Home » Jazz Articles » Top Ten List » Top Ten Guitarists Who Left Us Too Soon

Top Ten Guitarists Who Left Us Too Soon

To narrow it down, any guitarist who reached the age of fifty was excluded from consideration. That eliminated two of my personal favorites, Ronny Jordan and Hiram Bullock, who otherwise would have been on my list. Even with that I still couldn't find room for Robert Johnson, or Mike Bloomfield, another one of my all time favorite guitarists. The list is not intended as a ranking, my selections are simply arranged according to the age each guitarist reached.

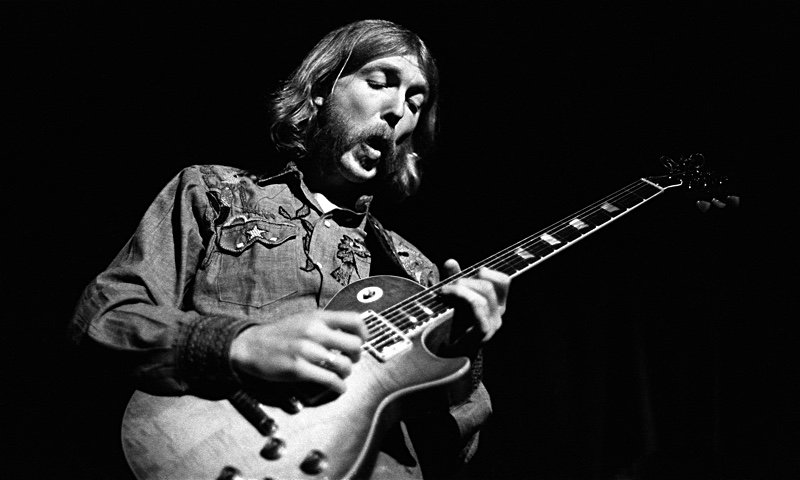

1. Duane Allman, age 24, died as the result of a motorcycle accident in 1971.

His early recordings from the period 1966—1968 with the Allman Joys and the Hour Glass weren't particularly noteworthy. It was in 1969 as a session player in Muscle Shoals, Alabama that the unique talent of Duane Allman began to emerge. His recordings with Wilson Pickett, Boz Scaggs, King Curtis, Aretha Franklin, Clarence Carter and others captured the attention of recording stars and influential music insiders. This resulted in a label putting its trust and resources behind him, and giving him the freedom to form the Allman Brothers Band.In an age of preening and prancing rock musicians with super star egos, Duane Allman established a musical brotherhood where the first commandment was to serve the music. Stand and deliver—with a workmanlike attitude and street clothes—that was the band's calling card. With them he recorded two studio albums, and At Fillmore East, a legendary double live album produced by Tom Dowd. Tragedy struck before the third studio album, Eat A Peach,was completed; as a result he only appears on three of its studio tracks. Fortunately there was a wealth of unused material from the live recordings at the Fillmore East, and Eat A Peach was released as a double album in order to include some of these treasures. These recordings, along with his collaborations with Eric Clapton represent a substantial share of a musical legacy he recorded in less than three years.

Not only did the band he founded survive over four decades after his death, but his influence and playing continue to inspire musicians and fans around the world. In terms of technical proficiency he might not have been the equal of some others on this list, but he was an extraordinary soloist. He had a unique and emotive musical soul, great sound and tone, and a fluid sense of time that took the audience on a spellbinding journey to other realms. Musically he was on fire during the final year of his life, remarking that his hands were finally catching up with his mind. He was a left-handed guitarist who played right-handed and revolutionized the sound and role of slide guitar in modern music—an innovator who left an indelible mark on the music world. Think back to the slide guitar prior to Duane Allman as you listen to this "Mountain Jam" solo.

2. Charlie Christian, age 25, died of tuberculosis in 1942 and was buried in an unmarked gave in Texas.

There have been a few inductees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame who seemed a bit of a stretch, but Charlie Christian certainly earned his spot. When you listen to Danny Cedrone's epic solo on "Rock Around the Clock" from way back in 1954, it sounds truly revolutionary. But if you then listen to a 1941 recording of Charlie Christian playing "Stompin' at the Savoy" at a small club thirteen years earlier, you begin to understand why he is such a towering figure among guitarists.His career took off in 1939 when Benny Goodman hired him for his sextet. He was a true pioneer of the modern electric guitar. Jimmy Smith would later liberate the Hammond B3 from big chord solos by emulating the approach of horn players, but long before him Charlie Christian had done the same with the electric guitar playing single note solos.

It is particularly striking how contemporary Charlie Christian's sound and approach remain. His sound was not the low treble, somewhat muffled sound which was widespread among jazz guitarists in the 50s and 60s. I recall listening intently to one of his solos, forgetting that he was playing with Benny Goodman. It seemed so fresh, energetic, and lively, without a hint of nostalgia, and suddenly when the clarinet resurfaced it underscored just how revolutionary he was.

In a few brief years, without the opportunity to record professionally as a band leader, he made a tremendous impact on modern music and redefined the role of the electric guitar. Had his light not been extinguished so early, imagine how different the music we listen to today might be. Imagine if he had lived long enough collaborate with Charlie Parker or Miles Davis. Come to think of it, he would have only been in his early 50s when Jimi Hendrix made his American debut at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967—Christian would have been seventeen years younger than Carlos Santana is today. With any luck, there will be a poster on the entrance of the pearly gates announcing a Charlie Christian concert.

3. Jimi Hendrix, age 27, died in London in 1970 of asphyxia related to an overdose of barbiturates.

The artist known as Jimi Hendrix was active from 1966 until his death in 1970. Prior to that time he worked often under the name Jimmy James as a session guitarist and supporting musician for several R&B acts. He was an electrifying performer who understood the power of showmanship, but he was also a uniquely gifted guitarist, a cutting edge audio innovator, and a perfectionist and wizard in the studio.What's left to share about Jimi Hendrix, one of the most iconic rock musicians who ever lived? Perhaps some jazz lovers aren't aware that Jimi Hendrix and Miles Davis jammed together on a few occasions at Davis' apartment, and had planned to record together. But it gets even more interesting. At the Hard Rock Cafe in Prague there is a telegram on display from Jimi Hendrix to Paul McCartney, sent to Apple Records on October 21, 1969 which reads:

"We are recording an LP together this weekend in NewYork. How about coming in to play bass. call Alvan Douglas 212-5812212. Peace Jimi Hendrix Miles Davis Tony Williams." It's doubtful that McCartney received the telegram as he was on vacation, but talk about a super-group.

Miles Davis also wrote in his memoir that at the time of Hendrix's death, he and Gil Evans were in Europe planning a recording session with Hendrix. The mind reels at what might have been.

Here is Jimi Hendrix's cover of Bob Dylan's "All Along the Watchtower"—an extraordinary achievement. Hendrix spent six months overdubbing and substituting tracks trying to get the perfect sound. Proving that necessity is the mother of invention, after trying everything in sight, he used to lighter to get the slide sound he was hearing in his head. The web has a wealth of information and audio outtakes from this song, but be warned, you may get lost in a cyber rabbit hole.

4. Magic Sam, age 32, died of a heart attack in 1969 in Chicago.

Like many bluesmen before him, Sam Maghett, who performed as "Magic Sam," left his home in Grenada, Mississippi for Chicago, Illinois. He was only 19 years old when he arrived in Chicago in 1956. Soon thereafter he was signed by Corba Records. A brief stint in the army and a six month prison sentence for desertion interrupted his musical career. By 1963 he had a single that was getting play, and he was touring in the US and Europe. Eventually he signed with the Delmark label and recorded an album in 1967 and another in 1968. Despite more than a decade of paying his dues, Sam did not really break out—at least not in a way that matched to his talent.Talent is important to success, but it also requires is a certain degree of serendipity. There is a Zeitgeist, or a cultural climate of an era, and to be successful your talent and artistic voice need to be in sync with it. In rare cases, an artist or group of artists influence the Zeitgeist. The Beatles are an obvious example. Nonetheless, there is more to it than talent and a confluence of the right people being at the right place at the right time. The Beatles were famously turned down by several labels before George Martin took them on. What if Columbia or Phillips had signed them, stripped them of their originality, and there had been no George Martin producing them? Or what about the Beatles without Brian Epstein, would they even have gotten a contract in the first place?

In any case, in 1969 Magic Sam was at the right place at the right time. That year he appeared at the first Ann Arbor Blues Festival with many of the biggest stars on the blues scene: B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Otis Rush, Magic Sam, Freddie King, T-Bone Walker, Lightnin' Hopkins, and Big Mama Thorton—and bookers took notice. On YouTube you can find some of his live club recordings from 1969. To my ears he sounds like he was perfectly in sync with the spirit of the times. His career was ready for take off, but tragically he died on December 1, 1969.

5. Stevie Ray Vaughan, age 35, died in a helicopter crash in 1990 in Wisconsin.

Stevie Ray Vaughan was a witches brew of talent, creativity, intensity, and showmanship. He also had a gift of being able to internalize the essence of other great artists without copying them. For example, you can clearly hear the influence of Albert King and Jimi Hendrix in his playing, but at the same time he was unmistakably Stevie Ray Vaughan, and in that there is genius.There were few who could take the stage with Jimi Hendrix or follow him on stage. In a BBC documentary Jack Bruce recalled when Hendrix audaciously asked to sit in with Cream during a London concert and blew Eric Clapton out of the water. Bruce said Eric was a great guitarist, but Hendrix was a force of nature. In his biography Clapton essentially confirms the story, and states that he, along with the audience, was gobsmacked by Hendrix. Had Hendrix been alive in the 80s, it seems likely to me that Stevie Ray Vaughan would have tried to sit in with him.

How might that have gone? Opinions are like, um, navels, everybody's got one—here's mine. As a teenager I had a chance to see Hendrix live. This was in March of 1968 at the Hilton Hotel Ballroom in Washington, D.C. It was a time of youth rebellion and anti-war protest, and there was palpable tension in the air. Because of this there was a sizable number of uniformed police in the ballroom. What you don't get from film of Hendrix is how loud he was—it was provocatively loud. He was generating feedback and doing all kinds of overtly sexual antics with his guitar as the deafening feedback wailed and the low tones rattled your bones and vibrated your internal organs. He went to the microphone and dedicated a song to the boys in the penguin suits, i.e. the police. I remember thinking, "they're going to shut this down." It was dangerous, outrageous, provocative, and unforgettable—an incredible spectacle that film couldn't truly capture.

Musically? Here is where it gets interesting for me. There are those magical moments when you see an artist completely in the moment, transfixed like he or she is channeling something from a higher place, and time slows down as it does right before a traffic accident. There is an intensity, it's magical, and it is all about the music—seeing Duane Allman was like that for me. I didn't experience that with Hendrix, nor have I seen any live footage on YouTube to suggest it. He was a tremendous guitarist and showman, but for me his magic happened in the recording studio—there he was perhaps unmatched in his genius.

Stevie Ray Vaughan was also a master showman. He was flamboyant with a toolbox full of tricks and monster licks, but at the same time he was also intensely into the music. YouTube is replete with examples. Yet I don't think he would have tried to shut Hendrix down. I suspect he would have shown Jimi Hendrix the same respect that he showed Albert King, but he would have motivated Jimi Hendrix to bring his A game. There is a fascinating YouTube clip of B.B. King playing "Texas Flood" with Stevie Ray Vaughan, and it is B.B. King like you've never seen him before. Stevie Ray Vaughan on stage with Jimi Hendrix, that's a fun daydream!

Interestingly, Jerry Wexler, who was so influential in Duane Allman's career, also played a pivotal role in Stevie Ray Vaughan's career. Wexler convinced Claude Nobs, organizer of the Montreux Jazz Festival, to book Stevie Ray for the festival's blues night, calling him, "a jewel, one of those rarities who comes along once in a lifetime." From there his career took off. The legendary John Hammond who scouted Charlie Christian and recommended him to Benny Goodman, recommended Vaughan to Epic Records who signed him in early 1983. A year later when he played Carnegie Hall, Hammond introduced him as, "one of the greatest guitar players of all time." Indeed.

Here is a clip of him playing with the late-great Hiram Bullock, Don Alias, Philippe Saisse, Tom Barney, and Omar Hakim.

6. Shawn Lane, age 40, died in 2003 after decades of debilitating illness and pain.

At the age of 14 he joined the group Black Oak Arkansas as lead guitarist (search YouTube for them in 1979.) Visually a fly is capable of tracking movement five times faster than a human, and yet I suspect that even a fly could not track Shawn Lane's guitar playing. The word unbelievable is a truly apt description of his playing. I highly recommend a Q&A on YouTube in which he talks about speed. He is associated with speed, but that was only one facet of what he was about. He had a highly developed musical mind and a thorough understanding of music theory and technique. He was a virtuoso on both guitar and piano.It seems impossible, but after his first solo album was released in 1992, Guitar Player Magazine named him "Best New Talent," and Keyboard Magazine named him to the second spot in the category "Best Keyboard Player." As a teenager he was influenced by Allan Holdsworth and drawn to a progressive fusion style of music. He was also profoundly influenced by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, a renowed Pakistani singer of Qawwali, the devotional music of the Sufis—a name many Derek Trucks fans will recognize. In fact, I learned in an interview with drummer Jeff Sipe who worked with Shawn Lane in the group Hellborg, Lane, Sipe, that Jeff was the person who turned young Derek on to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan when they were touring together in a van.

Despite unrelenting joint pain and the swelling and weight gain caused by hydrocortisone, Shawn Lane made music for thirty years. He was truly an exceptional musician. My favorite clip is from 2001 as he was playing a guitar solo with a group of Indian musicians, which included the late great U. Shrinivas who also left us too early.

7. Jeff Healey, age 41, died of cancer in Toronto, Canada in 2008.

Jeff Healey's eyes were surgically removed when he was one year old due to a rare form of cancer. At the age of three he was given a guitar, which, because of his size, he found easier to play on his lap. At a school for the blind he was taught the conventional approach to guitar, but did not switch. His technique gave him a different approach to string bending and vibrato. Chet Atkins was an early influence, but he was drawn to blues rock with an emphasis on power and intensity. He was also a very capable vocalist.But there was another side to Jeff Healey. In high school he divided his time between his rock band and playing trumpet in his high school band. According to his obituary in the New York Times he also played clarinet. He had an intense attraction to the traditional jazz music of the 20s and 30s and amassed a 78rpm collection of over 30,000 records. Such was his love of this music that he hosted a radio program on which he shared favorites from his collection.

His career really took off with the release of See The Light in 1988, and his acting and musical performance in the movie Road House starring Patrick Swayze.

In the new millennium Jeff Healey formed his own jazz band which played the traditional jazz he so loved. He played some guitar in this formation, but he was primarily on trumpet and vocals. You can get lost on YouTube watching video clips of Jeff Healey, on guitar and trumpet.

Here is a must-see clip of Jeff Healey with Dr. John, Marcus Miller, and Ormar Hakim.

8. Lenny Breau, age 43, was murdered by strangulation in 1984 in Los Angeles, California. The case is still unsolved.

Like Shawn Lane, Lenny Breau was an artist I discovered fairly recently. One day on YouTube I happened to come across Lenny Breau and it literally shocked me that I could have been unaware of him for decades. At this time I had the opportunity to interview a group of three musicians who are themselves guitarist's guitarist: Jimmy Herring, Michael Landau, and Wayne Krantz. So I used that opportunity to ask them about Lenny Breau, and this confirmed that I had already learned—musicians are themselves some of the world's greatest music fans. I discovered that our own John Kelman had actually been introduced to Lenny Breau by his guitar teacher at a club in Canada, so I also interviewed him about it.Rather than trying to reinvent the wheel, I would encourage readers who are interested in Lenny Breau to go to his website, lennybreau.com and read an appreciation by Jim Ferguson written in 1984, the year of Lenny's death. It is a wonderful biographical sketch and insight into his extraordinary technique.

His parent were French Canadian, professional country western musicians, with whom young Lenny toured and performed. Initially Chet Atkins was a major influence, but he was drawn to jazz. He struck out on his own at the age of 18 after his father slapped his face for playing jazz riffs on stage during a performance. Later he also developed a fascination with flamenco guitar and Indian music. He developed a technique for playing previously unimaginable harmonics, and had the mind boggling ability to play bass lines, chords, and solo notes all at the same time—an absolute genius. From everything I've learned he seems to have been a beautiful and tragic soul, who had difficulty coping with the demands and pressures of a solo career.

His daughter, Emily Hughes, produced an insightful documentary entitled, The Genius of Lenny Breau which was released in 1999. It has been expanded and re-edited, but doesn't seem to have been released yet. Here is the trailer:

9. Django Reinhardt, age 43, died in 1953 in Paris of a cerebral hemorrhage.

It's surprising his life hasn't been the subject of an Oscar worthy film, or better yet, an HBO mini-series. If it were written as an original story, it would surely be rejected as implausible.No doubt many of us have used the term gypsy without realizing that it is offensive to many Romani people. Although born in Belgium, Django Reinhardt's parents were French and of Romani descent. By the age of fifteen he was married and able to make a living playing music. Soon thereafter tragedy struck. Returning home to his caravan after a performance he knocked over a candle. In the resulting fire he was badly burned, and lost the use of two of his fingers. Doctors wanted to amputate his right leg, but thankfully he refused the surgery, and despite their dire prognosis he was able to walk again within a year with the aid of a cane. This would have ended the musical career of most musicians, but as we all know, Django Reinhardt with only two fingers was able to secure a place in that pantheon of guitarists who are considered the greatest who ever lived. Jeff Beck has referred to him as superhuman.

At the start of WWII he was in London. His partner, violinist Stéphane Grappelli, remained there, but Reinhardt quickly returned to France. As most of us know, the Nazis waged a propaganda war against jazz. They despised it as music that was often written by Jews and played by blacks. It was not a good time to be a jazz musician in Nazi occupied territory, but on the surface at least, Django faced an even greater threat. In Germany Romani people were being sent to concentration camps. In France, Belgian Romani people who lived in caravans were being deported to Belgium and from there sent to concentration camps. As strange as it may seem, throughout the Nazi occupation of France, Django enjoyed an unrivaled level of success. He amassed a fortune with hit records and was even able to tour other countries under Nazi control, at a time when his people were being exterminated. There is a fascinating documentary on YouTube that deals with how he was able to do this.

Rather than trying to write something about someone whose talent I can't begin to understand, I'll share something I came across—from Dave Gould's excellent website dedicated to Django Reinhardt. This is a a short except from a lengthly 1976 interview with his partner, Stéphane Grappelli, I found there:

"People often ask me if Django practised. Oh no, not Django; he was born with that technique. In my opinion we can compare him with that other phenomenon Paganini. By the music he left behind one can tell that Paganini must have been a fantastic player. I think Django was about the same degree a phenomenon. I remember one day he really let me down, I didn't know where he was and when he came back four months later, he assured me he hadn't touched the guitar—he'd lost it. That same night he played like a God. I had never heard anybody play the guitar like that; and after four months inactivity. I said, 'How can you do it? If I stop playing the violin for one week I can't play.' 'Oh, I don't know,' he said. He never knew, it was always 'I don't know.' Anyway, he was so pleased to get back to his guitar and he was so amazed at his re-awakening that he didn't stop playing all that night. But of course his fingers were injured and they were bleeding. He'd go running up those very sharp strings so fast that he hurt himself, but he didn't take any notice. He used to play the guitar with the fingers sometimes, instead of the plectrum, and he liked the Spanish guitar. I remember us being invited to a party by a titled lady who used to delight in giving parties and inviting among her guests two people who were absolutely the opposite both in conception and tastes. This particular evening it was the turn of Andres Segovia and Django Reinhardt. So of course Django arrived three hours late, and without a guitar. Segovia was there, naturally at the right time and he'd played his repertoire. Everybody was upset because of Django and finally he arrived with a lovely smile, thinking it was okay. We said, 'Where have you been ? You're three hours late.' 'Oh, I didn't know.' Because Django never knows the time. He goes by the sun. 'Django, now it's your turn to play something.' But of course he had forgotten his guitar and Segovia doesn't want to lend him his, so someone has to rush off in a taxi to find some old box somewhere. And there you are; Django played solo guitar with a plectrum and then his fingers and he produced such a fantastic sound and improvisations that Segovia was amazed and asked, 'Where can I get that music?' Django laughed and replied 'Nowhere, I've just composed it!'"

10. Wes Montgomery, age 45, died of a heart attack in Indianapolis, Indiana in 1968.

Wes Montgomery lived the longest of all the guitarists on this list, but he also had the latest start. He was completely self taught and didn't own a six string guitar until he was twenty years of age; although it should be noted that he began playing a four string tenor guitar at the age of twelve. His method of learning was the same as Charlie Christian's. Christian learned Lester Young's sax solos note for note until he had mastered them. Montgomery did the same thing, except he learned Christian's solos.His now legendary technique is, in part, the result of some lucky happenstance. There is a great DVD of a television appearance in Belgium and during the practice session with the local pickup band he complains about the difficulty of keeping a guitar in tune. This frustration with guitar tuning was also the spark that gave him the idea of playing melodies with octaves. He noticed his guitar seemed in tune with open strings, but as he moved up the neck it wasn't. So to test it he played octave notes on two strings and moved up and down the neck—then he recognized the possibility of playing melodies this way. Similarly, it was his desire to practice with an amp that led to his thumb technique. His family and the neighbors complained about his loud guitar, so to keep it quiet but still use an amp, he began to play with his thumb instead of a pick. The rest is history.

By the time he was twenty eight he was touring with Lionel Hampton, but the luster began to fade. He became disenchanted and after a couple of years he returned to his family and a day job in Indianapolis. After work, he would play evening gigs in clubs, and afterwards he had a regular slot at an after-hours club, the Missile Room. It must have been extremely hard to keep the dream alive. His wife didn't like what he played, and she warned him that people wouldn't buy music she wouldn't buy. She encouraged him to play blues, pretty music, or music people could dance to. There he was, 36 years old supporting a wife and more kids than he could fit comfortably in a car, working full time and trying to launch a musical career in Indianapolis.

His seemingly dead end Missile Room gig turned out to be his talisman. It was the place where touring musicians would hang after their own gigs were over, and gradually this exposure paid off. In 1959 Nate and Cannonball Adderley made a point of seeing him and were quick to act. They enthusiastically recommended him to Orrin Keepnews, the creative head of Riverside Records. He traveled to Indianapolis and after sitting at the bar in the Missile Room and watching Montgomery play, he pulled out a standard union contract and signed him on the spot.

Keepnews quickly arranged for Wes Montgomery, and his group from the Missile Room (organist Melvin Rhyne, and drummer Paul Parker) to come to New York City to record an album. The album, The Wes Montgomery Trio, essentially captures the music they were playing after-hours at the Missile Room.

Despite artists such as Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, and Wes Montgomery, Riverside Records filed for bankruptcy in the summer of 1964. Montgomery was now famous in jazz circles, and well received by critics, but his records weren't selling well and he wasn't making money. The demise of Riverside Records closed one door and Creed Taylor opened another.

Some see Creed Taylor as a corrupting influence who was responsible for Wes Montgomery selling out and abandoning true jazz. I'm not in that camp, but I am admittedly biased because of the pivotal role he played in the music that turned me on to jazz: Bossa Nova, Stan Getz, Herbie Mann, Jimmy Smith, and Wes Montgomery.

In 1964 the Beatles had turned the music industry upside down, and Creed Taylor was someone who understood that jazz labels needed to adapt to a new situation. In 1964 Wes Montgomery was 41 years of age and had struggled for 21 years as a jazz musician. He had a wife and seven children to support, and without his day job his financial situation was bleak. In 1968 he told the Associated Press: "My direction before was hard jazz. But it began to dawn on me that I might understand what I'm doing, but if I can't project to the point where I can communicate, it doesn't mean anything. Since everybody has to survive, economics forced musicians out of jazz. And what is playing music for anyway? People to enjoy themselves. That is my direction now."

Thanks to Creed Taylor, Wes Montgomery finally achieved commercial success, he was all over the radio, he had a Grammy and multiple nominations, a greatly expanded fan base, and a level of recognition commensurate with his talent. There were some pop song covers that worked, and unfortunately some that can best be described as cheesy, but even on the most commercial albums there were some treasures. Moreover, Creed Taylor also produced Smokin' at the Half Note, an absolutely essential Wes Montgomery album, and gems like Jimmy & Wes: The Dynamic Duo, and Further Adventures of Jimmy and Wes. With the benefit of hindsight, it would have been wonderful if Creed Taylor had made arrangements to have Wes Montgomery's concerts recorded during the time they switched directions for his studio releases. From accounts, when playing live Wes Montgomery was still very much into jazz, and still smokin.' But who could have imagined that he would die so young?

So that's my top ten list of guitarist who left us too soon. Each great in his own way, and amazingly Charlie Christian, Django Reinhardt, Jimi Hendrix, and Wes Montgomery, arguably the four most influential guitarist in the modern age, are all on this list. Who was the most influential? Personally I'd say that they are the four corner posts of a foundation upon which the best of modern guitar playing rests.

I've clearly passed over many other worthy guitarists, and hopefully the comment section will extend this list to pay tribute others guitarists who didn't reach the age of fifty.

Tags

Jimi Hendrix

Top Ten List

Alan Bryson

Ronny Jordan

Hiram Bullock

Mike Bloomfield

Duane Allman

Boz Scaggs

Charlie Christian

Benny Goodman

Jimmy Smith

Charlie Parker

Miles Davis

Carlos Santana

Paul McCartney

Tony Williams

Gil Evans

Chicago

B.B. King

Muddy Waters

Howlin' Wolf

Stevie Ray Vaughan

Jack Bruce

Don Alias

Omar Hakim

Allan Holdsworth

Derek Trucks

Jeff Sipe

Chet Atkins

Jeff Healey

Dr. John

Marcus Miller

Lenny Breau

Jimmy Herring

Michael Landau

Wayne Krantz

Django Reinhardt

jeff beck

Wes Montgomery

Lester Young

Lionel Hampton

Cannonball Adderley

New York City

Bill Evans

Creed Taylor

Stan Getz

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.