Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » Miles: The Autobiography... Two Decades Later

Miles: The Autobiography... Two Decades Later

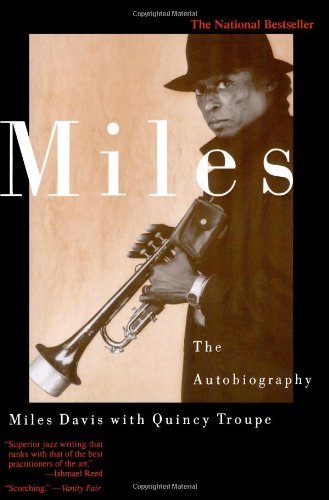

Miles: The Autobiography

Miles: The AutobiographyBy Miles Davis with Quincy Troupe

New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 2005

(Originally published in 1989)

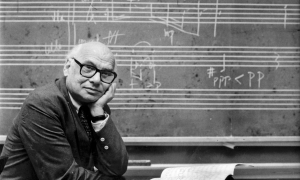

Miles Davis knew how to keep himself on the radar screen. He did it musically throughout his life, except for a five year period of "silence" when he isolated himself in his Manhattan townhouse, by his own admission musically inert and completely caught up in drugs, alcohol, and sexual escapades, inaccessible to even his closest friends. Even then, his records continued to sell, and he made money. Today, nineteen years after his somewhat untimely death in 1991 at the age of 65, he continues to remain a musical legend, still quite popular as well, and undoubtedly his estate earns considerable royalties from his recordings and other productions. Part of Davis' enduring success is due to his enormous musical influence, creativity and productivity. Beginning with the Birth of the Cool sessions, he showed his remarkable ability to bring a group of musicians together to create groundbreaking music. However, a significant part of his fame and success is also due to his well-cultivated image as the quintessentially rebellious, individualistic black musician, the artist against the Establishment, his insistence on being himself, the African American insisting on being free. This image is perpetuated by his autobiography, co-authored by Quincy Troupe, who in an Afterword, indicates that he spent countless hours with Davis, taking copious notes and taping extended conversations with him. Moreover, he devoted himself to capturing Davis' language and intention. So, in two decades retrospect, and without being able to question the primary author, we can assume that this is Miles speaking, not the pure construction of his co-writer.

To cap such a career and life with an outstanding written record of it put one more notch on Davis' list of accomplishments. Indeed, it is truly remarkable to read his autobiography a little more than two decades after it was written and find it still to be a vital and electrifying document and probably the best jazz biography of all time, if not one of the great memoirs of any historical or artistic personage. There are two reasons why this book deserves such praise. One is that it is supremely truthful, belonging among the veritable confessional masterpieces that only rarely appear in the literary landscape. Over and over again, Davis discloses his darkest moments and his failings as a human being (though he unrelentingly tells us how great a musician he is!), not so much seeking redemption as wanting to reveal his whole self. Davis' anger and impertinence, his drug and alcohol addiction, his periods of insanity, his machismo abuse of women, his financial ambition, his narcissistic displays, and his resentment of all authority are repeatedly put on the chopping block, frankly and directly, in the manner of one looking at his life with clear eyes, neither remorsefully nor with braggadocio. We see the man in all his glory, misery, and failings. It is a real credit to Davis that, given an opportunity for a written legacy, he put himself out there so honestly and completely.

Musically, the book is richly filled with story, analysis, and reflection. He takes us right on through his early influences and inspirations, such as the Billy Eckstine band, Clark Terry's interest and guidance, and his attraction to a slew of lesser known players; through his tailing Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker in New York; to his co-creations with Gil Evans as well as his remarkable quintets, and his landmark recording, Kind of Blue; his sojourns in Paris and the rest of Europe; and his experiments with post-bop and fusion genres. He recalls everything in minute and vivid detail, for example, the time that J.J. Johnson came up to his apartment to find out about one note in a Dizzy Gillespie transcription—that's how devoted these guys were to doing it right. The details make you feel that you are there when it's happening, and gives a genuine sense of the exchanges among these innovative musicians. With the exception of the very last chapter, when he struggles to sum it all up, and does so mostly in clichés, the narrative is powerful and absorbing, and often enlightening about the musical developments in which Davis played so crucial a role.

The style of writing is conversational and informal, and its use of profanity will take some readers aback, as Troupe acknowledges. It would be interesting to know if Davis actually spoke that way. The constant swearing has echoes of the great Rimbaud, and epithets are often paradoxically complimentary. For example, a "bad m—f--" (Davis did not bleep these words) is jazz lingo high praise for a fellow-musician's capabilities. But I suspect that even some of Davis' closest friends, and particularly those who were deeply religious, would be put off by the frequent profanities, which in any case saturates the prose just a bit too much. In a way, the reader has to filter out some of the language to get at the real poignancy of Davis' experience, such as his troubles with family, co-musicians, and the music industry; his ignoring a handwritten note from his father just prior to the latter's death; and his absolute love and affection for Gil Evans. As one can hear especially in his expressive solos in Concerto de Aranjuez and Porgy and Bess, and with all his bravado, Davis was a sensitive and deeply emotional person, and his bonds with close friends and fellow-musicians contradicted his intolerance for audiences and critics.

The question of Miles Davis' personality and character surrounds any reading of this book. He was known to be dismissive (I remember attending a set he did at the Vanguard in the early 1960s, when he played throughout with his back to the audience, a well-known ploy of his. Oddly, I was not offended, probably because the music was so good.) He could be arrogant, quixotic, impulsive, flamboyant (he was a clothes connoisseur and sometimes wore outrageous attire), and abusive. Yet he could be supremely well-organized about the music, and some remember his capacity for warmth, caring, and affection. Part of the understanding of these paradoxes seems to have to do with his attitudes towards race and authority. In the autobiography, he presents himself as hating white people, not as individuals, but for the egregious way they treat African Americans and their music. And of course, he's right in many respects, and the racist card still has validity, maybe always will because human differences and subjugation appear endemic to society's need to privilege some groups by denigrating others. Yet at times, Davis' critique of whites has the quality of a rant and of inverse racism, which many African Americans, such as his friend, James Baldwin, himself a staunch and articulate critic of racism, would find abominable. Yet at times, this same "rant" has the quality of a strange kind of courage, and you find yourself on Davis' side all the way. He never gives in to established authority, and we'll always need such rebels in our midst to keep us on our toes.

In my opinion, Davis' anger at whites and authority figures is a reflection of his difficulties establishing his own masculinity. He is a truly sensitive, vulnerable man, almost a boy-man, and he wants so much to be a man's man. He studies prize fighting, he beats up cops and women, he fires players sometimes impulsively, changes his groups around too often, and cavorts with the rich and famous. He's trying to be a tough, "real" man, and paradoxically, with all his anger towards white folks, he ends up trying to be like one of them. It is not particularly African American to drive expensive sports cars, go on holidays in the French Riviera, go to coffee houses with Jean Paul Sartre, and make out with movie starlets. It's possible that Davis unconsciously envied white people and tried to be like them. That's not what W.E.B. Dubois, Martin Luther King, and Malcolm X had in mind.

But, again paradoxically, part of Davis' creativity may stem from his ability to be both "black" and "white" at the same time. What comes through in his autobiography is that his greatness came from his ability to take the roots of truly African American and Afro-centric blues and jazz, "America's classical music," and combine it in unique and diverse ways, and taking a cue from Bird and Diz as well as Gil Evans, with European musical forms to produce a variety of new expressive styles and approaches for jazz groups. His brief and truncated experience as a student at Juilliard was always with him. The truth is that Miles was not as great a trumpet player as he comports himself to be in this book. Indeed, he admits that his friend, Kenny Dorham cut him to pieces when he sat in on one of Miles' gigs. His greatness lay in his ability to create and renew and invent the music itself. He did this not once, but many times in his career, coming in on the heels of bebop, practically defining "cool" jazz (with Gerry Mulligan and others at his side), elevating hard bop to an art form (along with Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Art Blakey, and many others), practically defining modal playing (along with Thelonious Monk, Trane, and Bill Evans), bringing rich thematic material to post-bop playing (along with Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea, and their peers), deeply enriching the jazz fusion movement and electronic instrumentation, and late in his career creating a series of idiosyncratic recordings incorporating diverse cultural and musical influences.

As the autobiography makes clear even today, a couple of decades after it was published, Miles Davis changed the face and voice of the music many times in his lifetime. His legacy continues to exercise a powerful influence even now. His musical originality and resilience is his redemption and his manly beauty, and it gives cause to wonder if this was the reason, in his own vernacular, for all his other "shit." In this respect, he mirrored in his life, his autobiography, and his music the essence of what the literati call "modernity." As the title of one of his albums, Live/Evil, suggests, Miles Davis may have needed to go into the darkness in order to find the light.

Tags

Miles Davis

Opinion

Victor L. Schermer

United States

Billy Eckstine

Clark Terry

Dizzy Gillespie

Charlie Parker

Gil Evans

J.J. Johnson

Kenny Dorham

Gerry Mulligan

Sonny Rollins

John Coltrane

Art Blakey

Thelonious Monk

Bill Evans

Herbie Hancock

Wayne Shorter

Keith Jarrett

Chick Corea

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.