Home » Jazz Articles » Highly Opinionated » Roswell Rudd: The Musical Magus Turns 75

Roswell Rudd: The Musical Magus Turns 75

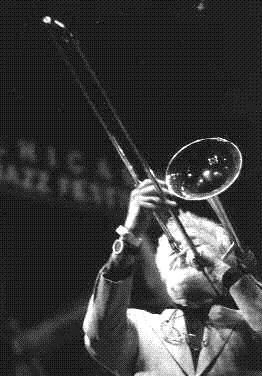

I see him suddenly as if in a dream. His eyes are somewhat cynical, questioning and beautiful. Wrinkles of laughter pucker up at the edges, and he reminds me of my father. His smile disappears as the mouthpiece of his gleaming trombone meets his lips. Then, all I can see is the large bell of the 'bone. His eyes widen. He sucks in a great gust of air. It seems to settle in his powerful lungs. Then the first sounds emerge. Slow, controlled notes seemingly suspended in the air. I am transfixed. His body sways and bends backward as he squeezes he notes out of his mouth... out of the 30 feet of brass pipe and out of the bell of the horn. The unique smears and near vocal arpeggios that are woven into the dyed musical fabric of "Circulation" dance maddeningly as they unfurl in diaphanous splendor, chorus after chorus, until the rest of the orchestra—too restless from comping behind him—join, bleating and crying as they dance to his magnificent solo. I am transfixed and as I listen the song's barely visible characters take shape before my eyes.

The mighty dramaturgy of Roswell Rudd's sinewy, restless music had an immediate effect on me. He does not let up, even as he brings his music to a close. I watch as the notes take shape and fill out with tone and color... shades of warm rusts and yellows... greens, reds and bIacks... I watch as the notes pirouette in the air above me. The spectacular unfolding of timbre as each instrument interacts with the other—horns and reeds, strings, piano and percussion, and most of all Rudd himself, whose trombone has always been suggestive of the human voice as it carved the air with monumental musicianship.

Rudd's sense of drama is matched by his razor-sharp sense of where he belongs in the world of sound. Nowhere is it more vivid and audible as when he weaves in and out of tubaist Howard Johnson's visceral playing on "Breath-a-Howard..." The masterly conversation between Rudd and Johnson is truly worthy of the musical adventure that is created as Rudd plies his art alongside Johnson's tuba. What a magnificent, soaring dialogue born of Johnson's superb narration of a story, aided and abetted by Rudd, as the rest of the band pick up the cue from Hod O'Brien's fingers on the ebony and ivory. "Breath-a-Howard" awakes like the great gusts of wind in a powerful hurricane. Then...silence...

The whispering of the 1-2... 1-2-3 splash across the cymbals... Beaver Harris is caressing and back-slapping the skins of his toms and tympani. He repeats a cycle then he crunches the high-hat. Nobody moves... except Sheila Jordan, as she slides into position to sing. Then she wails with the band, and the song becomes "Lullaby for Greg." The tears are streaming down my face. This has much to do with Jordon's lyrics and her vocals, but none of that would matter if it were not for the aching beauty of the music itself. Unashamed am I and moved by it all. This is as close to the perfect knot of emotion that will ever grab hold of my gut. Somehow I get this way when I listen to Roswell Rudd.

The whispering of the 1-2... 1-2-3 splash across the cymbals... Beaver Harris is caressing and back-slapping the skins of his toms and tympani. He repeats a cycle then he crunches the high-hat. Nobody moves... except Sheila Jordan, as she slides into position to sing. Then she wails with the band, and the song becomes "Lullaby for Greg." The tears are streaming down my face. This has much to do with Jordon's lyrics and her vocals, but none of that would matter if it were not for the aching beauty of the music itself. Unashamed am I and moved by it all. This is as close to the perfect knot of emotion that will ever grab hold of my gut. Somehow I get this way when I listen to Roswell Rudd. Dewey Redman, tugging at notes, now... as Jordan takes a break. He meets them halfway inside his deep guts, caresses them and tosses them in broad glissandos—soft-loud... loud-soft—then a fast arpeggio, as he seems to lick his lips. Hands flutter and flash on the triangles and a muted cowbell... William Godvin "Beaver" Harris is on song! Remembering waking, wailing babies at Gorree. Charlie Haden's fingers are flickering across the gut-stringed bass violin... Its thunder rumbles from the depths of its throat. Sirone follow suit. Dewey Redman breaks in suddenly. He lets out a series of ululations and shrieks a long and winded shriek. Then he tosses a high C wildly upward. It flies out of the bell of the horn and into the air spinning like a top and dissipates softly in an after burn.

Roswell Rudd and The Jazz Composers Orchestra playing Numatik Swing Band (JCOA, 1973), a suite of majestic compositions commissioned from Rudd in 1973 became my baptism by the trombonist and left such a profound impact on heart and soul that it echoes in my mind's ear. Four decades on, the profundity of the music—its aching melodies and sophisticated harmonies—is what truly classic music is all about... scintillating, enduring and utterly memorable. I told him that, when we spoke about a year ago, as I was preparing to honor him when he turned 75. But he was being characteristically modest. In actual fact there is much more that he gave the world of contemporary music. I discovered that when I looked deeper into his masterly repertoire that I first heard when I bought a copy of saxophonist Archie Shepp's Mama Too Tight (Impulse!, 1966), that same year.

Roswell Rudd and The Jazz Composers Orchestra playing Numatik Swing Band (JCOA, 1973), a suite of majestic compositions commissioned from Rudd in 1973 became my baptism by the trombonist and left such a profound impact on heart and soul that it echoes in my mind's ear. Four decades on, the profundity of the music—its aching melodies and sophisticated harmonies—is what truly classic music is all about... scintillating, enduring and utterly memorable. I told him that, when we spoke about a year ago, as I was preparing to honor him when he turned 75. But he was being characteristically modest. In actual fact there is much more that he gave the world of contemporary music. I discovered that when I looked deeper into his masterly repertoire that I first heard when I bought a copy of saxophonist Archie Shepp's Mama Too Tight (Impulse!, 1966), that same year. Shepp had, in that one seminal album, almost singlehandedly created a snapshot of African-American history. In its title track, for instance, the composer created one of the most sterling tributes to the central familial figure in society, deconstructing the socio-political setting in which generations of African-American youth grew up, keeping the culture alive. In doing so, Shepp deconstructed the blues with the burbling flow of his glorious tenor saxophone. Rudd played counterpoint when he was called to do so. But what he also did, when he punctuated his visceral playing with almost vocal shouts and guttural smears, was to create a primordial cry of the human being tortured, yet emerging triumphant from his endeavors; an artist who reached—body and soul—for the seemingly unreachable... falling, getting up, falling again and again, until finally reaching out and grabbing at life's Holy Grail. Rudd was already a part of the great revival of contemporary American music. A torchbearer alongside Shepp and Grachan Moncur III, Charlie Haden and Beaver Harris, and every other musician whose spirit the musicians on that record were keeping alive.

It is easy to think of an artist in the vanguard of musical revolution as being rambunctious, sometimes wayward, overly sentimental and even lost at times. But not Roswell Rudd. A premier composer and instrumentalist throughout his long and stellar career, Rudd has always had an acute sense of his place in the history of American music. Completely cognizant of its European, African and American folk roots, he has emerged over time steadily like a verdant outgrowth of music's enormous tree of life. He seems to have enjoyed the flowering of ragtime, Dixieland and swing and making this rewarding period of musical development an inherent part of his compositions... Although Rudd may seem to have missed the bebop era altogether—something that the ever-present Janice "Ms. JJ" Johnson did—he (Rudd) did forge an alliance with the music of one of its great pioneers, Thelonious Monk. In addition, Rudd actually played on several occasions, but sadly never recorded, with the other great composer and pianist of that—or any other—period in time, Herbie Nichols. The association may have resulted in Rudd reaching terminal velocity as a writer. He and an old friend, Steve Lacy, together began to revive the music of those two pioneering pianists (until Lacy's untimely death in 2004) in some of the greatest repertory music ever made, with several bands, over the years.

However, almost unacknowledged even by the cognoscenti, Roswell Rudd had been clearing a path in history all his own. It was only understandable as Rudd had, in every sense of the word, been in the centre of contemporary American music from the first few decades of the 20th Century itself. His music has disregarded the obvious differences in geography and genre, and traversed generations from the early days of Dixieland until today. The reason is that Rudd has—almost alone—been a sublime melodic alchemist, singing with "mammalian" grandeur of the tragedy and ultimate triumph of human endeavor.

However, almost unacknowledged even by the cognoscenti, Roswell Rudd had been clearing a path in history all his own. It was only understandable as Rudd had, in every sense of the word, been in the centre of contemporary American music from the first few decades of the 20th Century itself. His music has disregarded the obvious differences in geography and genre, and traversed generations from the early days of Dixieland until today. The reason is that Rudd has—almost alone—been a sublime melodic alchemist, singing with "mammalian" grandeur of the tragedy and ultimate triumph of human endeavor. In the beginning, Rudd was merely an observer, a keen one, no doubt, in the history that surrounded him. He grew up in a home filled with music. His father was a drummer and his mother taught remedial speech therapy and championed opera, especially Gilbert and Sullivan. When not listening to jazz, the popular music of the day on the radio, Rudd took in performances by the stride pianists. He remembers attending one featuring pianist, James P. Johnson and bassist, "Pops" Foster when he was 12 years old. A few years later, when he was fifteen, he was first mesmerized by Louis Armstrong, who performed during the intermission of the 1952 movie, The Crimson Pirate. Rudd returned to see the movie three times just to listen to Armstrong.

What attracted the young trombonist to the great pioneer of American music was not just his trumpet playing, which had a seductive, primordial quality to it, but also Armstrong's vocals. The trumpeter was not only a monumental instrumentalist, but he was also one of the foremost interpreters of song. A mighty vocalist, Armstrong had an innate ability to tell a story and had an inimitable sense of phrasing, at the cutting edge where the human voice met the art of song. There were other vocalists who stole Rudd's heart away. Duke Ellington Orchestra alumnus, Al Hibbler was one; the others were Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald—all voices who not only defined the music of the day, but ignited the planet as well.

This ability to literally let his trombone melt into the cadences of the song is what characterized Roswell Rudd's playing right from his earliest playing and his earliest associations with musicians. In the early 50's Rudd attended Yale University and was part of a music ensemble, Eli's Chosen Six. The band recorded a seminal album for Columbia entitled Eli's Yale University Dixieland Band (Columbia, 1955). Another album with the band appears to have fallen off discographies almost everywhere and is likely to remain so. Rudd did revive the band briefly during his 70th year celebrations with a performance at the Rubin Museum of Art in 2002. From the very beginning of his vocation in music, Rudd's tonal vocabulary has included growling cries, smears woven into the lyrical wow and flutter of his playing that is so eternal that it seems to come from some of the oldest sounds on the planet—the creaks and grumbles and tremulous vibrations that emerge from the nebulous soul of the earth.

For someone who was so connected to the hymn of the universe, it seems fortuitous that Rudd should come to be associated with Alan Lomax, one of the seminal figures in American music. From the early '60s, Rudd worked off and on as a research assistant with Lomax. This culminated in his involvement in two monumental projects. The first was the Cantometrics Project, a global song-style endeavor that sought to study how all folk music traditions are linked in some way. The designers of the project used 37 parameters to analyze the recordings of folk music that they made over the years. Rudd was in his element academically here, working with Lomax who had first spoken of Cantometrics. The ethnomusicologist first formulated this method of studying social interaction through the study of folk music. Lomax attempted to relate the statistical analysis of sonic elements of traditional music, or folk songs, to the statistical analysis of sociological traits. He did this by finding ways to link the vocal quality of folk music—color, timbre, normal pitch, attack and type of ornamentation—to all of human character within a social context.

Despite the part-time nature of Roswell Rudd's association with this project, the trombonist seems to carry on and live the premise of the project in his music in the most innate sense. His music, both monophonic and polyphonic, explores a dramatic spectrum of color. In the gutbucket manner of his exploration of the trombone voice with and without his own in tow, he has extended the timbral values of that ubiquitous instrument. Growling up and down the register of the trombone he has stretched the already elastic pitch of the instrument, varied his embouchure and attack with such invention that he has created a whole new melodic ornamentation, something virtually no other trombonist (barring Steve Turre) has achieved on this, or any other instrument.

Despite the part-time nature of Roswell Rudd's association with this project, the trombonist seems to carry on and live the premise of the project in his music in the most innate sense. His music, both monophonic and polyphonic, explores a dramatic spectrum of color. In the gutbucket manner of his exploration of the trombone voice with and without his own in tow, he has extended the timbral values of that ubiquitous instrument. Growling up and down the register of the trombone he has stretched the already elastic pitch of the instrument, varied his embouchure and attack with such invention that he has created a whole new melodic ornamentation, something virtually no other trombonist (barring Steve Turre) has achieved on this, or any other instrument. It was this unique palette of sonic color that first attracted Herbie Nichols to the Rudd. The great pianist forged a close alliance with the trombonist, exchanging ideas and rehearsing and playing together regularly, or whenever Rudd would find them Dixieland gigs. However, the two musicians spent much time together, learning from each other—Rudd more than Nichols. In fact, Rudd credits Nichols for "learning" all about the art of creating unforgettable melody in the bass-line of song, something that Rudd has carried with him throughout his musical life so far. The association also prompted Rudd to create some of the finest repertory music around the recreations of Nichols' music, an achievement that is only matched by similar recreations of the music of that other giant of modern music, Thelonious Monk.

However, much as Rudd puts his unique sound down to hearing the great vocalists, he might as well have included Charlie Parker and the musicians of the '40s as well in that group that influenced his approach to music. Central to all of which was Rudd's existence in every musical aspect of the sociological context. Although his musical output has been steady throughout his life so far, Rudd began to emerge from the shadows and burst onto the scene with his avowed allegiance to the free counterpoint of the '60s. His first foray during this heady period in modern American music came as a member of an ensemble fronted by Cecil Taylor and Buell Neidlinger, a bassist he met at Yale in 1961. The album, New York City R&B (1961), not one of Taylor's best-known, was produced by Nat Hentoff on his short-lived Candid label, but later also released on the Columbia imprint in 1971. It was an album full of textural brilliance with a rich nonet sound to which Rudd brought his characteristically "dirty" trombone.

However, much as Rudd puts his unique sound down to hearing the great vocalists, he might as well have included Charlie Parker and the musicians of the '40s as well in that group that influenced his approach to music. Central to all of which was Rudd's existence in every musical aspect of the sociological context. Although his musical output has been steady throughout his life so far, Rudd began to emerge from the shadows and burst onto the scene with his avowed allegiance to the free counterpoint of the '60s. His first foray during this heady period in modern American music came as a member of an ensemble fronted by Cecil Taylor and Buell Neidlinger, a bassist he met at Yale in 1961. The album, New York City R&B (1961), not one of Taylor's best-known, was produced by Nat Hentoff on his short-lived Candid label, but later also released on the Columbia imprint in 1971. It was an album full of textural brilliance with a rich nonet sound to which Rudd brought his characteristically "dirty" trombone. Twenty years after he heard the harmonic and rhythmic sleight of hand practiced by The Yardbird, Rudd melded the advancements of bebop into his own playing by connecting the dots between bebop and later re-evaluations of it, by quite literally sifting through Parker's vocabulary that arose from European harmonic theoretical foundations melded together with African modal rhythmic ones. All this, of course swirling around in one heated cauldron that included Rudd's own ability to make the voice of human endeavor come alive through his trombone.

By this time, Rudd had all but completed his tumultuous dive into the fecund modern music scene in New York. He forged a highly productive relationship with musicians such as Cecil Taylor, John Tchicai, and Archie Shepp and, most enduring of all, with the soprano saxophonist, Steve Lacy. One of the first records that Rudd came to be recognized was Into the Hot (Impulse!, 1961), a seminal album made by Gil Evans. However, at that time in the '60s it was Archie Shepp who held court in the improvised music scene of that day, who was Rudd's most frequent employer. With Shepp, Rudd made a series of spectacular albums, beginning with Four for Trane (Impulse!, 1964), and also including the legendary set, Mama Too Tight.

The '60s was the first truly active period in Rudd's recording career. In addition to performances and albums he made with Archie Shepp, the trombonist also made his first album of Monk's music with one of his musical soul-mates, Steve Lacy. School Days (Hat Hut, 1963) began what would become the first of many performances of some of the finest repertory music of that (or any) other period in time. Both Lacy and Rudd were great admirers of Monk's music and would continue to play his charts regularly for more than a decade. Rudd would continue to play Monk's music, and later also revisit the music of his other idol, Herbie Nichols. But that first album of Monk pieces shared with Lacy would go on to become one of the landmark albums of its day and be reissued several times through the '70s in Europe, and even as recently as 2011 by the British imprint, Emanem.

During this time, Rudd also formed the New York Art Quartet, a floating outfit that included Tchicai, bassists Lewis Worrell and Reggie Workman, and percussionist, Milford Graves. Bernard Stollman, another seminal figure of that era, preserved some of Rudd's finest music on his ESP-Disk' label. Stollman also released New York Eye and Ear Control (1964), with three stunning tracks on an album that figured in the soundtrack of the eponymous film by the Toronto-based auteur, Michael Snow. This album was one that was led by the great Albert Ayler, but on which Rudd's guttural glissandi feature prominently, almost like a clarion call for that fertile era of improvised music.

During this time, Rudd also formed the New York Art Quartet, a floating outfit that included Tchicai, bassists Lewis Worrell and Reggie Workman, and percussionist, Milford Graves. Bernard Stollman, another seminal figure of that era, preserved some of Rudd's finest music on his ESP-Disk' label. Stollman also released New York Eye and Ear Control (1964), with three stunning tracks on an album that figured in the soundtrack of the eponymous film by the Toronto-based auteur, Michael Snow. This album was one that was led by the great Albert Ayler, but on which Rudd's guttural glissandi feature prominently, almost like a clarion call for that fertile era of improvised music. Just as his voyage of musical discovery began in the '60s, Rudd's epic sonic journey seemed to crest for the first time in the '70s when he made a series of recordings with musicians who shared his sense of adventure. His albums with Charlie Haden, such as Liberation Music Orchestra (Impulse!, 1969) and with Carla Bley, including Dinner Music (Watt, 1977) and Musique Mechanique (Watt, 1979), featured stellar performances by the trombonist. His often aching sound made both Haden's great narratives all the more elementally sad, and his dramatic, sliding leaps created some of the more enduring passages in Bley's superb compositions. During this time, Rudd also made some of his most significant albums under his own name. His first magnum opus, Numatik Swing Band, made in 1973, was followed by Flexible Flyer (Black Lion, 1974), with magnificent vocalist Sheila Jordan, and he also reunited with Steve Lacy to make his other magnum opus, Blown Bone (Emanem, 1976).

During this time, Rudd also began a teaching career first as a member of the ethnomusicology faculty at Bard State College, a fertile stint that began in 1972 and lasted until 1976, when he moved to Maine and taught at the University of Maine between 1976 and 1982.

It was during that decade of the '80s that Rudd seemed to withdraw from active recording, focusing his energy on first teaching and later on composing, practicing and honing his monumental skills on the trombone. Wood-shedding was also combined with an unusual gig. As the performance scene in New York dried up to a smidge, living in the Big Apple became untenable for Rudd and he moved upstate to work in an ensemble at The Granit Hotel, a tourist attraction for retirees from Florida. By his own admission, Rudd played music to back up comedians, singers, dancers and fire-eaters. Years of living the life of an ethnomusicologist, combined with the experience and austere discipline as an assistant to Alan Lomax, Rudd also developed the ability to retain the qualities of a sponge. He listened and absorbed the sounds of humor and the elastic setting in which he existed. This would prove eminently useful as he emerged on the B side of this experience, cresting a new wave—a high he would continue to be on for the next two or three decades.

It was first during the late '70s that Rudd first came into contact with Verna Gillis, another extraordinary ethnomusicologist and founder of Soundscape at a performance that Rudd was involved in, with his wife and his wife. Descending from Upstate New York from time to time Rudd often crossed paths with Gillis and participated in the occasional musical adventure with her. Also, by the time the '90s swung around, Rudd was back on the block, performing and making a series of albums, with the British saxophonist Elton Dean, Rumours of an Incident (Slam, 1996) and, a year later, Newsense (Slam, 1997). Rudd also made all-but-forgotten albums, Terrible NRBQ with Terry Adams (New World, 1996) and Out and About (CIMP, 1996), with trombonist Steve Swell, who he credits with enabling his return to New York City's gradually reawakening music scene.

It was during the '80s, and possibly even before that time, that Rudd began to revisit the music of Herbie Nichols. His fascination and utter devotion to one of the true and unsung geniuses of modern music began to take flight again. Relocating Herbie Nichols' music to the landscape of the trombone, Rudd created one of the most definitive tributes to the pianist and composer. On three days in November, 1996—from the 18th to the 20th—Rudd recorded fifteen charts composed by Nichols in a trio setting that included Greg Millar, on guitar and percussion, and John Bacon Jr. on drums and vibraphone. The small ensemble recast Nichols' extraordinary music with all its written melodic drama, without piano or bass. This bore out Rudd's theory about Nichols, whom he saw as a sublime melodist who enabled that aspect of music to flourish unfettered in the bass line of his music. The Unheard Herbie Nichols, Vols. 1 and 2 (CIMP, 1996 and 1997 respectively) not only enhanced Rudd's reputation as an arranger exponentially, but have also added to Nichols' own repertoire in much the same way as albums by Rudd's old Yale cohort, Buell Neidlinger, Dutch pianist Misha Mengelberg and the music of the Herbie Nichols Project, performed by a group led by pianist Frank Kimbrough. Sadly, however, like most of Rudd's music these two albums have also passed like ships in the night, unnoticed even by some of the musical cognoscenti.

It was during the '80s, and possibly even before that time, that Rudd began to revisit the music of Herbie Nichols. His fascination and utter devotion to one of the true and unsung geniuses of modern music began to take flight again. Relocating Herbie Nichols' music to the landscape of the trombone, Rudd created one of the most definitive tributes to the pianist and composer. On three days in November, 1996—from the 18th to the 20th—Rudd recorded fifteen charts composed by Nichols in a trio setting that included Greg Millar, on guitar and percussion, and John Bacon Jr. on drums and vibraphone. The small ensemble recast Nichols' extraordinary music with all its written melodic drama, without piano or bass. This bore out Rudd's theory about Nichols, whom he saw as a sublime melodist who enabled that aspect of music to flourish unfettered in the bass line of his music. The Unheard Herbie Nichols, Vols. 1 and 2 (CIMP, 1996 and 1997 respectively) not only enhanced Rudd's reputation as an arranger exponentially, but have also added to Nichols' own repertoire in much the same way as albums by Rudd's old Yale cohort, Buell Neidlinger, Dutch pianist Misha Mengelberg and the music of the Herbie Nichols Project, performed by a group led by pianist Frank Kimbrough. Sadly, however, like most of Rudd's music these two albums have also passed like ships in the night, unnoticed even by some of the musical cognoscenti. During the '90s and into the early part of the new millennium Rudd also reconnected with his old friend, Steve Lacy. In what was to become one of their last recordings together, Rudd and Lacy, together with Lacy alumni/drummer John Betsch and bassist Jean-Jacques Avenel—as well as with bassist Bob Cunningham and the great drummer Denis Charles—recast some of their music together with the music of Monk and Nichols on Early and Late (2007), a double-album feature caught on tape by Cuneiform Records. This was a valuable addition to the music the two men had recorded on those other repertory records of considerable repute—Regeneration (Soul Note, 1982) and Monk's Dream (Verve, 2000)—albums that were recorded more than a decade apart.

Another all but ignored masterpiece of that period is Eventuality, the record that Rudd made with the saxophonist, Charlie Kohlhase. This album featured some of Rudd's compositions that have not often made it to album, but are wonderful studies in the career of the trombonist and composer. During the same time, Rudd also reconnected with his old employer, Archie Shepp, making Live in New York an album that brimming with the energy of both musicians in a memorable setting. Rudd revisited Nichols again when he recorded Sexmob with Dime Grind Palace (Ropeadope), in 2003. But his greatest series of recordings had only just begun during the new millennium.

Another all but ignored masterpiece of that period is Eventuality, the record that Rudd made with the saxophonist, Charlie Kohlhase. This album featured some of Rudd's compositions that have not often made it to album, but are wonderful studies in the career of the trombonist and composer. During the same time, Rudd also reconnected with his old employer, Archie Shepp, making Live in New York an album that brimming with the energy of both musicians in a memorable setting. Rudd revisited Nichols again when he recorded Sexmob with Dime Grind Palace (Ropeadope), in 2003. But his greatest series of recordings had only just begun during the new millennium. Late in the '90s, Rudd formed an enduring relationship with the enigmatic Verna Gillis and Soundscape. Gillis, who credited Rudd with being her mentor in the vast ocean of ethnomusicology, fulfilled the trombonist's enduring dream of visiting Africa on a musical adventure. MALIcool (Sunnyside, 2003)—Rudd's extraordinary collaboration with the Malian kora legend, Toumani Diabate—was the first in the Soundscape series that Rudd made under Gillis' brilliant production. This virtual tour de force recalls the mighty cultural collisions featuring Pharoah Sanders and Maleem Mahmoud Ghania, and Ornette Coleman's West African sojourns as well.

MALIcool features Rudd's superb composition, "Bamako," for the first time. The song is a soulful tribute to the city of Diabate's birth, where the two musicians met and recorded. Its singular melody is one that seduces the mind's ear and winds its way into the heart remaining there to be sung, unprompted, as if by magic. Throughout the album, the music is infused with the near-mystical interweaving of Rudd's blues and majesty of Diabate's Malian folk music. The compositional credits are shared by the two musicians and in one of the finest moments of the album, Diabate and Rudd recast a classic Monk chart, "Jackie-ing," where kora and trombone carry on a magnificent, angular exchange as chorus after chorus of Monkisms unfold with rare beauty.

Rudd began to soar ever after. The West African album was followed up with another superb one featuring the great Mongolian throat-singer, Tuvsho (Battuvshin Balansteren) and The Mongolian Buryat Band. On Blue Mongol (Sunnyside, 2005), Rudd continued his global odyssey with Verna Gillis. Here arrangements of traditional music from East of the Urals sways with rhythmic abandon alongside Rudd's compositions created especially for the set. Charts such as "Blue Mongol" share the spotlight with traditional wonders such as "The Camel," soaring with magisterial abandon as Rudd's swaggering trombone melds with the guttural melodism of Tuvsho's throat singing. The musicians also surprise even themselves with a stellar medley of classic Americana: "American Round" features a surprisingly beautiful string of melodies including "Swing Low Sweet Chariot," "Coming In On A Wing And A Prayer" and "Amazing Grace." The album concludes with an unforgettable version of Rudd's composition, "Honey On The Moon."

Rudd's next stop was Latin America. His collaboration with the Puerto-Rican cuatro player, Yomo Toro and a large ensemble, together with Bobby Sanabria and Ascension and sees the trombonist taking the plunge in too the world of merengue, son, cumbia and danzon. El Espiritu Jibaro (Soundscape, 2007) features a spirited version of Rudd's classic ballad, "Loved by Love." The chart is given a rousing gospel treatment by vocalist Alessandra Belloni. It was Rudd's uncanny way of putting a traditional form of music together with a musician of unspoken beauty—in this case vocalist Belloni—that characterized his work of this period. The musical instinct and breadth of knowledge of both Rudd and Gillis also contributed to making this album one that will remain a stellar project beloved by both the American and the Latin American musical worlds. The inimitable talents of Cuban tres player, David Oquendo, also make their first appearance in this album. Rudd later joined forces with Oquendo to make another memorable Latin music album, Encuentro (Mojito), but this album never made it to the Soundscape series, and had to wait until 2008 until it was independently released.

Rudd's next stop was Latin America. His collaboration with the Puerto-Rican cuatro player, Yomo Toro and a large ensemble, together with Bobby Sanabria and Ascension and sees the trombonist taking the plunge in too the world of merengue, son, cumbia and danzon. El Espiritu Jibaro (Soundscape, 2007) features a spirited version of Rudd's classic ballad, "Loved by Love." The chart is given a rousing gospel treatment by vocalist Alessandra Belloni. It was Rudd's uncanny way of putting a traditional form of music together with a musician of unspoken beauty—in this case vocalist Belloni—that characterized his work of this period. The musical instinct and breadth of knowledge of both Rudd and Gillis also contributed to making this album one that will remain a stellar project beloved by both the American and the Latin American musical worlds. The inimitable talents of Cuban tres player, David Oquendo, also make their first appearance in this album. Rudd later joined forces with Oquendo to make another memorable Latin music album, Encuentro (Mojito), but this album never made it to the Soundscape series, and had to wait until 2008 until it was independently released. After his Latin sojourn, Rudd returned to the musical mainland of America with one of the finest albums in the history of his repertoire. Keep Your Heart Right (Sunnyside, 2007) returned the composer to the soundscape of his bold, brassy, trombone. Rudd had discovered the exceptional musicality of pianist Lafayette Harris, Jr. and together with the unbridled ingenuity of Korean-born/American-based vocalist Sunny Kim and the melodic and rhythmic gymnastics of bassist Brad Jones, he created an album of singular beauty. The purity of Rudd's melodism on this album is perhaps its most enduring aspect. "Loved By Love" becomes a ballad of exceptional beauty again, while "Bamako" is rendered with its simple melodic lines in stark, soaring patterns that swirl around, seeming to awaken the musical universe with dewy splendor. The gospel tinge also flavors the music surging just below the surface of the melodies of "The Light Is With Me," "All Night Soul" and the quirky "Suh Blah Blah Buh Sibi." And Rudd closes the set with a beautiful tribute to his partner and soul mate, Verna Gillis, with a truly moving version of "Whatever Turns You On Baby."

Roswell Rudd's Trombone Tribe

Just as it might have seemed impossible to top the past few years of Soundscape productions, Rudd seemed to find a new metaphor, one that he released with a purely trombone album. Trombone Tribe (Sunnyside, 2009) united the musician with some of his old colleagues and some newer ones as well. Bassist Henry Grimes made a reappearance on the album, as did trombonist Steve Swell. The trombone tribe also included the stylish Ray Anderson, Sam Burtis and Eddie Bert, the fat sound of Josh Roseman, the vibrant colorist Wycliffe Gordon and ever-talented Deborah Weisz.

The album unites these musicians of considerable, shimmering talent in a rousing history of contemporary American music, which ends with soaring mysticism in the long piece, "The Place Above." Here, Rudd's trombone tribe meets the blithe spirits in the form of the Ganghe Brass Band of Benin. The spectacular spiritual, inspired by a Sunday service Rudd witnessed in Colonou and bringing together the astounding musicianship of Benin trombonist Martial Ahouandjinou and his brother/trumpeter Magliore, is a five-part suite that explodes with the same energetic fervor that also came to typify the African-American Holy Rolling churches. Once again, Rudd's sense of adventure and childlike wonder, with which he seemed to experience the universe of sound, won out. What still remains a mystery is why accolades for his stellar work with Gillis in the Soundscape series continue to be woefully small. This, however, has never worried Rudd, who fills his world with musical energy and creativity. Returning to his roots of melodism, the trombonist has reached yet another milestone in his illustrious career as an American musical institution.

Celebrating his 75th year, Rudd released yet another fine album with Gillis at his side. The Incredible Honk (Sunnyside, 2011) is a masterpiece of musicality, creativity and the inimitable energy that Roswell Rudd brings to the more than six hundred year history of the 14 feet of brass tubing called the trombone. Like his 2008 masterpiece, Keep Your Heart Right, this album takes flight on the wings of musical melody. This is gutbucket Rudd, who also seems to meld the down-and-dirty with celestial beauty. At 75, the trombonist has proved that he can swing with abandon, ache with existential pain and take flight with the sounds of joy. His marvelous collaborations with legendary fiddler Michael Doucet and Beausoliel ("C'etait Dans la Nuit"), the intimate duet with Lafayette Harris ("Waltzing With My Baby"), a traditional Korean song featuring Sunny Kim's vocal gymnastics (the stirring "Arirang") and the ethereal beauty of "Blue Flower Blue" and "Danny Boy"—both of which star the Chinese sheng player/vocalist, Wu Tong—mark The Incredible Honk as the dawn of a new era in Rudd's legendary career, that has so far spanned six decades of sheer beauty.

Celebrating his 75th year, Rudd released yet another fine album with Gillis at his side. The Incredible Honk (Sunnyside, 2011) is a masterpiece of musicality, creativity and the inimitable energy that Roswell Rudd brings to the more than six hundred year history of the 14 feet of brass tubing called the trombone. Like his 2008 masterpiece, Keep Your Heart Right, this album takes flight on the wings of musical melody. This is gutbucket Rudd, who also seems to meld the down-and-dirty with celestial beauty. At 75, the trombonist has proved that he can swing with abandon, ache with existential pain and take flight with the sounds of joy. His marvelous collaborations with legendary fiddler Michael Doucet and Beausoliel ("C'etait Dans la Nuit"), the intimate duet with Lafayette Harris ("Waltzing With My Baby"), a traditional Korean song featuring Sunny Kim's vocal gymnastics (the stirring "Arirang") and the ethereal beauty of "Blue Flower Blue" and "Danny Boy"—both of which star the Chinese sheng player/vocalist, Wu Tong—mark The Incredible Honk as the dawn of a new era in Rudd's legendary career, that has so far spanned six decades of sheer beauty. His hair is as white as mine is today. Suddenly, the sound of his trombone comes into my mind with notes spinning, as if they are myriad dancers illuminating the melody of "Danny Boy." This time it is the voice of Wu Tong that awakens the musical universe from the skies above China, Scotland and America, as Sheila Jordan once did on the unforgettable "Lullaby For Greg." Tears rush down my cheeks, each a river of pain that glistens, as Rudd plays the melody of a song my mother taught me. I realize, all over again, how I connected with the world beyond my horizon, through the art of song that Rudd seems to bring to life every time he puts his lips to the mouthpiece of his trombone.

[Author's note: With special thanks to Bret Sjerven of Sunnyside Records and Joyce at Cuneiform Records, as well as to Martin Davidson of Emanem in the UK, for filling in the gaps. Moreover the deepest gratitude goes to Verna Gillis for her patience and enthusiasm, and for opening her world of music to me. Dedicated, of course to the inimitable Roswell Hopkins Rudd, Jr.]

Photo Credits

Page 1: Cees van de Ven

Page 2: Mark Ladenson

Pages 3, 5: Dave Kaufman

Page 4: Hans Speekenbrink

Page 7: Verna Gillis

Tags

Roswell Rudd

Highly Opinionated

Raul D'Gama Rose

United States

Howard Johnson

Hod O'Brien

Beaver Harris

Sheila Jordan

Dewey Redman

Charlie Haden

archie shepp

Grachan Monchur III

JJ Johnson

Thelonious Monk

Herbie Nichols

Steve Lacy

James P. Johnson

Louis Armstrong

duke ellington

Al Hibbler

Bessie Smith

Billie Holiday

Ella Fitzgerald

Alan Lomax

Steve Turre

Charlie Parker

Cecil Taylor

Buell Neidlinger

John Tchicai

Gil Evans

Reggie Workman

Milford Graves

Albert Ayler

carla bley

Elton Dean

Steve Swell

John Bacon

Misha Mengelberg

Herbie Nichols Project

Frank Kimbrough

John Betsch

Jean-Jacques Avenel

Bob Cunningham

Dennis Charles

Charlie Kohlhase

Ornette Coleman

Alessandra Belloni

Lafayette Harris

Bradley Jones

Henry Grimes

Ray Anderson

Sam Burtis

Eddie Bert

Josh Roseman

Wycliffe Gordon

Deborah Weisz

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.