Home » Jazz Articles » Big Band in the Sky » Frank Kimbrough: From Now to Forever—A Remembrance

Frank Kimbrough: From Now to Forever—A Remembrance

Courtesy Ludovico Granvassu

The cause of death was not Covid-19, but the shock at the untimely loss of a revered artist was not any less powerful. Frank Kimbrough had the rare gift of touching lives with much more than his remarkable music.

In order to pay tribute to his legacy, we have collected remembrances, anecdotes and reflections from many of his closest collaborators, students and friends, who, at our request, have also selected music that in their heart immediately evokes memories of Frank Kimbrough [listen to this Mixtape's Part 1 and Part 2].

From time to time, Kimbrough would lock himself in a room and play the same composition for hours on end, revealing new angles and aspects at each play. Reading through these many touching tributes one has the same contrasting feelings of both consistency and surprise, as these tributes unanimously describe a man whose true work of art was life itself, while adding individual view points on Kimbrough's legacy. Music was central to this legacy, but music was just a manifestation of Frank's true nature, affable and unfazed, focused but not dogmatic, resolute in his search for beauty even when the circumstances threw him a curveball. With Frank Kimbrough, what you saw, and heard, is what you got.

Living a life like his in these times is perhaps the highest form of counter-culture. In a world that seems to have forgotten what authenticity means, you cannot fake being a Frank Kimbrough. Maybe that explains his disdain for the current state of affairs and why the jazz world—or at least that part of the jazz world where faking is not cool—gave him much needed respite.

For his fans, the sudden loss comes with the realization that even though he had been around for a few decades, musically the fun was just beginning and great albums, projects and concerts were certainly in store. For those who were closer to him, his passing took away much more, as the tributes below detail.

He left as he liked to play, without rehearsal, taking a walk from the "now" that he constantly inhabited to the "forever" which will continue to live through his recordings, life lessons imparted to his adoring students, and many stories about him that had already entered in the jazz mythology whose legendary tales he so fondly shared with students, friends and colleagues.

I can picture him up there, with his signature grin, as I'm pretty sure that the irony of this now-to-forever metamorphosis is not lost on such an "in-the-now" musician like him.

The article includes tributes, organized in alphabetical order, by: Carl Allen; Ben Allison; Jay Anderson; Matt Balitsaris; Jeff Ballard; Dave Ballou; Michael Blake; Ron Brendle; Katie Bull; Steve Cardenas; Patrick Cornelius; Jeff Cosgrove; Billy Drummond; Tim Horner; Evan Harris; Jeff Hirshfield; Ron Horton; Maitland Jones; Jimmy Katz; Landon Knoblock; Kirk Knuffke; Elan Mehler; Jimmy McBride; Jason Moran; Riley Mulherkar; Matt Munisteri; Ted Nash; Noah Preminger; Rufus Reid; Scott Robinson; Ben Rosenblum; Luca Santaniello; Maria Schneider; Kendra Shank; Mark Sherman; Satoshi Takeishi; Micah Thomas; Ryan Truesdell; Immanuel Wilkins; Matt Wilson; Steve Wilson; Christopher Ziemba; and Andy Zimmerman

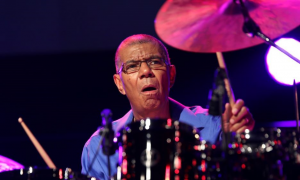

Carl Allen

I first heard Frank more than 20 years ago. He was playing at Visiones in New York City with Maria Schneider. There was something about his playing that touched me because it seemed pure. Pure as in coming from an honest place. Even though I didn't know him at the time, I felt that his playing was a reflection of his personality. Once I got a chance to meet him some years later I realized that in fact was the case.

I first heard Frank more than 20 years ago. He was playing at Visiones in New York City with Maria Schneider. There was something about his playing that touched me because it seemed pure. Pure as in coming from an honest place. Even though I didn't know him at the time, I felt that his playing was a reflection of his personality. Once I got a chance to meet him some years later I realized that in fact was the case. When I became the Artistic Director of Jazz Studies at The Juilliard School in 2008, one of the things that I wanted to do was to create an identity of our own. One that was different from what had existed since the program began in 2001 (which is when I joined the faculty).

Frank immediately came to mind, as I felt that he would bring warmth and compassion for students and the music. That was very much needed, so I hired him and this is exactly what he brought with him. His love for Herbie Nichols, Paul Motian and others added a different dimension to our offerings for the students.

Frank was a "different breed." That's something which I teased him about all the time. He didn't have a cell phone and it bothered him that people "seemed to be addicted to them" as he would say. Whenever we would send him out to Japan to do workshops and masterclasses with students from the States, everyone would comment on how caring of a person he was. He cared deeply about the students. He would often take students out for coffee or a meal to just check on them. We would often go for a meal or cigar and have the most enriching conversations about music and life. Mostly about the warmth and character of people and of jazz music.

The jazz scene will be changed forever as there is a hole in our collective soul now that Frank Kimbrough has departed. I will miss him and so will many others.

Ben Allison

It's difficult to put into words what Frank Kimbrough meant to me. When we first met in 1990, I was new to the scene and struggling to connect with other musicians. Introduced to each other by a drummer whom we each barely knew, we hit it off immediately, both socially and musically. This began a period of music-making and friendship that stretched over three decades.

It's difficult to put into words what Frank Kimbrough meant to me. When we first met in 1990, I was new to the scene and struggling to connect with other musicians. Introduced to each other by a drummer whom we each barely knew, we hit it off immediately, both socially and musically. This began a period of music-making and friendship that stretched over three decades. In the early years, we played duo gigs around town (often at a restaurant in New York City's theater district called Sophia's), where we worked out hundreds of tunes by artists such as Herbie Nichols, Thelonious Monk, Andrew Hill, Carla Bley, Annette Peacock, and Hampton Hawes. We also brought in our own tunes to try out.

At that time, I was teaching guitar lessons to children at a music school in the East Village. Frank and I regularly got together there with other musicians to work on new music. Anyone was welcome, as long as they brought in something new to play. Out of these early sessions, the idea for forming the Jazz Composers Collective, our non-profit presenting and commissioning organization that ran from 1992 to 2005, began to take shape.

When I first pitched the idea to Frank of formalizing our sessions into something more structured, his initial response was, "I'm not really a joiner." He was fiercely independent by nature—a free thinker who was not a fan of anything that even remotely smacked of "institutionalism." But as we got the Collective up and running, presenting concerts, publishing our newsletter, workshopping and premiering new works, and building a community around original music, Frank turned out to be most engaged and committed. He had zero tolerance for bullshit, but he recognized the benefits of organizing if it was done right. This is one of the things I loved about him. Once he was in, he was in. His long-running affiliations with The Maria Schneider Big Band and The Juilliard School reflect a similar, deep commitment.

Frank had a demeanor at times that might be described by someone who didn't know him as gruff. But underneath, Frank was one of the most giving musicians I've ever known. It's hard to explain to people who don't play improvised music what it means to play with a giving musician. Improvising music is very much like having a conversation. It always feels good when the person you're speaking with is listening to you and is hearing what you're saying. They can show they are doing this by acknowledging you with simple nods or feedback. It's even more meaningful when they take in what you said, consider it, and respond with a new thought that's a product of your ideas and theirs. This sets up a deeper kind of conversation, where beliefs and opinions are shaped, and minds are changed. It leads to an understanding that transcends words. This happened thousands of times over the many years that we played together—multiple moments of in depth communication. I know many musicians who enjoyed a similar experience playing with Frank.

This was true off the bandstand as well. If you were friends with Frank, you probably experienced "the hang." Hangs with Frank were some of the best and most memorable moments. The "newsletter folding sessions" with him and members of the Collective (we folded, addressed, and stamped our newsletters by hand back then) are some of my favorite memories.

The countless tours and adventures on the road. The long flights and train rides (Frank always with his New York Times crosswords). The stages, clubs, and halls (with Frank usually complaining about the piano). The food (including our regular Kimchi ramen hang). The laughter and inside jokes. The many recording sessions. When my wife and I married, Frank was our witness—it was just the three of us at City Hall that day.

As I'm thinking of all of this now, even in my profound sadness, I also feel great joy that I got to know him. I would not be the musician or person I am today without having met, shared a friendship, and created music with Frank Kimbrough. My thoughts are with his wife Maryanne, his family, his students, and the many musicians who played with him.

I loved Frank like a brother and there's a piece of my heart that's missing now. I'll carry the memories of our friendship and musical collaborations with me the rest of my life.

Jay Anderson

I have so many dear memories of Frank, it is hard to know where to start.

I have so many dear memories of Frank, it is hard to know where to start. We met playing random gigs around New York City 30 years ago. Frank was a friend, and huge fan of Paul Bley. In the early '90s, I had the good fortune to play on five recordings with Paul. Paul invited Frank to the sessions. Frank and I bonded over our mutual admiration and curiosity for Paul and his music.

I rejoined Maria Schneider's Orchestra in 2004. I had played on her first recording 10 years earlier. In the meantime Frank had become her pianist of choice. He brought so much to Maria's music. When I came back, we embarked on what would become a close personal and musical relationship. On the road we would always hang out together... Breakfast at the hotel, a long walk discovering a city, the music, the hang after the gig, the hang after the hang. So many discussions about the gig, the music we shared or discovered together, politics, passing the music on to younger people... Anything and everything. Our discussions about the music were never about the mechanics of it, but rather the history, impact and feeling of it.

I can't think of many people I enjoyed playing with anymore than Frank. Like many of the people he admired (Paul Bley, Charlie Haden, Herbie Nichols, Paul Motian, Andrew Hill, to name a few) Frank had a certain amount of musical mystery, couched in his Southern way. As a sideman, he was always prepared. But as a bandleader, he required no preparation of his side-people. When we had a gig or recording session I'd ask if there was anything I should have a look at or think about. His response was always "nah... you'll be cool." We did a live recording at the Kitano in 2012. He literally passed me the music to each tune, and then started playing. Andrew Hill, Duke Ellington, Paul Motian, Annette Peacock, Thelonious Monk, originals, Standards... anything. In two nights, we played 34 tunes and only repeated one. The set music always respected the traditions of Jazz while looking forward. Most importantly, playing and being in the moment. In the studio, there was rarely a second take.

Frank wasn't much of a practicer. It always amazed me. Bass is a very physical instrument so a certain amount of maintenance (callouses, tendons, etc.) is necessary. Frank was creative at the drop of a hat with seemingly no preparation... physically or mentally.

Frank was one of a kind personally and musically. The first one to the gig and the last one to leave. He loved being with the people of Jazz... the staff of a club, audience members, the musicians, critics that happened to be there. He treated everyone the same.

I'm honored to have shared time here with Frank Kimbrough. It's a gift I will always treasure.

Matt Balitsaris

Frank Kimbrough was what a musician should aspire to be, but very few are. He played without ego, in service of whatever the music and the situation asked of him. A number of the first records I made with him had unusual instrumentations. Ben Allison's Medicine Wheel, and Peace Pipe bands come to mind. Another pianist might have struggled to find where his space was in those unusual textures. Frank was always in the right place, right on time. Once I sketched the mixes in, I never had to change where the piano sat in those mixes. It was already where it needed to be. I think it was that trait which made him an essential component in Maria Schneider's Orchestra.

Frank Kimbrough was what a musician should aspire to be, but very few are. He played without ego, in service of whatever the music and the situation asked of him. A number of the first records I made with him had unusual instrumentations. Ben Allison's Medicine Wheel, and Peace Pipe bands come to mind. Another pianist might have struggled to find where his space was in those unusual textures. Frank was always in the right place, right on time. Once I sketched the mixes in, I never had to change where the piano sat in those mixes. It was already where it needed to be. I think it was that trait which made him an essential component in Maria Schneider's Orchestra. We are the same age, both come from the South, and both came to New York about the same time. Long before I met him, I had a gig playing guitar at a restaurant on MacDougal Street, around the corner from the Village Corner, where Frank played solo for many years. We had so much in common, it felt like we began our friendship as old friends. But then, I think a lot of people felt that way!

We made a lot of records together. Four of his trio records (two that I produced, and two that Jimmy Katz recorded and which I mixed), many of Ben Allison's, at least three of Ted Nash's, one with Noah Preminger, The Jazz Composers Collective's Herbie Nichols Project, and the epic Monk's Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk, a six-CD box set that was recorded in six days (with Frank, Scott Robinson, Rufus Reid, and Billy Drummond) and which included every known Thelonious Monk composition. I know there are others that I'm forgetting.

We also made a solo piano record, Air, which to me, most closely captures how I think of Franks' playing. I'd just had some work done on the piano (thank you, Chris Solliday!) and I wanted to record it, with the lid removed, and experiment with different mics, and get to know the "new" instrument. I asked Frank to come out, and to experiment with textures, and to play as much as possible exploring the full range of the instrument. We weren't really thinking of making a record at the time. We were just messing around. We had a great day, I learned a lot, and neither of us listened to that recording for a couple of years! When I finally opened those files again I was floored! I got Frank to listen, we agreed to do another date, to add a couple of textures and vibes that weren't on the original date. And that became the record.

It is the sound of the inside of Frank's head. Every note is in service to the composition. There is no artifice, no bullshit. Frank never played anything to show you how hard he'd been practicing, as he never practiced (no, really!). And that was who Frank was. No bullshit. Honest, complex but never overwrought. Nothing for show; filled with integrity.

Nate Chinen wrote a beautiful obituary for Frank, which included the following quote, which I include here, because it is to me the lesson that Frank lived in his music, and which every musician could benefit from: "This is something that I tell all my students: the composition is a gift from the composer, for how you're going to improvise on this tune," he explained. "It gives you information. It gives you motive. It gives you intervals. It gives you rhythms. It gives you all sorts of things to deal with. And if you just throw all that out the window with the first chorus of your solo—to just play a bunch of patterns you've figured out in a book, or something that's going to get applause—then I think you're doing a disservice to the tune and to its composer."

That's my friend Frank, right there.

Jeff Ballard

One of the first people I started playing with when I got to New York was Frank Kimbrough. Over those first few years he, Ben Allison, and I would meet once a week and play at a school where Ben was teaching. What we played was normally whatever came to mind. No real tunes per se. Just open playing. Maybe an Ornette tune or Paul Bley or an original of ours, but mostly we played whatever came to mind at the moment. The connection between us was easy and flowing.

One of the first people I started playing with when I got to New York was Frank Kimbrough. Over those first few years he, Ben Allison, and I would meet once a week and play at a school where Ben was teaching. What we played was normally whatever came to mind. No real tunes per se. Just open playing. Maybe an Ornette tune or Paul Bley or an original of ours, but mostly we played whatever came to mind at the moment. The connection between us was easy and flowing. I wasn't gigging that much. Not enough to pay rent. So I was working as a bike messenger. At lunch time deliveries were slow so every once in a while I would be able to sneak in an hour or so to go and play with Frank and Ben.

One of those days I was really re-thinking about my being in New York. I had arrived after having played a lot back home, having been able to make a living at it playing good music with very good players. I had toured with Ray Charles for three years just before getting to New York, so to be grinding it out on the city streets riding a bike delivering photos of models or legal papers up and down the rock Monday through Friday 8—5, (as cool and adventurous as it could be at times) was absolutely not what I wanted to be doing. On that day, I was really thinking about going back to California. That day I was in a very foul mood. Tired and angry about it all. Ready to switch something up. And that day I had scheduled an hour to go play with Frank and Ben.

I showed up at the school with the bike on my shoulder, a grimy face, black grit under the fingernails (new york traffic dirt) and very a pissed off mood. The guys were there already. I walked in without saying a word. They didn't say anything. I went and threw the bike in the corner, pulled out the sticks from my bag, sat down at the drums and whacked the snare drum very hard, with all of that foul mood and frustration behind it. And then Frank just started to play. And we played.

I don't know how long it was but there came a moment of realization that I knew that what I was doing here, what I was doing right then and there with these guys, was unquestionably worth all of the other crappy stuff I was going through. It was a clear and easy decision to stay and deal after that.

Frank to me embodied that sort of frame of mind. Playing for the sake of playing, for the sake of whatever playing means to each of us. Nothing complicated. It was more important than anything else. We did what we had to to be able to play.

He never compromised this attitude. Never halfway went in. He played his heart and soul for the music as he heard it each and every time.

I will miss him. I'm so thankful to have gotten to know him and share playing with him.

Thank you Frank.

Dave Ballou

The longer one lives, the more musicians one intersects with. These relationships, forged in the creative act of music making, can be quite intimate, however, it is easy to fall out of contact with as our creative lives evolve.

The longer one lives, the more musicians one intersects with. These relationships, forged in the creative act of music making, can be quite intimate, however, it is easy to fall out of contact with as our creative lives evolve. I was fortunate to be in Frank Kimbrough's orbit for a time in the late '90s. We both played and toured with Maria Schneider; I subbed for Ron Horton in the Herbie Nichols Project; and Frank is a part of my SteepleChase recording Regards. We talked about music, life and watches (he had a wonderful wrist watch!). His generosity and honesty was refreshing and constant.

As the years went by, we saw each other less, but each time we picked up as if we had only a brief interruption rather than a multi-year break. I'll always remember Frank for his patience, both musically and personally. Musically, he could really stick with the vibe and selflessly serve the unfolding of the music. Never hurried but listening, sometimes waiting. Personally, Frank knew how to listen and when he had something to say, I always learned something.

Perhaps listening is the thing I will remember the most about Frank. He knew how to listen not only to the music but to life itself.

Michael Blake

Our community will really miss Frank Kimbrough. My thoughts are with his partner Maryanne and his entire family. Those of us who knew him are grieving and those that knew him through his music are hurting. As sad as this has made us, I don't think Frank would have wanted that. I'm sure he would prefer that we play or listen to some music. For me it was the intro to a song called "Lady Red" from an old album of mine, Drift.

Our community will really miss Frank Kimbrough. My thoughts are with his partner Maryanne and his entire family. Those of us who knew him are grieving and those that knew him through his music are hurting. As sad as this has made us, I don't think Frank would have wanted that. I'm sure he would prefer that we play or listen to some music. For me it was the intro to a song called "Lady Red" from an old album of mine, Drift. Just a few weeks ago Frank emailed me about his Julliard class. He was playing Drift for his students and told me how much they dug it. I was very flattered by this. In the last years he'd just light up when talking about his students.

When I started to play with him my first thoughts were, "this is a real jazz musician." Plain and simple it was just so obvious that he was in it way deep.

I feel so fortunate that I was able to spend time with Frank. Not only on stage, in the studio and on tour but also just hanging out. Whether assembling newsletters for the Jazz Composers Collective or killing time on tour, he was always a great conversationalist and story teller. I don't know of many who liked being around musicians and talking about them as much as Frank. And it seemed he knew everyone and everyone loved him in return.

He was outspoken at times, mostly about politics. I recall he refused to cut his hair during the second Bush administration. He was repulsed by the current one so I feel some relief knowing he saw that this fool of a President was defeated last fall. Despite his contempt for repressive conservatism, I caught him recently working alongside a musician who didn't hold the same views. Frank didn't seem to care about that and left his politics at the coat check. The stage was an open space for music making. A place where all the outside bullshit didn't exist.

When we gathered to play Herbie Nichols music I'd constantly be struggling on one passage or another. Frank would be patiently waiting for the rest of us to get it together. He could just fall right back into the book, no hesitation or apparent rehearsal or extra effort required. I loved watching him deconstruct and reconstruct Nichols' complex tunes, adapting them to his method without abandoning the essence of the compositions.

Frank was on my ill-fated first tour of Europe, promoting my album Elevated. Part of the tour was in Poland. On the first Polish gig he played on a decent upright piano, but he wasn't too happy about it. The second gig was cancelled, and the promoter wanted us to drive all day to play somewhere else. I asked for a band vote. All Frank asked was, "How's the piano?." We went through hell after that, including a tragic accident on the road. The gig was cancelled (again) while we all sat in a police station waiting to be released. Frank helped me deal with the shock. He was totally cool and collected through it all. In fact he was just looking forward to the next gig. I know many musicians have heard this story first hand from him. It's become one of those 'worst road stories ever' anecdotes that Frank could tell better than anyone.

Frank brought so much to my tunes. If I wanted a piano part 'like' Ellington or Jaki Byard he would deliver it, but it always had his vibe. I loved his touch and aesthetics. He was a brilliant and deep pianist. He had abandoned acoustic electronic keyboards years ago. As he told it, after a set he walked out of a bar on Long Island and never looked back, leaving all his gear behind. Fortunately, he did play some Rhodes on Drift and occasionally on gigs he'd play that or a Wurlitzer. But he was much more interested in 'pushing air' on an acoustic instrument. And the better the piano the happier he became.

One time in Italy the piano went out of tune during the set. Frank's playing became more animated and eventually he was going at it Don Pullen-style, something you rarely saw Frank do. Bad pianos often brought the best out of him. We'd tell him so, but he'd just scoff and wave it off like an irritating bug.

Frank loved Paul Bley and one time encouraged me to go hear his trio at Birdland. This was many years ago and I was somewhat puzzled by the set. I really didn't get it at all. It was as if they hated playing music together. Afterwards Frank came up to my table and with that trademark smile and light drawl sayid, "That was the shit."

Right back at you, brother.

Ron Brendle

It's impossible to put into words the way that Frank affected my life. He is one of the most talented and dedicated musicians that I have ever known. I met him in 1975 and he has been my source of inspiration ever since. We learned a lot about jazz together and he turned me on to a world of music that I may have not have ever been aware of otherwise.

It's impossible to put into words the way that Frank affected my life. He is one of the most talented and dedicated musicians that I have ever known. I met him in 1975 and he has been my source of inspiration ever since. We learned a lot about jazz together and he turned me on to a world of music that I may have not have ever been aware of otherwise. He has been my touchstone and brother-in-music for 45 years.

He played on four of my CDs over the years while also establishing his reputation as one of New York City's most notable pianists. The list of amazing musicians that he has played with is mind boggling.

Frank and I talked by phone every month or so. Always talking about new music that we'd listened to, politics, or just about life. I could fill a book with the stories he told me about his experiences gigging in New York and around the world.

Life will not be the same without him.

Katie Bull

Many memories are flooding in... In ten years these memories will all be just as vivid as they are now...

Many memories are flooding in... In ten years these memories will all be just as vivid as they are now... No Mistakes

"Mistakes? There are no "mistakes." There's what you choose to do, with whatever happens." Frank said this once when we were laughing after a gig about how wonderful the music was when we had failed to follow one section of the charted arrangement. "It came together as it fell apart."

Music Theory

I can still see him arriving at my WaHi door in his coat with that scarf and smile. We were working on some of my charts. I asked him if I should increase my knowledge of theory to better notate all the dissonances that I wanted. My chords didn't fit into traditional notation. He just looked at me, paused and said: "better musicians crawl out from under rocks unencumbered by all that weight." That rock imagery... "You could be out there, in a desert, and crawl out from under a rock and have really fresh ideas." He said, "You're living the right way—through your ears." He said the next generation needs to "get the pods out of their ears," and "listen to life. Music is everywhere, in the sound of everything." And he pointed to the space we were sitting in and said, ..." even in this air."

Charts

During the recording sessions for my album Freak Miracle at Systems Two in Brooklyn, we were talking about charts and I said that I didn't want my charts to be over-controlling and he knew exactly what I meant. "Good. Freedom is better. Let people be themselves." We talked about how charts were more like nautical maps or road maps; they suggest geographies but the players take the trip. He said "Charts are spatial, music is space."

Grace Under Fire

We had a CD Release at Smiths Bar for the album Love Spook and when we got there we were told the jazz room had closed but we could play anyway. They had even moved the piano out. Boom. Frank recommended renting a piano from Rockets; ..."we don't have to cancel." It all went down fast. The rented piano arrived. Meanwhile I ordered the band some corned beef from the bar. I went to the bathroom to put in my contact lenses and there was a drug raid with police pounding on the bathroom door. After the raid was done (they didn't arrest anyone), I took a deep breath and rejoined the band. "You okay?" he asked with sincere concern, and I just laughed. "Yep, at least we know it couldn't get any worse, right?" Then we got up and played such a great set! So free! Fun! At the end Matt Wilson reached up and turned off the Smith's Bar sign with a drum roll! Hah! Can you see it? (The Smith's manager said they were changing up their programming and bringing in Riverdance. He apologized for the mis-communication.) Frank came to me afterwards and said: "What you just did, now that was grace under fire." And he kept saying it over and over again... "grace under fire...." So, it occurred to me right there that he was the embodiment of grace under fire. I realized he valued grace under fire. And really he embodied the integrity of grace, under any circumstance.

Fender

At a particular club they hadn't tuned the Fender. The club shall go unnamed but we love the place. He later told me he had spent the night constructing solos around these two particular notes that were flat and also sticking. I knew I heard something different that night. Hah! It's the only time I ever saw him really angry. I liked how he channeled his feelings.

Steve Cardenas

When I joined Ben Allison's new band in 2005, I was aware of Ben's previous bands and the great musicians that played in them, Frank Kimbrough being one of those great musicians.

When I joined Ben Allison's new band in 2005, I was aware of Ben's previous bands and the great musicians that played in them, Frank Kimbrough being one of those great musicians. I didn't get to know Frank until a year or so of playing with Ben. When we finally did meet, we expressed an interest in playing together someday. Thankfully Ben made that happen, and on more than one occasion, Ben's Layers of the City is among those times. I didn't have nearly as much history playing with Frank as many other musicians, but the few times we played together had a profound effect on me. He was one of the few pianists I've ever played with that made me forget I was playing with a pianist at all, but just a great musician who put the music first. On top of all of this he was such a wonderful person, straight forward with a wry sense of humor. My kind of guy.

Just a couple of years or so ago, Frank and I had the opportunity to contribute short interviews in film maker Michael Kelly's documentary of the great drummer, Paul Motian. We had each played with Paul and each had been big fans long before those playing opportunities arose. I mention this because of the drive up to Michael's place a little north of town, the hang and the drive back. That was the only chance I got to spend a significant amount of time alone with Frank outside of playing. I'll be forever grateful for that day as I now know exactly what Frank's oldest friends mean when they say he was the greatest hang. He made you feel like you'd been friends forever.

Patrick Cornelius

In every respect, Frank was genuine. He treated first year Juilliard students with the same kindness, respect, and regard as he did seasoned professionals. Like countless others, I know this from experience!

In every respect, Frank was genuine. He treated first year Juilliard students with the same kindness, respect, and regard as he did seasoned professionals. Like countless others, I know this from experience! Yes, he was a brilliant and unique pianist. Yes, he was a thoroughly invested and nurturing educator. Yes, he had a thousand hilarious stories from a lifetime in the trenches. Most of all, though, he was cool and he was kind. To everyone. He was never arrogant or pretentious (though God knows he could have been, considering his body of work.) He never coddled, never condescended, and never blew anyone off, no matter how young or inexperienced. And he was generous with his time, knowledge, and spirit.

Despite his decades in New York, I like to think that his personality retained a healthy measure of Southernity. He had a slower-paced easy-goingness to him in everyday life that reminded me that the bustle and cynicism of "The Scene" only takes you over if you let it. Getting to know him over time reminded me that I still had a piece of that in me. It showed me that making that understanding the bigger part of how I view my music and music's place in my life would make me happier, and more at peace. As I move through life, this example resonates with me more and more.

Two maxims I learned from Frank at different times go together quite well, I think. When I was a student at Juilliard, he once told me in a rehearsal, "This tune isn't about your solo, man. Your solo should be about this tune." Years later, hanging after a gig at the hotel he told me "Be careful not to make your life about music. You'll be happier if you make your music about your life." These have been guiding principles for me ever since.

I'm grateful that I got to know him. I really wish we could get to see him again once this pandemic is over. The first hang would have been so great. We'll miss you, Frank.

Jeff Cosgrove

I first met Frank in 2001 when I worked selling ads at JazzTimes magazine. I didn't know who Frank was, he was just on my list to call. He picked up the phone and we talked and talked and talked. We talked about records, especially Andrew Hill's Black Fire, which I bought that same day after our conversation, and music and jazz education. From that first conversation, I was inspired by Frank Kimbrough.

I first met Frank in 2001 when I worked selling ads at JazzTimes magazine. I didn't know who Frank was, he was just on my list to call. He picked up the phone and we talked and talked and talked. We talked about records, especially Andrew Hill's Black Fire, which I bought that same day after our conversation, and music and jazz education. From that first conversation, I was inspired by Frank Kimbrough. I started to find Frank's records which contained some of my favorite musicians and I took notice of his compositions. He wrote great tunes. Whenever I wanted to play his tunes, he sent me the lead sheets. I've performed many of his compositions over the years and had long planned to do a recording of his music. He used to joke about it in his very dark sense of humor, he would say, "do it once I'm gone, maybe then someone will want to listen to it."

Tags

Profile

Frank Kimbrough

Ludovico Granvassu

Carl Allen

Herbie Nichols

Paul Motian

Ben Allison

Thelonious Monk

Andrew Hill

carla bley

Annette Peacock

Hampton Hawes

Jay Anderson

Paul Bley

Charlie Haden

duke ellington

Anette Peacock

Matt Balitsaris

Ted Nash

Noah Preminger

Scott Robinson

Rufus Reid

Billy Drummond

Jeff Ballard

Dave Ballou

Michael Blake

Jaki Byard

Don Pullen

Ron Brendle

Katie Bull

Steve Cardenas

Patrick Cornelius

Jeff Cosgrove

John Hebert

Martin Wind

Ed Schuller

Tim Horner

Evan Harris

Jeff Hirshfield

Ron Horton

Rich Rosenzweig

Ed Howard

Paul Bollenback

Steve Williams

John Schroeder

Maryanne DeProphetis

Bill Evans

Micah Thomas

Immanuel Wilkins

Landon Knoblock

Ben Monder

Tony Moreno

Elan Mehler

Jimmy Mcbride

jason moran

Riley Mulherkar

Shirley Horn

Matt Munisteri

Sara Caswell

Ben Rosenblum

Luca Santaniello

Maria Schneider

Kendra Shank

Mark Sherman

Satoshi Takeishi

Ryan Truesdell

Matt Wilson

Steve Wilson

Christopher Ziemba

Andy Zimmerman

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.