Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » Not Like Before: Michael Robinson's Jazz Without Borders

Not Like Before: Michael Robinson's Jazz Without Borders

...jazz and Hindustani music are centered on expression, known as rasa in India. Shringara rasa, representing human love, divine love, eroticism, and the creative spark of life, is the chief emotional and spiritual impetus for both Hindustani music and jazz.

I've been fortunate to know masters of improvised music personally from jazz, Indian classical and rock. From jazz, I studied improvisation with Lee Konitz, later becoming close friends. From Indian classical, I first studied with Harihar Rao, the senior disciple of Ravi Shankar, who earlier taught Don Ellis, Lalo Schifrin, Ed Shaughnessy, George Harrison, Robby Krieger, John Densmore and Brian Jones. Subsequent Indian teachers included Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy, who founded the first ethnomusicology department in America, Pandit Jasraj, the leading Hindustani music vocalist of our time, known in India as the Sun of Music, and my current Guruji, legendary tabla player Anindo Chatterjee. From rock, I became good friends with Ray Manzarek, including working on some music projects together, and had a memorable encounter with George Harrison, who at one point in an extended conversation was moved to sing his favorite Raga Charukeshi for me.

Luckily, all of these masters of improvisation had a shared fascination with my ideas and questions. I was taken aback when Nazir invited me to lecture at his Indian classical music class at UCLA, introducing me with the statement, "He probably knows as much about improvisation as anyone." It was a beautiful coincidence when first meeting Nazir, to learn his favorite jazz artist was Lee Konitz whom he first heard in the fifties.

Having decided to make composition my music focus, my perspective was unique, including believing jazz became the true classical music of the Western world beginning in the forties, joined by various forms of rock and pop beginning in the sixties.

My jumping off point for composition was the Interstellar Space album of duets by tenor saxophonist John Coltrane and drummer Rashied Ali, following the model of John's music hero, Ravi Shankar, with sitar and tabla duets. Of course, Shankar also had a tamboura or tambouras playing drones. My sense was this album was the furthest jazz had gone, and thus Western classical music, too, and my vision was to follow with a new evolution of jazz performed by computer and sound module, eventually naming the software and hardware used the meruvina,* preferring a poetic name over technical ones.

I felt that human musicians were incapable of going beyond what John Coltrane had accomplished, and set about tapping into the unique expressive and technical virtues of the meruvina, believing this was the instrument capable of being in the zeitgeist, as the saxophone had done with jazz, and the electric guitar had done with rock.

Different from most anyone else, I absolutely choose pure meruvina-performed music without any human interference during performance. In other words, working from fully notated scores, I programmed the meruvina to perform my music in real time without any overdubbing. Again, most others preferred human interactivity with technology, but I personally found this a self-defeating return for nostalgia of the past; a compromise, compromising in music being antithetical to my being.

There had been notable premonitions of Indian classical music, but it was a vocal concert of Hindustani music heard at Washington Square Church in Greenwich Village that proved a rubicon, taking me through the door into another realm of music awareness, connecting with earlier glimpses of expression and form experienced with the music of Morton Feldman and Brian Eno.

A series of fortunate coincidences led me to the home of Harihar Rao in Pasadena, and I had entered the realm of the Maihar Gharana founded by Allaudin Khan, which includes Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Nikhil Banerjee and Hariprasad Chaurasia.

Rather than studying sitar or tabla or even vocal music with Harihar, I wished to study concepts of melody, rhythm, form and expression, later doing the same with Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy, Pandit Jasraj and Anindo Chatterjee among other teachers. And when I had opportunities to interview Zakir Hussain and Shivkumar Sharma, the latter twice, I treated the interviews as private music lessons, gathering pertinent information for synergistic effect with study of their recordings and live concerts.

After all, we are what we listen to. To my fanatical study of jazz recordings and live performances, I added the same with Indian classical music. Rock and pop on the other hand, I studied equally intensely through recordings finding live concerts much too loud.

My compositions and realizations for meruvina evolved to contain elements of improvisation in unprecedented form. This was how composition must be in my view given how the great music of my time, jazz and Indian classical music, is improvised, together with a good deal of my favorite rock. You see, when Indian classical music came to the Western world, it, too, became a dominant form of Western classical music even though the key performers were from India.

I gradually began using my interpretation of raga form for composing, with many works really symphonies in terms of their scale, oftentimes an hour or so long, with several three or more hours long. Composing and programming realizations for meruvina was very challenging and exciting.

Then, one day a friend's mother who was in her nineties, upon learning I was a composer, asked me to play the piano for her, having a gorgeous hundred-year old Steinway grand in her living room. So it began, three hours or so every Sunday I played the Great American Songbook for Jocelyn, including a break for coffee, fruit and pastries. Jocelyn had a mesmerizing dramatic presence filling any room she was in, like when the leading actor in a classic film unexpectedly makes their first appearance and we practically gasp in wonderment.

We soon found out we shared the same March 11 birthday. I learned from her daughter how she claimed to talk to God, and was fervently connected with Israel, coincidently being from the same town in Wisconsin as Golda Meir. Her most recent activity was creating sublime rings, cuffs and necklaces, having studied with a master Italian jeweler. These were only for herself and those close to her. Jocelyn was acutely musical, with intelligence off the charts. She was a gifted singer and pianist, including performing at her temple.

She sat close to me in her wheelchair when I played, always immaculately dressed with a different color ribbon in her hair each time. Every molecule of my playing she noticed, being drawn to my interpretations of simply the melody and the modern jazz chords found in the six Real Books I insisted on having for my performances. Even with a very limited technique because I played the piano about once or year or less, not having any keyboard at home, Jocelyn knew there was something going on musically. That something was my knowledge of how jazz greats interpreted these songs, some of which I had gleaned.

One day, arriving early, waiting at the Steinway for Jocelyn, I began to wonder about possibly improvising on these songs, how to go about doing it. I had been improvising on ragas and engaging in free improvisation at the piano on my own time, and felt the need to try something else.

I recalled watching a video in which Bill Evans talked about how he refused to give his jazz piano secrets to his brother because that would deprive him of self-discovery, finding a way to play on his own.

What occurred to me sitting there was my attraction to how Lee Konitz's teacher, Lennie Tristano, was fond of using his left hand like a walking bass. So I started doing this with the melody in the right hand, and then continued with improvisation in both hands at once creating two-part counterpoint, though the left hand was more in an accompanying role. At first the feeling was perilous, like jumping down a waterfall hundreds of feet to a rushing river, hoping to swim after the initial dive. I came alive.

While improvising I realized that my orientation, while definitely playing a personal form of jazz, was almost equally colored by raga consciousness and feeling. In fact, there was no differentiation between jazz and raga, which were coalescing equally without a second thought. And this led to raga-like durations for my improvisations.

What I was doing was really very simple, playing what I felt and heard, which is what Lee Konitz told me he does when playing at his best, not consciously thinking of chords, for example, only sounds.

More so, at one point Lee confessed he had no idea what people are talking about when they say they play what they hear, indicating how true improvisation is so instantaneous everything happens at once, there being no time to respond to anything inner or outer, rather your music happens fully in the moment. Of course, the way one hears and feels is intrinsic for allowing such an elevated state of play, a level of extemporization that comes with intensive practice and experience.

Just prior to leaving New York for Los Angeles, I had been a guest of Phil Schaap while he hosted the John Coltrane Birthday Broadcast at WKCR FM at Columbia University in Manhattan. At one point I asked Phil what he thought the future of jazz might be. This was September 23, 1990. Phil thought deeply for a few moments, and then said his best guess was it would involve developing innovations of Lennie Tristano. Now, around thirty years later, I was coincidently doing what Phil had prophesied, building on an innovation of Tristano.

As I continued improvising on jazz standards, I came to the realization they are truly the ragas of jazz, with important connections and divergences.

In December 1997, I attended a lecture Ravi Shankar gave at UCSD, and was stunned by how he clearly did not understand jazz, stating it to be an inferior form of improvisation compared to Indian classical music, which simply isn't true. That would be like saying Japanese cuisine is inferior to French cuisine. Obviously, to make comparisons in a meaningful way one needs to have a deep knowledge and understanding of both cuisines, and it was evident Ravi, like many others, simply had not had the time for such study beyond his brief collaborations with some jazz artists. Actually, Ravi has written widely contradictory statements about jazz, and how it relates to Indian classical music, so it's very possible what he said that night was a miscommunication.

Needless to say, if jazz and Hindustani music were identical there would be no reason to make any comparisons. The notion that they are too different to compare is uninformed. It would merely be ethnocentric to state that either form is superior to the other. Infinitely more useful and beneficial is to embrace their respective virtues together with our personal preferences.

For example, I've noticed how the only musician who can match the rhythmic fluidity of Charlie Parker is Alla Rakha and vice-versa, but it takes a degree of sophistication with both jazz and Indian classical music to make such comparisons.

I had the pleasure of meeting Ravi, and he even offered to teach me, which would have been wonderful, and I wish I had pursued the invitation more persistently. I know he would have enjoyed hearing the remarkable parallels between himself and Charlie Parker, both born the same year, and both utterly transforming their respective disciplines, Hindustani music and jazz.

One may easily write many books on the subject, it being vast and complex, but here are a few opening thoughts comparing jazz and raga.

Both jazz and Hindustani music are essentially theme and variation forms based upon improvisation. Indian classical music, which includes Hindustani music and Carnatic music, has evolved over hundreds of years, while jazz is roughly one hundred years old.

Together with their theme and variations modus operandi, jazz and Hindustani music are centered on expression, known as rasa in India. Shringara rasa, representing human love, divine love, eroticism, and the creative spark of life, is the chief emotional and spiritual impetus for both Hindustani music and jazz. Additional rasas, including Veera, Shanta, Hasya, Adbhuta, Karuna and Raudra also apply equally well to jazz.

Ragas provide the improvisational medium for Indian classical music, while standards and blues forms provided the template for jazz in my personal favorite periods of modern and swing, adding now for my personal vision of avant-garde. Ragas and standards are both composed forms of genius, capable of countless interpretive variations, only limited by the imaginations of the practitioners. It is believed that ragas always existed, and were just waiting to be discovered. One may feel strongly enough about standards to hold a similar belief.

One key difference between jazz and raga is how standards modulate with chord settings while ragas have one tonal center. So, how am I able to bring raga consciousness to jazz standards given that monumental gap? Well, it's easy. Like I said, I play what I feel and hear, and following the council of Lee Konitz, one of the major architects of modern jazz, I avoid thinking consciously of chords, rather of sounds.

What I'm feeling and hearing while improvising is closer to Bela Bartok's polymodality than Arnold Schoenberg's atonality, representing two different ways of bypassing conventional tonality and harmony. Bartok's polymodality dovetails beautifully with the concept of ragamala, meaning garland of ragas, not limited to any single raga. Of course, I'm taking ragamala further, eschewing any particular tonal center.

The lyrics of standards are more important than the equally essential music according to none less an authority than Frank Sinatra, who stated: "The written word is first, always will be. Not belittling the music, but it really is a backdrop. To convey the meaning of a song, you need to look at the lyric and understand."

This truth applies equally well to instrumentalists being familiar with the lyrics of songs they play, an essential component of how the finest swing and modern jazz artists made improvisational magic. Just because something isn't explicitly stated doesn't mean it isn't there. The lyrics existed in the consciousness of those musicians imparting shared meaning to listeners with like understanding, inexplicably intertwined with the musical thrust.

With both my meruvina music and piano improvisations, I relate strongly to santoor artist Shivkumar Sharma, with whom I had two memorable encounters in the form of interviews, in addition to attending live performances and closely studying his myriad recordings. The santoor is an ancient precursor of the piano, both being struck-sound melodic percussion instruments, unable to replicate the melismas of the human voice, bowed instruments, or even plucked string instruments and wind instruments both brass and woodwind. Thus, the practitioner must find forms of expressiveness unique to their particular instrument, treating those supposed limitations as sui generis virtues to be exploited. After all, the Gatra Vina, the human voice, Gatra meaning body, and Vina meaning musical instrument, is the only musical instrument created by God, with all others invented by humans.

Red Garland has become my favorite jazz pianist together with Lennie Tristano. My piano chord concepts come equally from both Garland and Henry Cowell, a contemporary and key supporter of Charles Ives. Cowell, Jocelyn and myself share the same March 11 birthday. Cowell inspired the Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano by John Cage, which many regard as his finest composition. Cage, similar to Ornette Coleman, was a historically crucial catalytic musical influence, helping free us from creative inhibitions, starting from an empty canvas, the way Steve Reich did, rescuing Western composition from serialism.

Musicologist and arts administrator Leonard Altman asked Reich to mentor me, who then assisted by imparting basics of being a composer, including inadvertently convincing me to move into New York City, which proved utterly transformative.

Not aesthetically content with music based on patterns, I began adding through-composed melody and percussion voices to melodic and percussion ostinatos.

I also had the pleasure of spending memorable time with John Cage at his Chelsea apartment where he examined my early scores. When I showed up at his door that bitterly cold winter day, John nervously eyed the large red suitcase I was holding, seemingly wondering to himself if my intent was to move in, but this was only to accommodate oversized scores.

Even though I rarely if ever listen to the music of Cage or Coleman since initial exposures (though one might argue we're all listening to the music of John Cage all the time), touched more by their concepts, their key importance in Western music cannot be overstated.

One friend cautioned me about using the term "jazz piano," expressing how that terminology might give the misimpression of what I'm doing being mainstream. I considered simply saying what I did being "piano improvisation," but then realized that would be depriving me of my rightful heritage, including being a direct disciple of Lee Konitz, so I've embraced the idea of being a jazz pianist with a personal approach to improvisation.

My initial jazz exposure was overwhelmingly to modern, modal and avant-garde. Swing had been a developed taste, only fully appreciating it in recent years, finally recognizing how it is second to none in every sense. In fact, I feel close to the harmonic sense of swing because it is less specific than modern, including being closer to the standards in their original composed form. So, in a sense, I am returning to original sources, the standards in their original form before they were adopted by modern jazz artists, and swing artists, too, if to a lesser degree.

I've assimilated the duration of ragas while finding a personal way of the playing of jazz on a conventional instrument, also claiming my hereditary stake whereby Benny Goodman was a key architect of jazz, Jewish American like myself, and the co-progenitor of so many artists including none less than Lester Young, who then became a key influence upon Charlie Parker.

And the ragas of jazz, the standards, are largely the heart, soul and mind of Jewish American composers and lyricists, while the unique musical tempest of jazz itself was born by African Americans, joined synergistically by Jewish Americans, Italian Americans, other European Americans, Latin Americans and artists from additional cultural heritages both here and abroad.

Given how Charlie Parker's mother was Native American, and his Dad was half African American and half Native American, the influence of Native American culture on jazz has yet to be explicated, Parker being one of many such examples.

It remains a remarkable coincidence how Bird's most exalted track, arguably the most exalted track in jazz history, is "Cherokee"—arranged as "Ko Ko"—about a young Native American woman, including Ray Noble's inspired love lyrics, especially the poignant bridge lyrics expressing the theme of separation so prevalent in the poetry sung in ragas, that no doubt inspired Bird at the time. Again, the music is only half the story of a song, like a skeleton without a body.

At one of our lessons, I asked Lee Konitz how he achieves continuity in his improvisations. Lee immediately and honestly replied, "I don't know." The Zen-like wisdom and profundity of his non-explanation is evident. Go by instinct and don't overthink it.

During my time with George Harrison, he said something similar to Lee. At one juncture we were discussing favorite guitarists (George said Jimi Hendrix was his absolute favorite, while I went for Johnny Winter, long believing his playing from the late sixties to early seventies being the pinnacle of rock guitar), and when I praised his own miraculous style—all of these are truly guitar gods—George modestly confessed how he had no idea what he does while playing, it being entirely instinctive and natural. Years later, he sang, "If you don't know where you're going, any road will take you there."

Improvisational philosophy learned from my Indian teachers regard elaboration, the way of doing things, as divine, sacred ritual offered to the presiding deity of the raga, oftentimes Shiva, Vishnu or Mata Kali, or the feeling of God or nature, whichever one's preference.

Central to what's known as "swing" in jazz is a distinctive style, unique musicians swinging their own original way, some so unconventionally it becomes an intrinsic part of a new approach to improvising jazz, allowing to articulate inner feel into sound.

One night while practicing, it occurred to me how the seven saptaks or octaves of the piano match the seven chakras of the human body. Checking online, I was unable to find anyone else noticing this correlation. Pondering how to explain the three extra swaras or tones at the low end of the keyboard, I settled poetically upon Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma, or the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.

Were any of the inventors and developers of the piano aware of corresponding to the seven chakras? We will never know for sure, but chakras are one of many fascinating, complex concepts from India remaining centrally relevant today like raga, chess and yoga, all of which are best learned privately like jazz.

It seems I utilize the extreme octaves of the piano more so than most others, finding each of the eighty-eight swaras essential for my purposes.

How you play the piano is just as important as what you play, the two being inseparably intertwined. This includes touch, tone quality, and one's relationship to the pedal.

And how does someone learn to improvise, drawing from either or both jazz and Indian classical music traditions? Again, the words of Frank Sinatra are most insightful, applying equally well to the disciplines of both singing and improvisation: "I think—to get serious for a moment—in any attempt, in any business in the world by any human being, to obtain longevity you must work hard. And seriously work. People told me if you want to sing you eat songs, you sleep songs, you drink songs, you dream songs. And you stay with that thought the best you can all the time. And suddenly it begins to grow; it really grows into you. I think an athlete has to do the same thing, or a cop—he walks a lot so that by the time he's finished he gets the job. But as clear as I can make it, you got to live with it constantly, twenty-four hours a day. I don't care what business you're in."

Echoing this thought, Anindo Chattejee told me music has to be 24/7.

My initial series of piano improvisations were purely solo piano, and I truly love how exposed that setting is, nowhere to hide, a true baptism of fire. Then, I began thinking of collaborating with a percussionist as John Coltrane did for Interstellar Space, and how this is the basic format of Indian classical music, namely one vocal or instrumental artist with a tabla player, my left hand having become a combination of double bass from jazz and tamboura from raga.

I thought to ask my Guruji, Anindo Chatterjee, if he wished to record together, and most fortuitously, together with the enthusiastic support of his disciple, Ehren Hanson, Anindo wrote: "We ll have an amazing rec. i guarranty. Dont feel nurvous. Just play openly and relax [sic]." We ended up with four albums recorded over two days, including extended raga-like lengths for "Cherokee" and "Hey Jude."

My vision for our collaboration was how jazz is largely about a triple feel superimposed on a single beat most often using duple meters, creating an inherent tension replete with creatively expressive accents and syncopations, and how we are dualistic in terms of ears, hands, arms, legs, and walking. With this in mind, and knowing of connecting thekas or tabla patterns with a similar triple feel, I found examples of these online, and sent them to Anindo, whereby he quickly understood my conceptual basis for our collaboration which was reinforced upon our meeting in the studio.

Anindo Chatterjee is legendary for his sui generis touch, tone, articulation, expression, superhuman speed and Bach-like improvisational inventiveness and architecture achieving the spiritual yearning of Indian classical musicians to be a conduit for divinity.

Guruji and I met formally during the summer of 2018 when I had intensive private lessons, continuing in 2019 prior to the pandemic. Our personalities blended well, and Guruji expressed great enthusiasm for the quality of my questions together with admiration for samples of my compositions he heard. There was never a thought at the time of my becoming a jazz pianist, something unexpected leading to our collaboration in September 2022.

Similarly, I had interviewed Eliot Zigmund in 2019 because he is the drummer on my favorite Bill Evans Trio and Quartet albums, his exquisitely vibrant skin, metal and wood colors, rhythms and expressions enlivening those sessions, Bill and Eliot sharing a keen awareness of European classical music. Eliot's playing is also the closest to the manner of Jimmy Cobb among the drummers Bill subsequently recorded with, whose subtle style tapestried so profoundly with Evans on Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959).

My extended interview with Eliot paved the way for our collaboration in November 2022, yielding eight albums over three days, including three with raga-like single tracks on "Lullaby of the Leaves," "But Beautiful," and "A Foggy Day."

Studying jazz recordings is a continuing process for musical growth. Last year I realized how the sustained tone cries in the upper half of the tenor saxophone played by John Coltrane clearly come from the alto saxophone style of Sonny Stitt in terms of emotional and technical flavor. If you listen closely you will detect this truth, if somewhat masked. Given how the tenor saxophone sound of Coltrane is arguably the most famous sound in jazz, this amounts to a central insight, revealing origins.

After writing about the Stitt and Coltrane connection, I was pleased to find a confirmation from John Coltrane himself, whereby he stated early in his career with great enthusiasm how Sonny Stitt had the instrumental approach he had been looking for. And around this time, John was playing alto saxophone with Dizzy Gillespie, the different registers and qualities of alto and tenor saxophone being some of the masking referred to.

Another recent jazz insight is noticing how the influence of Benny Goodman on Lee Konitz is just as strong as that of Lennie Tristano. In general terms, Goodman connected to Lee's expressive nature, with Tristano attracting his intellectual energies.

Also related to Lee Konitz is how during one of our many walks together, this one through Central Park, upon relating my attending classes and rehearsals given by Leonard Bernstein while a student at Tanglewood (we also danced alongside each other with our respective partners at a party following a concert, discussing the dance music being played!), Lee shared how they were good friends, at one point being neighbors in Manhattan, noting Lenny was a superb pianist, and how he told Lee the song "Cool" from West Side Story was inspired by Lee's playing. Invited to the preview of the show in Washington D.C., Bernstein rushed into the lobby during intermission to ask Lee, "What do you think?" Indeed, the generalized "jazz" influence attributed to Lenny's score is more specifically the jazz style of Lee Konitz, including the famous opening phrases of the show.

Part of my newly realized recognition of swing was discovering Benny Goodman being as great a jazz artist as anyone, his extreme fame transcending jazz sometimes creating confusion as to his phenomenal artistic accomplishments.

Finding myself recording with Anindo, who I had previously heard with artists like Nikhil Banerjee, Hariprasad Chaurasia and Shivkumar Sharma, and with Eliot, who I had previously heard with Bill Evans, was surreal, of course, together with being fun, challenging and exhilarating.

The biggest adjustment for collaboration was not having frequent, subtle speeding up and slowing down of the tempo like I do with solo piano improvisation, rather staying with a steady tempo for longer stretches of time, effecting both my sense of form and expression rather dramatically. Tempo changes with Anindo and Eliot were more dramatic, also occurring organically.

I still love solo playing, of course, and plan to continue with that, and hopefully record more with Anindo and Eliot, developing upon what we began with, perhaps recording with other tabla players and drummers, too. I'm also thinking of collaborating with a Latin percussionist and a Middle Eastern percussionist.

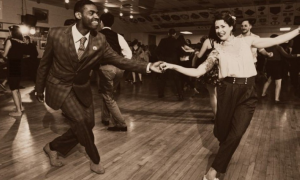

It is the magic of a liberated sound that initially draws us to jazz, where the united spirits of improvisers, composers and lyricists collaborate to triumph over oppression in determined, fearless and joyful form.

*The meruvina is simply music software and hardware working together, and I wouldn't mind at all if other people using similar equipment used the same name, but I know others prefer more technical terms like electronic music, computer music, MIDI, etc. Regarding meruvina, it was my desire to collectively name the musical instruments (software and hardware) I compose for in a manner that reflected the individual way I create music, preferring the simplicity and directness of using one computer and one multi-timbral sound module. Vina is the Sanskrit word for musical instrument, used in a range of South Asian instrument denominations, including the rudra vina (plucked string instrument), and the gatra vina (human voice). I first thought of Compu Vina or Digi Vina, but quickly dismissed those overly technical sounding names. Then I thought to use the initials of my full name, Michael Eric Robinson, and combine them with a Sanskrit or Hindu word or name. Fortunately, I recalled Meru, as in Mount Meru, the heavenly mountain Hindus believe is the center of the universe. Combining meru and vina seemed both poetic and fitting for the ever-developing and seemingly limitless capabilities and potential of the music technology used. Since I compose directly for the meruvina, which may be thought of as an umbrella term or name, and program it to perform my compositions in real time, I am creating both the composition and the performance. This makes me the composer and performer at once, the meruvina being where composition and performance coalesce.

Tags

In the Artist's Own Words

Lee Konitz

Don Ellis

Lalo Schifrin

Ed Shaughnessy

George Harrison

Robbie Krieger

John Densmore

Brian Jones

Ray Manzarek

John Coltrane

Rashied Ali

Morton Feldman

Brian Eno

Bill Evans

Lennie Tristano

Charlie Parker

Béla Bartók

Arnold Schoenberg

frank sinatra

Red Garland

John Cage

Ornette Coleman

Steve Reich

Benny Goodman

Lester Young

Ray Noble

Jimi Hendrix

Eliot Zigmund

Jimmy Cobb

Sonny Stitt

Dizzy Gillespie

Leonard Bernstein

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.