Home » Jazz Articles » Big Band in the Sky » Frank Kimbrough: From Now to Forever—A Remembrance

Frank Kimbrough: From Now to Forever—A Remembrance

We only did one record together, Conversations with Owls, and it is a highlight for me. The way that Frank and Martin Wind created songs from thin air that were beautiful, fragile, jagged, and emotional, inspired me to such great lengths. Frank made everyone comfortable on that date. I was an inexperienced bandleader, we were playing with zero planning, and we had never played together. Frank helped pull it all together. We played a couple of nights later with Ed Schuller and Noah Preminger, both of whom took the gig on Frank's recommendation.

I found myself laughing thinking about having a conversation with Frank in 10 years. Him talking about "cats getting squirrely once the beat gets wide," or why people need to have cell phones, or his very Frank political views. He was one of a kind and I will miss him very much.

Thank you Frank. Thank you for the music, the support, your sound, and your friendship.

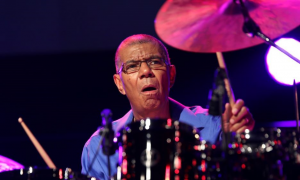

Billy Drummond

Frank Kimbrough was a colleague both as a musician and educator. My last gig in New York City at Mezzrow as a leader included Frank as the pianist and of course he played brilliantly.

Frank Kimbrough was a colleague both as a musician and educator. My last gig in New York City at Mezzrow as a leader included Frank as the pianist and of course he played brilliantly. He was musically so open and could operate in many different situations and that's one of the things that made him so enjoyable to work with.

I'm very proud to have been asked to be a part of the Thelonious Monk Project that he led. Frank made a very challenging endeavor flow like water.

As as an educator, let me just say that the students absolutely adored him and he was very passionate about sharing all of his knowledge with them. We in the Jazz Community will miss him terribly.

My condolences to his wife Maryanne and his Family.

Tim Horner

Frank became one of my long time close friends and musical partners after moving to New York City in 1980. We played sessions and gigs together, we traveled, we had record dates, we shared six years every Monday night performing at Visiones, in Greenwich Village, with Maria Schneider's Jazz Orchestra, we played in Ted Nash's many groups, The Jazz Composer's Collective... it was a large body of work together. We also knew each other in a certain way because we both grew up down South, Frankie in North Carolina (or as we would say "No Car") and me in the Southwest part of Virginia, probably three hours to where Frank was from.

Frank became one of my long time close friends and musical partners after moving to New York City in 1980. We played sessions and gigs together, we traveled, we had record dates, we shared six years every Monday night performing at Visiones, in Greenwich Village, with Maria Schneider's Jazz Orchestra, we played in Ted Nash's many groups, The Jazz Composer's Collective... it was a large body of work together. We also knew each other in a certain way because we both grew up down South, Frankie in North Carolina (or as we would say "No Car") and me in the Southwest part of Virginia, probably three hours to where Frank was from. Frank was one of the most "in the moment" musicians I have ever played with. He could and would always play the music that was flowing through him without pretension. It really hit me as we were on a tour with Maria Schneider and there were several non-playing days at the beginning of the tour. Everyone was practicing where they could except for Frank and myself as we had no piano or drums to get next to. By the time we hit our first concert, Frank didn't play as much, very reserved but the music, his playing was so intense. The next night there seemed to be more activity but it wasn't better or worse than the night before, it just sounded like Frank. The following night he built more as he was now playing three nights in a row and you could see the development, yet all three nights were so different, all great, all sounded like Frank Kimbrough.

I made note of this to him and he just said, "I'm making music with what I have, what I hear and what I own" and that he did day after day.

He lived his life that way as well.

Evan Harris

I met Frank on the day of my audition at Juilliard five years ago and was taken aback by his warmth and youthfulness. He wore his heart on his sleeve.

I met Frank on the day of my audition at Juilliard five years ago and was taken aback by his warmth and youthfulness. He wore his heart on his sleeve. That day we chatted about Sydney. He told me he loved a yum-cha restaurant near central station called the Golden Century and would often bring it up; he had some sort of life-changing dumpling there night after night. He also told me how, while on some sort of extended tour in Sydney, he ran Juilliard Jazz from an internet café next door to his hotel for a number of weeks. I didn't fully appreciate how funny this was at the time, since I hadn't learned that Frank never owned a cell phone, instead he preferred to exist "in the moment."

I was fortunate to take Frank's jazz piano class, and also studied with him one-to-one as a private student. I liken studying music with Frank to playing in a sand box—he'd set you up with the tools you needed to build your own sand castle and explore your imagination through experience and trial-and-error, with thoughtful guidance that was never dogmatic.

Frank's class took place in what will always be known to me and my classmates as "Frank's room," on the end of the fifth floor at Juilliard, looking out over Broadway and Columbus Avenue. It was an idyllic room to begin with, and an incredible spot to learn from Frank. I used to get to class early and sit and listen to Frank working his way through Scriabin or playing through something he'd been "working on," meaning he'd been "thinking about it" while walking in Central Park or walking his dogs. There'd always be a blue cup of coffee from the food truck on 65th street in hand, and his messenger bag slung over the shoulder as he walked the corridors, always ready to chat. It was bliss listening to him demonstrate some musical concept or hearing one of his countless stories about the music.

Frank was a very tranquil person, someone who had come to terms with the world and his place in it. He was always gentle and treated everyone with the utmost humility. He had many earnest words of encouragement, but none more iconic than his "yeah man." Frank taught us more than how to play piano or music, he showed us how we could live our lives and he did so in leading by example.

He always kept in touch, even after school was done for the semester, or you'd graduated, and was always willing to lend a listening ear or offer his wisdom. My classmates and I had a semi-regular meal habit with Frank. He'd come around, we'd cook dinner and he'd relive stories or tell us which track to play through the speakers, and so his lessons were never confined to the classroom. He was always vibrant, with a quick wit, an infectious chuckle and would light up the room.

Frank became family, especially over the past however many months. It meant so much to get an email checking in, always signed "Best, FK," sometimes with a recipe or a Youtube link, a book suggestion or an article. Frank deserves a medal for going from no cell phone to Zoom wizard in just a month, earlier this year.

While Frank's passing comes as a great shock, I'm grateful that Frank continued to live in the moment, as he always had, until he left us.

I love you Frank, and you will be sorely missed.

Jeff Hirshfield

Everyone's relationship with Frank was different, mine grew from our years playing together. The special thing about him was that he made everyone feel and think they were close to him, me included. It's difficult to put into words all of the memories, thoughts and feelings about my time with Frank, but like Frank would say, these are my thoughts in the moment:

Everyone's relationship with Frank was different, mine grew from our years playing together. The special thing about him was that he made everyone feel and think they were close to him, me included. It's difficult to put into words all of the memories, thoughts and feelings about my time with Frank, but like Frank would say, these are my thoughts in the moment: - The music was always spontaneous—in the moment.

- His agenda was to listen and have fun.

- Always relaxed, un-hurried.

- Always creating a mood for a vibe and a feeling to happen, it didn't matter what kind of song or style.

- Never felt contrived, never overly organized or arranged—in a good way.

- He was always cool about the music—I always felt I had his trust.

- He evoked empathy in the music and in his life as well.

- He made it so easy to be with him and the music.

- For all the sensitivity, things never felt precious.

- Passionate—organic—beauty.

- Sound—touch—blend.

- He didn't like pretentiousness and he was no bullshit about the music.

- His life reflected how he lived, his integrity, his depth and how he played and interacted with music.

- His concern and caring of people.

- Always felt like we were sharing the music, he never controlled it.

- Listening, spontaneity, integrity, mood, feel, empathy, trust, relax, passion.

- I'd ask "when's the record date?" ...he'd say, "Friday and Saturday, rehearsal is on Sunday."

Ron Horton

I first heard about Frank while I was attending Berklee in Boston around 1979. A high school friend was living in Carrboro, North Carolina, and used to see him play with his Hands Trio at a local club there called the Cat's Cradle. A little while after that, my friend at Berklee, saxophonist Scott Robinson, told me that he had played some gigs in Washington D.C. with Frank, who had just moved there from North Carolina.

I first heard about Frank while I was attending Berklee in Boston around 1979. A high school friend was living in Carrboro, North Carolina, and used to see him play with his Hands Trio at a local club there called the Cat's Cradle. A little while after that, my friend at Berklee, saxophonist Scott Robinson, told me that he had played some gigs in Washington D.C. with Frank, who had just moved there from North Carolina. I am from Bethesda, Maryland, and had decided to take a semester off from school to live with my parents. Around September of 1980 I met drummer Rich Rosenzweig, who was playing in Frank's trio, who invited me to come by their apartment and play a session. We ended up playing, hanging out and listening to records together, almost daily, for the next year until they moved to New York. During that time, bassist Ed Howard, guitarist Paul Bollenback, drummer Steve Williams and several others were all hanging out, too.

I would never have been bold enough to move to New York on my own, but when Frank and his trio moved to New York around September of 1981, I followed close behind, around three months later.

We all spent a few years scuffling, picking up gigs here and there, but always hanging out, listening to records, and playing gigs and sessions whenever we could. Around 1990, Frank told me that he had been playing some gigs and sessions with a young bassist named Ben Allison. I joined some of their sessions, learned some of their music, and around 1991, Ben's own group was taking shape. It included Frank, drummer Tim Horner, saxophonist John Schroeder and me.

Ben and Frank started planning the Jazz Composers Collective around 1992 and we began performing a few concerts a year at the Greenwich House Music School. Ted Nash was also one of the original leaders and fellow composer. Later, Michael Blake would perform with the Collective and also become one of the composers. Around 1996, we were invited to do our concerts at The New School. We performed each other's compositions and also explored music of other composers that we admired, such as Herbie Nichols, through "The Herbie Nichols Project," and Andrew Hill.

Frank was friends with Andrew Hill and was instrumental in putting me and Andrew together when Andrew, was forming a new group called the "Point of Departure Sextet." The "Collective" continued to perform, tour and record until 2011 or so.

During that time, I asked Frank to record on my CDs (Subtextures, 2002, and Everything in a Dream, 2005). Beginning around 2002, Frank and I performed and recorded with his wife Maryanne DeProphetis. We continued to do so, in various formats until just last October. In 2009, drummer Tim Horner and I co-led a tentet that included Frank.

I met Frank when I was 20, and he was a huge influence on my musical development for the next 40 years.

I will miss him terribly.

Maitland Jones

I think the first time I heard Frank live was in April of 2005, playing duets with Joe Locke at the Jazz Standard. Much of the music they played came from their earlier CD on Omnitone, Saturn's Child. There was Frank's "Waltz for Lee," Joe's "Saturn's Child" itself, and, of course, some Monk, "Trinkle Tinkle." Like most live performances of recorded work, the evening outdid the CD, with Frank and Joe playing percussively off each other. I loved it, and about a year later they reprised that evening in my JazzNights series of house concerts. At dinner afterward, talking over endless bowls of soup dumplings, I got to know them both, and that led to hearing countless gigs in New York and Frank's 10 appearances at JazzNights.

I think the first time I heard Frank live was in April of 2005, playing duets with Joe Locke at the Jazz Standard. Much of the music they played came from their earlier CD on Omnitone, Saturn's Child. There was Frank's "Waltz for Lee," Joe's "Saturn's Child" itself, and, of course, some Monk, "Trinkle Tinkle." Like most live performances of recorded work, the evening outdid the CD, with Frank and Joe playing percussively off each other. I loved it, and about a year later they reprised that evening in my JazzNights series of house concerts. At dinner afterward, talking over endless bowls of soup dumplings, I got to know them both, and that led to hearing countless gigs in New York and Frank's 10 appearances at JazzNights. It's hard to pick a single favorite of Frank's performances, but one that stands out for me is a solo evening at Smalls in April of 2010. My notes say that the piano was not in great shape, but that as the evening continued, Frank found workarounds and the sound improved. How do musicians do this? I don't know but obviously Frank did. Frank played 45 minutes straight, moving without breaks from one tune to another, with quotes from Dizzy and Monk and Bill Evans, and with songbook standards aplenty. Then he returned in a second set to do it again, 25 minutes of almost all standards this time. Finally a third set, Frank's "Quickening" I believe. It was an absolute tour de force, more than an hour of brilliance and beauty.

Another was his duo piano gig with one of his heroes, Paul Bley, at Merkin Hall in May of 2006. My notes are hard to decipher—it was dark—but I can make out more than one "stupendously brilliant!" and another "Charles Ives lives." Standards, bop tunes, and a finish with Annette Peacock's "Mr. Joy." A glorious evening by two pianists of great skill and the same mind.

Finally, may I mention October 17, 2017, again at the Jazz Standard, with Frank leading his quartet—Scott Robinson, Rufus Reid, and Billy Drummond—in a tribute to what would have been Monk's 100th birthday (OK, it was a week late). I was knocked out. The music was great, Monk-like yet fresh, respectful of history, but in the current moment. After the first set, I screwed up my courage (if not now, when?) and asked Frank whether he would consider recording all 70 of Monk's tunes. Somewhat to my surprise, his response was not, "Are you crazy?" but, something like, "Well, let's think about it." Well, he did and about six months later the group reconvened at Matt Balitsaris' Maggie's Farm studio and produced the spectacular six-CD box set, Monk's Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk (Sunnyside Records).

None of these thoughts speaks to his humanity or of his humor, or of his intolerance of nonsense and worse. I remember the day he cut his hair, having refused to do so as long as George Bush was in office. It is a pity he can't be here to see the next Great Exit from Washington. Nor does it adequately credit his devotion to teaching and to his students at Julliard.

Frank was a true American original, a genius pianist, a lovely gentleman, and a dear friend. I miss him intensely.

Jimmy Katz

Frank was a great person and a great artist. After Frank's gigs at the Kitano Hotel I would often just hang out with him for three hours on the sidewalk before we would head home. We often discussed the state of jazz and the young musicians that we both had heard. He was always polite but also said that most of them were just starting their journey as musicians.

Frank was a great person and a great artist. After Frank's gigs at the Kitano Hotel I would often just hang out with him for three hours on the sidewalk before we would head home. We often discussed the state of jazz and the young musicians that we both had heard. He was always polite but also said that most of them were just starting their journey as musicians. One night he was really excited and told me that he had two students at Juilliard that were just incredible. I was surprised at his amount of enthusiasm and I said, "Really they are that good?" He said yes, sometimes when they come for their lessons I just listen to them play because they are so original. "You have to check them out!" he said.

Of course, Frank was talking about Micah Thomas and Immanuel Wilkins. He adored them and said they were poised to do great things.

Kirk Knuffke

Frank was the coolest. Everyone thought so. I felt cooler when I got to play with him or hang out with him. A guy you would want in your corner if you ever had any trouble.

Frank was the coolest. Everyone thought so. I felt cooler when I got to play with him or hang out with him. A guy you would want in your corner if you ever had any trouble. I first met Frank on the street in Rotterdam in 2006. It would be a few years before we played together after that meeting but he immediately left a big impression on me. Matt Wilson and Kim Taylor had the idea to put Frank and I together in a duo and we had a wonderful time. After that meeting we did other duo concerts as well as trios and quartets, at the Kitano and other venues. We made a yet to be released trio recording with Masa Kamaguchi as well.

We never had a rehearsal. Frank wanted the playing to begin when the gig started, and you could always trust him, as he always made you sound better. Everything was always fresh.

I also got to play with Frank in Ben Allison's group. I remember one solo he played at Smoke with Ben's band that basically stopped everyone else in their tracks, you almost couldn't play after it!

There are many broken hearts about Frank because of the person he was, and he was a musician's musician, you wanted to hear him and be around him. When we didn't have a gig I would bug him to have lunch just to hang out.

I also love listening to his records. The Monk's Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk box set belongs in every collection for pure enjoyment as well as study. His solo album Air and Trio release Live at Kitano are always getting played in my home.

Here's one of the life lessons I learned from Frank. I arrived to play duo with him and saw the piano on my way in. Let's just say it looked pretty funky. Frank was already there, (Maria Schneider said he was always the first to arrive, another lesson). He was relaxed and cool. I hurried to get set up and I asked a little nervously "did you check out that piano?" He paused, had a sip of coffee and leaned in saying quietly, "I wouldn't dare. If something is wrong with the piano what are we going to do about it now? Just play."

And play he did. Frank had a Sound!

Landon Knoblock

Frank was first my teacher, and then my friend and mentor. I met him over 20 years ago, when I was 18 and about as green as anyone could be. I have all these fleeting memories of Frank that jumble together, like grabbing a slice at Joe's on 6th, or randomly hanging out in front of Smalls. I remember the first time he put a hand-written Andrew Hill chart in front of me ("Ball Square"), and when he played me Keith Jarrett's "Survivor Suite." I remember seeing him play with Noumena, a band with Scott Robinson, Ben Monder, and Tony Moreno, at a newly-opened Jazz Standard. I remember sitting in his apartment in the mid-aughts, looking out the window at a distant view of lower Manhattan as Frank described what it was like watching the towers fall from that very spot. The protest ponytail, the political rants, the cell phone hold out, the sound of his voice, I remember all these things. And I remember the music.

Frank was first my teacher, and then my friend and mentor. I met him over 20 years ago, when I was 18 and about as green as anyone could be. I have all these fleeting memories of Frank that jumble together, like grabbing a slice at Joe's on 6th, or randomly hanging out in front of Smalls. I remember the first time he put a hand-written Andrew Hill chart in front of me ("Ball Square"), and when he played me Keith Jarrett's "Survivor Suite." I remember seeing him play with Noumena, a band with Scott Robinson, Ben Monder, and Tony Moreno, at a newly-opened Jazz Standard. I remember sitting in his apartment in the mid-aughts, looking out the window at a distant view of lower Manhattan as Frank described what it was like watching the towers fall from that very spot. The protest ponytail, the political rants, the cell phone hold out, the sound of his voice, I remember all these things. And I remember the music. I read on Matt Wilson's Instagram that Frank "felt his legacy would be the opening of the spirits and the sounds of young musicians." This is absolutely Frank's legacy. He was the first person to truly show me what it meant to have a life in music. To be organic, to have a voice, to listen. Even as Frank showed me the contrarianism of Paul Bley, he was full of encouragement and support.

I once asked Frank if he had any advice on how to sustain a musical career in New York City. He said all I had to do was refuse to go away. Thank you, Frank. I will carry everything I've learned from you, and your memory, with me for the rest of my life.

My deepest sympathies to Maryanne and all of Frank's family.

Elan Mehler

I met Frank Kimbrough at NYU, where I attended the Jazz Program from 1997 to 2001. When you walked with Frank Kimbrough through the halls you walked slow, I swear he had a different handshake for everyone that he came across.

I met Frank Kimbrough at NYU, where I attended the Jazz Program from 1997 to 2001. When you walked with Frank Kimbrough through the halls you walked slow, I swear he had a different handshake for everyone that he came across. Frank was the prankster king of the NYU jazz scene. There were guys there that you could learn a lot from but Frank was the guy you wanted to be. Frank's been in New York for decades but he held on to his Carolina tempo and he let you know it. He didn't hustle with the flow, everything else flowed around him. His playing was like that too. I'm not saying he was one of those old-school be-boppers who hold down the time and dictates the swing; just that he was not going to struggle against the tide; he was going to ride it, and—somehow—it would always take him where he wanted to go.

Despite the certainty that you had when you were hanging out with Frank that he was cooler than you, you would never meet someone with a bigger heart. Which of course is the key to the whole thing. In an environment that's trying to nurture creativity in the context of competition, the coolest thing you can do is be genuine in your own love of the music and the musicians. Sounds easy enough, but Frank might be the only person I met, in an environment that was too often toxic, who could pull that off.

Jimmy McBride

I have a vivid memory of the first time I met Frank, which was before I moved to New York. I was still in high school and was lucky enough to get to perform at the Monterey Jazz Fest in September 2008, as part of a conglomerate big band called the Next Generation Jazz Orchestra. Frank was also playing at the festival that year with Maria Schneider. A bunch of us went to hear their set and afterwards, we went backstage in hopes of meeting some of the musicians. Maria's band was one that I had listened to and admired growing up and so I was a bit nervous to talk to any of the band members. But Frank immediately came up to a group of us and introduced himself. At the time, he was wearing his hair in a long ponytail that almost reached his butt. Someone in our group asked him about his hairdo and he told us, straight up, he hadn't cut his hair since Bush was elected and he wouldn't cut it until he was out of office! I thought that was amazing and as I got to know him after I moved to New York, I realized that interaction with him was so emblematic of his personality—warm, funny, generous with his time, and non-judgmental. He was willing to take time to talk music and laugh with some high school kids he'd never met, just because we were passionate about the music. I immediately felt comfortable in his presence.

I have a vivid memory of the first time I met Frank, which was before I moved to New York. I was still in high school and was lucky enough to get to perform at the Monterey Jazz Fest in September 2008, as part of a conglomerate big band called the Next Generation Jazz Orchestra. Frank was also playing at the festival that year with Maria Schneider. A bunch of us went to hear their set and afterwards, we went backstage in hopes of meeting some of the musicians. Maria's band was one that I had listened to and admired growing up and so I was a bit nervous to talk to any of the band members. But Frank immediately came up to a group of us and introduced himself. At the time, he was wearing his hair in a long ponytail that almost reached his butt. Someone in our group asked him about his hairdo and he told us, straight up, he hadn't cut his hair since Bush was elected and he wouldn't cut it until he was out of office! I thought that was amazing and as I got to know him after I moved to New York, I realized that interaction with him was so emblematic of his personality—warm, funny, generous with his time, and non-judgmental. He was willing to take time to talk music and laugh with some high school kids he'd never met, just because we were passionate about the music. I immediately felt comfortable in his presence. During my time in school, there was ample opportunity to hang with Frank outside the classroom. He'd often be hanging out on the street smoking a cigarette and we would joke that running into him was like entering a time warp, because you'd end up shooting the shit with him a lot longer than you anticipated. But it was great, you could always count on his humor, his unique takes on life and music, his sharing of knowledge and one-of-a-kind stories, and his willingness to listen to you too. I think that's why every student who crossed paths with him loved him—he totally did away with the sometimes-uncomfortable gap between teacher and student that could make students or young people feel small or insignificant. He made me realize that at whatever point in life or level of experience one was at, we were all striving to achieve the same mastery of our craft and that our love for music and life didn't diminish with increased age, fame, or status.

I always think that one's character comes through in their music whether they try and hide it or not. And all these great qualities about Frank that I described came through when he sat at the piano. He was real, vulnerable, unpolished in the best way, and open to making music with and listening to anybody. I was able to share the bandstand with him a few times after graduating and I always felt that same comfort and ease with him that I had the first night I met him.

I thought he would be around forever, kept going by his love for music and sharing that love with others. I will miss him dearly.

Jason Moran

Frank was a most heartfelt pianist, always tender, always searching. I'm not sure of when we first met, but upon arriving in New York he sought out Andrew Hill. Our mutual love for all things Andrew and Herbie Nichols kept us close.

Frank was a most heartfelt pianist, always tender, always searching. I'm not sure of when we first met, but upon arriving in New York he sought out Andrew Hill. Our mutual love for all things Andrew and Herbie Nichols kept us close. I was always thrilled to see or hear him on records. He found an organically soulful approach to the piano and wove the history with loose thread. He was a fixture in the scene, always finding the home in it all.

We were trading messages recently as he was laying praise on two of his Juilliard Jazz alums, Immanuel Wilkins and Micah Thomas. He listened to Immanuel's debut recording which I produced and was giving the grads the glory.

Frank taught a generation of musicians that are now here tilling the field. His work on and off the piano will be felt for decades to come.

I'll miss his sly way of talking shit and am thankful for the hugs and life talk with him, a true citizen of the music.

Riley Mulherkar

Frank was a champion of all of us coming through the jazz program at Juilliard, and in so many ways was the antithesis of the traditional conservatory way of thinking. At a time when I was spending all of my time in the practice room, he turned me on to one of his tried and true practice methods—heading to Central Park, finding a bench, and sitting by himself to read scores or let ideas marinate.

Frank was a champion of all of us coming through the jazz program at Juilliard, and in so many ways was the antithesis of the traditional conservatory way of thinking. At a time when I was spending all of my time in the practice room, he turned me on to one of his tried and true practice methods—heading to Central Park, finding a bench, and sitting by himself to read scores or let ideas marinate. In classes, he opened our ears to folks like Andrew Hill, Shirley Horn, Paul Bley, and Paul Motian, whom he brought into school one day for a masterclass. And when end-of-the-year juries came around, I remember walking into the room trembling with nerves, only to look at him amongst the panel of faculty and see that he believed in me more than any grade could express on a piece of paper.

There are many times I had with Frank that will stay with me, but one time I keep thinking about isn't a moment in a classroom or on the bandstand, but a long walk we once took through the Village. As always, he was fully present—no cell phone, no distractions, totally in the moment, just like how he made music. We walked for hours, on streets I thought I knew well until Frank shared with me the history of them... which jazz club used to be where, who used to play in what club, where the hangs until sunrise were... down to the detail of what the set times were, where the band would set up in the room, and which clubs had good pianos. That kind of generous love for the music, for his mentors before him, and for his students after him, was unmatched.

He was one of a kind.

Ted Nash

The passing of Frank Kimbrough has changed me. I am not the same. There is a piece of me that is now missing, and I feel it every day.

The passing of Frank Kimbrough has changed me. I am not the same. There is a piece of me that is now missing, and I feel it every day. I first met Frank when I pulled up in front of his Long Island City apartment building and he climbed into my Honda Accord for a thirteen hour ride to Cincinnati to begin a two-week tour with my quartet. When we finished the gig at the Blue Wisp that night, I knew I had found a musical soulmate.

Over the following more than thirty years we have been collaborators on dozens of concerts presented by the Jazz Composers Collective. We have made music together on many recordings, including albums by Ben Allison, The Herbie Nichols Project as well as several of my own releases.

Frank was extremely intelligent and sensitive. He could get dark at times, which is understandable given the state of the music industry, especially for someone who wasn't looking for commercial success but instead searched for truth and honesty in his music and in his relationships. He was very opinionated and politically aware. He refused to cut his hair for four years in protest of a particular occupant of the White House. At the end for those four years, when the administration changed hands, Frank watched the outgoing POTUS board Marine One and take off from the White House, and then went to get a hair cut.

About five years ago Frank and I were hanging out at the bar at the Jazz Standard, listening to a group of six young musicians, mostly in their twenties, and I noticed that three of the musicians were sporting cute hats. I turned to Frank and whispered "what's up with the hats?' He took a moment without looking at me, and then responded "ya gotta earn the hat!"

I noticed something during the past ten years: that Frank's tendency towards darkness lessened. Frank joined the faculty at Juilliard a dozen years ago, and through his teaching and mentorship I really believe he found deeper meaning and purpose. Since Frank's passing I have heard countless students describe how Frank made them feel they were special and important. After classes or lessens Frank would walk with them for hours in the streets at his unhurried, North Carolina pace, talking music and many other things.

One thing is clear: Frank earned his hat and much more. While maybe not a household name, those who knew his music all agreed that he was one of most important pianists and composers of our generation. He has taught and inspired more people than he probably realized. I know I am a better musician and a better person because of Frank Kimbrough.

Matt Munisteri

I only worked with Frank a handful of times, but I was so saddened to hear of Frank Kimbrough's passing. Frank showed me a kindness that was clearly second nature to him, but in my experience is actually pretty rare among jazz musicians.

I only worked with Frank a handful of times, but I was so saddened to hear of Frank Kimbrough's passing. Frank showed me a kindness that was clearly second nature to him, but in my experience is actually pretty rare among jazz musicians. The few times we played together were in concert and club situations where we were presenting new music, and I was playing many more written parts than I'd ever had to. I assumed for years that other musicians understood what I meant when I told them I didn't read, so it took me a very long time to grasp that the message wasn't getting through. They really had no idea what I was talking about. For the record, I'm a little better now, and I can certainly write much more fluidly than I can read (though, still the next day I sometimes can't de-code what I wrote), and the notes no longer appear to be going down while the pitch is going up, and vice versa (well, not always), but things were not always thus...

When you learn to play on your own, as a child, maybe after a friend shows you a little something to get you going, and then for 20 years you have music pouring out of you, while you're simultaneously busy constructing a framework for music in your head—your own web of meaning through which you can process your ideas —I think the neurons must just get aligned differently. That ink all over the page has absolutely no resemblance to the matrix you've built in your head. But then suddenly people are putting pieces of paper in front of you and expecting you to at least *make some sense* of it—even after you've diligently tried to make them understand that you can't, and in plenty of instances even asked them to call someone else—and at that point, physical symptoms start to present. I'd break out in a sweat, get fall-outta-my-chair dizzy, nauseas, start to float outside and above myself, and even experience actual bouts of a kind of blindness—seeing either the tiniest bit of light in a swirling black fog, or shards of jagged light which no image could penetrate. So, desperate now, you go and call on your brain—that part of you that you flogged so mercilessly in every other part of life, but left under a palm tree to enjoy a mai tai when you got to split and make music—to come to the rescue. And your brain says "uh...not me Jim! I didn't sign up for this shit!" and checks out, goodbye.

It's usually at this point that you wake up to the roaring in your ears and become aware that the room has become silent and 8-10 much better musicians are staring and wondering how the fuck they got roped into a session with the guy who's right now sitting in your chair.

You dig?

Anyway... even the first time we ever played one of these things—over 20 years ago?—Kimbrough quickly picked up on what was going on before it ever had a chance to really get going, and he kept it up, being very attuned to everything that was happening on the bandstand, in rehearsals and then during the concerts. He knew when I might start struggling, and he'd VERY quickly, and VERY quietly, toss off just enough of my next cue on the piano so that my musical memory could kick in. He never looked at me, he never asked me if I needed help, and I never saw him give a "knowing glance" to anyone else in the band. If the bandleader ever instructed him to perform this service, I certainly missed it (and generally, in my experience, bandleaders make sure you don't miss those instructions). My memories now of these shows are mostly of the moments of immense relief that he provided, and of my then glancing sideways at him in the hopes of conveying just a small expression of gratitude, only to catch a quick glimpse of him with his head slightly cocked, his eyes fixed on a far corner of the ceiling hovering out over the audience.

I'm grateful to be reminded now of the power of this kindness. My sincerest condolences go out to his family and to my many friends who knew him much better than I did and who are now experiencing a terrible emptiness.

Noah Preminger

I met Frank Kimbrough when I was 20 and we immediately jived together. It's easy when you have similar taste in musical style and appreciation for originality, mutual hatred for the political system, and so on.

I met Frank Kimbrough when I was 20 and we immediately jived together. It's easy when you have similar taste in musical style and appreciation for originality, mutual hatred for the political system, and so on.

Tags

Profile

Frank Kimbrough

Ludovico Granvassu

Carl Allen

Herbie Nichols

Paul Motian

Ben Allison

Thelonious Monk

Andrew Hill

carla bley

Annette Peacock

Hampton Hawes

Jay Anderson

Paul Bley

Charlie Haden

duke ellington

Anette Peacock

Matt Balitsaris

Ted Nash

Noah Preminger

Scott Robinson

Rufus Reid

Billy Drummond

Jeff Ballard

Dave Ballou

Michael Blake

Jaki Byard

Don Pullen

Ron Brendle

Katie Bull

Steve Cardenas

Patrick Cornelius

Jeff Cosgrove

John Hebert

Martin Wind

Ed Schuller

Tim Horner

Evan Harris

Jeff Hirshfield

Ron Horton

Rich Rosenzweig

Ed Howard

Paul Bollenback

Steve Williams

John Schroeder

Maryanne DeProphetis

Bill Evans

Micah Thomas

Immanuel Wilkins

Landon Knoblock

Ben Monder

Tony Moreno

Elan Mehler

Jimmy Mcbride

jason moran

Riley Mulherkar

Shirley Horn

Matt Munisteri

Sara Caswell

Ben Rosenblum

Luca Santaniello

Maria Schneider

Kendra Shank

Mark Sherman

Satoshi Takeishi

Ryan Truesdell

Matt Wilson

Steve Wilson

Christopher Ziemba

Andy Zimmerman

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.