Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Tom Lawton: Not Less Than Everything

Tom Lawton: Not Less Than Everything

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea.

Quick now, here, now, always—

A condition of complete simplicity

(Costing not less than everything)

—T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets; "Little Gidding"

This poetic quotation captures the essence of pianist Tom Lawton. He is a musician who is listening "in the stillness" to serve the whole group, and he always lends his own ideas to the occasion "between two waves of the sea," with remarkable, imaginative, solos. He has given "not less than everything" to the music, often running non-stop for weeks on end, and at every gig being "quick now, here, now, always" as if it were the most important moment. When he plays, ears perk up to the sensitive artistry he brings to any performance.

Lawton is a Philadelphia-based jazz pianist who has for several decades had a non-stop career playing countless club and concert gigs, composing and directing memorable ensemble pieces, appearing on numerous recordings, and associating with some of the best musicians in the business, including clarinetist Don Byron, saxophonists Bootsie Barnes, Larry McKenna, Bobby Zankel, Ben Schachter, and Odean Pope, drummer Dan Monaghan, bassist Lee Smith, trumpeter John Swana, vocalists Mary Ellen Desmond, Joanna Pascale, and Jackie Ryan, and many others too numerous to mention. In addition to his regular jazz gigs, he performs at parties and social gatherings where the host wants a musical artist of high caliber, and this includes the social events of some of the best musicians in the world, the Philadelphia Orchestra. He is a sought-after teacher, privately and on the jazz faculty of the University of the Arts, Temple, and Bucks County Community College. In all that he does, he carries the badge of his own remarkable teachers, Gerald Price and Bernard Peiffer [pron. Pay- fair -Eds.]

Another way that Lawton manifests the phrase "not less than everything" is the range of his playing and composing. His music encompasses everything from the creole jazz of Sidney Bechet, to the swing era, bebop, hard bop, and the avant-garde. He is immersed in classical composers from Bach to Bartok to Messiaen and Ligeti, and you never know when one of them is going to show up in his playing. He is the quintessence of one who has "big ears," the musicians' term for someone who can hear and play without boundaries or adherence to a particular school or style. His quintessential recording, Retrospective Debut (Dreambox Media, 2004) provides a showcase of all original compositions reflecting many of these diverse influences.

The coronavirus pandemic has kept musicians from live performances, but Lawton is quite busy teaching online these days. All About Jazz caught up with him via Zoom at his home in Montgomery County. A Zoom video of the interview is available privately. The transcription below has been edited from the original.

All About Jazz: First of all, we're in the midst of the COVIDS pandemic with all its restrictions, and it has profoundly affected the musicians because you can't play in concert halls and clubs. This is a tough time for you guys. So how is it going for you, and what's happening with the other musicians you know?

Tom Lawton: For the most part, none of us are playing live gigs. Personally, I'm not in a hurry to get back to it, because I wouldn't trust that it would really be safe rather than spark a resurgence of the virus and having to close again. I've become one with the idea of not doing it for the time being.

AAJ: Don't you miss the feeling of being in the rooms with your groups in front of an audience?

TL: Oh, of course, I miss it! But I don't focus on it. I've embraced my current activities, mainly teaching online and composing. In some ways, I'm busier than I've often been in the summer months. Not all of us are that lucky, but I have a larger private teaching load now than I normally would this time of year.

AAJ: That's great. So, to get into the music, and for a warmup, let's start with the infamous desert island question. What recordings would you take with you if you could only take a few?

TL: You asked that in the first interview I did with you about fifteen years ago! While I'm thinking about that, there's something I've always wanted to clarify for anyone who read that first interview. When I said I never wanted to do the historical thing, it may have sounded like I was putting down the music of the past. But what I meant was that I had trouble with the idea of jazz as a repertory music of historical vintage. That said, at this point, I now think that even that has its place in the pantheon, even though it's not my chosen path. Of course, I deeply respect the history, and often delve into it, and believe that it's necessary. I often write referencing it, just not setting out to be "officially authentic." I just wanted to clarify that because some people misunderstood what I said.

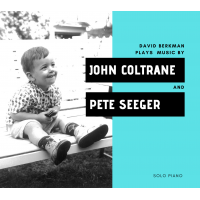

Getting back to the desert island question, a couple of the records would probably be the same as then. The first would be the thing that converted me into a jazz musician: The John Coltrane Quartet Plays: Chim Chim Cheree, Song of Praise, Nature Boy, Brazilia (Impulse! 1965). The track that inspired me to be a jazz musician was "Brazilia." And I'd also probably take one of the early Dave Douglas Tiny Bell Trio recordings (The Tiny Bell Trio, Songlines, 1994). Michael Formanek's Low Profile (Enja Records, 1994). Probably Wayne Shorter's The Soothsayer (Blue Note, 1979).

AAJ: What is it about Dave Douglas that grabs you?

TL: I met Dave in 1993 when I was in Europe with Don Byron the clarinetist, and I've been listening to him ever since. Dave Douglas was a sideman in Byron's group, and he had just released his first Tiny Bell Trio record. Before that, I never heard of him, but when I listened to him, I felt he had the whole package, and ever since then, I've felt the same way. With all his recordings and all his different groups, he always has the total package of his compositional ideas, how he lends his writing to whatever group of improvisers are surrounding him at the moment. Add to that his extremely personal sound on the trumpet, an individual voice on his instrument, his writing, and his approach to band leading. I have no idea how he has the ability to keep his unique voice with so many different groups and adapt his writing to the strengths of each group.

Coming Up: The Transition from Classical to Jazz Piano

AAJ: You mentioned Coltrane's "Brazilia" as a life changing experience for you. It's a beautiful piece, but what affected you so deeply about it?TL: I heard it a year or two after I graduated from high school, and I was dabbling in jazz a bit. But it was the exotic sound of McCoy Tyner's harmony that got me. He had the fourths, but he also had the mixed exotic superimposed dominant sounds. And the way Trane was playing over that. And Elvin Jones's volcanic propulsion underneath. The whole package was unlike anything I'd ever heard before! To this day, I frequently return to that recording, and I'm still amazed. It always has the same effect, as if I'm listening to it for the first time.

AAJ: It's remarkable how one musical experience can have such a lasting impact. Other musicians I've interviewed have similar moments when they heard a recording and it inspired them to a career in jazz or to new heights of composing and improvising. By way of background, I believe you started out as a classical pianist. When did your jazz career begin?

TL: All through high school I studied classical piano, but I always improvised both classical music and in some rock bands. When I got into jazz, I was already getting into improvising, but I wasn't accustomed to the idiomatic jazz approach, and that took a while to learn.

AAJ: How did you begin to immerse yourself in the jazz idiom? Did you have a teacher?

TL: Well, first of all, I heard a lot of jazz growing up. My father had a collection of mostly big bands like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Benny Goodman. I always enjoyed it, and he also had some of Thelonious Monk. I always loved hearing it, but it never occurred to me to play it. That said, once out of high school, I got my first gig out in the sticks in Schwenksville, PA, and I got twenty-five bucks to play on a Sunday afternoon from 2 pm to midnight! It was a solo gig. I only knew two tunes: "Misty" and "Moonlight Serenade," and the rest of the time I improvised in the manner of composers like Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff.

AAJ: Didn't you have a fake book, or what they now call a real book, with all the pop and jazz tunes?

TL: I didn't even know about that! Then, a couple of weeks into the gig, the owners took me aside, and said, "You gotta learn some tunes!" [Laughter.] They suggested I come in on a Friday or Saturday to hear this guy Gerald Price with his trio.

Learning from Gerald Price

AAJ: Gerald Price! He was a top shelf pianist of the time who worked with so many of the greats.TL: There he was in Schwenksville with Benny Nelson on bass and Al Jackson on drums. And it was right around the time I heard the Coltrane "Brazilia." I was really transfixed by these guys and the impression they made on me: their rhythmic feel, great harmonies, the group interplay, and you could tell they were having fun. I went a couple of more times, and then I asked Gerald if he taught. He accepted me as a student, and I went down to West Philly where he lived.

He was very illuminating. He talked about needing to know tunes, the repertoire. He had a very informal way of teaching. He'd be going through a tune like "My Romance," and he'd suddenly stop and say, "Did you hear the E flat seventh here?" And he'd show me various options for getting from point A to point B in a couple of bars. So that part was harmonic, but he also had a great sense of swing, which he never mentioned, but I picked up very easily by ear. None of my jazz teachers ever suggested getting a book to study. But he was the one who told me to get a fake book for my gigs, and also suggested learning tunes from recordings.

AAJ: Did Gerald Price teach you any particular jazz style or approach to the piano?

TL: For me, Price was basically dealing with harmony, ways of voicing chords and using substitute harmonies. He was a master of all the straight-ahead chord substitutions. There was a whole vocabulary that bass players were supposed to be able to hear instantly on jobs. That, unfortunately, is becoming a lost art today. People are relying too much on books now, so they know only one version rather than the whole gamut. Piano players vary in the kinds of chords they play, and a good bassist needs to be very quick to hear and adapt to the particular substitutions.

Taught and Inspired by Bernard Peiffer

AAJ: It sounds as if you got a solid grounding in jazz with Price. Now, somewhere along the way after that, you came in contact with, in my opinion, one of the most amazing pianists, teachers, and personalities in the history of jazz, Bernard Peiffer. Peiffer mentored some of the finest jazz pianists of your generation like yourself, Uri Caine, Don Glanden, and Sumi Tanooka. Before that, he rose to stardom in the jazz scene in Paris, playing with Django Reinhardt, leading his own quintet, composing film soundtracks, and achieving notice in the clubs of Paris, Monte Carlo and Nice, and eventually becoming nationally renowned. He moved to Philadelphia in 1954 I believe, with his wife Corine and daughter Rebecca. He made a few recordings for major labels, hit top spots like the Newport Jazz Festival, but then just about vanished from the national scene, taking up a life of teaching and occasional playing in the Philadelphia area. Who was this masked man? Tell us about him.TL: He's an unusual figure because although he made some great recordings, his very best playing was never recorded. I heard an amazing recording of him at a friend's house in high school. I forgot about it, went on, studied with Price, and got to a point where I was doing a lot of gigs. Then a friend of mine got in touch with the pianist Bob Cohen who asked me to come to his house and play for him, and when he heard me he said, "Your playing reminds me of Bernard Peiffer. I really think you could benefit from studying with him." In addition to putting me in touch with Peiffer, I would say my life changed through Bob Cohen. I met my wife Fran through him! She knew him, and he sent her to hear me.

On Bob's suggestion, I called Bernard. that was in 1974, and I studied with him regularly through the last two years of his life. As far as his teaching method is concerned, each of us who studied with him has a different story about it. For me, he didn't use any method at all. At my first lesson with him, I was overwhelmed because he asked me to play something, and I was only a year or less into jazz. He made a bunch of points, ticking them off on his fingers one by one. The first thing he said, almost scolding, was "You do not use enough bi-tonality" [the use of more than one key simultaneously.—Eds.]. Then he talked about the shapes of lines, the contours, some comments about rhythm and dynamics. His favorite phrase was, "You need to take it into a different dimension." For me, all that was overwhelming, because I didn't even know how to do basic bebop at the time.

Most of what Peiffer gave me, I couldn't make use of at the time. It took until five years or so after he passed for me to get it. Still it was very valuable at the time. For most of us who studied with him, it wasn't so much what he taught as it was just hearing him play. It was hearing him demonstrate stuff and hearing his musical philosophy that changed me. It wasn't so much the assignments and what I practiced for him. I'd bring in something and we'd discuss it. Or he'd bring up things like Hindemith's third sonata, Prokofiev's third piano concerto, and I'd learn to play them—that was formalized to a degree.

The jazz stuff was just very high-level artistic coaching. He would say something like, "You need to make that introduction sound more introductory." And he often expressed that an artist is always wrestling between two things: continuity and contrast. Which is more relevant at any given moment? He worded it a little bit differently, but I'm always using that idea when I write or play. And if it is contrasted, for example, is it meant to be sudden and surprising or is it meant to flow out of what came before? That's the kind of teaching I got from him. Other students have told me that he made them do a lot of scales and modes in very formalized ways, but he never asked me to do that.

AAJ: He seemed to take you to the heart of the music. The things you mentioned are so much what makes music flowing and meaningful.

TL: Yes, he taught me the universals of any kind of music. But it took me a few years to really incorporate it into my playing. Before that, I had to learn more of the basics, like bebop, and the guy who gave me the best pedagogy on that was the bassist, Al Stauffer.

AAJ: Before we get to Al, I just want to say to readers: "Get to know Bernard Peiffer!" He was an amazing musician, and his life story is so moving. He went through World War II in France, worked with Django Rheinhardt, became a member of the French Resistance, and in Philadelphia, he mentored some of the greatest pianists. He had a tragedy in his family—his youngest daughter died and he wrote a memorable song about it called "Poem for a Lonely Child." And so on. His story and music would make a fabulous motion picture. To any serious jazz fan, I'd say you must get to know him and his music. He really is a legendary figure, but for various reasons, when he came to the U.S. after making a big splash and a few great recordings, he vanished into relative obscurity.

So, let's get back to Al Stauffer. One of my most wonderful memories was spending time with you and Al when you had that duo gig and you were the house pianist at the Four Seasons Hotel, one of most magnificent hotels at the time. Just relaxing in that beautiful lounge and listening to you and Al playing is etched in my memory forever. And he would take me aside during breaks and tell me story after story about his experiences with some of the jazz greats. He was a kind and gentle man with a generous spirit. So please tell us more about Al.

TL: OK, but first I want to say one more thing about Bernard. He was well known in certain circles for his astonishing technique. But I always found that much more than that, he was the perfect example of someone who had amazing technique, but he also had musical integrity that you could always feel, that was similar to Art Tatum. For them, their astonishing technique was always the means to the removal of all barriers to expression. A lot of people heard the technique, but they missed the depth of the music.

AAJ: I think Leonard Feather compared Peiffer to Art Tatum.

On the Job with Al Stauffer, Larry McKenna, Bootsie Barnes, and Odean Pope

TL: To get back to Al, in addition to being a great bassist, he taught improvisation to musicians of all instruments in Philadelphia. I can think of maybe ten or twenty players in Philly who studied improv with him. For me, it was important, because he started at square one. I had a lot of gaps to fill in, and he helped me do that. But he helped me not only by teaching me the scales and chords, but how do you use all that, how do you shape certain notes into lines, how do you do tensions and releases, how do certain color notes sound when they're highlighted. What happens within a chord and when you transition to another chord? He gave me all the materials in a fairly straightforward way, and then to hear how it all works, I just listened to him play.I then had to learn to apply all that on the spot when I'd be called to a gig by a sophisticated player like Larry McKenna. So to pick up the language better, I spent nearly two years listening to almost nothing but Sonny Stitt, teaching myself his way of playing, which helped me learn the straight ahead bebop language. The combination of Al's teaching and the studies I did on my own gave me the foundation to keep expanding my learning as I went on.

AAJ: Did Al teach more by instruction or by example?

TL: He started out with instruction. But what really helped was that he showed me things that happened in a million tunes, and it made learning all the tunes much easier than having to learn each tune as a brand new thing.

AAJ: I remember how Stauffer could make the music flow. It just seemed to always be moving forward like a river. I have a wonderful duet recording the two of you made called Blue Alterations (High Definition Tape Transfers/ DTR Recordings, 1981). A beautiful recording that almost nobody knows about. The improvising just seems to evolve spontaneously in an endless flow.

TL: I believe that was my first recording. It was done by a small mail order company that produced mostly classical cassettes. We did two for them. On the other one, (Al Stauffer Trio: Illumination; High Definition Tape Transfers/ DTR Recordings, 1981), we added a jazz recorder player, Joel Levine, an unbelievable musician who later moved from Philly to Toronto.

AAJ: A few years later, from around 1986-1988, you and Stauffer had the regular gig at the Four Seasons. I remember John Swana coming in to jam with you. Who was the other trumpet who worked there?

TL: That was the late Sy Platt. And saxophonists like Larry McKenna or Ben Shachter would come over to the Four Seasons as well and play with us.

AAJ: You worked with all of them quite a bit at various venues. How does that happen that you form a particular bond with some musicians and work with them over many years as you each also go your own way developing your careers? This kind of bonding really makes for a lot of the highest level playing.

TL: I can tell you specifically how I hooked up with Larry McKenna. I first worked with him at a place called the News Stand at 15th and Market in 1975. For me, Larry and Bootsie Barnes represented the best of the bebop tradition. They knew all the tunes, they had instant ears. I never studied formally with Larry, but I quickly picked up what he was doing. I could infer the chord changes from the way he was playing his lines. Or sometimes, he'd just yell out a chord change, like a D minor seventh, and then after a chorus or two I sort of knew it. Through the years, I've ended up doing a lot of gigs with him as a leader. And then everyone wanted him on their jobs because he could play so effortlessly, so I'd often end up on stage with him with other leaders. And whenever I could, I'd hire him for my groups. That's how we got to work with each other so often. And in addition to Sonny Stitt's music and Stauffer's guidance, I would say that Larry was my "real time" bebop mentor.

AAJ: I think of Bootsie as the bebop player; Larry seems more to come from the swing tradition.

TL: Same language; different dialects. Swing and bebop overlap a lot and the two blend very often. To me, Larry is a quintessential bebop player.

AAJ: Larry came out of the big bands, like Woody Herman's.

TL: Larry describes himself as a bebop player. He can do swing, but when you hear his phrase endings and his double time licks, it's bebop. Bootsie had a harder edge sound than Larry, and Bootsie dabbled more than Larry in Coltrane and a little bit beyond. To me comparing Larry and Bootsie is like comparing pianists Wynton Kelly and Red Garland: same language, different dialect.

AAJ: However you define his style, there's no question that Larry is a magnificent player. His sound and his improvisations are beautifully configured at a very high level. But getting back to you, I'm always amazed at the range of your playing and your resilience. You can go from the extremes of the avant-garde to all varieties and players of straight ahead mainstream, and step up to any of them. And your composing has all kinds of special touches. For example, your Man Ray Suite brings together a wide range of jazz idioms. Tell us a bit about how you bring all these different forces together into a whole. And the influences you get from both the classical and jazz sides.

TL: First of all, I learned that if you're hired as a sideman, you have to be selfless and contribute to the whole. I have to adjust to the idiom of the band and support the vision of the leader. Whatever gig I'm on at the moment is the only idiom, it's the only gig in the world to me. That said, my interest in a wide variety of styles goes back to when I blew my first paycheck on a whole variety of jazz records. I didn't know what I was buying! I got some straight-ahead Oscar Peterson and Red Garland, some older and more recent Miles Davis records, and late Coltrane like Meditations (Impulse! 1966), Cecil Taylor's Conquistador (Blue Note, 1966), and so on. I listened to all that stuff, and somehow to me, it's all one music.

Bobby Zankel and the Avant-Garde

TL: The interesting thing about the avant-garde musicians is their diversity: each of them has his own language. I played often with Bobby Zankel and the Warriors of the Wonderful Sound. Bobby has his own language. When I play with him, I can use my own language to some extent, but some of my things might not work with his aesthetic. So avant-garde is not all of one stripe. If anything, it's even more individualized than mainstream. I can compare my experience with Bobby with my work with Odean Pope, who straddles the line between bebop and avante garde and is adept at both. Both Bobby and Odean use a lot of fourth harmonies. I use a lot of those harmonies when I work with either of them. But I try to find different ways to use it. I want to be true to the person's aesthetic but without sounding like a total chameleon without any original ideas. I will say that I have been super-inspired by both of them.AAJ: Bobby Zankel was mentored by Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman and others. He told me that they and he are constantly shifting the tonal centers in their improvising, that is, there is not one key signature they follow or modulate between. So how do you follow along with that kind of playing?

TL: Yes. There's not a recurring form based on a recurring chord progression. And the harmony tends to be less what we would call functional. I hear a lot of Ornette in Bobby because of their amazing melodic sense and the "out" sound of their alto saxophones. Bobby's harmonies are fourth chords and modal, yet the melodic lines are similar to bebop. And I would just follow along with that, but sometimes there's more freedom, like some kind of flourish or fermata, and I'm just hearing musical gestures that lead into each other. They're not based on a chord progression, just musical utterances so to speak.

AAJ: I'm amazed that when I listen to the Warriors big band, it feels like there are no set rules, and everyone is going his own way, yet how musical and coherent it all becomes. It's hard to grasp what holds it all together so well.

TL: There's no formula, but there's usually a form. The tunes Bobby wrote for the Warriors had a definite form, and then as band leader he'd provide times when he'd open it up so it could be freer. Once, with David Murray, Bobby gave me a one-and-a-half minute solo intro. I didn't have a concept for it, I just let it come out. Something like that might just be a mood: atmospheric or aggressive. Sometimes the leader will just describe a mood and ask you to play it.

Modern Classical Influences

AAJ: It's striking to me that historically, the freer, less structured kinds of jazz came in at a time when modern innovations in classical music were also being absorbed, from Schoenberg, Debussy, and Ravel to Stravinsky, Bartok, Eliot Carter, even Stockhausen. Do you think there is a connection between those classical composers and the development of the avant-garde?TL: Sure! The harmony part of jazz has always come from European and classical music. It has been the melodic and rhythmic things that make jazz unique. Most of the harmonies are not unique to jazz. Jazz players even going back to Duke Ellington were always talking about how they were influenced by the impressionist composers. Herbie Hancock was very influenced by Ravel. For me, going on from that, I would have to say that harmonically in the music I compose, Prokofiev, Bartok, and Messiaen are big influences on me. For me, when I adapt these influences to jazz, it would be the rhythmic context that makes it new and different. For example, there are a lot of times when I need to integrate the non-western influences, the African, African American, and so on in order to give my music life.

AAJ: I know that Bartok had a great influence on modern jazz musicians. I never heard anyone mention Messiaen before now.

TL: I got into Messiaen around thirty years ago. He does interesting things rhythmically, but I don't use that in my writing because it would be too forced. But I use a lot of what he does harmonically. I don't do it by studying it in detail, more by osmosis, it influences what I'm already hearing.

AAJ: I can hear jazz coming out of Messiaen's music. One piece I'm familiar with, "From the Canyons to the Stars" was inspired by his visit to the American west, particularly Utah. He plays freely with sounds, motifs, rhythms, images, melodies in the spontaneous way a jazz musician might.

TL: That's a piece he did near the end of his life that I haven't heard yet.

AAJ: You're really giving me a sense of how you and others can expand your composing and improvising by tapping all these musical sources. Jazz seems particularly suited to importing all kinds of music into it. One time, you said that Gyorgi Ligeti (1923-2006) influenced some improvising you were doing.

TL: I love Ligeti. I particularly like him because he didn't set out to compose in any one system. He might have tried ideas from a particular system, but he didn't feel any compulsion to stick to it. I love that he had no dogma.

Two Groundbreaking Compositions: Seven Vignettes from Broad and Lombard and Man Ray Suite

AAJ: Like you yourself. You seem to prefer to go with the flow of what's happening in the group and what's happening inside you. You're well known as a pianist. But I don't know how many jazz fans are familiar with you as a composer. I've heard a number of your compositions, and I especially appreciate your extensive compositions for jazz ensembles. I love your Man Ray Suite, but you also wrote a piece I've never heard, a very unusual one dedicated to the folks at a local senior center! I see that it's called Seven Vignettes from Broad and Lombard, referring to the Philadelphia Senior Center at that location, which happens to be near the University of the Arts and CAPA, the Philadelphia High School for the Creative and Performing Arts, each of which has great jazz studies programs. Could you tell us a bit about that composition?TL: The senior center piece came about when I got an American Composers Forum Community Partners Grant. They pair with community organizations, which in this case was the Senior Center, as they celebrated their 65th anniversary as the oldest senior center in the country. It's not a nursing home, by the way. It's a place where they have various health and fitness services, classes, and other activities for those over 55 actively living in the community. The grant partnered me with the senior center. To get ideas for a composition, I went there for a few weeks, met the people who hung out there, recorded some interviews with them. I got an impression of what they were like as people, and so on.

The music thus has a back story to it, but you don't have to know the story to appreciate it. But as a composer, having this back story of seniors helped me come up with ideas I might not otherwise have had. The piece has seven movements. I called the first movement "The Hum" because when you walk in you immediately experience a flurry of activity. It was a very high energy place. Very exciting, lively. Therefore, one of the movements was a tango, where on the bridge I gave it a Prokofiev kind of twist and then a little "Giant Steps" moment. It came about when I met a guy in his 80s who was just starting to learn the Argentine tango!

AAJ: You just overturned all the stereotypes about the elderly! I do know how much music can re-vitalize elderly folks. There's a wonderful film documentary called Alive Inside: A Story of Music and Memory (Projector Media, 2014) showing how music can trigger memories in people with advanced Alzheimer's Disease. More and more, musicians are helping patients in nursing homes and hospitals today. Your composition comes right in the middle of that development.

TL: So then, I got another idea from one of the librarians at the center who loves country music. It starts out with a sing-song melody, vaguely like a country tune. So the piece is basically the result of my free associating to what I experienced with the people there. It formed the basis for the music, in some cases more literally than others.

AAJ: The connection between music and life experience is both interesting and puzzling to me. How a song, essentially a rhythmic sequence of notes, can convey something about love, or even a feeling of the ocean or a scene in a garden. And you seem to get right in the middle of that transition of one into the other. That's not only true of the Seven Vignettes but maybe even more so of your Man Ray Suite which is based directly on your experience with several works of art by him that are in the Philadelphia Museum of Art's collection. And you made some wonderful jazz ensemble music from it. One of Man Ray's works is a real metronome with a picture of an eye pasted onto the pendulum, which does suggest a connection between music and "seeing" or the visual arts. How did you get involved in such a project?

TL: That came from a different grant that was given to me by Homer Jackson's Philadelphia Jazz Project in conjunction with the Philadelphia Art Museum. [Homer Jackson is a visual artist who also plays a major facilitative role in jazz, which may partly explain how he came up with this particular grant idea.---Eds.] Homer gave me plenty of time to work on it, so I started out by reading a couple of biographies of Man Ray. Then I went to the Art Museum and found they only had one or two of his works on exhibit in the main building. But they have many of his other pieces archived in the Perelman building across the street, and they gave me access to all of them. I also went on line to see slides of his works in other museums and collections.

Tags

Interview

Tom Lawton

Victor L. Schermer

United States

Pennsylvania

Philadelphia

Don Byron

Bootsie Barnes

Larry McKenna

Bobby Zankel

Odean Pope

Dan Monaghan

Lee Smith

John Swana||, vocalists {{Mary Ellen Desmond

Joanna Pascal

Jackie Ryan

Gerald Price

Bernard Peiffer

John Coltrane

Dave Douglas

McCoy Tyner

Elvin Jones

Duke Ellington

Count Basie

Benny Goodman

Thelonious Monk

Benny Nelson

Al Jackson

Uri Caine

Don Glanden

Soomi Tanooka

Django Reinhardt

Bob Cohen

Al Stauffer

Art Tatum

Sonny Stitt

Joel Levine

Sy Platt

Ben Shachter

Wynton Kelly

Red Garland

oscar peterson

Miles Davis

Cecil Taylor

Ornette Coleman

David Murray

Herbie Hancock

Freddie Hubbard

Donald Byrd

Patrick Fink

George Burton

Luke O'Reilly

Lucas Brown

Tim Brey

Orrin Evans

Pete Smyser

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.