Home » Jazz Articles » Big Band in the Sky » Frank Kimbrough: From Now to Forever—A Remembrance

Frank Kimbrough: From Now to Forever—A Remembrance

This guy had a beard down to his belly button, straight off the Viking ship sort of a vibe. He walks up to the microphone and just rips the loudest low Bb honk you have ever heard, shaking the entire room. For the entire solo! Frank and I looked at each other and laughed harder than a person ever thought they could laugh. I mean, for the remainder of the concert we were crying in laughter. It was such a silly moment, but we had a good amount of those and I truly loved spending every moment with Kimbrough on and off the bandstand.

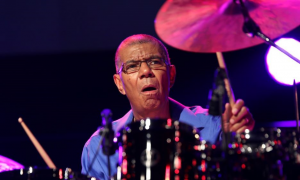

Rufus Reid

I am still in shock of the knowledge that my friend and musical colleague, Frank Kimbrough, is no longer with us. I knew and admired Frank's musical abilities as a member of the Maria Schneider Orchestra long before we actually met. There was always something in his playing, whether he was soloing or comping, that engaged me.

I am still in shock of the knowledge that my friend and musical colleague, Frank Kimbrough, is no longer with us. I knew and admired Frank's musical abilities as a member of the Maria Schneider Orchestra long before we actually met. There was always something in his playing, whether he was soloing or comping, that engaged me. When we actually met, it was like we had known each other a very long time. Frank's musical scope was huge. He could play anywhere the music was going. He loved Herbie Nichols, Thelonious Monk, and Andrew Hill, to name just a few. He always commented on the albums I recorded with Andrew Hill. I think that was a link that began to bond our friendship. We were always talking about a particular record or a tune that intrigued us. There were a few years of just hanging out before we actually played together.

I got the opportunity to perform with a trio for Vespers at a church in New Jersey. I called Frank to ask if he would do it with me and he said, yes. I also asked violinist, Sara Caswell, who also had not played with Frank. I sent each my music ahead of time. The afternoon was special and confirmed that Frank, Sara, and I connected beautifully. That was the beginning!

I recorded two albums on Newvelle Records because of Frank, who was the first to record on that label. He called me to play one night at the Jazz Standard celebrating Thelonious Monk. Little did we know that was the birth of the quartet with Scott Robinson, Billy Drummond, me, and Frank eventually recording all of Monk's music. I was always astounded how Frank and Scott rendered these unique melodies as if they were one! The four of us became closer from this particular project, which I am deeply proud.

Frank Kimbrough kept the bar "high" no matter what music he was playing. Frank Kimbrough's personality was low-key, but incredibly focused. For me, Frank was a musical journeyman that was always there consistently keeping it all moving. He should have been more widely known for his music and piano playing, but he didn't concern himself about any of that stuff. But the players he played with in New York City, knew how "heavy" he was and already miss him, big time!

I feel blessed to have wonderful memories making music with the special individual, Frank Kimbrough. May he rest in peace!

Scott Robinson

It seems that 2020 has checked its watch, and realized it better hurry up and get its last licks in. So far, this heartbreaking year has taken about a dozen of my colleagues by means of the COVID virus, and about as many more by various other causes. That's a couple dozen people I've played music with, and never will again. Other friends have survived COVID, but with lasting damage. Another dear friend has been put in a mental hospital. And now, in the waning hours of the year, comes one more, particularly devastating loss: Frank Kimbrough, one of my oldest friends in this art form.

It seems that 2020 has checked its watch, and realized it better hurry up and get its last licks in. So far, this heartbreaking year has taken about a dozen of my colleagues by means of the COVID virus, and about as many more by various other causes. That's a couple dozen people I've played music with, and never will again. Other friends have survived COVID, but with lasting damage. Another dear friend has been put in a mental hospital. And now, in the waning hours of the year, comes one more, particularly devastating loss: Frank Kimbrough, one of my oldest friends in this art form. When I got the unbearably shocking news of his death yesterday, I just sat on the couch and cried. Then I hid under a blanket. After a couple of hours of this, I tried to watch an old movie. Finally, unable to avoid it any longer, I went out to my Lab, at around 4 AM, and recorded a solo tenor improvisation for Frank. When I can bear to listen to it, I'll put it out there somehow.

I knew Frank before there was a Maria Schneider Orchestra. Before either of us moved to New York. Ron Horton just reminded me that I told him about Frank, and suggested they get in touch, back when Ron and I lived in Boston (years later the two of them became co-founders of the Jazz Composers Collective). So Frank and I go way back. Neither of us could remember exactly how we met—probably at some Washington, D.C. jam session—but it was some time in 1979 or 1980. He always spoke fondly of our first gigs, at the Boar's Head Inn somewhere in Virginia, where I would show up in my 1949 Plymouth loaded with instruments.

After we both ended up in New York, he landed a steady piano gig at The Village Corner on Bleecker Street ("At the Corner of Walk and Don't Walk"), where he held forth for years, playing solo for an assortment of drunks, characters, and—sometimes—music fans. I used to pop in there and see him, and we would chat. He had an edge in those days, an irritable side, that noticeably mellowed out when he married his wonderful Maryanne. He seemed a much happier person after that, more relaxed about life, although he kept his BS-meter finely tuned and always at the ready.

I can't recall if I had a hand in bringing Frank to Maria Schneider's attention or not, but he became a tirelessly loyal collaborator for some 30 years—as indispensable to her music as Hodges was to Duke. I have so many pictures in my mind of the two of them hunched over the piano, figuring out how to stop the strings and where, and with what materials, to get the many otherworldly effects heard in the Winter Morning Walks project with Dawn Upshaw.

Frank did everything his own way. He never owned a cell phone. He never practiced, believing in "saving it for the gig." Frank's political views were decidedly liberal, and some of the ways he expressed those views were legendary. Few of us in the band will forget his refusal to cut his hair for the entirety of G.W. Bush's eight-year tenure in the White House. But his outrage at its current occupant was beyond even the ability of such an act to express. I regret that Frank did not live to see "that fool," as he often called him, thrown out of there.

When I built my studio, ScienSonic Laboratories, Frank was one of the first people I invited to come out and record an album of improvised duets. Normally very fussy about pianos, Frank readily agreed even though I only had a medium-size piano ("Hey, it's still a Steinway")... and he even consented to play some electronic instruments like Hammond and Farfisa organs, something he normally would not even consider (I recall him leaving a rehearsal once when the only available instrument was an organ of some kind). So in August of 2010 we spent a day in the Lab and recorded our album Afar, which is something very different than anything else we had done together. Most of our live duo performances consisted of tunes, and we had developed a way of moving in and out of tunes which involved a very special kind of communication which I can honestly say only happens with a very few people. That's part of what hurts so much: I've not only lost a friend, but I've lost that music—the music that only happens when I play with that person. Unfortunately, those very special tune-based duet evenings were never really documented, although we had talked of recording one.

When Frank tapped me to record, with Rufus Reid and Billy Drummond, a mammoth six-CD set of all known Thelonious Monk compositions, I was stunned. What an incredible opportunity to learn, grow, and play great music with great people. We had an amazing six days of music and camaraderie out at the recording studio "Maggie's Farm" in rural Pennsylvania and managed to get good takes of all 70 tunes. The hang and the vibe were as good as the music. I will always be grateful for that experience. One of my favorite tracks from the project, though, is one of the few I don't play on: "Functional," a little unaccompanied blues piano gem. I was moved to write to Frank about it: "I don't know too many cats who can play like that. Has that hint of stride feeling, but very relaxed... completely unhurried, creative and beautiful. I honestly don't know too many pianists who could pull something like that off."

There are so many regrets when someone like this leaves. The unsaid words. The unfinished projects... the ones discussed but not yet begun. The missed opportunities that now will never come again. One of those that will haunt me for a very long time came when the Monk group was scheduled to perform a livestream from Smalls—as my own quartet had done a couple months before, in an empty club, for Monk's birthday in October. Three weeks before the gig, we were told there would now be an audience of 20... and I got nervous. Much as I desperately wanted to play, I asked the others if this was really a good idea. Rufus seconded my concerns, and nobody wanted to do the gig if I wasn't comfortable about it. Frank took a raincheck from Smalls, telling me, "Don't give it a second thought. We can do it at another time, a better time... a safer time." Then we were offered another date in late November, again with the audience, and the COVID situation wasn't any better. This time I was really in agony over it, and suggested that maybe they should just do the gig with another horn player. Frank wouldn't hear of it. "We can't do it without you," he said. "I can't imagine you not being there." So those gigs didn't happen, and despite his optimism, now they never will... and I must live with the fact that my fears of COVID took away my last two chances to ever play music with Frank Kimbrough, and with that wonderful group.

Now, as I look out the window and watch the sun finally set on this year of heartbreak and death, I find it is my unhappy turn to say, after 40 years of friendship and music, "Frank... I can't imagine you not being there."

Ben Rosenblum

One of my dearest friends and mentors passed away, the legendary pianist Frank Kimbrough. It's hard for me to describe adequately what a loss it is, and what an empty space I feel thinking that I won't ever hear him perform again, or hear his stories again... all of his incredible anecdotes about the people who mentored him and the experiences he had on the road, many of which I heard multiple times but always enjoyed just as much every time. I think everyone who spent any time at Juilliard was moved and shaped by Frank.

One of my dearest friends and mentors passed away, the legendary pianist Frank Kimbrough. It's hard for me to describe adequately what a loss it is, and what an empty space I feel thinking that I won't ever hear him perform again, or hear his stories again... all of his incredible anecdotes about the people who mentored him and the experiences he had on the road, many of which I heard multiple times but always enjoyed just as much every time. I think everyone who spent any time at Juilliard was moved and shaped by Frank. So many anecdotes come to mind. The first is his advice on practicing. He said to many of us students that he didn't practice, he played. "Playing was his practice." This advice was delivered to me in a particularly memorable way when, a couple years after graduating Juilliard, I went to one of his shows and mentioned to him that I was feeling like I didn't have time to practice as much as I wanted to. To which he replied emphatically, "man, you don't need to practice!," as if I had suggested the most insane thing imaginable. I think he felt that too many people were not practicing in the same way they were going to play on a gig. So in that sense, they weren't spending time actually working on the skill that they were going to need when performing. Any time Frank played, he played as if performing, with his whole being, so honestly and beautifully. When he suggested in our lessons that I spend hours at a time with a single ballad, it was to get to know that ballad intimately in the way that one gets to know a song when one has performed it hundreds of times, and explore every corner and bend in it thoroughly, from the inside out.

He would spend hours at a record store looking through albums and buying them on a whim just to see what they were about. He told me about the recordings that he held dear, and also the ones he destroyed. Somewhere I have a notebook full of recommendations that he made to me over the years.

Frank had so many stories that he loved to tell, both about his experiences on the road and about his mentors, specifically Andrew Hill, Shirley Horn and Paul Bley. He loved Paul Bley stories in particular because of Paul Bley's bravado and arrogance, which was always delightfully juxtaposed to Frank's humble but confident demeanor. So I remember stories about Paul Bley telling a jazz club usher who didn't recognize him, "Oh, I don't pay covers. I'm Paul Bley, pianist extraordinaire." Or the story about Paul telling Frank that he heard him on Marian McPartland's show, and then asking Frank why he played with her, rather than playing against her.

Frank also told a story about Paul Bleys's wife playing to him a recording of Paul Bley with Paul Motian and some other musicians that had passed before him, and telling him that those musicians were waiting for him. When the record ended, the door swung open suddenly, startling Paul's wife, and when Paul's wife looked back, Paul had passed. Frank interpreted it like Paul's soul rushed out of his body, because it was time to be reunited with the musicians he so loved to play with.

The other thing to mention about Frank is that he was "always there." He was the only teacher I've had that consistently would come to my performances. I know he was one of the only teachers at Juilliard that was at almost every student's senior recital. After a concert I played shortly after graduating, Frank told me he intentionally came in a few minutes after start time so that I wouldn't notice that he was there. He didn't want me to play any differently because he was watching. He wanted to see me play honestly and the way I wanted to play. I think this taught me a lot, not only about how I should play, but also that Frank understood the impetus to want to play differently for people listening.

I learned so much from his music. Every time I saw him I gained some new insight into what I needed to work on, and what was truly important. His musical voice shined through so honestly and clearly. He played in a way that got right to the heart of the matter. No extra notes, no pretense, nothing that distracted from the pure and raw emotion of the musical statement he was making. The music mattered so much to him.

I always think of Frank as one of the most self-assured pianists. He would play exactly his signature style of piano in every circumstance, so the thought that he understood what it was like not to have that mindset really has given me hope that one day, I can be as self-assured and confident in what my voice is as he was. I try to improve in this regard every time I sit down at the piano.

Luca Santaniello

I met Frank my first semester at Juilliard as a student. I knew of him before, through his association with Maria Schneider and as a band leader, but i did not really associate his name with any face.

I met Frank my first semester at Juilliard as a student. I knew of him before, through his association with Maria Schneider and as a band leader, but i did not really associate his name with any face. The first impact was nice, gentle and welcoming. He was very interested in who I was, where I came from and various aspects of my Italian culture such as food, clothes, a romantic approach to life and, of course, my musical background.

Coming from a small provincial city himself, he was immediatley interested in finding a common ground with me, a young jazz player from an equally small provincial town in the south of Italy, Campobasso.

I would always meet him in his office at Juilliard hanging out, talking to some students about music, life, giving advice on how to move forward while facing the problems and challenges that young jazz musicians in New York may face in their academic life. Or I would find his complicit look when we had a break between Juilliard Jazz auditions to go and have a smoke outside and talk some shit! He had no filters when it came to dealing with BS, very straight up on giving you his opinion about things that weren't right or appeared bluntly unjust.

If, on the one hand, he was always trying to support to a younger musician like me by showing the wise side of his personal experience, on the other hand, he was not scared to also show his fears and weaknesses when faced with hard music or life challenges.

I was once talking to a staff member in the Juilliard Jazz office that I had't seen in a while and, as I was about to say goodbye to her, I said "See you soon Rebeca. Think about me sometimes...," he walked in just at that moment, a big smile appeared on his face and he said "Aaaaaaah Luca, I like that, I am going to write it down to use it later. You Italian men!." And that's what he started telling me after we would meet "Luca, think about me sometimes (smile)" .

Yes Frank!. I will. Count on it.

Maria Schneider

Frank's life is an example to us all. His art reflected his life, and his life reflected his art.

Frank's life is an example to us all. His art reflected his life, and his life reflected his art. He was always operating on a "relaxed" mode that I so wished I could find for myself. If there ever was someone who savored the "here and now," that was Frank.

Though he was insanely knowledgeable, his artistry was led by some kind of incredible trust in what each moment would bring to the music. Over the years, I've heard him invent hundreds of intros from that magical place, on the fly, that were as sophisticated as any Debussy prelude.

I've heard him play endless transcendent solos, and heard how exquisitely he accompanied others, listening with his incredible ears and with his very big heart. His respect of bandmates was unmatched, his skills in listening were profound, and his joy in making music was beyond evident.

Whether you were making music with Frank, or sitting in the audience taking it in, Frank exuded love and joy: for the music, and for those moments of deep connection with musicians and an audience.

Frank was a blessing for the music community, and inversely, Frank's life was clearly made full by the incredible like-minded artists that he also got to make music with.

What a privilege it was to have been one of those musicians lucky enough to have shared music and friendship with him.

Kendra Shank

It's hard to fathom a world without Frank Kimbrough in it.

It's hard to fathom a world without Frank Kimbrough in it. To me he was band mate, friend, mentor, inspirer. 28 years of playing and recording with him helped shape my approach to music. Keeping it fresh, allowing the music to unfold organically, with in-the-moment "arrangements" formed spontaneously on the bandstand, conversationally. Deep listening and connection, absolute trust of everyone in the band, embracing the unknown, taking risks, playing space. On a ballad it felt like he knew what I was going to sing before I sang it, laying out beautiful harmonic stepping-stones in my path, or extending a musical hand for me to grasp, inspiring note choices I otherwise might not have accessed. A conversation, a dance, tender, sensitive.

I learned so much from Frank and I'm so grateful and fortunate to have had him as a musical partner and friend. We met in 1992 when Shirley Horn brought us together to play a short set between hers at the Village Vanguard, along with Ed Howard. It was my first time in New York City. I was extremely nervous and Frank was so kind.

Years later, in another moment of nerves, Frank said to me "It's just music, nobody's gonna get hurt" and "There's a reason it's called PLAY-ing!"—that lightened me right up. So many wonderful memories of gigs, moments on the road, stories he told, his sense of humor, are flooding my mind. Too much to tell.

I will miss him terribly, but I will carry his spirit with me.

Mark Sherman

The passing of Frank Kimbrough came a shock to us all. In addition to playing with Frank many times in my own quartets and in other groups, like the Ron Horton tentet dedicated to the music of Andrew Hill, and on many other Juilliard events, I taught in the next room to Frank at Juilliard Jazz for 13 years. Talking music, students, and politics with him was always enlightening.

The passing of Frank Kimbrough came a shock to us all. In addition to playing with Frank many times in my own quartets and in other groups, like the Ron Horton tentet dedicated to the music of Andrew Hill, and on many other Juilliard events, I taught in the next room to Frank at Juilliard Jazz for 13 years. Talking music, students, and politics with him was always enlightening. Frank was the ultimate purist in our music. To reflect his dedication and purist approach to the piano and the music, I share a story Frank told me that is quite amusing and reflective of just how dedicated to the piano, and the music Frank was.

In his words...:

"When I first came to New York I arrived with no piano. Someone gave me a Fender Rhodes electric piano to use. On my first gig I got in New York I dragged the keyboard to the gig. After the first set, or maybe it was the end of the gig, I was outside smoking a cigarette thinking about how much I hated playing the electric piano. It was at that point that I just said to myself... 'Fuck this' and I left and went home.

Basically Frank left the Rhodes at the venue and never came back. Most people would value the Rhodes for the money it costs, and some like playing it. Not Frank... he hated anything but the "real" acoustic piano.

His purest attitude shines through in the huge body of work he has left us, culminating with the box set Monk's Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk, an incredible documentation of Monk's music. In addition, Frank loved, and was loved by, all his incredible students of which many have come to the forefront of our music.

It is with great sadness that I say "another great one has translated..." RIP my brother Frank. You will be missed forever.

Satoshi Takeishi

Sometimes, a small gesture can leave a deep impression that will last forever. It's like a seed of someone's soul which remains inside of you and helps you remember the essence of that person.

Sometimes, a small gesture can leave a deep impression that will last forever. It's like a seed of someone's soul which remains inside of you and helps you remember the essence of that person. One day, after a gig we played together, Frank came over and gave me a heartfelt hug. And in that simple hug, he left something in me that I continuously think about. About how we treat each other as musicians and as human beings.

Frank was not only a great musician but a kind, humble and soulful man. He treated everyone with respect and love. And above all, he shared his wisdom with many of us who came in contact with him, compassionately and gracefully.

With that hug, he left me not only a warm memory of him but also a wisdom that I will continue to strive for...

I'll miss you Frank...

Micah Thomas

I'm trying to think of some great single story to tell, but whenever I think about Frank, a lot of little moments come to mind instead.

I'm trying to think of some great single story to tell, but whenever I think about Frank, a lot of little moments come to mind instead. I think about him coming to so many of my gigs and, whenever a particular band or gig excited him, sending me an email that night or the next day telling me how much he enjoyed it and how we should continue playing together. He would also tell me, in our lessons, whenever he had heard another Juilliard student play something he really loved. He hired many of my classmates for his own gigs, and while these were of course mentoring opportunities, it also felt that he genuinely just liked their playing so much that he really wanted to play with them. He was also quick to complain about whenever he found something pretentious or superficial—he longed for honesty in music and in life always.

I also think about our lessons, which were often me playing tunes for him and us talking about it afterwards. He acted like my conscience and would tell me when the way I played something was or wasn't up to par with what he believed my standards to be. Sometimes he would suggest a specific solution for improving my performance, but just as often there was an eventually implicit understanding that the solution to playing a tune better was often simply spending more time with the tune or understanding it better in some way that I would have to find myself. Even though he's gone, I can still hear him approve or disapprove of what I'm doing in my head, and I trust his voice more than most people's because we shared many of the same musical values.

It's hard for me to think of a particularly interesting story about Frank because Frank thrived on simplicity in every aspect of his life. He walked slow, talked slow, and played slow. One of his favorite things to talk about doing was to go to the park, take his shoes off, and lie in the grass. The people that he adored and talked about so often, like Shirley Horn and Paul Bley, were often people who lived crazy lives, and he loved telling exciting, often scandalous stories about them. He really liked the opportunity to say something or advocate for something that was contrary to the ideological environment he was in—he was something of a rebel by nature. But, while he had so many crazy stories about other people, he seemed to purposefully keep his own life as simple as possible. A quiet rebel.

I sent him my album to listen to while I was deciding whether or not to release it. He told me that often, when he was listening to music in his house, his wife Maryanne would come and listen to a song or two and then go back to whatever she was doing before. He noted that when he played my album, she listened to the whole thing. It was really touching to see how much Frank respected her opinion and looked for it. Their kind of relationship, from what I knew about it, was something that I would want for myself and my partner one day. Frank plays her composition "Solstice" on his album by the same name, and it is one of my favorite tracks he ever recorded.

The memory that I think of the most is the day that he finally let me pay for his meal, instead of him paying for mine like he used to do whenever we went out to eat. It was my last year of college, and we had been spending more time together than usual because he was helping me through the process of preparing for the release of my album. Our conversation was different than usual, less of a teacher-student quality and more of a peer-to-peer quality, and he even noted that this was happening. When he allowed me to pay for his meal, it felt like we had finally become friends. I wish I could have spent more time with him as I continue to grow up.

Ryan Truesdell

For the more than seventeen years that I was fortunate to know and work with Frank, we amassed countless stories together. Whether we were on tour, at a session or a gig, or just hanging out discussing music and beyond, time spent in Frank's presence was always special and memorable.

For the more than seventeen years that I was fortunate to know and work with Frank, we amassed countless stories together. Whether we were on tour, at a session or a gig, or just hanging out discussing music and beyond, time spent in Frank's presence was always special and memorable. As I've reflected on our myriad experiences together, one memory that continues to bring me comfort, is from my first tour as road manager with the Maria Schneider Orchestra in 2008. My first time traveling with the band was a pretty intense tour all over Europe: 12 concerts in 14 days over seven countries. The tour started out just as many musicians would expect from this type of "road story." Everything that could have gone wrong, did: lost luggage, instruments, and music; airlines going on strike; stranded musicians; needing to find temporary replacement musicians in small cities in France at the last minute; difficult promoters... you name it. As the tour manager, finding solutions to these issues rested squarely on my inexperienced, 28-year-old shoulders. It was stressful, I didn't sleep much, and my confidence in my ability to successfully manage the tour (already shaky at best) was diminishing with each new curveball.

Around the half-way point on the tour, we arrived in a small German town for a concert that evening in an outdoor park pavilion. In keeping with the theme of the tour, this particular gig provided yet another batch of unexpected challenges. It had been a long and grueling tour for everyone already (great music, though! Those kinds of tours always result in the best performances) and as the day progressed, I could feel myself reaching a mental and physical breaking point.

When I got back to my room after the gig, I remember sitting on the foot of the bed for a moment in the dark, doubting my abilities, and questioning whether I had the strength to get through the rest of the tour. Right then, my room phone rang and it was Frank. Of course, my tour manager mode was triggered—assuming something was wrong—but Frank just said, "How you doing?" followed by, "You wanna go for a walk?" We were both exhausted from traveling, Frank had just performed, and we had only a handful of hours to sleep before we had to be back on the bus for the next gig, but at that moment, I couldn't think of anything I'd rather do.

We leisurely strolled around that old, quiet town for well over an hour. Maybe more. We discussed the concert that night, and other amazing musical moments from the tour. We talked about life and politics and a variety of other non-music related topics as well, though I don't specifically remember what exactly. What I do remember is the feeling of my stress lifting as we walked. Inadvertently and unintentionally, Frank was pulling me out of my head, out of the stress and anxiety of the first part of the tour, and into the present moment. Everything else seemed to just fall away, and the only thing that mattered was this walk and this conversation with Frank. As we made our way back to the hotel, without prompting, Frank told me what a great job he thought I was doing on the tour, and that he was proud of me. I remember trying to brush it off in the moment, saying that I was just trying to do my best, but Frank was insistent: he even recounted specific situations in which I had handled myself well.

That night, I slept better than I had in weeks. I had no idea when I accepted Frank's invitation, what a lasting effect that walk would have on me—in the moment and in the future. Whatever we talked about that night, what stuck with me was the knowledge that Frank Kimbrough, a musician I idolized and whose friendship I cherished, was proud of me and what I was doing. That is a feeling I'll hold close for the rest of my life.

In the years since that tour, and throughout the various projects we've done together, Frank's support of me has been unwavering. Whether it was planning and managing other tours, time spent producing in the studio, writing my own music, or leading the Gil Evans Project, he was always there for me, both personally and musically. There is no other pianist out there like Frank, and I can't begin to describe the gift that he has given the world with his music, but I truly believe his most meaningful legacy will reside within walks like the one we took together in Germany. He was endlessly inspired by the young, eager students that surrounded him at Juilliard, most of whom I guarantee have been on similar walks with him around the Upper West Side or Queens. I don't need to know what they talked about to know that they left each hang with Frank feeling the full support and pride he made you feel in his presence. Anyone can teach you how to play a tune or show you how to voice a chord, but few people are able to selflessly raise you up, support, guide, and inspire you the way Frank did. He was that person for me from the beginning (though I might not have realized it till that walk in Germany) and will continue to be that for me for the rest of my life. I hope he knew how much I cherished that late night walk in Germany, and every walk that followed.

Thank you, Frank, for being the mentor, the foundation, the friend that I needed, and for the beautiful, unforgettable music you brought into my life.

Immanuel Wilkins

Frank Kimbrough was my teacher at The Juilliard School. He was like an uncle to me and deeply cared for all of his students. He believed in me often in times where I felt like an outsider, and he was a wealth of knowledge.

Frank Kimbrough was my teacher at The Juilliard School. He was like an uncle to me and deeply cared for all of his students. He believed in me often in times where I felt like an outsider, and he was a wealth of knowledge. A lot of what makes jazz music special is the oral tradition of passing down stories. Frank loved to tell me hour long stories about Paul Bley, Andrew Hill, Thelonious Monk. I fondly remember him once telling me he had just finished playing "'Round Midnight" in a practice room for 12 hours straight.

Me and Micah Thomas would always joke about the crazy things he would tell us as we'd often play in each other's lessons with him. He introduced me to everybody on the jazz scene and he's responsible for so many of the relationships I have today. Frank was generous.

Every time I would see Frank he would always say something about the shoes I had on and we would often talk about clothes. The last time we spoke on the phone it was him calling to tell me about this baaaddd coat that Andrew Hill had given him and how proud he was of me.

When I look back on our relationship, I think about the boundless support he gave me in all aspects of my life, I hope I continue to make him proud.

Matt Wilson

"How Ya Doin'?"

"How Ya Doin'?"

Tags

Profile

Frank Kimbrough

Ludovico Granvassu

Carl Allen

Herbie Nichols

Paul Motian

Ben Allison

Thelonious Monk

Andrew Hill

carla bley

Annette Peacock

Hampton Hawes

Jay Anderson

Paul Bley

Charlie Haden

duke ellington

Anette Peacock

Matt Balitsaris

Ted Nash

Noah Preminger

Scott Robinson

Rufus Reid

Billy Drummond

Jeff Ballard

Dave Ballou

Michael Blake

Jaki Byard

Don Pullen

Ron Brendle

Katie Bull

Steve Cardenas

Patrick Cornelius

Jeff Cosgrove

John Hebert

Martin Wind

Ed Schuller

Tim Horner

Evan Harris

Jeff Hirshfield

Ron Horton

Rich Rosenzweig

Ed Howard

Paul Bollenback

Steve Williams

John Schroeder

Maryanne DeProphetis

Bill Evans

Micah Thomas

Immanuel Wilkins

Landon Knoblock

Ben Monder

Tony Moreno

Elan Mehler

Jimmy Mcbride

jason moran

Riley Mulherkar

Shirley Horn

Matt Munisteri

Sara Caswell

Ben Rosenblum

Luca Santaniello

Maria Schneider

Kendra Shank

Mark Sherman

Satoshi Takeishi

Ryan Truesdell

Matt Wilson

Steve Wilson

Christopher Ziemba

Andy Zimmerman

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.