Home » Jazz Articles » Big Band in the Sky » Frank Kimbrough: From Now to Forever—A Remembrance

Frank Kimbrough: From Now to Forever—A Remembrance

I often would give a ride home to Frank after a gig in New York City. We would talk all the way to his place and then often sit in the car and talk for another hour (or more). My nights were pretty short back then with four young children but I do not regret taking the time to share our human moments.

Frank and I had a bit that when we saw each other our salutation would be "How ya doing?" in a very clipped and over the top Brooklyn accent. A few weeks ago, I was listening to the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC and someone came on and greeted Mr. Lehrer with a classic, "How ya doin'?."

I immediately called Frank. We visited for awhile but he had a student. We ended our visit the way we always did, by saying, "I love you."

When I received the call yesterday from Ted Nash, I just broke down. Frank was dedicated to the music but, more importantly, he was devoted to the people of his community. He cared. Frank really cared.

Frank conveyed to me one night in one of our talks in front of his apartment, how much his students at Juilliard meant to him. He expressed that he felt his legacy would be the opening of the spirits and sounds of young musicians. I believe he did that for all of us in his orbit.

One night we were playing and we were seriously in the flow zone of offering and receiving sounds and spirits. Frank told me afterwards, "Matthew, it is one thing to share sound together but to share space? That is the magic." Frank Kimbrough shared sound and he shared space in music and in life. I am grateful for his influence in my life.

I am glad I called with the "How ya doin'?" and we shared another, "I love you."

Thank you Frank Marshall Kimbrough, I love you.

Steve Wilson

Frank was the embodiment of integrity. You always knew where he stood on any subject or issue, and he was uncompromising in his artistry and humanity.

Frank was the embodiment of integrity. You always knew where he stood on any subject or issue, and he was uncompromising in his artistry and humanity. Frank would just informally go about his way of creating and playing the music that he believed in without any pretense, fanfare, or self-aggrandizement. He could take the simplest theme and transform it into the most incredible sound mosaic, and do it differently every time.

He hated to rehearse for his own dates—just relished being in the moment with musical partners that he loved and trusted. One of my favorite tunes is his "Kudzu" (which we recorded on his Quartet album on Palmetto) which is a soundscape of the Southern roots that we shared, and it hits you just right in your soul.

We will miss his originality, spontaneity, kindness, and heart. Though he has left us with a substantial body of work to enjoy and admire Frank's spirit always will be with us in real time.

Christopher Ziemba

Frank Kimbrough was truly one of those once-in-a-lifetime type of figures. The sort of person who could leave an indelible impression on anyone he encountered. I had the great fortune to be counted among Frank's piano students during my two years at Juilliard, and for me, he made so much more than an impression. In fact, it wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that knowing Frank so thoroughly and positively influenced the course of my life that I simply can't imagine what an alternate, Frank-less reality might have looked like for me.

Frank Kimbrough was truly one of those once-in-a-lifetime type of figures. The sort of person who could leave an indelible impression on anyone he encountered. I had the great fortune to be counted among Frank's piano students during my two years at Juilliard, and for me, he made so much more than an impression. In fact, it wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that knowing Frank so thoroughly and positively influenced the course of my life that I simply can't imagine what an alternate, Frank-less reality might have looked like for me. Where would I be? What would I be doing? I can't imagine. If I had never met Frank and taken that trip to New York City to get a one-off lesson with him, I never would have thought I could get into Juilliard—who knows, I might not have moved to New York City at all—and certainly wouldn't have had any of the opportunities that came as a direct result of having him as a mentor (my first gig at so-and-so club, recommending me to play with such-and-such big name player). Sometimes I even wonder if I would still be a jazz pianist today! Frank played a huge part in shaping the course of my life, and I won't get to tell him how immeasurably grateful I am.

Such a loss cuts deep... the loss of a close friend or family member. Frank felt like both to me, and in the wake of his sudden passing, it's easy to fall into the trap of thinking that we are now, all of us, Frank-less. However, in hearing and reading tributes, memories, and anecdotes from his other students and colleagues, I've found that the grief has been softened by a confident faith that Frank lives on!

Such a singular personality touched so many lives so deeply, that we all now carry him with us. I think I can probably speak for all of his students when I say that Frank's essence continues on in our hearts and minds: his opinions on music; keen observations on politics; his stories about the New York jazz scene from decades past; crotchety words of wisdom passed down from his own once-mentor, Paul Bley; his dark humor. In short, Frank had already become a legend before his time on earth was through! This, of course, says nothing about his vast recorded oeuvre, as full of breadth and depth as any artist could hope to leave behind.

One of the things that made Frank so special was his willingness to impart himself to others. Wisdom about music, wisdom about life. Lessons with Frank took place as much at the piano as they did away from the instrument... and when we were away from the instrument, we were walking and talking. Even when I was out of school, the walks always started outside the main entrance to Juilliard on West 65th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam. (As I'm writing this, I'm picturing the way I'd almost always find him: standing right at the curb in front of those doors, often sporting a trench coat or leather bomber when the weather called for it, a colorful button-down, always with those dark circular spectacles, a lit cigarette at hand, and a nonchalant posture that said he knew just how damn cool he was. He was also almost always found engaged in conversation with another passerby; Frank's cool guy vibe was an outer shell for a warm and inviting soul.) Walks would go up, down, left or right, but there would be some usual destinations. Most often, we'd go for the sushi lunch special at Amber, up on the corner of 70th and Columbus. (Frank was such a regular here that all he'd have to do was walk in, and the servers would all greet him by name. He even had a "usual" that he ordered!) Just a few short blocks, pretty much as short as a walk was liable to get in New York City, and yet this walk would become a journey in itself.

With Frank, walks were never a means to an end, they were as much an integral part of the hang as the time spent sitting at the table. These walks were not typical to the streets of New York, either; there was no rushing, no jostling, none of the usual vying for position at crosswalks. Frank didn't play that game. I always got the sense that Manhattan was moving around and in spite of Frank, and that he was determined to only ever go at his own natural pace. It was a slow pace! Possibly a holdover from his North Carolina upbringing, but it was also more than that. Simply observing Frank during these walks, I quickly learned that here was a man who had decided to be fully committed to the present. He was in the moment, and so immovably in the moment that whoever he was with was forced to enter this same moment and share in its significance with him. When walking with Frank, I noticed things more. The blinders came off, and this allowed the sights, smells, and sounds to make themselves known.

On one of my very first walks with him to Amber, he hipped me to the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, or fleeting glimpses of beauty to be discovered in the transient imperfection of nature. (This could apply to anything... a particular pattern of footprints in the snow, the way leaves might swirl when caught up in a gust, or even the way the sun might reflect off of a group of yellow cabs waiting at a light). You couldn't find it if you were searching for it, but you had to be open to noticing it when it was there. With this in mind, I learned that even walking to the end of a block could become an opportunity for revelation and inspiration.

I realized then that Frank was "on another level," that Frank had somehow figured out the secret to living and experiencing life to its fullest. He just had an undying positivity, an ability to always find the bright side, to see the larger picture, to not let himself be bogged down by petty concerns... and to walk with Frank was to become infused with this same spirit! My concerns about navigating the bridge to a certain tune, finding work as a new guy on the scene, playing poorly the night before (definitely a recurring frustration of mine), whatever new bad geopolitical thing I read in the news... with Frank, these worries all were framed differently. I could approach these issues with a healthy perspective, because Frank taught me not to dwell on the problems. I had determined almost immediately to make myself more like him, to soak up as much of his vibe as I possibly could... one walk with Frank was apt to inspire me for weeks on end. (How lucky I was to be able to a weekly dose when I was in school!) I'm not sure if Frank ever realized how much help he was to me, or just how much of a guiding light he could be to those who had not yet achieved his ability to float above the storms.

Other common destinations with Frank were Central Park, where we'd find a bench on which to just sit for a while and watch things go by. Frank revealed that he sat on benches a lot. "I never practice," he would say. The bandstand would just render irrelevant and useless any of the constructs of the so-called practice room, anyway. All the preparations he needed to make were done in his mind, on a bench surrounded by trees, squirrels, distant city noises. When Maria Schneider sent along a piano part for a new tune, he'd take it to a bench and read it over and over until he knew it. He also came up with entire compositions, or arrangements of standards, in the park. One that I'll never forget is his twisted take on Jerome Kern's "All the Things You Are..." Somehow, he realized you could play the second eight bars first, followed by the first eight bars, then the second half of the bridge followed by the first half of the bridge, and then the last section as is. Only a few connective chords were needed and he had found a brand new take on one of the most well-worn vehicles in the jazz pantheon.

In an effort to be more like Frank, I started seeking out some spots of my own to take a break. Though I never quite got to his level of sitting and simply thinking or being, I made a point to listen to full albums all the way through and had begun to learn to focus my attention for extended periods. At times we went to one of the last remaining true record stores in Manhattan, Academy Records & CDs on West 18th. They have a jazz section that would take more than an hour to browse through, and Frank would pick out some obscure recordings that I'd never checked out or even heard of, and you'd better believe I bought them then and there.

During these walks, it felt like Frank had welcomed me into his sphere. I always sensed in those moments that I was special, that Frank had wanted and allowed me to share in the present with him. And I think that this was true; conversations rarely felt as meaningful, or as sincere, or as thought-provoking as those with Frank. I knew that he sincerely cared about my development as a human. This is the sign of a truly great teacher. I've heard these same kinds of things expressed by some of his other students as well. He devoted himself to us. He was able to make each one of us feel important in the moment, and feel the importance of the moment. He had many current and former students to walk with, yet Frank always found time for everyone, and he never brought anything less than his whole presence to each person. He was, simply put, as real as it got. I will always marvel at his ability to be completely and undeniably himself at any juncture, in person or at the piano.

A new chapter began in my life when I moved away from New York City, after six wonderful years spent in and around that scene, to Washington, D.C. I am lucky to still be pursuing music (and jazz, at that), though the move itself and having made the choice to head away from the epicenter of my art had the predictable effect of causing me to question my choice.

Inspiration was no longer as easy to come by, because I couldn't go to a Smalls or a Village Vanguard on a whim. Frank became a lifeline for me. Every few months, I'd give him a call at his home and we'd catch up as if no time had passed. I'd fill him in on what I'd been up to, he'd tell me about where he'd been playing, how his current students are, we'd complain some more about the political environment. Eventually I'd bring up how I was struggling to stay inspired, how my playing had taken a hit, how I just felt off since leaving the City. Frank, true to form, would always call my bluff. He broke down the BS in my head with a healthy dose of perspective. "Remember, you're the only person that's ever heard 100% of what you played." Or, "When you walk out on that stage, you have to tell yourself that you're the baddest motherf*cker that ever played. That's what I do." Or, "As soon as the gig's over, forget about it. It has nothing to do with the next one."

Sometimes he'd reference the period when he'd just gotten to New York, had few possessions of his own and was practically squatting until he got the call from Maria. Sometimes he'd recall that gig where he lugged his Fender Rhodes into a cab, brought it down to some club, played the first set and decided he'd endured one too many injustices to merit continuing. (He quit after the first set, left his Rhodes there and never looked back.) Sometimes he'd tell that story about getting to a gig and the bassist had gotten so hopped up on substances that he had climbed a tree outside and refused to come down to play.

Even months apart as the phone calls were, I would hang up feeling completely refreshed and rejuvenated, as if I had just had one of those weekly lessons followed by salmon avocado and shrimp tempura rolls. I always meant to bill him an invoice for the therapy he was unknowingly providing. When the pandemic hit, and I found myself without an outlet for the thing I had trained my whole life to do, Frank was there for me still, floating above it all and seeing the whole picture. About a month in, our first talk had centered around the new gig-less pandemic landscape, about which I was recognizably dark and had been on the verge of falling into a "what's the point" mindset towards practicing or even listening to music. Frank had again turned me around, pointing out that it would only be temporary, and recommending that I re-read one of his favorite book recommendations: "Free Play" (by Stephen Nachmanovitch, about kindling and maintaining one's innate spirit of play).

We spoke once again, and for the last time, in October. He'd left me a voice message to check in, to see how things had been faring. We chatted for close to an hour, and he said he'd been continuing to enjoy his walks in the park and spending time with his wife Maryanne. I distinctly remember his sign-off: "Okay, love you, man, take care of yourself. Talk to you again soon." I couldn't have known that would be the last time I'd get to speak to him.

So, to Frank: Thank you. Thank you for your music, your piano playing, your compositions. Thank you for your many words, in the form of piano lessons, life advice, jazz lore, jazz departmental gossip and dark jokes. Thank you for always, always being willing to make time for a hang and a walk. Thank you for fostering my love of sushi. Thank you for being so generous with passing my name around town when I first got there. Thank you for supporting my development and then being a trusted ear for my concerns. Thank you for showing me that it's all about taking the journey, and that the perceived end goal is never as important as it may seem. Thank you for teaching me how to appreciate life. Thank you for everything.

Andy Zimmerman

Frank was one of the main fixtures of my time as a young man in New York learning to play jazz. He was someone that you would run into seemingly everywhere you went, around the halls and practice rooms of the music building, or outside the building on 4th Street where the jazz kids would congregate and smoke, or over at Tower Records at 4th and Broadway on a dark Tuesday evening, or even at more random locations around Manhattan.

Frank was one of the main fixtures of my time as a young man in New York learning to play jazz. He was someone that you would run into seemingly everywhere you went, around the halls and practice rooms of the music building, or outside the building on 4th Street where the jazz kids would congregate and smoke, or over at Tower Records at 4th and Broadway on a dark Tuesday evening, or even at more random locations around Manhattan. Wherever it was, it was never a surprise. More often than not those chance meetings turned into hour-long discussions about music and musicians. Frank always had time to talk to us. He would indulge us with story after story about gigs, recordings, musicians, food, whatever. He was one of the great keepers of jazz mythology and he didn't miss a chance to pass it on to us. And we ate it up. His pacing, his accent, his expressions, his absolute conviction. The way he would deliver that last line of the story and then slink away with that cat-like grin, that knowing stare, that funky strut.

Very early in my time at NYU I had to take a piano class that was required of all non-pianists. It took place every Friday morning at 8 AM and the teacher was none other than Frank Kimbrough. I was 19 years old, completely naive, and completely unable to get myself out of bed for this class. I went to the first two sessions, but after that I didn't return until the final exam, which was simply to play any jazz tune on the piano in a room alone with Frank. I stayed up the entire night before the exam learning the Monk tune "I Mean You," which I ended up completely butchering because I was exhausted, nervous, and unprepared. I don't think I finished playing the tune. It was more like I reached a point where the feeling of shame eclipsed whatever little forward motion I had and I just stopped. Frank immediately layed into me with a speech that I'm sure other of his students would recognize, that I'm not in Missoula, Montana, shaping myself into a fully formed jazz musician. I'm in New York fucking City where you can't afford to make a bad impression because people are watching, important people who know what a half-assed effort looks like.

Nearly two decades later I was given an opportunity to spend a couple days in the studio making a record with Frank. We would record some of his tunes and maybe a couple standards. There would be only one rehearsal. The sheet music would be emailed to me just days before that rehearsal. Other than Frank I had never met anyone else in the band. These were not my preferred conditions. My anxiety grew and grew, and even when we were well into the first day of recording it was apparent that I wasn't relaxing into the experience, rather I was reverting to that nervous, unprepared, shameful state of mind that he had witnessed long before and that he very easily recognized. We were working through a tune of Frank's called "Elegy for PM," a ballad with a tempo that quickened and slackened with the arc of each melodic phrase. It was clearly a situation where I had the melody and I had to take the lead and drive the phrase forward, but I was failing to do so.

"Take the lead and sing it out, Andy. You're Caruso," he said to me in between takes.

"I don't know," I replied. I didn't feel very Caruso-like.

"You're a bad motherfucker. You're a bad motherfucker from Chicago," he said, adding some extra North Carolinian drawl the second time. And there was that cat-like grin, that knowing stare, the funky strut, and that absolute conviction in what he said.

It was enough conviction for both of us.

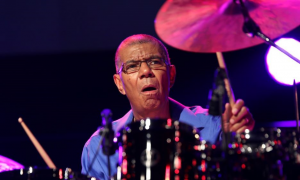

Billy Drummond

I first met Frank on a record date we both were on with Rich Perry. Then we met again when he came with Paul Bley to a record date I was on with Paul and Lee Konitz. But I really got to know him at Juilliard where we were colleagues. We discovered that we had a mutual admiration for some of the musicians I had recorded with (Paul Bley, Carla Bley, Stanley Clowell and Andrew Hill), as well as others like Paul Motian and Charlie Haden. We talked about music a lot. He loved teaching and was a mentor to a lot of students. He was really into it and into the students and they all loved him. He would come to school just to hang out even when he didn't need to be there so he was always in the halls. My main association with him was as the drummer on the Monk Project, Monk's Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk, which was recorded on three separate two-day recording sessions. We also had a little tour in the Azores and Portugal. He was a great musician and was great to play with because he could go in so many different directions. He was always in the moment and knowledgeable about music. I didn't know the extent of his compositional output until I was asked to play a track on the tribute album that was made after he died. That's how I discovered "Clara's Room" and then I decided to record it on my own album Valse Sinistre because I liked it so much.

I first met Frank on a record date we both were on with Rich Perry. Then we met again when he came with Paul Bley to a record date I was on with Paul and Lee Konitz. But I really got to know him at Juilliard where we were colleagues. We discovered that we had a mutual admiration for some of the musicians I had recorded with (Paul Bley, Carla Bley, Stanley Clowell and Andrew Hill), as well as others like Paul Motian and Charlie Haden. We talked about music a lot. He loved teaching and was a mentor to a lot of students. He was really into it and into the students and they all loved him. He would come to school just to hang out even when he didn't need to be there so he was always in the halls. My main association with him was as the drummer on the Monk Project, Monk's Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk, which was recorded on three separate two-day recording sessions. We also had a little tour in the Azores and Portugal. He was a great musician and was great to play with because he could go in so many different directions. He was always in the moment and knowledgeable about music. I didn't know the extent of his compositional output until I was asked to play a track on the tribute album that was made after he died. That's how I discovered "Clara's Room" and then I decided to record it on my own album Valse Sinistre because I liked it so much.

Tags

Profile

Frank Kimbrough

Ludovico Granvassu

Carl Allen

Herbie Nichols

Paul Motian

Ben Allison

Thelonious Monk

Andrew Hill

carla bley

Annette Peacock

Hampton Hawes

Jay Anderson

Paul Bley

Charlie Haden

duke ellington

Anette Peacock

Matt Balitsaris

Ted Nash

Noah Preminger

Scott Robinson

Rufus Reid

Billy Drummond

Jeff Ballard

Dave Ballou

Michael Blake

Jaki Byard

Don Pullen

Ron Brendle

Katie Bull

Steve Cardenas

Patrick Cornelius

Jeff Cosgrove

John Hebert

Martin Wind

Ed Schuller

Tim Horner

Evan Harris

Jeff Hirshfield

Ron Horton

Rich Rosenzweig

Ed Howard

Paul Bollenback

Steve Williams

John Schroeder

Maryanne DeProphetis

Bill Evans

Micah Thomas

Immanuel Wilkins

Landon Knoblock

Ben Monder

Tony Moreno

Elan Mehler

Jimmy Mcbride

jason moran

Riley Mulherkar

Shirley Horn

Matt Munisteri

Sara Caswell

Ben Rosenblum

Luca Santaniello

Maria Schneider

Kendra Shank

Mark Sherman

Satoshi Takeishi

Ryan Truesdell

Matt Wilson

Steve Wilson

Christopher Ziemba

Andy Zimmerman

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.