Home » Jazz Articles » Jazz Raconteurs » Patricia Nicholson Parker: A Disciplined Disregard for T...

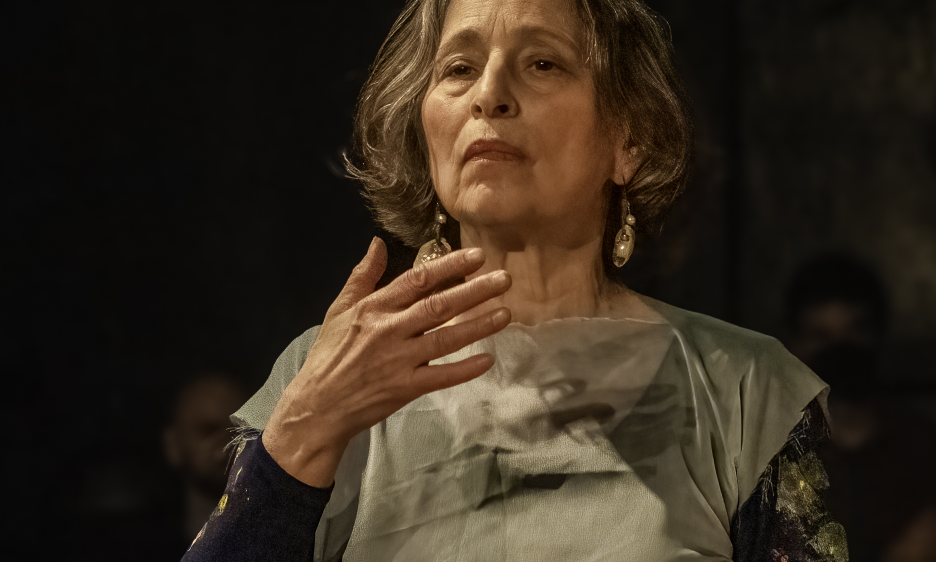

Patricia Nicholson Parker: A Disciplined Disregard for Traditional Boundaries

Courtesy Dave Kaufman

What I love about the music, and why I feel more at home in the music world rather than the dance world, comes down to how I define free jazz: 'a disciplined disregard for traditional boundaries.' The improvisation and the creative openness and particularly the connection to a spiritual source is what drew me.

—Patricia Nicholson Parker

All About Jazz: Could you start by telling us a little bit about yourself?

Patricia Nicholson Parker: From my childhood, I always liked to improvise. As I grew up, Improvisation was something specific that I wanted to do. I trained as a ballet dancer, but I was clearly ill suited for ballet for various reasons, including improvisation not being a thing one did in ballet. I grew up listening to all kinds of music, but jazz was most interesting because of its improvisation. But I hadn't heard the kind of improvised music I wanted to work with. And so I went about trying to find it, and that's how I met William Parker.

I met him at Studio Rivbea. He was playing with Muntu in December of 1972. I liked his composition the best. I spoke to him briefly after the performance about wanting to bring hope. Then William called me on January 1, 1974, and we decided to get together to form a dance and music ensemble. William was the composer. Although I had ideas about the music, he was such an amazing composer so the music became him. And I was the dance.

AAJ: Was the music composed largely for dance?

PNP: No, it was absolutely not composed for dance. It was composed with dance as an instrument.

AAJ: Interesting.

PNP: When I worked with other musicians, oftentimes they played for dance, and I felt like that they were playing down to me, which was annoying. But William Parker and our group didn't do that. What I love about the music, and why I feel more at home in the music world rather than the dance world, comes down to how I define free jazz: a disciplined disregard for traditional boundaries. It's not just a style; it's about the freedom to explore in all directions. The improvisation and the creative openness and particularly the connection to a spiritual source is what drew me. That's what made me feel like this was exactly what I was looking for, and this is especially true in William Parker's music.

AAJ: We would need several days to document all the things that you did.

PNP: In those days. I'm referring to the '70s into the "80s. Even though this was a very open time and very creative period in the '70s, people stayed in their lane. The dance world was going through a whole thing at this point, which I didn't quite identify with, but it was an exciting time in the dance world, but it was mostly conceptual and minimalistic, a reaction against traditional form. There was little crossover between the dance and the free jazz movement. The musicians were interested in dance, but I felt that dance was often just decorative to them, it wasn't valued. There are notable exceptions, like Bill Dixon and Judith Dunn or Dianne McIntyre and Ahmed Abdullah and Cecil Taylor always loved and respected dance. Another exception would be the Black Artist Group from St. Louis, which only lasted a few years. That was truly a multi-arts organization. But here (in NYC) dance was not a part of the free jazz scene. William Parker's collaboration with dance may have held him back slightly. I don't know if it did or not, but it didn't help that his main band was with dance.

AAJ: It was seen as esoteric.

PNP: I think it was seen as less valid. My favorite early review that I received; I don't remember who wrote it, but someone reviewed a performance that I was in with William, and they said, "I was surprised, I didn't hate the dance." That really says it all. He was expecting to hate it and shared his surprise that he didn't. It wasn't easy as a dancer, an artist. Also, by the mid '80's I was raising two children, one at a time actually, because there were almost ten years apart.

By 1994 there was hardly anywhere to perform in NYC. William was saying that he didn't see any other musicians except in Europe or at funerals. And I said to myself, this is terrible. Let me see what I can do. At that time, I had been going to University of the Streets, on the corner of Seventh Street and Avenue A., a block from our house. They held a late-night jam session that served people in the bebop strain. I would go there because I could sit in. But it wasn't particularly friendly. The better musicians accepted me, but the place was weird. Anyway, that was the only place I could go. And there was nowhere else to go and improvise. William Parker was not going to go to a jam session at that point in his life. So there was really nowhere to play much in New York.

AAJ: But that's okay.

PNP: There was the Knitting Factory, but the Knitting Factory primarily served a different scene and only occasionally had people from the free jazz scene. It wasn't a space that was built around Black Creative Music. So maybe William Parker and Roy Campbell, etc, would do a few gigs a year there, certainly not enough to sustain a black improvised scene.

AAJ: Can we pick up a little bit on that? So it seemed in the '90s and into the early 2000s there was a lot of fracturing in the community.

PNP: Yeah.

AAJ: Yeah. You know, the biography talks about a jazz war and specifically Stanley Crouch. Even with the avant-garde scene, there seemed to be pockets that didn't communicate all that frequently.

PNP: Well, the thing is, to understand this is to really understand systemic racism as well. There was also of course systemic sexism. I think the reason that dance was seen as decorative because it was usually female. And that still exists. People have always enjoyed women in bands especially if they're young and pretty and available.

AAJ: But if you fast forward there's so many successful females, particularly in the more adventurous side of jazz.

PNP: Now there is. Yes.

AAJ: Yes. Yeah.

PNP: But let's talk about that separately because that's a whole other kettle of fish. Back in the '70s, '80s, and '90s, things were different. I'm talking about systemic racism here. Back in the '70s when I met William Parker, the music scene was about 80% Black. There were definitely some white musicians around, but by the '80s, that changed. To give you another example, in William Parker's generation, there were lots of young Black musicians and some white ones all making their mark in this free jazz scene. They were all part of it. Then, after William's generation, the next important black musician to emerge was Matthew Shipp, and that wasn't until over ten years later.

AAJ: Maybe late '80s?

PNP: He came in the mid-'80s. William came on the scene around 1970. But I met him in '73 at Studio Rivbea. During this period, you had Jemeel Moondoc's band Muntu that William was playing with. There was Daniel Carter, Billy Bang, Roger Baird, Malik Baraka with Dewey Johnson, Earl Freeman in the Music Ensemble. there was groups with David S. Ware, Cooper Moore. Ahmed Abdullah and many others like Sam Rivers, the musicians from St Louis BAG and Chicago AACM. They were all happening making music at the same time in New York. And then they all either left and stopped playing in New York because there were no venues that would present this music. The press had dismissed the validity of the music by calling it angry and almost completely ignoring the New York scene. The next generation of Black improvisors wasn't for ten years when one new musician came on the scene, Matthew Shipp. Why the 10-year gap? Because somehow the music was no longer in the neighborhoods. And there's various reasons for that, which I'm not going to try to get into here. Then after that, the next African American to come on the free jazz scene was James Brandon Lewis.

AAJ: Much later.

PNP: Yeah, that would have been..

AAJ: almost 2010.

PNP: When James arrived he brought in Luke Stewart and a few others and then things began to open up a bit more.

AAJ: You know, we just did a feature on James.

PNP: Yeah.

AAJ: So. Yeah, he's brought a lot. He's brought a lot of energy.

AAJ: James and I had a very long and interesting conversation.

PNP: Yes, James is a private person but he has a lot to say. He's actually the one who did a lot of outreach and brought in more Black musicians. Now I've asked others to help with that important outreach. The traditional ways of communicating within our community had completely broken down by then. The music wasn't being passed on the way it had been before the '70s.

I started the Improvisers Collective in '94, and it lasted two years before evolving into the Vision Festival. There was someone who used to come to the weekly Improvisers Collective concerts who suggested we start a festival. And that's how the Vision Festival was born.

I was raised to serve others. That's how I was brought up. That was what I was taught was the right way to be in this world. And I wasn't really given a lot of support to just do my thing, my own art. So when I had all that pushback and didn't feel entirely welcome because I was a dancer and, and not only was I a dancer, I was a white dancer in a black music scene. I didn't fit, you know. So that's a lot to overcome. I still did stuff, and most notably a Thousand Cranes piece opera. That was my idea.

AAJ: Can you talk a little bit about that?

PNP: It took place on June 6th, 1981, the opening day of the Second UN Special Session on Disarmament outdoors in Dag Hammarskjold Plaza. I had been active in the anti-nuclear peace movement. I was part of this group called the Atlantic Life Community. The Thousand Cranes opera was inspired by the story of a little girl, Sedako, who developed leukemia as a result of the bombing in Hiroshima. She tried to fold 1000 cranes. Cranes are a symbol of longevity and she hoped that by folding a thousand paper cranes she wouldn't die. The opera doesn't try to tell her story. It's an anti-war opera. And I had this idea of the finale with a thousand school children singing this song that William Parker wrote. He wrote music and the lyrics for the opera and I conceptualized, choreographed and directed. A friend and I organized schools to bring children to sing the finale. We sent them directions on how to make wings.

AAJ: I'm sure, it was a very moving event.

PNP: Yes. It was. I was fairly young then and it was hard to pull off, as you might imagine—choreographing, fundraising and organizing schools. But I'm a fighter. I don't back down. If I think I'm doing what I'm supposed to be doing, I don't back down. This is probably why Arts for Art has continued. Because, you know, there's always been times of resistance.

AAJ: And I'm sure challenges, financial challenges, other challenges.

PNP: There are financial and other challenges, but. I love the work that I've done. I'm proud of it.

AAJ: It's a remarkable body of work.

PNP: I realized sometime in the last ten years that the ideals and ideas of Arts for Art and the Vision Fest are really my own. And I need to take my own artistic work seriously. I need to make more space and time for my own creativity. But this isn't easy as I also feel responsible for my community. But now, I am beginning to do this. I had felt that Arts for Art was worth investing my life in because art is that important. I believe in art, especially the art that people would erase. Now people talk about erasure, right? Well, many young white people have embraced this music from Black culture. At the same time it was no longer available or a part of the culture in black neighborhoods. This went on to the point where some young Black people don't even recognize jazz as their music. Anyone can play it, but they don't acknowledge it as Black music.

What I am saying about erasure is that when it comes to African American music, it's different. Like with Irish music, no matter who plays it, it's always called Irish music. But when others play African American music, it often loses its identity; it's not usually referred to as Black music that others are also playing. This is one symptom of systemic racism.

AAJ: Would you say that's something that started in the 1960s?

PNP: No, I think it was always there. Okay. This erasure was always there. Back when jazz began, there was this white musician from New Orleans that tried to claim that he invented Jazz.

AAJ: Yeah. No, I know who you are referring to. Its Paul Whiteman and lots of others later.

PNP: Yeah, that's it. There's always been this.

AAJ: Right. But within the Black community?

PNP: Within the Black community. What? Um. How did it lose its identity there?

AAJ: Yes, essentially. I mean, that seemed to really start in the '60s, where?

PNP: Oh, yeah, there was a loss of jazz in all forms in Black communities that happened in the '60s and '70s. For example in 1972, the all-Black station WLIB had been playing a range of Black music from R&B to John Coltrane to Albert Ayler. It suddenly stopped and became WBLS. In 1980 WRVR shut down overnight and it went from jazz to a country music station. This was discussed at last year's Vision Festival conference. We discussed how the music was taken off the air not only in New York. If music isn't available or heard, it doesn't get passed down. As it became less of a pop music, there were few opportunities to share it. And at that time there was little to no funding available. So, the music became less available in Black communities. At the same time, the so-called urban renewal was destroying neighborhoods that had once supported creativity on a very local level.

AAJ: That was a pervasive trend.

PNP: I cannot speak for how others (specifically Black Americans) are feeling. But coming from my experience as a parent and protector of children, as a mother and wife and as someone who has committed much of my life to sustaining Black Creative Improvised Music a/k/a free jazz-being a Black American isn't just about pride; it's about defiance. You know, there's so much history tied up with slavery and other negative stuff that to feel proud and good about being Black American, you almost need to overlook the whole American experience. How do you feel proud of being a slave or being constantly made to feel inferior. Schools only started acknowledging African-American achievements in the '60s, and even then, they barely touched on cultural achievements. They'd mention George Washington Carver and agricultural innovations, but rarely the writers, and they certainly didn't focus on the music. Jazz, for instance, was always considered just pop music, so it never received funding or very much acceptance by white-dominated cultural institutions. Nowadays, jazz can get funding, and jazz has become mostly white, but back when we were younger, there was no funding. Black music was just seen as pop music and therefore didn't need or warrant support.

Pop music is supported by the listeners. So the fact that record distribution wasn't happening correctly, even when the record exec liked the music, it was the distributors who didn't want to distribute the free jazz stuff. And If the music isn't on the radio and it's not being distributed properly, it's not available in the community. How can you hear this music? What people heard is the pop music that's hitting the charts. And so, if you're poor, and you are into music, you're going to want to play music where you can make money. If they don't play jazz on radio then you don't know much about it and it is no longer contemporary and therefore you wouldn't think that you could make a living playing it. Additionally, sometime during this period they also shut down most of the music programs in the public schools. And for those who played free jazz, it was very difficult to support yourself. We were living in, William and I lived in poverty. For the first 20 years, we were definitely below the poverty line. I would collect bottles.

AAJ: William had some very good gigs along the way.

PNP: When he worked with Cecil Taylor he made good money. That wasn't regular work, though. It was great. And what the experience was, he'd go to Europe, he'd go to stay in nice hotels and perform in concert halls. Then he'd come home with some change. The chunk of change which would pay maybe a month or two rent, I mean, and then you wait three or four months before you have another tour. So during that time we were on welfare. So with that, you came from staying in fancy hotels, playing in Europe, you know, and being well-respected to coming back here. I would collect bottles with the children. I mean this really was a shocking kind of displacement.

AAJ: I think a lot of things that you're saying lend an understanding to how you gave rise to this community and how that's played a vitally important role. So I think Arts for Art and Vision Fest brought a whole bunch of different things. I mean, as you said, there was dance and music.

PNP: Just like I said, I'm a fighter. I fight for what I believe in, what is important. The music, the art, the dance the poetry and diversity and social justice. Even at the first Vision Festival, we were political. There was dance and poets like Baraka and an art show, We even put out a poetry book.

AAJ: And so from the beginning you were committed to having to this being a celebration of the arts.

PNP: Diversity, equity, inclusion. Before we knew about DEI.

AAJ: Yeah. That's true. Very true. But also inclusive. I think there's some misnomers about The Vision Fest about the kinds of music that are included. There's a great openness to a lot of different kinds of music. So, you don't have barriers or inclusion criteria. Artists that you would not necessarily expect to play the Vision Fest are often invited to do so.

PNP: There was this idea that you have to stay true to your core community for what you really love. But if you're not keeping your edges open, then you're insular. It's just not a healthy environment if I only book those artists who I like. If I don't book anyone I don't like, then I'm not doing a good job. It would be just, you know, just too precious.

AAJ: I think that people have this perception that free jazz is a narrowly conceived musical style. It's not a monolith. The incredible diversity of styles that you see in the Vision Fest is really remarkable. And I think it opens one eyes, one's eyes to the possibility of music labeled free jazz. The scope of it is so much greater than the narrow band that label denotes in the public's mind.

PNP: Someone told me, someone who really loved the Vision Festival that free jazz was really for a special, elite, well-educated clientele. And I hated that so much that I almost did everything I can to make it not true. It's particularly important that we not be elitist, that was never a good idea. And it's now a terrible idea. We're at a time in this world that we need to go out of our way to find ways to bring in more people creatively and also audience wise. I'm going to start working with DJs and things like that because we need to. There are these random demarcations. It's like dividing and conquer. Not everyone likes to dance, obviously, but I do. We can't be serious all the time. We are intellectual at times and sometimes we want to be joyful or we want to be all the different aspects of who we are. All aspects have their place in a healthy community. So I think we need to radically reopen ourselves. And at the same time keep the ideals clear and straight and right out there. Because the world needs that. I mean, it needs an unequivocal idealism, but it needs an unequivocal openness and inclusion.

PNP: And that's why the festival is entitled Bridges this year [2024]. Or Building Bridges. My own piece that I am going to perform at the festival is called "Holding Bridges, Falling Down."

AAJ: The Vision Fest and Arts for Art has been committed to social justice and promoting other causes of peace since the very beginning. It's a very important part of your mission. It informed the festival in important ways and infused many performances. You are creating an experience, but it's not like you're lecturing to people. You always try to strike a balance. You want it to be a joyous occasion, and you want people to have a good time.

PNP: That's exactly what I'm trying to do. Thanks for seeing that. Why shouldn't good people enjoy life? It's the bad ones who should be suffering, right? If you've got a good heart, you shouldn't be the one getting knocked down by all the wickedness out there. We're here to spread some goodness, so we should be as joyful as we can. Sure, the world throws challenges our way, but I'm here trying to create chances for joy—without keeping our heads in the sand.

AAJ: That was beautifully stated, I think, that's right on. Not to delve too deeply into the politics of it, but on some years we're, you know, we're collectively feeling down because of the state of affairs. You're cognizant of that and say, okay, we have to dial that back. Give people the opportunity to escape that a little bit.

PNP: Then we started Artists for a Free World in January 2016 we participated in 34 demonstrations. It was in these demonstrations that I realized that free jazz really belongs on the street. As long as there's a solid rhythmic element, people love it. So seeing how much everyone was loving what we were doing. And how hard it is to get people to come to events. It sort of clarifies how organic this music is, how easy it is to relate to.

Let me break this down because I enjoy breaking this down. What happened during the demonstrations was, you had a rhythm, right? People were playing percussion, keeping the beat. We had simple melodies—like, there was this one piece by Roscoe Mitchell, though I can't remember the name, and another simple tune by William Parker. We threw in a few simple lyrics too, but the horns? They were going all out. Their solos were completely free jazz. And everyone got it, because those solos, that was the cry of the people.

AAJ: Okay

PNP: And if you give them something that they can understand, like the rhythm, then everyone also understands the freedom of that of a real improvised, open-ended solo. Because that's what everyone wants. Everyone wants to feel that open-hearted place where you're just part of the universe. That is quite different from a solo that you practice in school. You may play it alone, but it's not a truly improvised solo. It doesn't feel like the Cry of the People.

AAJ: So that's very well stated. I want to be respectful for your time. I think that we have a little bit more time.

PNP: Well, I'd like to talk about two things before I wrap up.

AAJ: Go ahead. And I have some things to ask you about, too, so please go ahead.

PNP: Well, I want to talk about this time, this moment for Arts for Art and this moment for Patricia. This moment is all about setting up what I believe will keep this organization going strong in the future. We're laying a solid foundation to ensure our long-term sustainability. A big part of this is our ongoing artist series. It's not just about artists curating but it is also giving them support and guidance to curate their own events effectively. This helps our music succeed, draws in new audiences, and brings new venues into the fold. It's a major part of our rebuild, making sure the things we start now can keep going strong, even when I'm not around, so that it can really stand the test of time. And it's about ensuring we pass on what needs to be passed on.

And part of that then also leads to Patricia. So. I'm. Like I said, what I've been doing all these years is supporting art that carries these messages. You know, things have expressed even here. And that's in my art, too. I'm hoping to make that more visible going forward. I'm going to try to get out from under the total weight of Arts for Art and shifting that weight. So it has legs for the future. The reason no one knows about me as an artist is because they can't get past Patricia as an organizer who couldn't even be seen that way because people would want to give the credit to others.

AAJ: I understand how people can see it that way.

PNP: You know I don't cry over spilt milk. I'm all about the future. I'm all about the present and the future. All my past and my history educated me. So I want to share my education with other artists, and I want to share my understanding and my creativity through my own work as well. I want to dance, sing and shout. I want to make my own art that speaks loudly to support peace to support kindness and justice. I may not be known for my art but I plan to be a lot more present on the scene as a free jazz dance/poet/creative improvisor.

AAJ: Arts for Art has always embraced the label "jazz." Others have referred to it as creative improvised music or black improvised music. Since the beginning, jazz has been a focal point of the Vision Fest. It's the oldest standing jazz festival in New York City. Can you comment on that?

PNP: Yes. No musician that I know of likes the word jazz. I insisted on using it for a very long time because I was fighting the erasure of it as Black music and jazz may have negative connotations or insulting ones to Black people because of association with brothels. But nonetheless it also has an association with Blackness that I thought you if I took away that word jazz from free jazz, then you have free music. Free music is similar but different. It was a European idea. And it was freedom from jazz.

AAJ: For example, not steeped in the blues.

PNP: So it was very clearly saying I'm not Black. So I'm certainly not going to use free music because I was trying to really place the Blackness in there and maintain it and hold it, make space for that. Finally last year I began to refer to it as either Black and multicultural or just multicultural, depending on the situation. None of the musicians give me negative feedback on it, but it's also long. So I will write about it that way. And I'll also say free jazz. But musicians themselves, you know, they hate titles. But creative improvised music is fine. I never liked the phrase creative music by itself without the word improvised connected to it, because creative music is what they teach in kindergarten and I didn't want this great music to be in any way, diminished. You know, I was trying to give it the respect.

AAJ: But I think, you know, nobody wants to be pigeonholed and genres tend to do that. On the other hand, we as listeners need categories. Unfortunately, they are necessary for our understanding, for points of reference, right? I've been a jazz fan since I'm 16 and I've never been a musician. But it's been an important part of my identity. And I don't feel any ownership of the term jazz. And I fully understand people's experience. So not only what you refer to, but also the fact that particularly in the in the '80s and '90s, but even beyond jazz critics would listen to Henry Threadgill and say, oh, that's not jazz. You know, that was a common refrain, maybe going back to Ornette Coleman and saying, oh, that's not jazz. And so musicians have also had to live with that stigma.

PNP: An example was in in the early '80's or late '70's William applied for a grant under "new music" and he received his rejection under jazz.

AAJ: You can't win either way, right?

PNP: No. Well, it was like, this is all racial. It's really racial. And if you remember Roy Campbell.

AAJ: Yes

PNP: Well, yeah, of course you do. Um, young people won't, but. But anyway, he always talked about how he felt that people didn't want the music to sound too Black or as he said it "crude oil," the Blackness in the music and the aesthetics that are associated with African-Americans. There was so much resistance to that, it's just so disturbing. What a crazy world we live in.

AAJ: Yes, it is quite extraordinary.

PNP: But you know, I was very thankful when they when they started using the word systemic because before then there wasn't the language to communicate what I was seeing. I had held a panel on racism and no one was comfortable. It felt uncomfortable to talk about racism publicly because, amongst the general public, the common myth was that racism didn't exist. And Black people who lived it didn't think it would be constructive to discuss in the open. I was trying to bring it up, make it public, because I kept on seeing it as a big problem.

AAJ: I think one positive thing that's changed over the last five years is people have come to understand racism in a different light and systemic racism, and it's not only a product of people who are overtly racist and expressed racist views, it's ingrained into everything. Right?

PNP: I used to explain about how people react differently to unfair treatment, and it really puts racism into perspective. If a white person is treated unfairly, they're likely to make a big fuss and demand their rights. But historically, if a Black person faced the same situation, they are more likely to just shrug it off. It wasn't that they don't care—more like it was safer not to rock the boat. Things are slowly changing, though. It still really depends on where you live and how safe you feel standing up for yourself. That's why if you're Black, you're likely to shrug your shoulders, because anything more than that, anything more than that was dangerous, it could get you killed.

AAJ: Understood. Switching gears somewhat. Arts for Art and the Vision Fest, in particular, has had a very loyal community. Some people have attended every single Vision Fest.

PNP: Yes there are these beautiful core audience members. But I've been fighting to have our community grow, trying to figure out how to make it grow. And I think that we've had successes.

AAJ: For sure you have.

PNP: I just think understanding what you're up against is key to creating success. The anti-elitist approach is crucial here. We've got to stay open and creative, not just in our music but in how we connect with our community. That's what I'd say. I mean, there was a time when I thought about community, I was really just thinking about the artists, the volunteers, everyone involved in making the event happen. But I wasn't really considering the audience. Then it hit me—they're a big part of the community too. That realization changed everything, and it was quite a while ago now. That's why it's so important to make the experience great for everyone. And I think we're pretty good at that.

AAJ: Absolutely. It is a really unique experience.

PNP: I think it's essential to make our space welcoming for the younger generation, as they are the future. We need to focus on what it means to be inviting and accommodating to their needs and perspectives while at the same time respecting those who have been following this and supporting in ways that they can.

AAJ: I think in the last few years there has been a growing younger audience. Not in huge numbers, but definitely present.

PNP: That's exactly what we're working on. It's something that needs to happen, so we're on it. But, honestly, we're still fighting an uphill battle. We're handicapped by the erasure of history from years ago, and the fact that jazz was demonized hasn't helped.In popular TV shows, and they'd always talk about jazz as a negative. It makes the job of reaching out to young people harder. Because we're fighting against messaging that's coming from mass cultural outlets.

AAJ: And trying to convince a community that...

PNP: This is your music.

Tags

Jazz Raconteurs

Patricia Nicholson Parker

Dave Kaufman

Fully Altered Media

United States

New York

New York City

William Parker

Bill Dixon

Judith Dunn

Dianne McIntyre

Ahmed Abdullah

Cecil Taylor

Roy Campbell

Jemeel Moondoc

Daniel Carter

Billy Bang

Roger Baird

Malik Baraka

Dewey Johnson

Earl Freeman

David S. Ware

Cooper Moore

Sam Rivers

Matthew Shipp

James Brandon Lewis

Luke Stewart

John Coltrane

Albert Ayler

Kris Davis

ambrose akinmusire

Tyshawn Sorey

Reggie Workman

Joelle Leandre

tomeka reid

Melanie Dyer

Kidd Jordan

Marshall Allen

Sun Ra Arkestra

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.