad goals include the prevention of harassment, self-preservation and promotion, and codes aimed at advancing women's artistic careers. We Have Voice is not the first organization set up with the purpose of supporting women in jazz. Almost one-hundred years ago Olivia Porter Shipp—a New Orleans bassist and bandleader—set up the Negro Women's Orchestral and Civic Association to help create opportunities for women musicians. Change is slow.Selected Discography

Hot Licks: 1944-1946 The International Sweethearts of Rhythm

Hot Licks: 1944-1946 The International Sweethearts of Rhythm (Rosetta, 1984)

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm recorded only four or five sides in the studio but their World War II performances on the Armed Forces Radio Service were captured on reel-to-reel tape. The second-wave of the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s rekindled an interest in the group but not until 1984 did the Rosetta label release Hot Licks: 1944-1946: The International Sweethearts of Rhythm, a vinyl collection of sixteen songs. The quality of the radio selections is spotty but it's all quite listenable. More important, the collection demonstrates with certainty that the Sweethearts were not a novelty band but a hard-charging swing ensemble. Several CD and digital versions of the album were released on different labels in the 2000s. Some of the same tunes appear on a release, Jubilee Sessions by Big Band Jazz Jubilee Sessions (Hindsight, 2013) featuring a variety of artists.

Marian McPartland: Piano Jazz with Mary Lou Williams

Marian McPartland: Piano Jazz with Mary Lou Williams (Concord, 2004)

McPartland's Piano Jazz series typically featured the host and her guest alone; an intimate setting with just enough discussion to be enlightening. Apparently unplanned, McPartland's old friend Mary Lou Williams was invited as the program's guest but arrived with bassist Ronnie Boykins for the first release of the long-running series. A bit rough around the edges at times, it adds—in retrospect—a certain charm to the program. Recorded in 1978, it was not released until 2004. Boykins and Williams engage in a bit of distracting set direction early on but the always-composed McPartland pulls the program together, playfully coaxing Williams into "Rosa Mae" and a subsequent bit of vocalizing. The two pianists even wander into avant-garde territory with "Baby Man" and devote a good portion of time to the blues including "Scratchin' in the Gravel," played on tandem pianos.

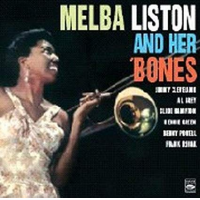

Melba Liston and Her 'Bones

Melba Liston and Her 'Bones(Metrojazz, 1959)

Melba Liston's work as an arranger and composer overshadowed her brilliant trombone playing. Joined here by six other trombonists (seven, on the later CD reissues with bonus tracks), it takes some effort to isolate Liston's solos but having done so, her lyrical improvisations stand out. Players rotate through these compositions—four are Liston originals—and include Slide Hampton playing both trombone and tuba, Ray Bryant on piano, and guitarist Kenny Burrell.

Credits

- NBC News Tia Fuller

- Mississippi Encyclopedia

- Swing Shift: All-Girl Bands of the 1940s; Sherrie Tucker (Duke University Press, 2000)

- The Philadelphia Inquirer 14 Dec 1984, Page 110

- Washington Post, Matt Schudel, January 12, 2013

- New York Times, ( John S. Wilson, March 16, 1978

- Black Women in American Bands and Orchestras; D. Antoinette Handy (Scarecrow Press, 1998)

- American Women in Jazz; Sally Plackson (Wideview Books, 1982)

- One O'clock Jump: The Unforgettable History of The Oklahoma City Blue Devils; D.H. Daniels (Beacon Press, 2006)

Tags

Under the Radar

Karl Ackermann

Lil Hardin

Louis Armstrong

Tia Fuller

Esperanza Spalding

Dianne Reeves

Geri Allen

Dave Holland

Adam Rogers

Bill Stewart

Jack DeJohnette

Terri Lyne Carrington

Fred Hersch

brad mehldau

Joshua Redman

Wayne Shorter

Miles Davis

Count Basie

Jimmy Lunceford

Eddie Durham

Benny Moten

Glenn Miller

Marian McPartland

Mary Lou Williams

Roy Eldridge

Coleman Hawkins

Bill Evans

Dizzy Gillespie

Lionel Hampton

Dave Brubeck

Paul Bley

Cecil Taylor

Keith Jarrett

Randy Weston

Nellie McKay

Elvis Costello

steely dan

Norah Jones

Bruce Hornsby

Alice Coltrane

Joanne Brackeen

Anat Cohen

Renee Rosnes

grace kelly

Diane Schurr

Myra Melford

carla bley

Marilyn Crispell

Regina Carter

Hiromi

Diana Krall

Melba Liston

Gerald Wilson

John Coltrane

John Lewis

Billie Holiday

Clark Terry

Charles Mingus

Robert Glasper

Ethan Iverson

Linda Oh

Ronnie Boykins

Slide Hampton

Ray Bryant

Kenny Burrell

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Tia Fuller Concerts

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.