Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Philly Joe Jones Biography: The Life and Legacy of a Dru...

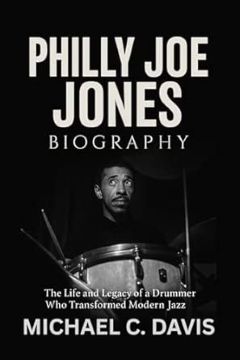

Philly Joe Jones Biography: The Life and Legacy of a Drummer Who Transformed Modern Jazz

Philly Joe Jones Biography: The Life and Legacy of a Drummer Who Transformed Modern JazzMichael C. Davis140 pagesISBN: #9798269455297Self Published2025

Philly Joe Jones Biography: The Life and Legacy of a Drummer Who Transformed Modern JazzMichael C. Davis140 pagesISBN: #9798269455297Self Published2025 Anyone who is seeking out anecdotes about Philly Joe Jones's relationships with a veritable who's who of jazz greats, or particulars of his life off the bandstand, might want to steer clear of Michael C. Davis's biography of the celebrated drummer, bandleader, mentor, and teacher. Employing a streamlined approach (130 pages of text; no quotes, references, endnotes, or discography), Davis concentrates on Jones's musical goals and values, and the nuts and bolts of his methods. Without employing a surfeit of music terms and concepts, he artfully describes the sound of his subject's drumming and its relationship to the music of Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Bill Evans, Cannonball Adderley, Dexter Gordon, and other significant figures. All along, Davis deftly integrates the ups and downs of Jones's career in the context of the apex and the decline of modern jazz in American popular culture during the mid-to-late twentieth century.

Jones's evolution from a child banging out rhythms on household surfaces to a first-call drummer in the fertile Philadelphia jazz scene in his late teens, is among the most captivating aspects of the book. Davis constructs a riveting account of the drummer's innate talent and insatiable curiosity. He emphasizes that, for Jones, "rhythm was not just a musical element; it was a way of understanding and interacting with the world."

The street culture of Jones's working-class neighborhood was a never-ending source of stimulation; sounds ranged from "children playing, vendors calling out, and musicians performing on corners or in small bars." Jones imitated all of them on "tables, walls, or tin cans" long before acquiring a drum kit. No matter how sophisticated his playing would eventually become, in terms of technique, resonance with traditional jazz practices, and the ability to enhance any size ensemble, he never abandoned the edgy, high-energy, and spontaneous quality of the street sounds.

Jones's childhood and adolescence were filled with learning experiences that contributed to his eventual emergence as an influential jazz musician. In short, he was a sponge and an autodidact who pursued mastery of drumming mechanics and a sophisticated understanding of the ins and outs of jazz performance. He initiated a lifelong commitment to the practice of the standard drum rudiments that was more ambitious than a simple desire for greater stick control. In keeping with a goal of making rudiments sound "musical, fluid, and alive," he gradually converted them into "tools for creative expression." The same intent applied to the development of complex hand and foot exercises. Tap dancing lessons provided another dimension of coordination and training "in syncopation and timing."

An early interest in playing the piano comprised one aspect of Jones's nascent notions of "how the drums interacted with melody and structure within a band." Another was the avid listening to live radio broadcasts during the heyday of the swing, big band era, which gave him insights into the character and structure of the music of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and other prominent bandleaders. Thus began his conception of himself as an ensemble artist rather than a merely drum-centered musical identity. He endeavored to comprehend "the full picture of the music, not just his part." In particular, while paying close attention to the drumming of Jo Jones, Chick Webb, and Gene Krupa, he sought to understand how they complemented the rhythm, brass, and reed sections. Even as Jones embraced modern jazz and assimilated the innovations of Kenny Clarke and Max Roach, the "discipline and rhythmic clarity of swing" constituted the bedrock of his style.

Philadelphia in the 1930s and 1940s offered an abundance of stimulating, well-executed jazz in clubs, bars, community centers, dance halls, theatres, and other venues. Amidst creative ferment and the motivation induced by stiff competition, there were ample employment opportunities for capable musicians. In his youth, Jones often snuck in or stood outside of clubs within earshot to study "how the drummers interacted with soloists, how they built excitement, and how they commanded the flow of the music." ) Eventually, elder musicians offered advice and encouragement to the talented and eager tyro, including teaching him the all-important skill of reading and interpreting jazz charts. Before long, he was allowed to sit in on jam sessions. The do-or-die demands of jamming in fast company, Davis notes, "taught him more than any formal lesson could." Among other things, Jones quickly learned the importance of versatility; regardless of his stylistic preferences, it was imperative to embrace and master the blues, swing, and bebop, as well as to keep things moving on the dance floor.

While still in his teens, Jones treated every performance—dance music with large and small ensembles, adventurous bop-oriented combos, accompanying vocalists, jam sessions, and more—as an opportunity to learn and grow. No gig was taken for granted. Jones gained the respect of elder and younger players alike for professionalism, preparedness, and a willingness to adapt to every situation.

By the time Jones reached his peak on the Philadelphia jazz scene, working "almost constantly, moving from club to club, from one project to another" , he was well into establishing an extensive set of principles that remained intact for the rest of his career. First and foremost, he regarded jazz as "a living, breathing art form—one that requires constant renewal and honest expression." The pursuit of improvement is a lifelong endeavor; there is no endpoint. He worked assiduously to develop his own voice within the tradition, fusing a swing-era feel and bebop approaches, and shunned facile virtuosity. In his view, creativity was based on discipline—an intense, ongoing study of the instrument and its potential, listening to and absorbing the efforts of other drummers, and integrating what he learned into the realities of jazz performance.

In Jones's estimation, rhythm is "not just a backdrop but a voice—one that can speak as clearly and powerfully as any other in the ensemble." He understood that placing the drums on an equal footing with other instruments was a huge responsibility and, at the same time, believed that listening closely to and supporting others was as important as asserting oneself. He regarded the drums as a rhythmic tool, a means of storytelling, and capable of enhancing existing melodies and creating new ones, however brief, by means of phrases, fills, and judiciously placed accents. And Jones accepted that playing jazz at a high level entailed dealing with intense competition and working in high-pressure situations.

Davis encapsulates Jones's mature drumming style as a "balance of fire and finesse" and "discipline with daring" . His playing was "sharp, dynamic, and full of personality. He could swing with authority, but he also possessed an extraordinary sense of drama and timing." Jones's impressive technique was never unmindful of or distanced from the music; even during knotty combinations of hits that wowed audiences, every stroke had a meaning and a purpose. Ultimately, he created an equilibrium between "order and freedom" (p. 120), and encouraged musicians to feel "anchored by his pulse yet liberated by his responsiveness."

Jones's move to New York City in the late 1940s marked the beginning of decades of musical triumphs and widespread recognition as an influential jazz drumming stylist in the bop and hard bop genres. In an environment that included innovators such as Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, and Thelonious Monk, he quickly "realized that every performance was an audition." . Making a positive impression was essential to avoid getting thrown into the scrap heap of unemployed jazz drummers. Meeting the demands of a jazz scene in which there was always something happening, day and night, moving quickly from one gig, rehearsal, or jam session to another, necessitated "physical stamina and mental alertness" and required him to absorb the intricacies of bebop at its finest on the fly. He landed high-profile gigs with Tadd Dameron, Dexter Gordon, and Fats Navarro, and eventually joined trumpeter Miles Davis's first great quintet, which included tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, pianist Red Garland, and bassist Paul Chambers.

Davis's commentary on Jones's tailor-made ways of playing with each member of Miles Davis's group offers insight into the drummer's remarkable capacity to listen, respond, and initiate. In relation to Davis's trumpet, he "created tension and release, shaping the space around Miles's phrases so that every note landed with maximum impact." While he executed complex rhythmic figures amidst Chambers' firm foundation, they "produced a groove that was both elastic and driving, allowing the music to breathe while maintaining a constant pulse." Jones maintained a deeply conversational relationship with Garland. "When Garland played block chords or crisp runs, Jones would respond with perfectly placed cymbal hits or snare drum commentary." John Coltrane's long, searching lines "demanded a drummer who could provide both structure and propulsion." Jones matched his "intensity without overwhelming him."

In the 1960s, jazz continued to flourish artistically yet fell into a diminished position within popular culture and the marketplace. Audiences turned away from the music and avidly consumed more easily accessible sounds. Encouraged by a mass media always on the lookout for something new, many listeners gravitated to rock, Motown, and r &b. bop, hard bop, and other styles were left by the wayside, as old hat, excessively technical, and intellectual. Many venues that booked jazz either folded or changed formats; record companies reduced their jazz releases or dropped the music altogether; and the selection of jazz records on the shelves of retail stores shrank.

These changes resulted in a drastic reduction in employment opportunities for jazz musicians. Even prominent bandleaders had difficulty finding steady work. Jones was not an exception. Not only was he unable to sustain small bands of his own, but he also found it increasingly difficult to make a living in the United States as a sideman playing his brand of jazz. Nevertheless, he refused to compromise his standards and belief in swinging, straight-ahead, small-group sounds. As the decade progressed, he turned to Europe, at first on a part-time basis, and then established ongoing residences in London and Paris in the late 1960s and early 1970s. While these activities abroad did not cure his financial woes, at least he was welcomed and recognized as an important jazz musician. He found some work with talented, eager—to—learn young players as well as his fellow expatriates. Moreover, Jones translated years of mentoring drummers in the finer points of the instrument and jazz performance into part-time employment as a private teacher and clinician.

In the early 1970s, Jones returned to the United States and settled in New York. While the public's cognizance of jazz still paled in comparison to the popular music genres of the day, there was a marked increase in interest in the "rhythmic sophistication and expressive swing" that was his forte. Jones was able to make a living between appearances in small clubs, touring, record dates, and workshops, and produced a number of highly regarded recordings as a leader. In the early 1980s, a few years before his death, Jones founded and sustained a group named Dameronia, "an act of homage and renewal" of the music of his colleague, the late Tadd Dameron.

While Jones holds a prominent place in many written accounts of jazz in the second half of the twentieth century, it is nonetheless gratifying to read a book—length treatment that delves deeply into what really matters. Davis's text is noteworthy in its absence of stories of the drummer's extramusical activities, which in many versions of Jones's life often detract from his accomplishments. The author does a commendable job of explaining Jones's evolution and strengths as a musician in straightforward, substantive terms. He spends the last pages restating Jones's virtues as a player and uses them as a segue into his influence on modern jazz and eminent drummers ranging from Elvin Jones to Brian Blade. The book might have benefited from additional sources to support its claims of Jones's titanic impact. Apart from this reservation, Philly Joe Jones Biography: The Life and Legacy of a Drummer Who Transformed Modern Jazz is recommended to drummers of all kinds, jazz aficionados, and casual fans.

Tags

Book Review

David A. Orthmann

Self Published

Philly Joe Jones

Miles Davis

Sonny Rollins

Bill Evans

Cannonball Adderley

Dexter Gordon

duke ellington

Count Basie

Jo Jones

Chick Webb

Gene Krupa

Kenny Clarke

Max Roach

Charlie Parker

Bud Powell

Thelonious Monk

Tadd Dameron

Fats Navarro

John Coltrane

Red Garland

Paul Chambers

Dameronia

Elvin Jones

Brian Blade

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.