Home » Jazz Articles » Jazz West Coast » The Jazz West Coast Style of Music: An Introduction

The Jazz West Coast Style of Music: An Introduction

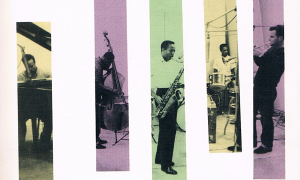

Courtesy Steven Cerra

It's why my dad relocated the family from New England in the closing years of that decade and as a budding Jazz musician, I took full advantage of it.

But so, too, did a lot of already established Jazz musicians, some of whom became my teachers. "The Left Coast" got a big boost from servicemen who remembered it from being stationed there on the way to their involvement in the Pacific campaigns of World War II. Army bases like Fort Roberts in San Luis Obispo county, Naval ports in San Francisco, Long Beach and San Diego and the US Marine Corps facilities at Camp Pendleton near Oceanside, hosted many soldiers, sailors, marines, as well as, army and naval airmen. The Coast Guard also had several bases in the state, notably in San Pedro. All of these military personnel got a first-hand look at California's charms and many gave serious thought to returning to the state to seek their fortunes once the war was over.

The employment needs of the war industries that dotted the state attracted countless numbers of civilian employees from all over the country to work in aircraft factories, naval shipyards and munitions installations. Many of these people sought permanent residence in the state after the war. The Big Band era of the 1930s and 1940s also brought many musicians to California to perform in its ballrooms, supper clubs and the occasional Hollywood movie.

Les Brown, Stan Kenton, Charlie Barnet and Woody Herman, were some of the bandleaders who became resident in the Golden State and although they toured nationally and hired musicians from all parts of the country, they took breaks in California between tours. For some it was a vacation; others had homes there.

Many of the New Englanders, Midwesterners and Southerners who were on these bands got a taste of life in California, a western U.S. state that stretches from the Mexican border along the Pacific for nearly 900 miles and its terrain which includes cliff-lined beaches, redwood forest, the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Central Valley farmland and the Mojave Desert.

In the 1950s, one could literally drive from the sea to the mountains and over to the desert in two-and-a-half hours.

After the fatigue of road trips in buses and cars set in, some musicians from these big bands took up residence in the city of Los Angeles, which, at the time, also happened to be the seat of the Hollywood entertainment industry.

Many of those who decided to put down roots in Los Angeles had two major underlying factors in common: a shared experience in some branch of the service during the war and playing time together on the big band circuit usually in the form of service on the bands of Barnet, Brown, Herman and Kenton.

In other words, they knew and respected one another and many developed close friendships as a result of these common experiences.

Once settled in Los Angeles, there was plenty of work close by at venues such as the Hollywood Palladium, the Hollywood Bowl, the Coconut Grove in the Ambassador Hotel, the Palomar, Avalon, Casino and Aragon Ballrooms, and the Shrine Auditorium. Even Disneyland got into the act with Carnation Plaza Gardens. Just "up the road" appearances were plentiful at the Golden Gate Auditorium in San Francisco and Sweets Ballroom across the bay in Oakland, California.

Many of those settling in LA were technically competent musicians whose years on the big bands helped them develop excellent music reading skills and these would become in high demand for studio work involving the recording of film and TV scores, TV commercials and radio jingles. Such studios were located throughout Hollywood and West Los Angeles and on the sound stages of MGM, 20th Century Fox, Warner Bros., Columbia, RKO and Universal Pictures.

In the 1950s, around the same time that musicians were looking to settle down and raise a family in Los Angeles, an affordable home building boom was taking place in the San Fernando Valley, a short drive northwest of the city, and in the central and southern parts of Los Angeles. Tied together by a massive freeway system, this meant that these musicians could access the studios in Hollywood and West Los Angeles in less than 30 minutes driving time, rehearse and record the various entertainment and advertising productions and be home in time for dinner, sometimes getting out early enough to pick up the kids from school on the way.

For those musicians interested in maintaining and/or developing their Jazz chops, the local club scene included the Crescendo/Interlude, the Lighthouse Cafe, The Haig, Jazz City, Shelly's Manne Hole, Tiffany's and Zardi's along with a host of neighborhood bars, lounges in bowling alleys and other, assorted watering holes which featured Jazz.

What evolved for these LA-based musicians was a lifestyle which derived from an environment that offered plenty of sunshine, modesty priced homes, some with pools where one could host a party of family and friends and serve meals from the ever-present barbecue grill, with plenty of work in nearby by studios, ballrooms, clubs and concert halls. If you will, one variation of the middle-class quintessential version of The American Dream.

Coupled with loads of positivity and optimism for the future which infused the country as a whole following the end of a world war that claimed the lives of 20 million people, it was a nice time to be alive, full of energy and enthusiasm and enjoying a comfortable life which was not always the purview of a Jazz musician.

Studio work was not everybody's "cup of tea." Thanks to a modest pay scale negotiated by Local 47 of the AFL-CIO Musicians Union, wages for a three hour recording session, or recording a 30 second TV commercial or a 15 second radio commercial jingle were certainly enough to pay the rent and the weekly food bill, provided that you knew enough contractors who could put enough hours together for you.

In the early 1960s, the scale for a 3-hour recording session [single instrument] was around $240 [or $80 per hour] before pension and health & welfare dues were taken out [it's almost double that today]. Certainly not a fortune but enough to subsidize the weekend $20 a night non-union gig [shush] at the local Jazz club.

Also the opportunity to record the work of composers such as Pete Rugolo, Henry Mancini and Jerry Goldsmith was certainly inspiring, but unless you were part of the inner circle of what ultimately became known as the Recording Musicians of America, a subset of Local 47, those gigs were few and far between.

And, of course, a very small percentage of recording work involved high quality music; most of it was work-a-day stuff, hardly as memorable as it was lucrative.

I will mention this aspect of the studio scene to reference it because in today's climate of everything race, sex and gender, somebody is sure to raise the question of why so few Blacks were involved in Hollywood-based studio work.

The most compelling answer to this question and the one hardly anyone expects is the simple fact that most Black musicians didn't want the work, preferring instead to make their living in the local Jazz clubs. And this attitude was also prevalent among some white musicians, too; both basically said they didn't want to play "that kind of music." [Cleaning things up a bit here].

And of course, there were some musicians who also couldn't participate in studio work because they were unable to read music or read it poorly.

There is no particular criterion for the selections included in the Jazz West Coast Reader or the order in which they are presented. I just picked narratives, commentaries and interviews that I liked, wrote an annotation for each to help point out what I thought was special about them and to help provide continuity between the pieces.

Chronologically, I will start the column with a narrative on the Central Avenue Sounds because this is analogous to what was going on with the Bebop movement along New York City's 52nd Street. Features on trumpeter, composer-arranger Shorty Rogers, tenor saxophonist, composer-arranger Jimmy Giuffre and drummer Shelly Manne follow because their departure from the Stan Kenton Orchestra to begin a residence at the Lighthouse Cafe with bassist Howard Rumsey's [an original Kentonite] All-Stars can be said to be "a" beginning of the West Coast style of Jazz. The short-lived Gerry Mulligan Quartet featuring trumpeter Chet Baker which performed mainly at The Haig might also be considered as another founding element in the style or school of West Coast Jazz, but all such demarcations are arbitrary at best.

It might be better to identify some of the defining characteristics of the West Coast style and these would include the fact that the role of the composer-arranger was given as much importance as that of the soloists.

For the most part, this music was not about playing the line [the melody; tune; song] and blowing [improvising] as many choruses as possible; executing the elaborate elements in the composition itself was as important as improvising on it.

And while the compositional integrity of The Birth of the Cool tunes influenced West Coast Jazz musicians, almost all of them also liked the Basie band's loose, free-flowing and understated sense of swing. Much of the music incorporated this "laid back" and effortless approach. But, while the Count relied on the Blues a great deal, West Coast Jazz was not particularly Blues oriented. Nor was it hard-driving. An aggressive approach to the time would have conflicted with the elaborate compositions that became a mainstay of the style.

This is not to say that what Bob Gordon labels a "hard style" of Jazz didn't also exist on the West Coast and the Curtis Counce Quintet, the Red Mitchell-Harold Land Quintet and even the Lighthouse All-Stars are examples of this approach.

A much more comprehensive explanation of the distinguishing features of the West Coast style of Jazz can be found in the following:

"West Coast jazz. A style of jazz, developed by musicians based in Los Angeles in the 1950s and related aesthetically to the COOL JAZZ movement. Much of it was played by professional studio musicians as an avocation. Their public performances centered on the Lighthouse club at Hermosa Beach and the Haig in Los Angeles, but a good deal of their work took place in studios, their recordings displaying technical sophistication, exploration of resources new to jazz, and high executive skill. Prominent among this group, both as performers and composers, were Shorty Rogers, Art Pepper, John Graas, Bud Shank, Shelly Manne, Herb Geller, Jimmy Giuffre, Carl Perkins, and Lou Levy.

Although some exceptionally spirited big-band music was produced, particularly by Rogers, the musicians worked mainly in small, experimental ensembles, emphasizing fairly elaborate, often contrapuntal, scores, yet leaving much scope for improvisation, which they sought to link closely to the written sections of their works. Their music was initially influenced by Miles Davis's recordings of 1949-50, later issued collectively as The Birth of the Cool, as is shown by such early West Coast performances as Rogers's Didi (1951, Capitol 15765) and Westwood Walk by Gerry Mulligan (on the album Gerry Mulligan and his Ten-tette, 1953, Cap. H439), but soon discovered directions of its own. Thus the West Coast players explored the jazz potential of serial technique, as in Rogers's Three on a Row, recorded on the album The Three (1954, Contemporary. 2516) by Manne, Rogers, and Giuffre; such works as Abstract no.1 (also on The Three), and Free Form, on the album The Chico Hamilton Quintet with Buddy Collette (1955, Pacific Jazz 1209), initiated the post-harmonic, collectively improvised music later associated with Ornette Coleman." -Max Harrison in Barry Kernfeld, ed., The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz [1994].

And, if you are interested in well-documented and detailed perspectives on West Coast Jazz or, as some prefer, Jazz West Coast, the subject has been well-researched and written about in Robert Gordon, Jazz West Coast: The Los Angeles Jazz Scene of the 1950s [1986], Ted Gioia, West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California 1945- 1960 [1992], Alain Tercinet, West Coast Jazz [1986], Alun Morgan and Raymond Horricks, Modern Jazz: A Survey of Developments Since 1939 [1956] and Gordon Jack, Fifties Jazz Talk An Oral Retrospective [2004]. James Harrod's Jazzresearch.com blog is invaluable as is his Stars of Jazz: A Complete History of the Innovative Television Series, 1956-1958 [2020].

Tags

Jazz West Coast

Steven Cerra

san francisco

San Diego

Les Brown

Stan Kenton

Charlie Barnet

Woody Herman

Shorty Rogers

Jimmy Giuffre

Shelly Manne

Chet Baker

Curtis Counce

Red Mitchell

Harold Land

Los Angeles

Art Pepper

John Graas

Bud Shank

Herb Geller

Carl Perkins

Lou Levy

Howard Rumsey

Howard Rumsey's Lighthouse All-Stars

Gerry Mulligan

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.