Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » Listening To Music On Its Own Terms Fallacy

Listening To Music On Its Own Terms Fallacy

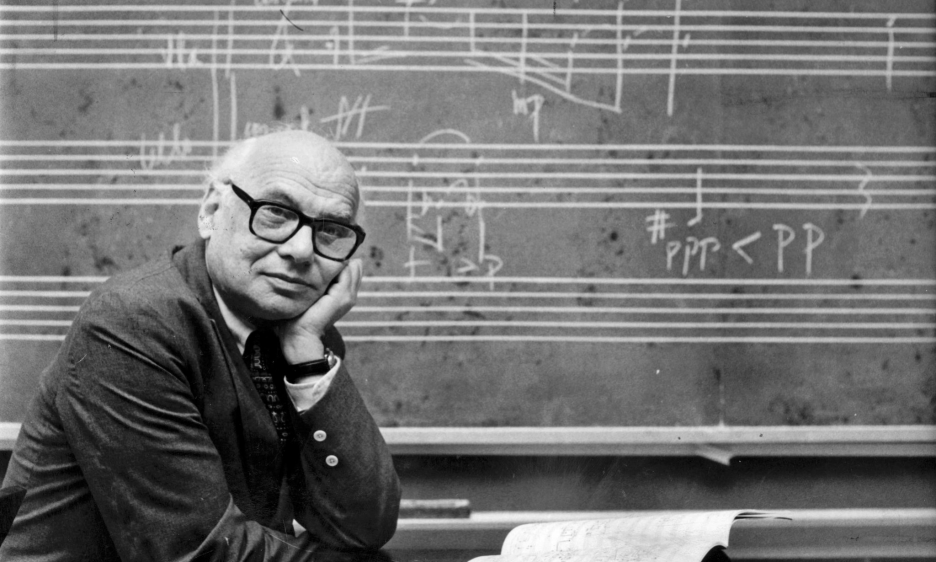

Courtesy Keith Meyer, The New York Times/Redux

Music is not a mathematical equation, nor a scientific law, where a singular, incontrovertible solution exists. Nor is its meaning hermetically sealed within its structure. The meaning of music is a continually shifting dynamic...

It sounds straightforward, but the accusation is packed with all sorts of tangled ideas about what a listener's job is, and whether art has some kind of fixed value.

When the composer speaks of having to listen to music on its own terms, he invariably conjures a specific, often rigid, paradigm of engagement: that there exists but one perfect, unassailable method by which to apprehend the music, a method precisely calibrated to align with the creator's original intent. Such a premise elevates the composer to the role of an unquestionable arbiter, the ultimate authority on both meaning and merit. The audience, by this decree, is reduced to a passive receptacle, tasked solely with absorbing and appreciating the work precisely as it was meant to be absorbed. Any deviation from this prescribed path, any personal interpretation or spontaneous reaction, is dismissed as a fundamental misapprehension, a failure to truly 'get it.'

The accusation rests upon a dubious foundation of unexamined assumptions that more often than not create an unbridgeable chasm between the creator's aspiration and the audience's lived experience.

Foremost among these is the curious notion that music, by some inherent, objective decree, possesses a set of immutable rules governing its reception and comprehension. Should audiences, through some perceived intellectual or aesthetic deficiency, fail to grasp or connect with these predetermined elements, the fault is laid squarely at their feet. The unspoken corollary is that a more astute, more attuned audience would instantly recognize the music's inherent worth, thereby propelling it to its rightful place in the pantheon of popular acclaim. This convenient transference of blame, from the artistic creation to its intended recipient, is akin to asserting that a joke's failure to elicit laughter stems not from its inherent lack of humour, but from the audience's ignorance of complex comedic theory.

The second, equally specious, assumption posits the composer as the sole arbiter of the music's meaning and intrinsic worth. The music, in this worldview, becomes a direct extension of the composer's inner world, his feelings, and its essence can only be truly apprehended by those who align their listening perfectly with his initial creative impulse. The inconvenient reality of the audience's actual experience, its subjective response, is thus conveniently relegated to irrelevance.

This is a classic maneuver of blame-shifting, with the burden of failure cast squarely upon the shoulders of the listener. Should a musical work fail to captivate, to resonate, to achieve popular success, it is not because it is impenetrable, tedious, or simply ill-conceived. No, the deficiency resides within the audience itself, lacking in patience or simply too obtuse to grasp its merit.

Such an assumption often compels composers into a defensive posture. When their creations are met with critical indifference or, worse, outright neglect, they may resort to accusing the audience of cultural illiteracy or a lack of musical erudition. This engenders a false dichotomy between serious music and popular music, wherein the former demands a specialized mode of listening that the latter, by its very nature, does not. The music's unpopularity is thus transmuted into a perverse badge of honor, a testament to its supposed profundity. This convoluted reasoning conveniently absolves the composer, even in the face of universal apathy, by attributing failure to the audience's perceived shortcomings rather than to his own creative choices.

Furthermore, the complaint often proceeds from the premise that listening to music, particularly that which is deemed complex or experimental, is primarily an intellectual or technical exercise, rather than a visceral or emotional encounter. This perspective places undue emphasis on intricate structures, theoretical underpinnings, and the composer's technical prowess. It suggests that genuine appreciation can only be attained through a rigorous deconstruction of these elements. The raw emotional impact, the sheer unadulterated pleasure, or the profound personal connection that music can forge are, in this view, dismissed as secondary.

This intellectual conceit risks alienating those who approach music primarily for its affective power, for its inherent beauty, or for its capacity to foster a shared human experience. Should the composer insist that his music can only be understood through a labyrinthine technical analysis or by decoding abstruse intellectual puzzles, he erects an insurmountable barrier for all but the most rigorously trained musicians or theorists. The spontaneous, the intuitive, the emotionally driven response to music is deemed somehow deficient or illegitimate.

Music is not a mathematical equation, nor a scientific law, where a singular, incontrovertible solution exists. Nor is its meaning hermetically sealed within its structure. The meaning of music is a continually shifting dynamic between the composition, the performer who breathes life into it, and the listener, who brings to the encounter a unique tapestry of life experiences, cultural background and, not to be short-shrifted, his current emotional state.

A single piece of music possesses the remarkable capacity to affect disparate listeners in myriad ways, each equally valid. "None of us is a hypocrite in our pleasures," observes La Rochefoucault. One may derive profound satisfaction from the intricate counterpoint of a classical fugue without ever consciously dissecting its architecture, just as another may be deeply moved by a simple melody without comprehending its underlying chord progression. Music, by its very essence, is an open category, profoundly personal and endlessly expansive.

Our personal communion with a song, the memories it conjures, the involuntary physical response it induces—these are all legitimate, indeed vital, avenues of experience.

What once seemed audacious, even avant-garde in one epoch, may, with the march of time, become utterly commonplace, even quaint, in another. Audiences across generations cultivate novel listening habits, develop new aesthetic sensibilities and discover fresh modalities of connecting with sound. To demand that contemporary listeners approach historical music solely through the eyes of its original era is an exercise in futility. Music evolves, and with it, so too do we. As we accrue the wisdom of years, our perspectives broaden, which often explains why the music that once moved us no longer resonates with the same intensity. The allure of music resides precisely in its capacity for reinterpretation, its perpetual rediscovery by each new generation. It is a dialogue across the ages, not a fixed, immutable pronouncement. There is nothing more exhilarating than a piece of music that challenges our preconceived notions, compels us to engage in a novel manner, or simply engulfs us in an unexpected torrent of emotions.

This is not to suggest that all music must be immediately accessible or universally adored. Far from it. However, a robust artistic environment necessitates a broad spectrum of engagement, from the casual enjoyment of a fleeting melody to the rigorous intellectual pursuit of academic study, without invalidating any segment of that continuum. The true objective ought to be the invitation of listeners into the artistic conversation, not the erection of intellectual barricades. The profound beauty of music lies in its inherent universality, its unparalleled capacity to transcend linguistic and cultural divides, and to stir the human spirit. Music is a bridge between the creator and the listener, and when that bridge is sundered by an insistence upon intellectual purity, all parties suffer.

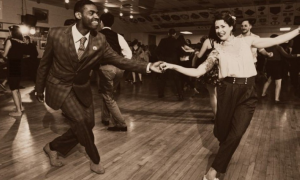

What resonates with one individual may fail to stir another. We are, each of us, products of disparate backgrounds, possessed of unique aesthetic predilections, seeking varied experiences from the world's music. Some crave intellectual stimulation, others the primal urge to dance, some seek solace and relaxation, while still others yearn for profound challenge. The magic of music resides in its boundless capacity to offer something for every soul. Music, at its heart, is a conversation, which, by its very nature, demands an openness to all perspectives.

Which is not to say that exceptional, high-quality music may be unjustly overlooked or entirely ignored, not due to any inherent flaw in its composition, but because the audience lacked the requisite tools for its appreciation. On far too many occasions, discerns Samuel Johnson, "the first appearance of excellence unites multitudes against it." Consider a groundbreaking work of avant-garde jazz presented to an audience whose entire musical diet consists of the saccharine offerings of pop radio or monotonic rap. Such listeners may simply lack the ear (musical vocabulary) to grasp the unfamiliar genre, its unconventional harmonies and unorthodox structures. In this case, the music is not deficient but rather the listeners have yet to develop the necessary categories of discrimination required to engage with something profoundly divergent from their accustomed fare. It is akin to expecting a devotee of comic books to readily apprehend the intricacies of a philosophical treatise. Genuine innovation frequently outpaces immediate public comprehension, leaving truly visionary works to languish in obscurity, awaiting discovery and celebration by future generations.

Another conceit is the composer's facile conclusion that his music's lack of popularity is evidence of its profundity, while popular music is dismissed as inherently shallow or commercially compromised. Thus, commercial success is perversely recast as the antithesis of artistic merit, and obscurity is celebrated as the very hallmark of excellence. Yet, the mere absence of popularity does not, in itself, confer artistic merit. A significant portion of music remains unpopular precisely because it lacks compelling musical ideas, is poorly executed, or simply fails to offer a meaningful experience to the listener.

Cultural distinctions play a crucial role in the reception and valuation of music. A foundational musical interval or rhythmic pattern (e.g., flamenco, Indian raga) in one cultural milieu may prove utterly alien or devoid of meaning in another. Composers who operate within the confines of specific cultural or academic traditions ought to temper their expectations regarding the universal reception of their work by global audiences.

Music is often lauded as a universal language, yet like any language, it possesses dialects, accents and cultural idioms that demand comprehension for true appreciation. The driving power of music resides in its capacity to bridge these cultural chasms, not to reinforce them. It is about forging common ground, not imposing a singular worldview. And that demands an open mind from both the creator and the listener.

True genius resides in the creation of something impactful, irrespective of whether it is apprehended by millions or by a dedicated few. The true measure of art is not its market valuation, but its intrinsic power to move, to challenge, to inspire and to withstand the test of time.

The pursuit of art ought to be a journey, not a retreat into the comforting echo chamber of self-congratulation. Communication, by its very essence, necessitates an audience, however modest in number, however long it may take to cultivate.

Music is not consumed in a vacuum; it is experienced within a complex dynamic of cultural norms, societal conventions and individual circumstance. Music is inextricably woven into the fabric of our lives, our celebrations, our sorrows and especially our often messy relationships. ("And I go at a maddening pace, and pretend that it's taking your place, but what else can you do at the end of a love affair.")

But through thick and thin music is always there for us, as a shared joy and moveable feast.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.