Home » Jazz Articles » In Pictures » Reimagining Bitches Brew at the New York City Winter Jazzfest

Reimagining Bitches Brew at the New York City Winter Jazzfest

This photo essay is not intended as a review, but rather as a reflection on my impressions and experience, conveyed through text and images.

Miles Davis' Bitches Brew (Sony Records, 1970) stands as one of the most consequential albums in the history of jazz. Upon its release in 1970, the record was met with a wide range of reactions, puzzling some critics while alienating others. Over time, however, it has come to be widely recognized as a masterpiece. More than a stylistic departure, "Bitches Brew" marked a decisive rupture with prevailing jazz conventions and helped usher in a new era of jazz-fusion, one whose impact extended well beyond jazz into rock, funk, electronic music, and experimental traditions.

The event began with an insightful interview with drummer Lenny White, conducted by trumpeter Adam O'Farrill. White played on the "Bitches Brew" sessions as a 19-year-old relative newcomer, having previously worked with Jackie McLean. Several of McLean's drummers, including Jack DeJohnette and Tony Williams, had already "graduated" to playing with Miles.

As was often the case, Miles offered minimal or cryptic guidance. White recalled being told to "play salt," a metaphor whose meaning was not immediately clear. There were two drummers on the original sessions—the other being DeJohnette—along with two percussionists, Don Alias and Juma Santos. Both DeJohnette and White were devoted admirers of Tony Williams, who had been the engine behind much of Miles' seminal 1960s work. However, when they attempted to emulate him, Miles stopped them, making it clear that was not what he wanted. White noted that Miles had been listening closely to Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, and Sly Stone, drawing inspiration from their elastic rhythmic concepts. His own goal, White explained, was for the percussion section to sound like a single drummer with eight arms. The striking cover art and album title were also discussed, with White remarking that Miles had "big cojones" to take such a risk. Altogether, the interview provided illuminating context for the music that followed.

I first heard "Bitches Brew" in my late teen years, sometime after its release. I was already familiar with In a Silent Way (Sony Records, 1970), another landmark recording that charted new directions in electric jazz and remains my favorite Miles album to this day. "Bitches Brew," however, took those ideas much further, expanding them into a denser, more turbulent sound shaped by rhythm, collective interplay, and the studio itself. It mystified me at first with its seemingly chaotic surface and elusive melodies, but over time, I came to understand and love the album. This mirrored my experience at this event, where what initially registered as chaos gradually resolved into something purposeful, immersive, and deeply satisfying.

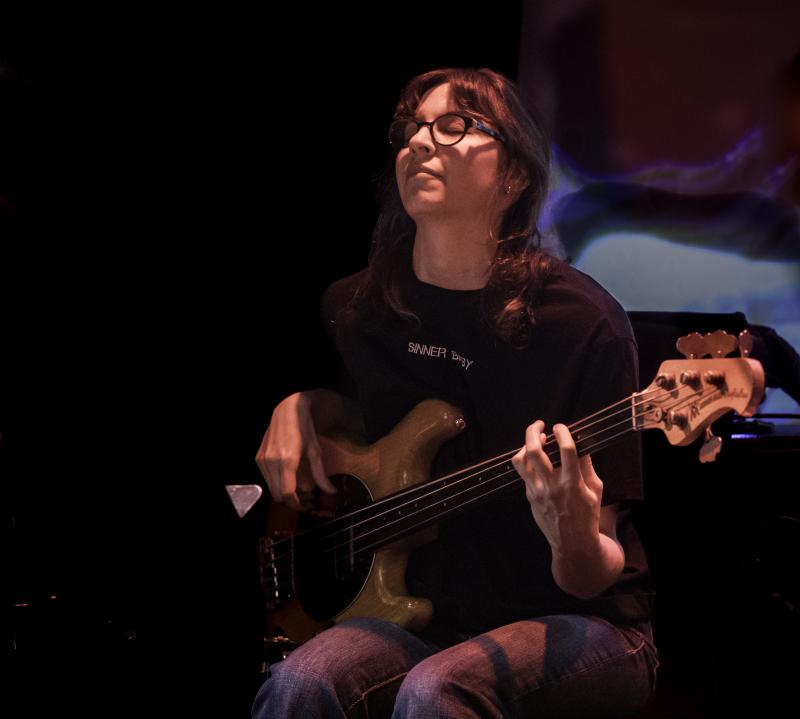

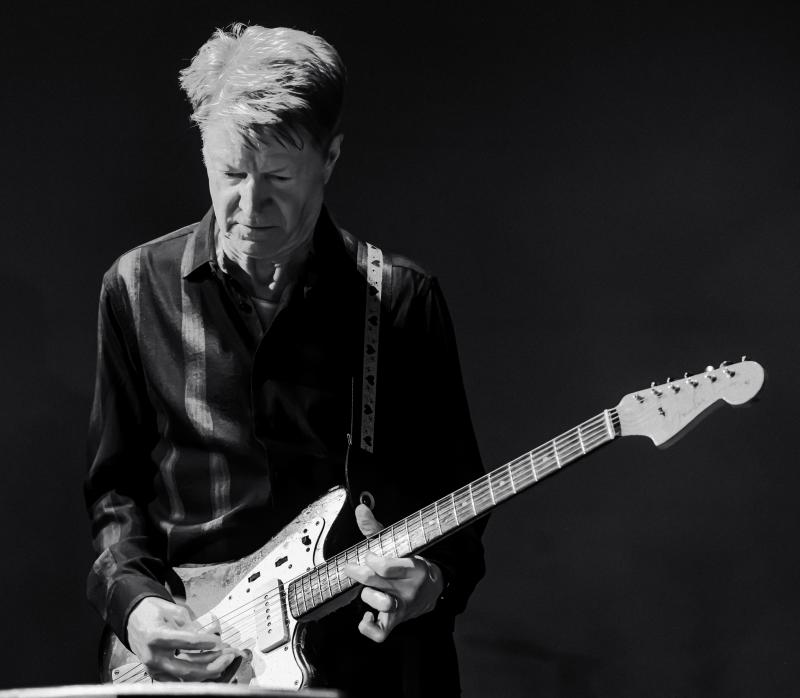

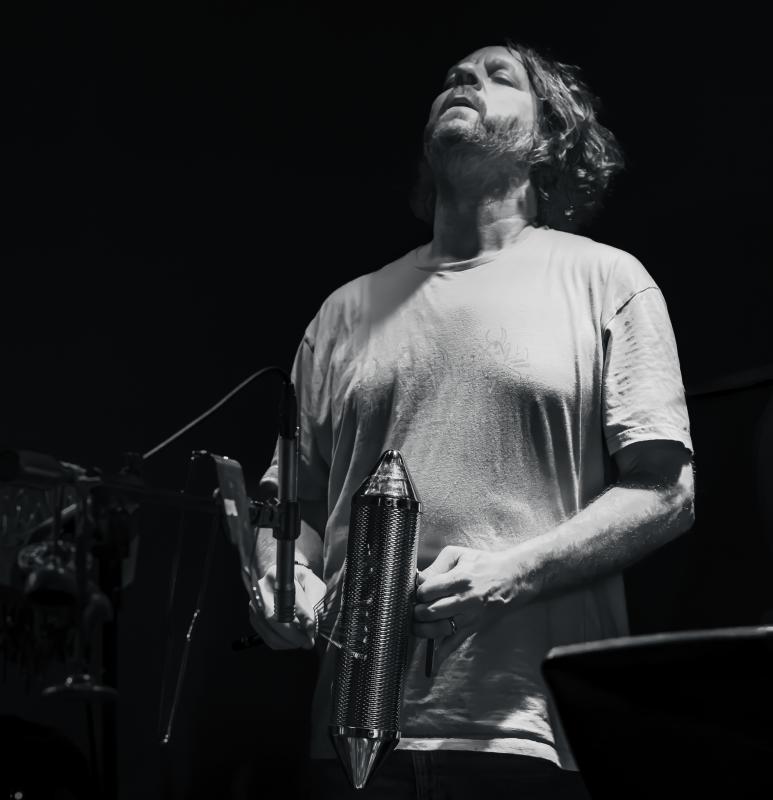

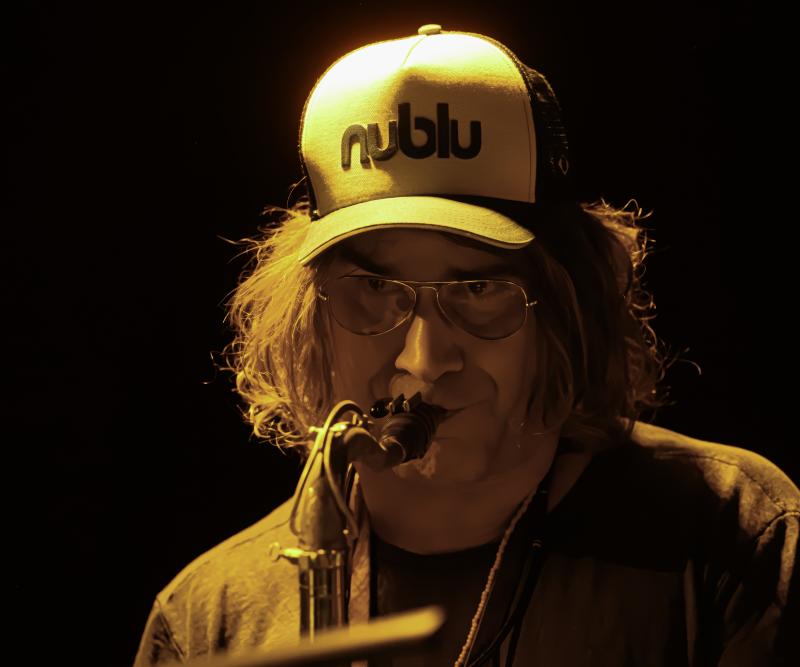

The "Bitches Brew Reimagined" ensemble featured a large, rhythm-forward lineup anchored by Nels Cline and Grey McMurray on guitars, with Yuka C. Honda handling keys and electronics alongside Stuart Bogie on bass clarinet. The reed section was further expanded by saxophonists Ilhan Ersahin and Alfredo Colón, the latter also playing EWI. The low end was supplied by bassist Anna Abondolo, while the expansive rhythmic foundation drew on a three-person drum and percussion configuration, with Tcheser Holmes on drums and Billy Martin and Kenny Wollesen on percussion. Shahzad Ismaily played synthesizers and added additional percussion. Bogie also served as conductor, replacing Dave Harrington, who had a family matter to attend to.

Miles's trumpet sound was central to the identity of the original album; he was a powerful presence. The absence of trumpet here was striking and made a powerful statement in its own right. In an interview posted on Pique-Nique's Instagram page, Stuart Bogie articulated a clear and considered vision. He first commented on Miles' role at the center of the original recording: "When Miles plays on "Bitches Brew," the ensemble spreads and the sound waves out, and he comes right into the center. It's striking how much his sound and presence commanded, and how much the musicians around him offered that space to him."

He then contrasted that approach with the objectives of this reimagined version: "We are taking away many of the sonic earmarks of the record because we don't want an impersonation. That music is about reactivity and deep listening—you can't write it down. It's not about the map, it's about being in the territory and what happens between us onstage."

In this conception, musical direction is deliberately decentralized, with the emphasis placed on process and not reproduction. Rather than attempting to recreate Miles's gravitational presence at the center of the music, the ensemble treats "Bitches Brew" as a point of departure, allowing form to emerge through collective listening and real-time interaction.

In a 2010 interview with Ashley Kahn, available on the Miles Davis website, Lenny White recalled that "we were all positioned in a semi-circle with Miles and Wayne in the middle. Miles would start a take by pointing at someone, like John or Jack, we'd all play, and then he'd stop us with a wave of his hand." The reimagined edition adopted a similar physical arrangement, with the ensemble positioned in a semicircle on the expansive LPR stage, with the center left open. A projected image of the cover artwork provided a striking backdrop, its vivid light sharply illuminating the dark stage and lending the scene an air of mystery and intrigue. Throughout the performance, Bogie intermittently conducted using a vocabulary of gestures and hand signals that functioned as a loose navigational framework rather than a fixed score. As with Miles, Bogie guided the ensemble through cues suggesting entrances, exits, and shifts in direction, allowing the music to unfold through collective responsiveness rather than predetermined form.

At first, the dense music felt as if multiple sound centers were operating at once. Each musician or subgroup seemed to inhabit its own space, creating several simultaneous points of focus rather than a single guiding thread. As a listener, I could choose to follow the electronics, the percussion, a horn line, or the guitar sounds, but none was clearly privileged over the others, resulting in a sense of competing attention and, at moments, perceived cacophony. They opened with an extended version of the album's title track, and over time the music began to cohere in my mind as the disparate elements aligned and the performance took on a discernible shape.

Tcheser Holmes is a drummer with a deep pocket. Even as the pulse continually shifted, he would locate a groove and hold it, allowing the other percussionists to align around him. That grounding presence gave the music a physical center at key moments, helping me find my way into what was otherwise a knotty, complex, and richly layered performance. The twin guitars created a swirling, psychedelic blues haze, while the horns punctured the air with urgent cries—short, cutting phrases. Though unfamiliar to me beforehand, Anna Abondolo proved to be a crucial stabilizing force, her bass lines giving the ensemble a sense of gravity beneath the swirl.

"Spanish Key" had a propulsive, driving groove, with the horns tossing out repeated melodic fragments in staggered, overlapping phrases that sketched the melody rather than stating it outright. The highly distorted guitars pushed the music toward turbulence, while the synthesizers added an eerie, string-like wash. The drum pattern kept hinting at endings that never quite arrived, giving the whole section a mysterious, slightly unsettled feel. A short version of "Miles Runs the Voodoo Down" had a more straight-ahead feel, with less density and layering, and was at times propelled by a rock-inflected groove.

The closing "Sanctuary" was the most stripped-down moment of the set, with the horns stating the melody in simple, repeated phrases. Electronics and percussion pulled back, leaving space and air around the theme as the ensemble gradually thinned rather than stopping outright. The effect was elegiac and restrained, with the music fading gently and releasing the tension that had built over the course of the performance.

At the end of the set, Bogie acknowledged Bob Weir, who had passed away just three days earlier, citing him as an inspiration. The reference resonated, given the influence of Bitches Brew on the Grateful Dead's music, an influence underscored by Miles Davis' opening for the band at the "Fillmore West" shortly after the album's release. It served as an apt ending to a unique and rewarding experience. The performance departed significantly from the recording, but by leaving the map behind and entering the territory, it did justice to an iconic album through reimagination rather than reproduction.

Tags

In Pictures

Bitches Brew Band

Dave Kaufman

Fully Altered Media

United States

New York

New York City

winter jazzfest

Max Roach

Members, Don't Git Weary

Le Poisson Rouge

Miles Davis

Bitches Brew

Lenny White

Adam O’Farrill

Jackie McLean

Jack DeJohnette

Tony Williams

Don Alias

Juma Santos

Jimi Hendrix

James Brown

Sly Stone

In A Silent Way

Nels Cline

Grey McMurray

Yuka Honda

Stuart Bogie

İlhan Erşahin

Alfredo Colón

Anna Abondolo

Tcheser Holmes

Billy Martin

Kenny Wollesen

Shahzad Ismaily

Dave Harrington

Ashley Kahn

Bob Weir

Grateful Dead

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.