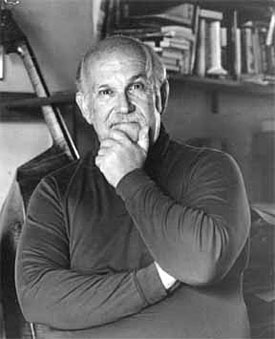

Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Bertram Turetzky: Contrabass Pioneer

Bertram Turetzky: Contrabass Pioneer

Moving To California, U.C.S.D.

Moving To California, U.C.S.D. BT: So then he called me and said they were starting a new music department at the University of California in La Jolla, and that I should come on out and show my stuff, he said, "I want you on the faculty." So that sounds exciting to me. I came out, I had picked up a concert at Pomona College, I stayed there overnight, and I drove down the coast the next day. It was March, and there were people in the water! I called my wife and I said, "Nancy, there are people swimming in the Pacific Ocean!" She asked me if I had been drinking! I told her she'll just have to see it for herself.

So, I came to UCSD, I found the place, I did an afternoon show that went well. I met Bob Magnusson. After the thing was over, the head of the department Will Ogden, says he wants to show me where my office is. I said, "You haven't heard my recital yet." He says they've had my recordings for years.

AAJ: So, did you say, "I'll take it" right there or did you need to talk to your wife first?

BT: In my heart I said this is it. I had to play my recital, and that went very well. Everyone was really nice and lovely. I stayed with the Erickson's that night, and Bob said, "You were terrific." I think I had his piece under control, and I played it, and that was super. So I told Nancy, "I think this is it. It's a chance for me to stay home more, see the kids, see you."

So she came out and we got some concerts, she saw some things, played at UC Davis, and did some television: San Francisco, KQED. So she liked it. We came out and I started to teach and it's funny, because everyone but me was already "California- ized," very casual. I was hilarious, I was color coordinated, I still tied my own bow ties every day. So again, more things are happening—recordings, concerts. Tracy Stern from Nonesuch Records came out, and they wanted a recording.

Stellar Students

Stellar Students AAJ: You had some prime students right from the beginning. Let's talk about a few, starting with Mark Dresser.

BT: Mark came out to see me at the Bass Club in L.A., and he liked it very much. I think I had a sul ponticello sound that reminded him of Jimi Hendrix or something, maybe to him. He liked the energy. So he came down and auditioned for me, and boy, he was really into it. I told him, "You're going to be a lifer," I think was the phrase I used. I told him I'd be delighted to have him as a student, and we've been friends ever since.

AAJ: Bob Magnusson.

BT: Yeah, he came for lessons, and he was so talented. So I took him through a lot of the classical stuff that I take everybody through, but he was so gifted. Such a wonderful guy. I hardly charged anyone much to study with me; I was still on East Coast money. I remember I hardly charged for my private lessons, but I enjoyed teaching very much. So Bob was lovely. Bruce Stone was there for awhile too.

AAJ: John Leftwich.

BT: John Leftwich! Oh my God! We had our moments. We started off very good, and, then, he became...John Leftwich! [laughter] We had some friction...over music, and what he should do, but he was already such a talented jazz player. So I said, "Look, if you want to finish your Master's degree, I think you should have a recital because then it'll be honest, and then you'll know that you earned it." And he fought a bit, but he did a very good job.

Then I didn't hear from him for awhile, and one day he calls me and said, "I hear you're doing a recital. Can I come? Take you out to breakfast after?" I said, "Sure, great." So we did that, and we had a very good time, and, he was very excited about the Tributes CD ( Nine Winds, 2005), he thought it was wonderful, he thought I should take some time off and just take it around the country to promote it.

But of course, I can't do that, I don't have the time. And I had John do a seminar for my last class at UCSD before I retired. He talked about being a freelance composer in L.A., and the things you had to do and how you had to do it. He was very impressive in that class.

AAJ: I never thought he got his due when he was in San Diego.

BT: Well, in San Diego, the heavy guy is Bob Magnusson. You know who I like a lot is Rob Thorsen, because he plays such good time—very good time. John played lighter, and Bob had the big ear of all of them, and he has this wonderful melodic gift, which I always loved.

AAJ: Your thoughts on Gunnar Biggs ?

BT: Gunnar came to me when he was in high school, and I thought he was very talented.

AAJ: He must have been if you accepted him while he was still in high school.

BT: Yeah, I accepted everybody. I felt it was part of being involved in the community. I want to be in the community, I want to help people. Gunnar, wanted to be a stage band director, so he went to North Texas State University. I said, "Why? There's no big bands anymore. What's the matter?" So, 18 months later, he came back and said, "Well, you were right." He's doing very well for himself now, he's got the gig with Peter Sprague.

AAJ: Kristin Korb?

BT: I got a call to do a week in Montana. The guy, my host said he wanted me to hear the big band. He said the bassist was very talented. So I listened to the band and they were pretty good, and I worked with them. I pointed out they have to have a rhythm section that helps lead the way, all that, what to listen for.

BT: I got a call to do a week in Montana. The guy, my host said he wanted me to hear the big band. He said the bassist was very talented. So I listened to the band and they were pretty good, and I worked with them. I pointed out they have to have a rhythm section that helps lead the way, all that, what to listen for. So she played for me and she was very talented. Very rough, but very talented. Nice ear, good girl and she was a wonderful salt of the earth person. So she said she wanted to study with me, I said, "Great," we figured it out, got fixed up, and I would give her a couple of lessons a week, because she had a lot of catching up to do. She had a good ear, but she had a lot of work to do. We did it and it worked out.

She taught at a college in Washington State, and they treated her very badly, so I told her to leave, it's not good to be where you're not wanted. So, she moved to L.A. started doing a lot of freelance work, her career really took off. Summer's she's going to jazz camp after jazz camp, she's worked with all kinds of people, including Ray Brown, she's made records, she's having a good life. She's terrific, and I love her. She's one of my most successful students.

AAJ: Speaking of successful students, Nathan East?

BT: He was at UCSD, and I bugged him about being a better reader. Well, he got up to L.A., and he said, "I should have worked on my reading more with you." I said, "Well, you're doing pretty good." He hears a tune once, [snaps fingers] that's it. Eric Clapton said he's like his brother. The kind of person Nathan is, when he started doing real well for himself, he took care of his folks. I tell that to my kids...[laughter].

Amplifiers. Solid Body versus Acoustic Basses.

Amplifiers. Solid Body versus Acoustic Basses.AAJ: Until the late '60s/early '70s, there wasn't much available in terms of amplification. In the old days, guys had to work at getting a big sound, or even just being heard. What do you think about the whole amplification thing, and how it's changed the instrument?

BT: Well, it's changed the instrument. In 1970, I went to a master class with Ray Brown. He said, "How many of you have played in a big band without an amplifier?" I raised my hand, and he said, "Turetzky, put your hand down" [laughter] He said, "Someday, amps may go out. What are you guys going to do?"

When I came here, I remember Magnusson said, "Oh my God, your strings are so high!" That's the way we played back east, strings very high. Now as the years have gone by, I've gotten older, and my string heights are probably at most California levels. But, with the amplifier it makes a lot of things possible. You're not killing yourself trying to pull the sound out of the instrument. And the sound is there.

I like to think that I get a mixture of wood—of acoustic sound with the electronic together. Bob, seems to like a little more of an electronic sound, have you noticed that? I think I have a darker sound. His is very bright. With John [Leftwich], he liked to play solos a lot of solos. So he did lower his strings quite a bit, and use his amp a lot— and some guys would say, "Hey, are you going to lay down some time, or are you going to play solos?" But John could do everything. He liked to play a lot of solos, and that's okay.

AAJ: What kind of pickup and amplifier are you using right now? Do you have the latest gear?

BT: Oh, no, no, no, no. I have this very old-fashioned idea. Look, you have your sound. You bring it with you wherever you go. So, I have a Realist pickup, I checked it out at Rice University, at a bass function.

David Gage asked me if I'd like to try it, I tried it. A couple of people came by and it sounded good. They both bought the pickup, so David laid a free one on me. Very nice of him. He's a very good guy, [it's] a good pickup. I have a, combo amp; I can't even remember what kind right now. I paid about five hundred dollars for it, and it suits me fine. I got my sound and my sound comes out when I use the amplifier.

AAJ: I read somewhere that you had four acoustic basses. Did you get rid of one?

BT: I have three acoustic instruments. Three, and they all do different things. That one [pointing] is an Italian bass from Venice, 1762. Very fragile, very beautiful. I'm going to do some classical music on it. The one in the middle, with the Lion's head, that's the one I got from the late Albert Stinson. You've heard me play that one. It's on most of the records. And the last one is from Germany, it was made by Gunter Krammer, he has two son's who also make basses.

He's retired several years back, but he knew that I liked that bass, and he had a picture of me in his shop. I've had the bass about thirty years now, and it's well broken in, and a lot of people have good feelings about that instrument.

AAJ: You've had several compact, solid-body instruments made for you. Are you happy with those instruments?

BT: Well, it's a compromise. It's a compromise. I mean, even to carry that bass there, [points to solid body], it's a drag to haul around. It works good with the rehearsal band. It works good with the Klezmer band. It has a good arco sound. I'm going to use it to play some dance music at the Musician's Union for the Jazz Artists Guild. I'm not going to lug the acoustic down there. I'll play the Azola, (solid body) for that.

I had one made for me a long time ago, [handmade by Dave Millard]. It didn't look very good, but it played good, and for the first time, I started to play sitting down in a regular chair. I thought hmmm, it didn't hurt my back. It was comfortable; I had something to lean against. I've been playing like that for many years.

A lot of people hear that [newer] bass and they think it's one of the best sounding solid bodies they've ever heard. It's an Azola, made by Steve Azola. He lives up near Julian. I became aware of them through Gunnar Biggs. He had one first. He was using it to play in the Starlight Opera and the conductor said it was okay. So I went, and played it with the bow, and it did sound good.

A lot of people hear that [newer] bass and they think it's one of the best sounding solid bodies they've ever heard. It's an Azola, made by Steve Azola. He lives up near Julian. I became aware of them through Gunnar Biggs. He had one first. He was using it to play in the Starlight Opera and the conductor said it was okay. So I went, and played it with the bow, and it did sound good. AAJ: Many bassists are always on a quest for a better instrument. What are your thoughts?

BT: Somebody told me a story: Julius Levine—who made more Schubert Trout Quintet recordings than any other classical bassist—studied with an old Jewish guy who was with the New York Philharmonic before it was the Philharmonic, whose name was Tiven, Julian Tiven. So in the depression, Levine wanted to buy a real fancy bass for about seven hundred dollars, which was a lot of money.

He took it to his teacher [Tiven], who said, "Julius, there's two kinds of basses. One is a fifty dollar bass; the other is a thousand dollar bass. I play the fifty dollar kind." Well, Julius bought the bass. He didn't understand [that] Jewish people have a way of talking that goes around in circles; sideways it's not direct.

AAJ: I guess so [laughter]. I'm still trying to understand what that parable means.

BT: Well, good. Let me tell you what I think it means. A great player brings his or her sound with them. And [Tiven] could make a fifty dollar bass sound like a million dollars. My teacher, David Walter, could do the same. I could make a pretty crappy bass sound pretty good. Not as good as those guys. It's not the bass, it's the player.

Peers and Contemporaries

Peers and Contemporaries AAJ: I'd like to get your thoughts on some other bassists. Whatever comes to mind. Charlie Haden?

BT: I know Charlie. Well, I knew him; I haven't seen him in years. Charlie Haden is one of the most original bass players. He is the epitome of less-is- more. The notes he picks are beautiful. Michael Moore - Clarinet once told me that his father, who was a jazz guitarist said, "Michael, it's not enough to play the right notes. You've got to play the best notes."

Charlie must have listened to Michael Moore's father, because he plays beautiful notes. He's got great time. His ear is just incredible. He hears things coming around the corner.

AAJ: David Izenson?

BT: We were friends. He studied with David Walter, my teacher. In fact, he used to come to Hartford occasionally and play in the symphony. He'd come to our house and eat, and change clothes and then we'd play the concert together. Yeah, we were good friends.

One time I was in New York, and he had gotten famous from playing with Ornette Coleman, and he came to my concert, and he gave me big hugs, and he had a full-length leather trench-coat on. In those days that was very...who would have such a thing? People asked, "Who is that guy"? I said, "That's David Izenson, my friend." Anyway, he gave me a kiss on the head, and told me I sounded wonderful. He was a great guy.

AAJ: What did you think of his playing?

BT: I liked his playing. I liked his playing very much. I think he took Ornette further out. Charlie grounded him a little bit with pedal tones and stuff. Dave really pushed him further out.

AAJ: Gary Karr?

BT: Gary and I are friends also and I admire and respect him very much. He has opened up a lot of doors for the instrument, and he's kind and generous. I don't know if I like him better as an artist or a person, and that's a high compliment.

AAJ: Edgar Meyer?

BT: I know Edgar a bit. I don't care much for the music he does, but he's a hell of a bassist.

AAJ: Gary Peacock?

BT: I haven't heard enough of him. Very interesting bassist. I like what I've heard. Yeah, I like what I've heard.

AAJ: Barry Guy?

BT: We're very good friends. We're very close. We exchange handwritten letters. In this day of e-mail, of course, I don't type, and he writes letters to me. And, of course, I have almost everything he's ever recorded. He sends everything he records over to me, and vice versa. We're very close friends. he follows American politics, I do too. In fact, I'm a little bit of a political junkie, so we have a lot in common.

AAJ: Dave Holland?

BT: One of my adult students got me tickets for the last time he performed here. He wanted me to see the show. While they're playing this guy says, "Look he's smiling at you." I figured he's just enjoying himself playing with his band. Well, at intermission, Dresser goes backstage and he comes back with Dave Holland ! He gave me a big hug, he remembered me and I remembered him.

When I first came here [California], one of the first gig's I got was at a Catholic girl's school, Sacred Heart, in L.A. I was doing my "show-and-tell" playing little things, and I saw a funky looking white guy—short, and a taller, equally funky looking white guy, and a totally disreputable looking black guy. Who the hell could they be? They didn't belong to this audience. Turns out it was Barry Altschul, Dave Holland and Anthony Braxton. (Chick Corea) was sleeping. They had the group Circle in those days. So, I met them all.

Then, after that, there was a move to deport him [Holland]. So he needed some letters of reference, and I was a professor, so I wrote him a letter. I said he was an absolute cultural icon, and he was going to just grow and grow. He could mean a lot to American musical culture. And we're friends for years now.

AAJ: One more. William Parker?

BT: I don't know enough about him to have an opinion. I saw him once with Cecil Taylor and I had no impression. But they say that his stuff is really heavy and powerful, and I just have to find time to listen.

With William Parker, I'd love to hear some of his stuff. But, he's a presence, I know that much. He's a presence.

AAJ: He's like the Ron Carter of free jazz.

BT: Yeah, that's a good analogy.

George Lewis, Triangulation II(Kadima, 2010). When you get guys like Vinny who works hard, I do, George Lewis does. The lazy people, who play just like they did twenty years ago, they don't interest me much. I like the guys who are always moving forward, always trying something new.

George Lewis, Triangulation II(Kadima, 2010). When you get guys like Vinny who works hard, I do, George Lewis does. The lazy people, who play just like they did twenty years ago, they don't interest me much. I like the guys who are always moving forward, always trying something new. AAJ: So this new record, does it have tunes, or is it all improvised?

BT : It's all improvised. But I listened to it many times before I sent it to Jerusalem, some of the stuff just sounds so compositional. One of the pieces, you see the three of us just get along like gangbusters. You know, I brought George to the attention of the university, and we're good friends.

So, the three of us, it's more than just comfortable, we have a lot of fun. So on one tune, I ask George if he had an idea, and he said, "Let's play a ballad, and let's start together." Not one word about notes, or a key or anything. And I listened to it, and it's like "Oh my God," it's like magic. I'm not exaggerating or bullshitting you. When you have good feelings, vibes, spirits, even love...

AAJ: So Lewis plays trombone, does Vinny play his whole arsenal?

BT: Pretty much. And he plays tenor saxophone on the ballad, and it's a lovely sound. He doesn't sound like any tenor player you've ever heard. Do you know Anthony Ortega? He's a dangerous improviser. I sent Tony a copy of Triangulation II, and he called me and said, "Man, that cat, every axe he plays sounds like it's his main instrument. Doesn't sound like no doubler to me." I told Vinny, and he was very pleased. He said, "That's a great compliment."

He's got it. He's got it. I mean, when you play with Vinny the communication, the lines of communication are remarkable. I hope people think I'm a good listener, but Vinny is a great listener. And there's things in that CD that just turn me around.

AAJ: You retired from UCSD in 2003. What have you been up to? Are you still teaching?

BT: Yeah, I have students who come during the week. I have gigs that I play. I played a couple of mainstream jazz gigs up in the Bay area a couple of weeks ago. So I still play a lot. I'm going to do a gig at UCSD with Mark Dresser, and I'm going to do something at Dizzy's [San Diego], with multimedia. I promised J.C. Jones of Kadima, the record label, that I would write an autobiography, so I'm working on that.

Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night and start remembering things, and I stay up and talk to myself until dawn. Then I get up and start writing things down [longhand]. My son typed some of it when I was up north; I stayed with him for a few days. I'm going to hire somebody to type the rest of it for me.

So, I'm working on that all the time, trying to get it finished. And, tomorrow, I'm going to watch some football. I do want to finish the book by the summer [2011], because I don't want it hanging over my head. I did do a DVD, I don't know if it's any good. I haven't looked at it yet. When I get some time, I'll drop it in the television and check it out.

I am active, is the answer. I've written a couple of pieces—I'm having them copied professionally. They are ethnic pieces, one was of love and loss for my mother, and the other one is for my father.

AAJ: Any other collaborations in the future?

BT : Vinny and I might do something more. Maybe with Bobby Bradford. Or, Braxton wants to play with us. Two bass saxophones and me. I'd like to play with Braxton. I think it would be fun.

I've played with Joëlle Léandre, I played with Barry Guy quite a few years ago. I've played with Barre Phillips, I've played with Mark Dresser quite a bit. There's some people. I'd like to play with Bradford, I'd really like to play with George Lewis again. I'm going to send Triangulation II over to a German festival to see if they'd like to bring us over. I would travel for that.

Selected Discography

Bert Turetzky/George Lewis/Vinny Golia, Triangulation II (Kadima Collective Recordings 2010)

Bertram Turetzk/Vinny Golia, The San Diego Sessions (Kadima Collective, 2009)

Bertram Turetzky, Tributes (Nine Winds, 2005)

Nancy Turetzky/Bertram Turetzky, Music for Flute and Contrabass (Nine Winds, 2001)

Bert Turetzky/Mike Wofford, Transition and Transformation (Nine Winds, 2000)

Bert Turetzky, Suddenly It's Evening (CRI, 1999)

Barre Phillips/Bertram Turetzky/Vinny Golia, Trignition (Nine Winds, 1999)

Bert Turetzky, Logs (by Paul Chihara. CRI, 1999)

Bertram Turetzky, Tenors, Echoes, and Wolves (Nine Winds, 1998)

Ed Harkins/Vinny Golia/Bertram Turetzky, Glossarium (Nine Winds, 1998)

Bertram Turetzky, Inflections I (New World, 1998)

Wadada Leo Smith/Vinny Golia/Bert Turetzky, Prataxis (Nine Winds, 1997)

Vinny Golia/George Lewis/Bertram Turetzky, Triangulation (Nine Winds, 1996)

Bertram Turetzky/Vinny Golia, Intersection (Nine Winds, 1996)

Vinny Golia/George Lewis/Bertram Turetzky, Triangulation (Nine Winds, 1996)

Vinny Golia/Bertram Turetzky, 11 reasons To Begin (Music and Arts, 1996)

Bertram Turetzky, Ais Nuema Records, 1994)

Bertram Turetzky, Compositions and Improvisations (Nine Winds, 1993)

Second Avenue Klezmer Ensemble, Traditions and Transitions (Second Avenue, 1992)

Bertram Turetzky, New Music For Contrabass (Finnadar, 1976)

Bertram Turetzky, The Contemporary Contrabass (Nonesuch, 1976)

Bertram Turetzky, Dragonetti Lives (Takoma Records, 1975)

Bertram Turetzky, The New World Of Sound (Ars Nova, 1969)

Bertram Turetzky, In No Strange Land (Nonesuch Records, 1968)

Bertram Turetzky, The Virtuoso Double Bass (Medea Records, 1966)

Bertram Turetzky, Contrabassist (Advance FGR-1, 1964)

Photo Credits

Pages 1, 6: Michael Klayman

Page 2, 3, 7: Courtesy of Bertram Turetzky

Page 4: Co Broerse

Tags

Bertram Turetzky

Interview

Robert Bush

United States

Ornette Coleman

Richard Davis

Joe Johnson

Carmen McRae

Mark Dresser

Bob Magnusson

Kristin Korb

Nathan East

Fourplay

john mclaughlin

Charles Mingus

Ray Brown

Vinny Golia

George Lewis

anthony braxton

Bobby Bradford

Fats Waller

Dave MacKay

Buddy Rich

George Duvivier

Dannie Richmond

Eric Dolphy

Charles McPherson

Lester Young

Jim Hall

Jimi Hendrix

Rob Thorsen

Gunnar Biggs

Peter Sprague

Albert Stinson

Charlie Haden

Michael Moore

Edgar Meyer

Gary Peacock

barry guy

Dave Holland

Barry Altschul

Chick Corea

William Parker

Cecil Taylor

Ron Carter

Tony Ortega

Joelle Leandre

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.