Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » Improvisation Versus Composition

Improvisation Versus Composition

Given what Mozart initially improvised in his head and what he later wrote out are one and the same, the listener will derive equal satisfaction listening to Mozart spontaneously invent at the piano, which is the method of jazz, or perform the composed version of the same

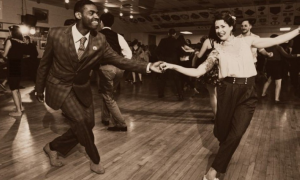

We know at the turn of the 20th century, in New Orleans, musicians, rather suddenly, developed a liking for improvising. Why did playing it safe or reading from the page fall out of favor, resulting in the advent of an entirely new genre—jazz (and blues) —which represented a new way of thinking about music?

So exciting and unexpected were the compliance and respect accorded to improvisation that the standards, from 1920-1950, most of them written for musicals, were taken over by jazz where they have arguably received their most memorable and lasting treatment. More recently, while much has been written about the influence of rock on jazz (and not the other way around) resulting in the birth of fusion, rock music, especially in its heady early years and directly influenced by jazz, incorporated the equivalent of the jazz solo into its template. In the hands of its most gifted proponents—Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Carlos Santana)—the high octane improvised solo became the focal point of every rock concert.

To better understand the challenges, possibilities and limitations of improvised music, let us imagine we have read a life-transforming book that we want to recommend to everyone we know. So we call (or text) our family members, then our circle of friends, and to the best of our ability we try to make the case why they should read the book. If we agree that practice does indeed make perfect, the language and arguments we bring to bear in our recommendation will improve from one call to the next. We note that prior to every call, we know what we are going to say, but we don't know exactly how we are going to say it. However, by the time we have recommended the book 20 times, we will have weeded out the least persuasive arguments and will be following a somewhat fixed order of presentation as it concerns the development of our ideas. Because they cannot be improved upon, over time, we may find ourselves repeating certain turns of phrase and locutions, and even entire sentences verbatim. However, at the end of the day, we will acknowledge that no matter how eloquently we express ourselves in speech, speech cannot compete with the written version of the same. Even the most eloquent of speakers must concede that whatever they write will invariably be more polished and refined than what he has said because he will have had time to ponder over, rewrite and improve each and every sentence, a luxury spontaneous speech does not permit.

By analogy, when musicians begin a solo, they know in general what they want to play (the theme or motif they will be re-interpreting), but they do not know how they are going to play it. But like the recommender of the book, after 20 rehearsals they will have a better idea of how the solo will unfold. Over time, they may become settled on the general ideas they wants to develop, and they might even repeat certain sequences of notes from one performance to the next because they deem them just right.

And like the speaker who decides to write out a recommendation, if musicians decides to turn their impromptu solo into a composition, it will be an improvement over the improvised version because they will have been able to revise certain passages, deselect inferior ones, pay more attention to the harmonic structure, and more effectively connect their ideas.

We take it for granted because the outstanding musician makes it seem so easy, but since every solo has a beginning, middle and end, every improvisation can be likened to a song that has been composed on the spot—a daunting challenge under the best of circumstances. It was not for nothing that Cyrus Chestnut, during a Montreal Jazz Festival performance, began by reminding his audience that jazz is playing music without a chance to edit. Since he did not explain what he meant—unless his concert was meant to be the answer —there are two possible conclusions to be drawn from his statement: that composition is superior to improvisation because it can be worked on and perfected; or playing music without a chance to edit is much more difficult and demanding than reading from the page.

Esteemed jazz critic André Hodeir writes:

"A succession of improvised choruses cannot be expected to have as perfect a degree of continuity as a composition that has been long laboured over and constructed in a spirit that we have seen to be foreign to jazz . . . . many recorded improvisations suffer from a lack of continuity that becomes overwhelmingly apparent upon careful and repeated listening."

If, as Hodeir implies, composition is superior to improvisation (composed music is more likely to pass the test of time), does that mean improvisers are more slothful than the composer, or are they simply confessing to their limitations —that they play better than composes and wisely stay within themselves? Perhaps the improviser (de facto daredevil, adrenalin addict) is fascinated by the thrill and challenge of winging it on the spur of the moment, convinced that repeating the same music over and over again must at some point terminate in the equivalent of musical sclerosis. Now in defense of jazz André Hodeir writes:

"Working out has at least two considerable disadvantages. As concerns creation, if it takes the place of pure improvisation, it may lead to a routine manner and, consequently, to sterility. It brings about a deplorable change in the attitude of the creator, who begins to favour a certain security and stops playing for his own satisfaction . . . How can you believe in a chorus that someone is playing in the selfsame way for the hundredth time? . . . It is hard not to cherish a preference, at last secretly, for the miracle of perfect continuity in a burst of pure improvisation."

Which is why most solos (thankfully) come and go and Mozart is forever.

When someone speaks extemporaneously or plays without notation, could it be that it is the ability to be (without props) so consummately eloquent and persuasive on the spur of the moment that amazes? Which makes the accomplishment akin to a high-wire act. When jazz musicians get together, the challenge is always the same: let us see what we can come up with tonight, and, perhaps recalling an exceptional performance, endeavor to surpass ourselves.

However, we must tread carefully as it concerns the blurry and often madly inspired line where improvisation and composition intersect. When Mozart, sitting on a bench in Vienna's Stadtpark, invents a sonata in his head, the entire piece, from beginning to end, has been improvised. From one note to the next, he does not know where he is going until he is there, following an internal logic that is so correct that every note seems to be the inevitable outcome and answer to the preceding note, which is why he never had to revise. When later, he writes out what he has created in his head, it becomes composition. Given what Mozart initially improvised in his head and what he later wrote out are one and the same, the listener will derive equal satisfaction listening to Mozart spontaneously invent at the piano, which is the method of jazz, or perform the composed version of the same. But of course Mozart is sui generis, and for many proof of the existence of God.

What the jazz lover cherishes in an improvised solo are those exceptional moments of invention that would not be changed if they were written out as composition, which is why certain solos or sections of them achieve the status of song or composition —and this is especially true in rock: think of early Santana or Robby Krieger in "Light My Fire." These represent the unsurpassed moments of improvised music around which audiences gather, and invariably leave somewhat disappointed, since most solos are patently forgettable and deserving of the oblivion that awaits them.

Allowing that there is a little bit of Mozart (perfection) in every distinguished jazz musician, most jazz concerts will satisfy to a certain extent, especially if we lower our expectations and recognize that as listeners, what in fact draws us to jazz is not only the emotional intelligence that causes a certain sequence of notes to come into being, but the musician's remarkable ability to perform without a script, to persuasively tell a story that has never been told before. And of course knowing that the improvisers—at any time —can drop the ball and embarrass themselves lends to every jazz concert a certain edge and excitement that is unique to the genre. Fred Hersch has famously stated that if he feels he is playing well 30% of the time, he considers it a successful performance. Jazz is the Formula I of music.

Human beings are a diverse, unpredictable lot and it is only natural that some prefer composed music while others prefer improvisation. Which is why arguing for the superiority of one genre or style of playing over another is perhaps not only beside the point, it is to completely miss the point if the world is richer for having both forms of music in its library, and enthusiastic audiences for both.

If we are lucky enough to count music as one of the privileged forms through which we travel in our unceasing quest to find meaning and purpose in life, it is surely the variety and beauty of the world's library, and not how it gets made, that is of significance and reason to be thankful.

Or to take a page out of Plato: "Music is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, and charm and gaiety to life and to everything." Yes, music can bring us down but it never lets us down.

Tags

Opinion

Robert J. Lewis

Fred Hersch

Jimi Hendrix

Frank Zappa

Jimmy Page

Carlos Santana

Robbie Krieger

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Mozart

Montreal Jazz Festival

jeff beck

New Orleans

CYRUS CHESTNUT

Andre Hodeir

Plato

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Fred Hersch Concerts

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.