Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Ron Carter: Always at the Center of the Action

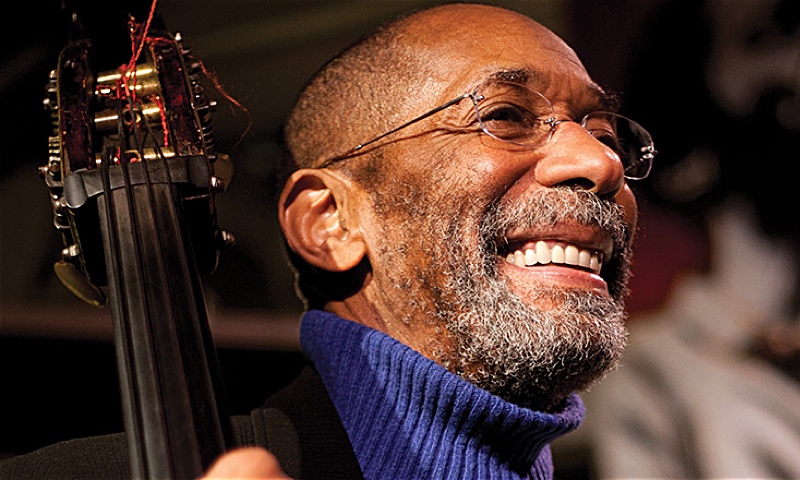

Ron Carter: Always at the Center of the Action

Ron Carter is such a bassist. More important than his reputation as a jazz legend and an NEA Jazz Master who has appeared on more recordings than any other bassist, are his enormous creative contributions and his participation in many jazz groups that have changed the music. His stint with the second Miles Davis Quintet, considered by some to have been the greatest of all time, is but one of the many times over six decades that he has been present "at the creation." More than that, Carter early recognized the key role of the bassist in the ensemble. For him, the bassist has always been the one who coordinates and brings out the best in all the musicians on the gig. As he has said, the bass player is the group's quarterback.

Dan Quellette's biography, Ron Carter: Finding the Right Notes (Retrac Productions, 2013) covers the gamut of Carter's life and career from his Detroit origins through his 2007 Carnegie Hall JVC Jazz Festival debut as a leader. In between, if you name a jazz ensemble or musician, the chances are pretty good that Carter has worked with them. You've probably heard Carter on recordings countless times without necessarily knowing it. But who is he? This interview is a down to earth glimpse of Carter candidly holding forth on a few aspects of his legendary life.

All About Jazz: Let's start with the desert island question. Which recordings would you take with you?

Ron Carter: Glenn Gould playing the Bach Goldberg Piano Variations. Bach's Brandenberg Concertos 1 through 6. Miles Davis' Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959). My own recording called All Alone (EmArcy, 1988). Any record by Johnny "Guitar" Watson.

AAJ: Reflecting back over the many years of your illustrious career, what, for you personally have been the major highlights?

RC: For me it's a highlight anytime someone calls me to make a recording with them, when any artist not only in New York but in the world, calls me to make a recording. To bring the music to the highest level: that's always my greatest moment. Any really good record date gives me another chance to make the music work. That's what I do.

AAJ: You're famous for the phrase "finding the right notes." It's the subtitle of your biography. It also sounds like finding the right musicians is what you crave in life.

RC: Actually, I often have to trust that when musicians call me, that I'm the right person for this specific project. They are often the ones who find me!

AAJ: Of all the groups you've worked with, which have you found the most challenging?

RC: That's not a hole I'm going to step in, because if I say that one group is special, it means the others were less special, and I don't want to give that impression. I approach every gig, every musician and group, the same way. I try to find how best to make it work. Each gig offers me a kind of laboratory experience. My goal is always to help the music reach the highest level possible, whomever it's with. So there's no particular group that I allow the euphoria to take over beyond the other groups.

AAJ: Sounds like you don't judge groups the way the critics do. You take each moment and situation and do your very best.

RC: What's important to me is that for each event I'm involved in, I want to make this concert or recording musically successful. My name will be listed on that album or concert. And not only can I fill their expectations, but can I fulfill what I'm expecting. Can I help to make another level of musicality or professionalism for all of us? That's my goal.

Origins and Early Career

AAJ: Let's go back to your beginnings. What first got you interested in music?

RC: When I was 11 or 12, the music teacher in grade school came and said, "We're going to start an orchestra here. So pick out an instrument you want to play to make this orchestra happen." Of all the instruments she demonstrated, the one that had the sound I loved was the cello.

AAJ: Your bio tells us that you wanted to be a classical musician, but racial discrimination made it virtually impossible for black instrumentalists to have a career in classical music. So, while at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY, you studied classical music, but, finding out that you would be most likely be locked out of a symphony orchestra, etc, on account of your race, you made a transition to jazz. Obviously, you've had an exceptional career as a jazz artist. Looking back, what are your feelings today about what happened then?

RC: My feelings haven't changed in that regard. I feel it was unfair, unnecessary. I feel like I earned the right to play in any environment that was available, and to be told that I could not is as hurtful now as it was then. How could you not resent that? People have said I hold a grudge. No, I don't hold a grudge. But I do have strong feelings about it even now. Why should I have been deprived of a chance to play on account of the color of my skin? I don't understand that. I'm getting to be 80 years old, and still nobody's ever explained to me, "Why?" They tell me they've made a lot of progress, but I don't see enough change that I can feel OK about it.

AAJ: I think you're right. There are still very few African American musicians in classical symphony orchestras. Have you ever been given an opportunity to play in classical ensembles?

RC: Yes, I have. Four years ago, I did a concert in Wroclaw, Poland. I requested to do Schubert's Trout Quintet. I wanted to play the double bass part, and they said "OK," and they were stunned how well I could play it. I said, "Why are you stunned? I grew up playing this stuff, man." As I'm talking to you now, I'm loving that experience. It was great!

AAJ: You grew up partly in Detroit. I understand you moved there around age 14.

RC: Yes. When my father was hired there as a bus driver, we moved to Detroit.

AAJ: At that time, in the 1950s, Detroit was an exciting city for both jazz and soul music.

RC: I wasn't yet a jazz player when the scene was that hot in Detroit. My jazz interests didn't really start until I went to the Eastman School of Music in Rochester when I was 18. So I didn't interact with the jazz scene in Detroit at the time. But I did go to high school at Cass Tech, which turned out some wonderful jazz players. Ira Jackson was an alto player there, and pianist Kirk Lightsey was my classmate, so I was aware they were playing the music, but I wasn't involved as a performer. I didn't hear a lot of the jazz musicians because I was studying classical music exclusively at the time.

AAJ: So, was your interest in jazz established when you studied at Eastman?

RC: I was studying to be a classical bassist, but when I was a senior, I was working weekends in the house band at a place called the Ridge Crest Inn. We fronted for a number of bands that came in on the train lines that intersected in Rochester on the way to New York City. So I was on the same bandstand as Dizzy Gillespie's band, Horace Silver's band, Carmen McRae and her trio, as well as Sonny Stitt. So I had a chance not only to hear them play but to talk with them, and then when they came in town without a band, like Sonny Stitt did, we played with him for a week. I hung withChuck Mangione, Pee Wee Ellis, Roy McCurdy, and others who were young jazz players at the time I was a student at Eastman. And those guys suggested that I move to New York. That's how I got to be a jazz player.

AAJ: Your early gigs in New York intrigue me. Many fans might typify you as mainstream, but before you joined Miles Davis, you did work with some musicians, for example Eric Dolphy and Thelonious Monk, who were considered outside the mainstream at the time.

RC: I made a couple of recordings with Eric Dolphy, but I was not part of his live performance groups. He often used Richard Davis as his bassist. Thelonious Monk used Sam Jones as his bassist at the time, and one night when Monk was playing at a place called The Circle in the Square in Greenwich Village, Sam got very sick and asked me if I could sub for him. So I gladly agreed, and then the week after that Monk hired me to work with him at a place in Philadelphia called Peps. He had a six night gig there, and I had to commute back and forth from New York because I was in school at the time. I worked at Peps with Monk, Specs Wright, and Charlie Rouse. That was a great time in my life.

AAJ: How did you relate to the avant-garde scene at the time?

RC: I worked with Don Ellis, Jackie Byard, and Steve Harris Zaum, who was really into a group called the 360 Degree Musical Experience, which included the groundbreaking pianist, Dave Burrell and Beaver Harris, a wonderful drummer in that style of music. I also played with drummerAndrew Cyrille. I played in that scene, so I knew all those guys. I loved the experience of hearing those guys make music in their own style and their own fashion.

AAJ: So you really liked the experimentation.

RC: Of course! You have to find the notes wherever you find them. There's no one set way to play.

The Miles Davis Quintet and Beyond

AAJ: OK. So then, somewhere along the line you were working with Art Farmer at the Half Note in Greenwich Village, and Miles Davis, as he states in his autobiography, came there specifically to steal you away from Farmer for his quintet that was changing personnel, but you respectfully asked Davis to get permission from Farmer to leave his group, to which Farmer graciously agreed, saying "It's your time."

RC: I was with Farmer's group with Jim Hall on guitar and Walter Perkins on drums. So when Art approved it, I went to California with Miles for the next six weeks.

AAJ: So from that trip to the coast, there soon evolved the famous second Miles Davis Quintet, with George Coleman and then Wayne Shorter on saxophone, Herbie Hancock on piano, you on bass, and Tony Williams on drums. Many critics agree that it was one of the most exciting groups in the history of jazz. Miles was an unexcelled musician, but a controversial personality. Did you by any chance see the recent movie, Miles Ahead?

RC: No, I have not. But someone sent me a DVD of it yesterday, so I'll look at it probably this weekend.

AAJ: The story line is largely fictionalized, but I would be interested to see if you feel if Don Cheadle captured Miles' personality accurately. For now, do you have any observations about how Miles was able to almost magically get a group to such an exceptional level?

RC: Really, that's something that only Miles himself could tell us. All I could tell you is that he had a definite view of how he wanted the music to be played, and he picked the musicians he thought would make it possible. I never really talked to him about that. I was just glad to be playing with him.

AAJ: You and Miles became friends. What did you talk about?

RC: We talked all the time about politics, the stock market, sports, and such. But our conversations did not include music.

AAJ: When I think about your extraordinary career, I have a particular memory of hearing you at Newport in 2004 with pianist Mulgrew Miller and guitarist Russell Malone. You did the most beautiful version of "My Funny Valentine" that I've ever heard. The improvisations were heart rending. It'll always stay in my mind.

RC: I miss Mulgrew so much. I listen to his records often, because I miss him so much.

AAJ: Mulgrew played with great clarity, yet he infused the music with feelings. He also seemed to be a wonderful person.

RC: I had a great time playing with him, and, once again, he was a good example of how I learned to play music that worked well, by interacting with great musicians like him.

For the Serious Bass Player

AAJ: I asked a friend, Lee Smith who is an outstanding bassist in Philadelphia, to suggest some questions I might ask you specifically about the instrument. By the way, Lee also happens to be Christian McBride's father. The first question he suggested I ask you is: How often you practice, and what you practice?

RC: As we speak, or during my career?

AAJ: Both.

RC: Those are different questions because when I was younger, I had lots of time, and I was looking to translate what I heard in my head to the bass. These days, my practice time is a little bit different. Right now, I'm busy all the time, and when I travel I don't take my bass, because the airlines charge so much for the excess weight, and they also sometimes lose and damage things. So I first see the bass I'm going to use when I get to the concert hall. When I go to Europe, I call it the bass du jour, the bass of the day. They give me a bass while I'm at the gig, so I can't just practice whenever I want to when I'm traveling.

Having said that, when I'm in New York, like I am for the next few weeks, I practice just two hours a day, and I practice just scales and etudes, including the Bille method and study books, the Storch-Hrabe etudes, and the occasional Bach cello suite transcribed for string bass. They help me with my skill level and my ongoing search to "find the right notes."

AAJ: When you were younger, did you practice improvising?

RC: No. All my practicing has been devoted to finding the notes, to developing my skill level on the bass. You're looking for a one word answer. It's a whole process. I never practiced jazz in my home, I never practiced walking time. I am concerned only about getting better and better at: "What are the notes that I hear, and where are they on the bass?" My practice of jazz as such is on the bandstand. When I'm playing with the guys in the group, I'm concerned about, "How can I find the notes that I hear, right now, not tomorrow!" Because the way they're playing it demands that this note be part of the chords they're playing.

AAJ: If I understand you correctly, your "at home" practicing is to master the fingering and the instrument. The improvising occurs when you're rehearsing and performing with the group.

RC: More or less, yes.

AAJ: Lee Smith also suggested I ask you how you maintain your fingering, agility, and strength.

RC: What I emphasize with my students is coordination, getting your left and right hand together to do what you want them to do. Coordination is all about getting your hands to find the right locations for the notes you want to play. The right notes at the right time and in tune. A lot of guys think strength is important, but I find that coordination is more the key to bass playing than the strength and power of the hand.

AAJ: I believe the bass came of age in the baroque period when it was used for the "continuo" part, the low register notes that establish tempo and chord progression. Its purpose was to support the music from underneath. Jazz bass continued that tradition with the rhythmic aspect such as the "walking bass." But ultimately jazz brought the bass to the center of the ensemble, just like the piano, the horns, etc., contributing soloistically, melodically, and contrapuntally. In fact, you yourself have played a major role in that evolution. Where, in your view, were the turning points in the early evolution of jazz where bass playing moved from being a backup instrument to being a featured one?

RC: One of the factors was that the strings were improved, more brands of strings with different sounds. Then engineers found new ways to record the bass, with bass pickups, amplifiers, cabinets, and speakers. It was as much an improvement in the physical aspect as it was the playing of the bass itself.

AAJ: Was that around the same time as LP records came out?

RC: Yes, roughly around that time. The engineers learned how to press the record so as not to lose the bass in the grooves of the record. Those kinds of technical improvements greatly enhanced the status and possibilities of the upright bass.

AAJ: Which bassists began to be featured as soloists earliest?

RC: I would say Jimmy Blanton with the Duke Ellington band, especially when they played duos. Blanton stepped it up to be on a par with the saxophone rather than an equivalent of the tuba.

Finding the Right Personal Notes

AAJ: What do you do when you have down time away from the music?

RC: The first thing I try to do is to stop all the music in my head. My first step is, can I stop hearing last night's gig in my head? Or last year's gig. I've got to do that long enough to change the light bulb in my living room! Or make a picture frame. Or go out and take a drive in my car. Just anything to get the music out of my head and be free of that responsibility for a while.

AAJ: So you like to just space out.

RC: I'm not just spacing out. I'm doing something that takes me away from the music. For example, I really enjoy a great meal. I have a number of things that I like to do that take me away from, say, the bridge of a tune. Also, I have four grandsons, and they are my hobby right now.

AAJ: Do you have a guiding philosophy of life?

RC: Someone once asked me, "When you pass away, what do you want your tombstone to say?" I told him I would like it to say something like, "Ron Carter was a wonderful bassist and a good friend." That's my philosophy.

AAJ: I think you've more than fulfilled those goals in so many ways. Ultimately life is very simple: basically it comes down to love.

RC: That's a good word to use. I'll buy that!

AAJ: I experience you as a forthright and happy guy. I feel that you exude joy when you play. I wouldn't feel that you have a bone to pick with anyone. But Dan Quellette's biography gives several examples of times when people felt put off by you. In view of my perception of you, those incidents didn't make any sense to me. But you have encountered times when you locked horns with people. Could you explain that discrepancy between how I perceive you and the tensions that have sometimes arisen in your life?

RC: I think it comes from the fact that I relate the same to everyone. So sometimes they expect me to relate to them because they occupy a certain status or position, and they think I'm an asshole because I don't do that. And people have all kinds of false expectations as to what you're supposed to look like or act like as a jazz player. But I'm just me, and if I don't meet their requirements or expectations, that's their problem. So sometimes I do rub some people the wrong way, but I have to be who I am regardless.

AAJ: It sounds like you might sometimes be blunt or frank with people. Some folks can't handle it.

RC: I'm aware of the political and economic implications of how I come across, and it's not my intent to turn people off. But I do have my own values and personality, and if someone bad-mouths me or asks me a question I can't answer, I can't be bothered with folks like that. I won't pretend to be someone I'm not under any circumstances.

A Word for Young Musicians

AAJ: You're an honest and forthright person, and I do think people have trouble with honest human beings. One final question: There's an exciting crop of young musicians who are coming up today in jazz through the conservatories and universities, but a lot of them are uncertain about what to do next with their careers. What would you like to tell them about that?

RC: A couple of things. First, if you aren't taking lessons, get a teacher. You need to have a sense of your instrument. What are the parameters of your instrument? Secondly, you have to free lance as much as possible so you can interact with others' points of view. Some guys just stick with one band. They don't get an opportunity to work with different players. Like, how does this guy tune his saxophone or guitar, certain things that affect the flavor of the music. And also, you should know the history of your instrument. No one is totally on their own. Everyone is influenced by some things that came before them. I think it's important to know something about jazz specifically, but more importantly about those who have played your instrument. Who played your instrument in the 1930s, what kind of horn did they use, what kind of reed did they use? So that it becomes less looking at yourself in the mirror and more like looking in a book instead.

Comments

Tags

Ron Carter

Interview

Victor L. Schermer

Jimmy Blanton

Scott LaFaro

Charlie Haden

Jimmy Garrison

Miles Davis

Johnny "Guitar" Watson

Kirk Lightsey

Dizzy Gillespie

Horace Silver

Carmen McRae

Sonny Stitt

Chuck Mangione

Pee Wee Ellis

Roy McCurdy

Eric Dolphy

Thelonious Monk

Richard Davis

Sam Jones

Specs Wright

Charlie Rouse

Don Ellis

Steve Harris

dave burrell

Beaver Harris

Andrew Cyrille

Art Farmer

Jim Hall

Walter Perkins

George Coleman

Wayne Shorter

Herbie Hancock

Tony Williams

Mulgrew Miller

Russell Malone

Lee Smith

Christian McBride

duke ellington

Concerts

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.