Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Jamie Baum: These Are Her Times

Jamie Baum: These Are Her Times

Courtesy Vincent Soyez

When you start writing music and choosing a theme or a concept, you never know by the time it comes out whether it will be relevant.

—Jamie Baum

In Baum's music, the present knocks against the past, development knocks against nature, repression against indulgence, reality against dream, destruction against creation, Qawwali music against jazz, even masculine against feminine to create a fusion that is all of the above and none. The compositions stretch across time like a chalk line on a tennis court, rich and satisfying as chocolate cake with lemon frosting yet deeply textured and totally listenable. You will hear patches of funk, solid swing, delicate weaves, Latin and African percussion along with the echoes of other mentors like Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

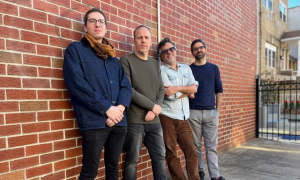

Any album on repeat is worth more than the sum of its parts. Why her Septet+ comes across as having tight playing, pure tones and slick chops is a tribute to its leader, who has put in the time and work to pull it all together from composition to practice. On—What Times Are These (Sunnyside, 2024)—she adds poetry, and vocalists Theo Bleckmann, Sarah Serpa and others. It is a step into the future. The human spirit requires surprise, variety and risk in order to enlarge itself. Imagination feeds on novelty. The result is music that infiltrates your cerebrum while a sweet mango melts on your palate.

Early on, Baum was drawn to India and through a 2004 Jazz Ambassador program from the Kennedy Center she was able to travel there, also going to Palestine, Thailand, Maldives, Sri Lanka and the country of her heritage, Israel. "I did grow up in the Jewish religious tradition," she affirmed. "I went to Hebrew school and studied Jewish music and prayer when I was very young, so I do have that in my ear, which is very similar to Maqam as is some of the approach of the scales and embellishment of the notes in Indian music, like that of the music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan."

Baum extended her study of Qawwali, exploring its ancient intersection with Jewish devotional music with the aid of a 2014 Guggenheim Fellowship, one of three jazz composers selected from nearly three thousand applicants to receive it. "I got turned onto Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and arranged some of his music for In This Life (Sunnyside 2013). There's just something about Nusrat's voice, something unearthly. It reminds me of Coltrane or Pavarotti."

What Times Are These showcases Baum's ability to be endlessly fun and innovative all at once while nudging large combo jazz to a whole new place. It gets you in its clutches and refuses to let go. The following conversation with her had essentially the same effect.

All About Jazz: Hi, Jamie. I understand you are playing a gig tonight.

Jamie Baum: Yes. Right now, I'm in a little cabin in Bloomington, Indiana.

AAJ: I read that you are originally from Bridgeport, Connecticut, which is in the state where I got started in life.

JB: My father had his practice in Bridgeport for a long time and then moved it to Fairfield, so that's really where I grew up. I was there until I left after high school, then on to college and then New York City. I live in this wonderful building complex called Manhattan Plaza. It is subsidized housing for artists and it makes it affordable to live in Manhattan. I like it because I'd lived in other places in Manhattan or Brooklyn, and this really feels like community. I know my neighbors and a lot of musicians that live in the building, so you're always bumping into somebody.

AAJ: Was your first recording Undercurrents (Konnex, 1992) with Randy Brecker, Vic Juris and others?

JB: Believe it or not, I never put out my very first recording. It was with an incredible group: Fred Hersch, Billy Hart and Mark Johnson and recorded at Fred's studio. I came up in a time where recording was a really special thing. I mean, not that it isn't anymore, but at that time, you had to have a record label, and I felt like I wasn't ready. I kind of regret not putting it out. Undercurrents was really the first recording that came out on a label.

AAJ: Will you ever release that first one?

JB: I thought about releasing it, but then I'd have to talk to everybody to get permission. Maybe I will at some point. I am not one of those people that looks back. I tend to look forward. That was then and this is now. Maybe, you never know.

AAJ: I read that you spent some time in India around the turn of the century. Was that when the first septet recording was out?

JB: The first septet recording was in 2004, Moving Forward, Standing Still (Omnitone). Before that, I did two State Department tours. They had a Jazz Ambassador program that was administered through the Kennedy Center and Billy Taylor. You had to audition as a trio. I applied with two other women, Sheryl Bailey and Jennifer Vincent, and really wanted to go to India. At that time, the program was to India and Pakistan, but they didn't feel it was a good idea to send three women to Pakistan. So, they sent us to South America and it was an amazing experience. Then I reapplied, but with a different group to go in 2001. This time we could go to India, also to Israel, Palestine, Thailand, Maldives and Sri Lanka. We were scheduled to leave in September. We were supposed to go to the Kennedy Center on September 10th to do a performance and be debriefed and leave on the 11th. I was in Bermuda and ready to fly there on the 10th, but needless to say was stuck there because of 9/11 and the Pentagon. They reinstated the tour the following spring, cutting out Israel and Palestine. But we did go to India and the rest.

The reason I'm mentioning all this is one of the beauties about the State Department tours was that they would set up these collaborative concerts in addition to your own concerts. So, I got to meet and play with a lot of Indian musicians who would turn me on to people I should be listening to or check out. I got turned onto Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, who I just completely became obsessed with. And I arranged some of his music for In This Life and in Bridges where I was commissioned to write a suite as a tribute to Nepal after the earthquake there.

AAJ: How would you describe the differences between Khan's music and others from that part of the world to what we are used to hearing in the West?

JB: The most obvious thing is that South Asian music developed in a different way than Western music. There are very high and intricate scales using quarter tones—though they don't call them quarter tones. It's in the embellishing and development of their scales and the way they present it in these very long pieces. They also highly develop the rhythmic concept, having what they call taals, these long rhythmic compound ideas. They all know how to count and somehow they all come out together, but they didn't really develop harmonically. For us westerners, it's like a kid in a candy store. You have all this melody and rhythm, but no harmony. I have a little disclaimer in the liner notes of In This Life because I wanted to say that the way that Indian music was taught for hundreds of years is that there were these sects that were musical families, and they would hand it down just like you think of Zakir Hussain. His father was a very famous tabla player, and he taught his son. They study for years and years before they ever perform in general. That's a very complex music, and I wasn't trying to write in that style or play that music because I have a lot of respect for how much depth there is and knowledge to play that music. It was more that I wanted to take certain things from that music and actually bring it into the jazz format, then see what I could do with that to expand in my own band and in my own playing to highlight or create new formats.

AAJ: Which one of your pieces would be a good example?

JB: There is "The Game," which was a piece of Nusrat's that had no harmony, and I wanted to expand that, find a way to express the intensity. Rather than it being in all 4/4, the way it was in his piece, I made three bars of 4/4 and a bar of 3/4. That gives it much more forward motion and some intensity. The way that he sings it is very fluid. So, instead of having the melody be very strict over the baseline, I have it coming in different places and going over the bar line, so it feels very fluid rather than strict. Another piece from In This Life is the title track where the opening is vocal improvisation of Nusrat that I transcribed. His was very, very fast and I slowed down quite a bit, but it really is a very good example of the way that he improvised and developed each note and would displace some of the rhythms. And he repeated it, but it would be slightly different, and that would give it an interesting build up. I transcribed that and put it in a piece for the Septet. The other really interesting aspect of the Qawwali music is that you would have the leader sing the melody and there was quite a bit of call and response. The group would respond and then he would improvise. So, I did this in my version of "The Game" as well. But everybody sings part of the transcription, and then there's a solo, and then they all come in and there's more of the transcription and perhaps more development. And then there's another solo. The last time that it's presented, it's enforced. You don't quite get a sense of harmony, but a little bit of harmony. But in that music, there's an intensity and buildup that is kind of religious. They're really trying to go into a frenzy and get into this state.

AAJ: He brought that concept over here with Michael Jackson and others. Khan's music became more westernized in a way.

JB: I'm certainly not the first to do that; it's just my interpretation and fascination with that music. Just this October, it was my fourth time playing in Katmandu at the jazz festival there and then Delhi to perform. I really love that part of the world, although this more recent recording of mine was in a different direction. I tend to get fixated on something for a while and then move on.

AAJ: Let's talk about your latest record. There was quite a gap between the previous one and What Times Are These.

JB: I have a large group, and it usually takes time to raise the money and bring them all together. That's really the main reason: raising the money then paying the bills off before I can start thinking about the next one. The second reason was covid. I actually had a studio booked for a smaller group that I had started called Short Stories, and we were supposed to play at the Rochester Jazz Festival and the DC Jazz Festival at the end of June, 2020, and then go into the studio. But of course, all that got canceled. We had been playing a bunch of gigs together. It was with Andy Milne, Joe Martin, Jeff Hirshfield and Gregoire Maret, and then Andy got a teaching job in Ann Arbor and Gregoire started going in another direction. But I've since started a quartet and hope to record in the fall. The last night with this other band was at the Keystone Corner, and it was the last night they were open. I went back to New York and was just watching everything get canceled, all my tours and gigs and teaching and just everything. So, I was home and in my one-bedroom apartment with my husband in Hell's Kitchen, Thankfully, I'm a composer, so I could turn to that. And too much Internet.

AAJ: You have said there is an exploration of poetry and culture in the human condition. Could you expand upon what you mean?

JB: I stumbled across this wonderful website that Bill Moyers had posted called "The Poet of the Day." Not having really been a poetry person, I liked what he did. He posted a poem, posted a video of the poet reading the poem, and oftentimes he had a video of him interviewing the poet about the poem. I really got into watching the poet read their poem, and it started to make more sense to me. I started to think maybe it's time for another Septet project and what have I not done? I'd never written with lyrics, with poetry and with vocalists. On the previous recording Amir ElSaffar sang wordless, but that was after the fact of writing it. Earlier, I'd written sort of a rap thing that Kyoko Kitamura read, but really never with the concept of writing lyrics.

I was drawn to some of these poems by Adrienne Rich and then organically turned to these poems all by women that were political, social commentary. Of course, when you start writing music and choosing a theme or a concept, you never know by the time it comes out whether it will be relevant. Adrienne Rich's poem—"What Kind of Times Are These?"—Is based on a poem by Bertol Brecht where it says, "what kind of times are these when it's too dangerous to even talk about trees?" He wrote that around the time of the Nazi invasion.

AAJ: "In the Light of Day" is the song with the singing bowls. Could you tell us something about that?

JB: I was thinking of it more as a prequel to "The Shiva Suite" that I wrote honoring Nepal. As my overall concept started to become clearer, it seemed like a really good opener because there was an arc to the whole recording of trying to tell a story. Maybe you saw this in India when you went where we went. It's just crazy. There are no traffic lights. They have one-way streets, but everybody ignores them, and people are on rickshaws and motorcycles. I mean, it's insane. And then there are millions of wires hanging everywhere. You almost feel like, oh my God, I'm going to get electrocuted here. But that's because of the infrastructure. If something doesn't work and they can't figure out which one it is, they just put another one up.

Anyway, living in Manhattan, New York City, the craziness of life, we're all just going about what we're doing, and then all of a sudden, we're stopped in our tracks almost like a plague. I wanted to give that feeling of crazy intensity. The other pieces are sort of reflection and dealing with certain things, because when you're stopped dead in your tracks, you have a lot of time to think. The next piece is from "To Be of Use" by Marge Pearcy. I felt like it talks about the importance of the normal worker, the everyday person, and how we become so enamored and beholden to money and fame. The people that push money around are more important than the everyday worker.

AAJ: The worker is forgotten, becomes invisible?

JB: The words are about the importance of the vase that carries the milk to the workers. That was one of the first pieces I wrote, and I had always written instrumentally. And of course, naively, I always come up with these ideas before I really think about what they entail. I thought, oh, I'll just write some lyrics for vocalists, and I had Theo Bleckmann in mind. I sent it to him and he's like, oh, no. So, I showed it to one of my old comp teachers, and the response was you don't know anything about writing for voice. They can't sing this. I ended up just writing it for instrumental but reading the poem in the beginning. At that point, I started to do a little more studying and learning about the voice and syllables and chest voice and head voice and how to think more about writing for vocalists and expressing things with lyrics.

AAJ: The next one, "An Old Story," is a really cool piece from a poem by Tracy Smith that features Aubrey Johnson and Keita Ogawa.

JB: That one talks about how things got really bad, and then all the animals were hiding. It was in two parts where in the second part you change meters and it becomes much more uplifting. It's brighter. We realize what we lost and the animals crept down from the trees. After reflecting on that, things would be better, hopefully.

AAJ: We always have hope.

AAJ: "In Those Years" is also by Adrienne Rich and talks about how we lost track of the meaning of "we"; that we're very focused on "I." So, I wanted to highlight that. It has this very annoying ostinato in the beginning where usually you try not to do that for too long. I did it for too long. I wanted it to be annoying. Then further where there's just the trio with the bass, piano and Theo, where it speeds up and he's saying "I,I,I,I ..." almost in a frenzy to give it more intensity. Theo did some amazing overdubbing on that, some looping, which I think gives it a really cool vibe.

AAJ: "I" can be seen as virtue signaling for identity politics. It's easier to control people if you put them into separate boxes instead of thinking of people as "we" like you said, collectively, which is a perfect transition to the title song, "What Kinds of Times Are These?"

JB: That one is about when it's too dangerous to even talk about trees. Kind of timely, I think. And I had Sarah Serpa sing on that. I wanted a very sort of pure sound, and she fit. And then "Sorrow Song." I was reading Lucille Clifton's poem; it just sounded like rap to me. Ethiopian eyes, American eyes, Vietnam eyes, this sort of brief rhythmic thing. I was always enamored by Kokayi. I'd heard him in Steve Coleman's group and Terri Lyne Carrington's group and Nate Wood. I was really wanting to come up with something that would fit, and he did an amazing job on that.

AAJ: Sarah Serpa was featured again on "My Grandmother in the Stars."

JB: That is probably is my favorite piece on the album. It has a lot of meaning for me because of a couple things. One, I was taking care of my mom for about three years. She had always been my biggest supporter, and she was developing dementia. I was court-appointed as one of the co-conservators, which means I took care of all her health needs. I would go out to see her every other week. She lived in Connecticut, and it was really hard to see the progression, but I wanted to be very positive when I was with her. Sometimes I would take the train, and this tune was always going through my mind called "Every Time We Say Goodbye." Do you know that song Betty Carter did? And Carmen McRae, a lot of people. Every time I say goodbye, I cry a little. I wanted to write something that would connect me with those feelings to my mom. And I read this poem by Naomi Shihab Nye, who I was subsequently in touch with and found out she wrote that for her grandmother in Palestine.

She's Palestinian, although she grew up in the States as her parents immigrated here. She knew that when she saw her grandmother, it would be the last time. It's really beautiful. It starts out as possible. We will not meet again on Earth to fill this; to think this fills my throat with dust, and then there's only the sky tying the universe together. The other thing is that I gave myself some exercises for things I wanted to try to do with this. I wanted to have the feel of a singer/songwriter that writes using lyrics, whether it's for Broadway or film. I got my Masters in composition, so I took some film score. With film, things need to be obvious. You need to write something that elicits a certain emotional response that's connected to the movie. For example, if you have a scary part, you're going to hear a diminished chord. But if the lyric is hopeful, the melody line should go up.

AAJ: I get it. If it's sad, it goes down. It starts out being possible, so it goes up. We will not meet again on Earth, and that's sad. So, it comes down.

JB: Yes, and then the next one is "I Am Wrestling with Despair" by Marge Pearcy. And of course, that is apropos about men making decisions about women's bodies and that kind of thing, so I wanted that to have a dark vibe, but not too dark. And then "Dreams" was something that I had written previously for a cousin of mine who had gotten pancreatic cancer but was just an amazing, inspiring person. He played jazz drums and was a psychologist. It felt like it fit because, okay, we've gone through all this stuff and now need something uplifting. And "In the Day of Light" to finish is a bookend to "In the Light of Day."

AAJ: That is quite a journey. What would you hope listeners take away from the album?

JB: Well, first and foremost, just hoping that they enjoy the music and it moves them in some way. I feel any art is really personal interpretation. You know what I mean? If you see a Jackson Pollock, different people are going to have a different response, or it'll conjure up something for them. I think that most artists usually do art for themselves. If it interests or excites me or keeps me engaged or moves me, then hopefully it will also other people. But this album, of course, is a different project than my other ones, because you have lyrics. It's no longer completely open for interpretation as something without lyrics. They're very specific things, but at the same time, modern poetry doesn't necessarily rhyme or isn't necessarily really clear about its meaning. A lot of the poems that were on the website, they don't necessarily rhyme or they don't necessarily fall into a symmetrical state or rhythmic structure. My choices were like, okay, is this something I can figure out a way to put music to it?

AAJ: I don't think there is any doubt you figured it all out. I am especially loving "Dreams," how it starts with French horn, then alto sax, play the ostinato and then everybody else comes in with the piano. How are you able to manage the eight pieces so smoothly?

JB: Well, it's actually nine with the vocalist. That's why we called it "Plus" because when I was doing the South Asian influence music, it felt like it needed a stringed instrument, a guitar, so I added Brad Shepik. So, it's at a minimum of nine, and then if you add the percussion and the other vocalists, it becomes more.

AAJ: Do you have a different approach when you're in a quartet as opposed to the septet or plus or nonet or however many instruments that group becomes?

JB: Like most jazz musicians, I started out playing and learning the jazz repertoire. A lot of standards, both jazz and Broadway show tunes that were turned into jazz standards like "Stella By Starlight." While I always like to write, I'm an improviser, too. In the quartet format, it is more geared toward that tradition, whether it's more modern tunes or my original tunes. I look at that as more a vehicle for improvising, and at least for me, more intimate interaction with myself and the rhythm section. Because with the larger group, my focus is more on the composition and orchestration and trying to connect the improvisation to the material. I'm trying to hear that it's not so much about me, it's more about what personality would highlight this composition or what I'm going for conceptually with the way they improvise, or what does this composition need at this point in terms of a solo to give contrast or highlight what I'm trying to say with the music. For me, this fulfills a different right brain, left brain thing.

AAJ: On your website, it says you played gigs in California this January (2025). Who was in your quartet?

JB: We did a tour of Northern California, SF Jazz, the Redwood Alliance and others. It was a lot of fun. I had Leo Genovese on piano, Matt Penman on bass and Rob Garcia drums. All of them were great.

AAJ: And today you are in Indiana playing with whom?

JB: I have been working with a pianist (Monika Herzig) who is originally from Germany, but lived in Bloomington for quite a while and was teaching at IU before getting a job teaching in Vienna. She's sort of going back and forth, but she started an all-women band over ten years ago. I did some gigs with her in New York a couple weeks ago, then here, New Orleans and back, and today's the last day. We have some clinics we're doing this afternoon, and then tomorrow I'm flying to Moscow, Idaho, where I'm going to be a guest at the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival there. I'll do a couple of clinics and the big band is going to play a couple of my charts, and then they wrote a chart for me. Then off to Germany with Monika Herzig. Last October we went to Nepal and India as part of her tour, and then we went to Germany, Austria, Spain and Egypt too.

AAJ: You have been described as being political about women in jazz. Has it opened up more now for women than it used to be in the last century? The first time I ever saw a woman leading a jazz combo was JoAnne Brackeen in San Francisco during a trip out there in the '80s.

JB: When I started, there really weren't too many. Carla Bley, Joanne, Marian McPartland, not many. And then more came along like Terri Lyne Carrington and Geri Allen, Jane Ira Bloom and Jane Monheit. There were more, but of course, you could name them on a hand or two.

AAJ: But it's gotten much better, hasn't it?

JB: I teach combo at Manhattan School of Music, and I work with the ensembles in addition to some private lessons. And in the last few years, I am beginning to see more and more instrumentalists, really good trumpet players, drummers and bass players. It's certainly more now, but it's not as reflected in the festival circuit or the recording studio. I mean, you see a few over and over again that are getting some play, like Anat Cohen and Terri Lyne, but hopefully that is changing.

AAJ: During a conversation with Vanessa Collier, the saxophonist, she told me about having to drive overnight to get to a festival in Chicago. She was tired and asked to switch her slot until later, but the promoter said, no, there is another woman playing then and we can't have two back-to-back.

JB: Actually, that happens a lot. They'll say, oh, we already have one woman. We already have a flautist or something. So, okay, how many pianists do you have? How many trumpet players do you have?

AAJ: You do a fair amount of teaching. What do you find satisfying about it?

JB: I have done it in a part-time fashion because I love to tour. Many places, if you're full-time or sometimes even part-time, they have strict stipulations about how much you can miss. But I teach at Manhattan School and the New School, although I get students that come to my apartment. I've been doing that since 2006, and some years there are none; some years there are many, but it's flexible. The thing I like the most about it is that they really kick my butt. It's like, oh my God, I better practice this because they want to work on things and I need to be a step ahead of them. So that has me going back to things that I used to work on. It never hurts to brush up on or learn new things and new approaches. I think I learn as much as they do.

AAJ: They must appreciate you offering them some of the things you have experienced through the years.

JB: That is nice to be able to offer them things I have learned. I work on the students' composing, and I'm able to point things out to them that they might not be aware of. Like I said, the level is very high, and so they're bringing things in and turning me onto things that I want to know about. A clinic that I've been teaching for several years is called a Fear Free approach to improvisation for the classically trained musician. That's working with musicians that don't have any experience with improvisation. I enjoy that too, because I think that you are opening up a whole 'nother world for people.

AAJ: Have any of your students gone on to make a record or play in a group that records?

AAJ: Oh, yes, a lot of them. Some of them I've even worked with, and they've brought me on tours, and that's always fun. Remy Le Boeuf is doing really well with his composition. And Steven Lugerner was a student I had, I think around 2007 for three years, who I taught composition. He went to the New School and now he's head of the Stanford Jazz Summer Institute program. And Elsa Nilsson is a flutist who has some records out and is doing a lot of touring.

AAJ: So, with all these things going on, how do you ever find time to practice?

JB: Well, I practice every day. Sometimes it's a little tricky on tour because there's just not time. You get up at five in the morning and fly somewhere, and then you just have time to eat and do a soundcheck. Yesterday I was here and had the day off. And even though I am at this beautiful farm Airbnb place, and I should have gone out for a walk, I was in all day finishing a chart that I needed to send off because my eight-piece band ... well, actually, we're thirteen, we're playing at the Kennedy Center as part of the festival and going on a little tour. So, I was sitting at the computer till about three. When I'm home, though, I put in a minimum of two to three hours.

AAJ: What in particular do you practice the most?

AAJ: The first thing usually is technique, because the flute is very similar to trumpet. If you know any trumpet players, they're always fretting about the embouchure and getting a certain sound. That really has to take precedence because in order to be able to express myself or play what I want to play, I have to be able to get that sound out. It's not like piano. And then it just depends on what is going on. A week before I was leaving here, I got contacted at the last minute to do somebody's record date a week later, and they sent me all this music. So, now I'm working on somebody else's music other than my own. Then I'm always trying to work on things I can't do, whether it's a tune or chord progression. There's always something.

AAJ: Do you ever just practice solo rather than with, say, backing tracks?

JB: There are so many aids nowadays at your fingertips, certainly unlike when I started. You have the metronome, play-alongs, drones or Real Book accompaniments. But I always feel for horn players that it's important to do both. Be able to play without any accompaniment and feel the time or work with a metronome, and then also play with the accompaniment. I see so many horn players or whatever doing solo recordings or solo projects, and I always sort of look at that in the distance. Okay, that's a final frontier. Someday I want to do that. But I love writing for a lot of instruments.

AAJ: Is there a person you've never played with that you would like to at some point?

JB: Dead or alive? Both? Well, when I was first starting out, one of my first jazz teachers was Jaki Byard and I was in an ensemble with George Russell. I always wanted to play with Miles Davis, but of course that didn't happen. Alive? Honestly, there's so many people that would be really exciting to play with, too many to name. It depends on what I'm listening to at the time.

AAJ: I read that you started playing piano when you were very young and eventually moved on to woodwinds, but I'm interested in how you became a jazz musician.

JB: When I was going to high school, I had quit piano or at least taking lessons. My parents had a place for the summer on the beach, and there would be guys sitting outside playing guitars or at school, the marching band. It just seemed like a fun thing. I was never serious about music. I'm a late bloomer, and I wasn't even thinking I would be a musician at that time, but it just seemed like a fun mobile vehicle to have a flute and be able to play with others.

AAJ: Were you part of the high school band?

JB: I played in the marching band, but I can assure you I was probably 14th flute playing home notes while chewing gum. I was not very serious, and I wasn't one of those kids that played in the regular band or orchestra, going to the competitions. It was very minimal, not serious. I took up a little saxophone, but honestly, in those days, my parents were not pushing me to play sax. It wasn't really a girls' instrument, and they were saying I really needed to just focus on one. And since I wasn't practicing much anyway, I kind of liked the flute because it was very versatile. You could play classical or you could play rock or jazz.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Jamie Baum Concerts

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.