Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » From The Heart To The Hips To The Head

From The Heart To The Hips To The Head

The bridge from the Hips to the Head was constructed by the Beatles in a series of brilliant, transformational albums, beginning with Rubber Soul (1965), Revolver (1966), Sgt. Pepper (1967) Magical Mystery Tour (1967) The White Album (1968) and Abbey Road (1969). These were more than a collection of songs; they were vehicles for exploring and questioning a world gone to hell.

Without deviation from the norm, progress is not possible. —Frank Zappa

The six decades spanning 1920 to 1980 describe more than just a chronological segment in the history of music; they represent a tectonic shift in the Western cultural psyche, mirroring the migration of music's epicenter from Europe to America. The period was one of the most productive and exciting in the history of music. It can be mapped, with quasi-anatomical precision, as a voyage from the Heart to the Hips to the Head. This tripartite structure is a consequence of the evolving relationship between the individual, the society and aesthetics.

This remarkable musical odyssey that spans the tempestuous 1920s to the end of WWII, through the divisive Vietnam War years to the cynical 1970s, reflects the era's volatile moral and cultural norms.

The Heart

The music of the Heart (1920-1945) was primarily a romantic expression of the human condition, and from today's perspective, it was born and nurtured in optimism. The period was dominated by what came to be known as The American Songbook, a body of work that articulated the era's fondest hopes and innocence, tracking, with memorable precision, the intricate, volatile movements of the heart.The Songbook transmuted the creeping anxieties and aspirations of a rapidly modernizing society into a universally accessible music that, through its elegance of form and newly found freedoms, continues to resonate in the present amid contemporary genres like rap and hip-hop that admit to no common ground. Songs like "Night & Day," "Lush Life" and "Sophisticated Lady" rank among the age's great cultural achievements, where the confluence of melody and lyric transformed private pain and joy into universal feelings. The Songbook composers were able to frame heartbreak within a sonic architecture that was both redemptive and cathartic, much as the G in the key of C represents the transcendent or therapeutic interval in 12-bar blues. While owing a debt to the great tradition of Franz Schubert, Johannes Brahms and Gustav Mahler lieder, these composers imposed a metrical and harmonic structure on feelings that produced extended melody lines that have not been surpassed. Compared with their work, most rock and pop tunes—with such notable exceptions as The Beatles and Stevie Wonder—pale. One might propose that this was the last great musical form for which the production of beauty was a sacred duty.

Crucially, the era witnessed the ascendance of jazz and swing, a distinctly the American vernacular that took its cue from the heart worn on the sleeve with virtuosos like Louis Armstrong and Lester Young, and vocalists like Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald giving voice to the era's evolving rhythm and norms. Breaking faith with orthodox classical structures, jazz introduced improvisation into its template, a liberating gesture that prized spontaneity over scripted playing. The music was a mirror to the heart and soul, measured by the complex of feelings it could elicit, whether in the soaring sweep of a wonderfully crafted solo or the intimate confession of a lyric. It vouchsafed the conviction that heartbreak, like grief, was meant to be shared and transcended, and that music's duty was to honor it—and so it did. The music's enduring appeal stems from its capacity to transform both personal pain and exultation into song. With all due respect to the current popularity of mostly monotonic music (rap, hip-hop), The Songbook, to which most jazz musicians return at some point in their careers, confirms that there is no circumventing melody, that it is foundational, and knows no eclipse, and that we are hardwired to seek it out and respond to it.

And I go at a maddening pace,

and I pretend that it's taking your place,

but what else can you do

at the end of a love affair.

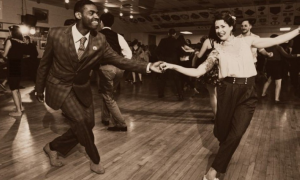

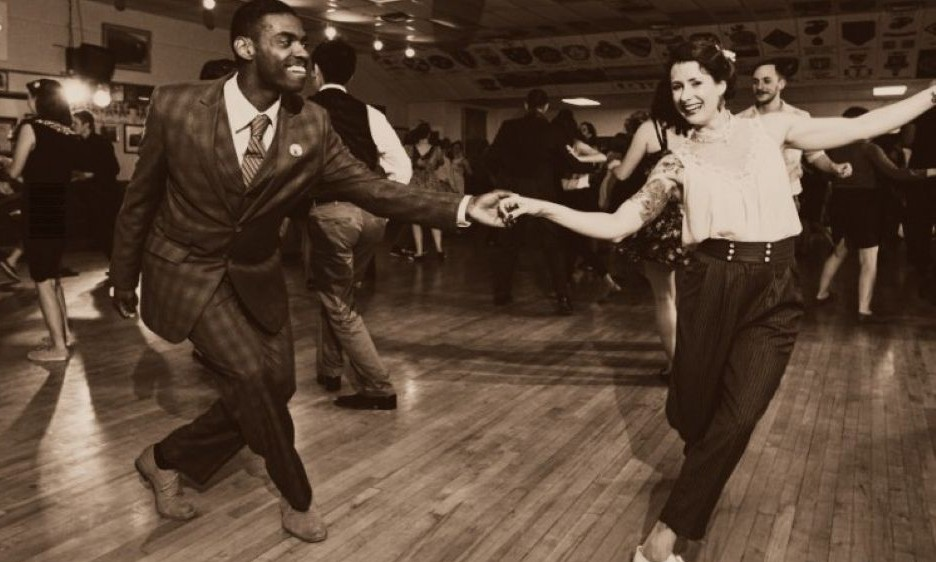

The Hips

Rock and roll emerged in the early 1950s out of a complex interplay of social, musical and technological factors. It emerged suddenly, explosively. The economic prosperity of the 1950s led to the emergence of the teenager —rebels without a cause—as a distinct demographic with their own disposable income and a desire for autonomy. Amid widespread rejection of the era's parental and societal norms, rock and roll became their sonic anthem. The music of the heart, however satisfying as a music experience, did not give the body—the hips—its due. Rock and roll represented a move away from music as a formal, sit-down experience, like a quiet evening of jazz standards, toward music that was participatory, physical and liberating. As an act of both creation and correction, rock and roll brilliantly argued for the supremacy of the body. Its aesthetic was founded on simple chord progressions, seductive rhythms and the untamed energy of youth. Dancing in couples gave way to unstructured, highly individualistic forms of expression.Facilitating the transition from the Heart to the Hips was technology: the invention of the electric guitar and amplification allowed the bass and drum, previously in the background as mere scaffolding, to play a more prominent role. This allowed for a more visceral experience that one could feel as much as hear.

Post WWII teens sought a culture that was separate from their parents' subdued tastes (big band, swing and sentimental pop ballads). The raw energy and driving beat of early rock and roll provided a perfect soundtrack for this rebellion. Dancing became an act of social and physical liberation, challenging the prevailing orthodoxy. The music that emerged through Fats Domino, Chubby Checker, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry and Little Richard took not only America but the world by storm. Elvis's iconic, sexually explicit hip-swiveling was the perfect metaphor for this very shift. The music was exPresley provocative, a direct affront to conservative America.

Rock and roll was also socially liberating. In the spirit of unprecedented inclusivity, both blacks and whites were able to share the same spaces through the shared experience provided by the music. The music of the Hips, if only temporarily, dissolved the arbitrary divisions of race. If the end goal was to feel good, rock and roll provided like no other music, leaving no one behind in its rhythmic wake.

No surprise that rock and roll was met with a tsunami-like backlash. Conservative elements feared the very fabric of American life under threat. Segregationists were alarmed by the unprecedented mixing of the races while the moral majority feared a complete breakdown of sexual mores. Rock and roll was accused of inviting lust and sexual profligacy. Main Street was losing control over the young who were constructing their own narrative. However, every attempt to suppress rock and roll only made it more exciting, generating a generation of "rebels with a cause," a social pivot which became part of is mass appeal. Over and against an increasingly conformist society, rock and roll provided an alternative world that forever changed the world. The Hips reigned supreme, providing a generation with temporary respite from the demands of the adult world. As it turn-tabled out, rock and roll, as a historical interval, was the bridge between the Heart and Head.

The Head

Music, like any life form, never stands still; it is constantly evolving, seeking new ways to capture the spirit of the age. In a mere five years, in what was arguably the most seismic shift in the history of music, the new zeitgeist, led by the Beatles, incorporated a radical reassessment of long held values into songs that demanded the listener's full attention.The bridge from the Hips to the Head was constructed by the Beatles in a series of brilliant, transformational albums, beginning with Rubber Soul (Parlophone, 1965), Revolver (Parlophone, 1966), Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (Parlophone, 1967) Magical Mystery Tour (Parlophone, 1967) The White Album (Apple, 1968) and Abbey Road (Apple, 1969). These were more than a collection of songs; they were vehicles for exploring and questioning a world gone to hell. The period, infamous for its reliance on psychedelics, saw music as a conduit for exploring altered states of consciousness. The concept album was born. Music was meant to be listened to, not just heard. "Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds" became emblematic of the new consciousness, which was less about dancing and more about mind-altering experiences.

If there was a moment that encapsulated Head music, it was captured by The Doors during a performance of "The End" at the Whisky A Go Go in L.A. The song, a bleak journey into the subconscious, had a running time of 11 minutes. During the performance, the entire venue came to a standstill: the go-go girls stopped dancing, as lead singer Jim Morrison, allegedly under the influence of LSD, launched into a haunting, improvised long day's journey into the "end of the night." The effect on the listener and the era was immediate and profound. The music was no longer a backdrop for fun and dancing; it was a direct—at times theatrical, confrontational—invitation to explore the darkest corners of the psyche. "You're the Girl of My Dreams" morphed into "You're Lost Little Girl" (see YouTube video below); "What a Day for a Daydream" mutated into "Strange Days Have Found Us."

Head music went to the top of the charts and stayed there for a decade and a half, producing music that has not been surpassed. It was a music that seemingly exploded out of the void. Every group was its own radical precedent, with its own sonic DNA. Groups like The Doors, Cream, Jefferson Airplane, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Mothers of Invention and Pink Floyd constructed a new musical language that was so compelling that it captured the attention of the jazz world, giving rise to fusion. In the hands of Miles Davis, Weather Report and John McLaughlin, brilliant musicianship merged with the rhythmic power of rock, providing for extended improvisations.

But alas, being hyper-aware, a state of mind abetted by LSD, mescaline or psilocybin, could not be sustained. The psyche's capacity for hard truth is finite, especially unpleasant truths that music cannot change. The surfeited mind had to be shut down.

Supplying the deficit, and mindful that there is no escaping the body, disco became the rage in a counter-revolutionary return to the mindless movements of the Hips. Meanwhile, rock began to serve another purpose: it turned heavier, louder, incorporating more distortion into its template, and with sledgehammer effect, pounded the brain until it shut down. The brain, blissfully relieved of the turmoil and confusion of the world, loved it, could not get enough of it. Music as a pharmaceutical had found its voice. From Black Sabbath to Metallica on to Cannibal Corpse and Nine Inch Nails, heavy metal morphed into death metal, doom metal: all were major, and a marvelous assault on consciousness. Both disco and heavy metal constituted the ultimate betrayal of the Head, willfully rejecting the consciousness Head music sought to raise to preeminence.

Where to? What next? Music is constantly evolving and many of its forms, however uneasily, have proven they can coexist, that there are audiences for those for whom the heart cannot be stilled, for those who look to music to let their bodies talk, and for those who are uncompromising in wanting to see the world in all its good, bad and ugly. Perhaps the next challenge will be to produce music that accommodates all three movements: the Heart, Hips and Head, recognizing that none is equal to the whole. If we all, however subconsciously, look to music as a form of healing, asking it to supply whatever deficits we carry in life, deficits that change as we grow out of our teens into adulthood, middle age and the twilight years, the demand will inevitably produce the product, which is why music never stands still. Perhaps the next great music form will reconcile all disparate musics into a unified whole, allowing the chronically fragmented self to be whole, at least for as long as the music plays.

Which is to say, when all is said and sung, music might bring us down but it never lets us down.

Tags

Opinion

Robert J. Lewis

The Beatles

Stevie Wonder

Louis Armstrong

Lester Young

Billie Holiday

Ella Fitzgerald

Fats Domino

Chubby Checker

Elvis Presley

Chuck Berry

Little Richard

Doors

Jimi Hendrix

The Mothers of Invention

Miles Davis

Weather Report

john mclaughlin

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.