Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Large Ensembles: Is There a Place in This Large Music World?

Large Ensembles: Is There a Place in This Large Music World?

Duke Ellington

Duke Ellington

In the post-World War II era music began to change, as the harmonic and rhythmic breakthroughs of bebop began to impact the music. The standard bearers for the new movement were small combos, where the major soloists got more room to express themselves, and became bigger stars. The music contained European influences of Stravinsky, Bartok, Ravel and Debussy.

But big bands fell out of favor. Financially, it was always tough to keep large group on the road. Ellington was fortunate enough to subsidize his efforts with his considerable royalties, and keep men on the payroll even when they weren't on tour. But even his group fell on hard times. Basie disbanded in 1946 and didn't reconstitute it until the '50s. Dance bands became hard to find.

Performers like Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck and others were in vogue.

But big bands have always survived. Ellington kept going until he died; Basie as well (bands under both names have carried on, posthumously). Thad Jones and Mel Lewis, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Maynard Ferguson and others continued to have good runs. There are still organizations with regular gigs in New York City, like the Vanguard Orchestra, and Sue Mingus has kept the legacy of her husband, Charles Mingus, alive with various large ensemble formations. Wynton Marsalis has Jazz at Lincoln Center; John Clayton and Jeff Hamilton get to stretch their big-band legs when possible, among others whose names can't all be listed.

But it's still a precarious undertaking. The cost is large and the demand, not so much.

Yet it's still attractive enough for veterans like Charles Tolliver, and younger men like Guillermo Klein, Arturo O'Farrill, Jason Lindner and John Hollenbeck—again, among others—to proceed.

Maria Schneider has paved the way in recent years with her fabulous orchestra, a Grammy and armfuls of industry awards. Darcy James Argue composes and arranges for a fine group in New York City that is rising to critical acclaim and gaining a following.

Maria Schneider has paved the way in recent years with her fabulous orchestra, a Grammy and armfuls of industry awards. Darcy James Argue composes and arranges for a fine group in New York City that is rising to critical acclaim and gaining a following.

Many of the young composers—a large number listing Bob Brookmeyer among their main influences—are people who have tasted different kinds of music along their journeys and are incorporating those elements in their work; jazz being inclusive, not exclusive.

There are other bands that continue to pop up, led by those who continue the legacy, getting gigs whenever they can and writing original music. They work hard. It's frustrating, but music lovers should be glad of that, as the music is vital and an important part of the tradition as well as the future.

But with the changing music industry, the beleaguered economy, the still-subservient status of jazz in the United States and all the logistical problems of maintaining a large group, a question one might ask about why young musicians are still carrying the torch is: Why? Why go through the headaches?

Chapter Index

- Ouch! Headaches

- Ahhh! The Music

- Influences

- Dave Rivello

- Jacam Manricks

- J.C. Sanford and David Schumacher

- Chris Jentsch

- Nicholas Urie

- The Future for Large Ensembles

- Ahhh! The Music

"It certainly is a love/hate thing," says Big Apple-based Nicholas Urie, a composer/arranger who released Excerpts From An Online Dating Service was released this year with his Large Ensemble (Red Piano Records, 2009). "I'm in the process of trying to get some gigs and it really is... You love the band because it affords you the opportunity to orchestra and to create sonorities that are compelling and beautiful and unique in way that a smaller group doesn't allow. At the same time you have to deal with economic constraints. Limitations of space. All of those things.

"Plus the logistical aspects of having a big band are sort of overwhelming. Keeping in touch with 18 people. Getting their schedules together. Finding a time. Keeping them happy. Making sure everyone's improvising enough. It can be very much a love/hate kind of thing."

J.C. Sanford and David Schumacher are composers and arrangers in a unique setting. They both write for and conduct Sound Assembly out of New York City. The band released Edge of the Mind this year on Beauport Jazz.

Says Schumacher, "Of course it's daunting. You've got to get 17 players together. The logistics that go into that is daunting enough, but also the financial responsibility that goes into that is pretty daunting. The reason we decided it was time to try this out is because at least one of us was going to be in New York. I kept hearing about there being such a pool of players to draw from that were going to be interested in this. In a sense, getting great people to play is not the hardest part."

Bandleaders say they are surprised that musicians of outstanding caliber are ready, willing and able to play new music with large ensembles if they get the chance. That helps the plight of a bandleader, but there is still plenty to turn a person's hair gray—or have it fall out in clumps.

"Finding a venue that's not a total drag" is another problem, says Sanford. "Not every club treats you great. It's hard to find a space that's big enough and can handle the sound of a large group like ours." he adds, "We can't pay a lot. We can't get people to turn down their tours to do our one little gig here or there. It's all rolled into the financial part of it."

"We started as a reading band and we were trying out new people and new combinations of people. Trying to get the voices we wanted in each section of the band," says Schumacher. "It took us several years to solidify the personnel. Then you get to that moment and you get very excited and you're happy to have that finally in place. Then you go to call the first gig and four of those guys can't make the gig because they've got another commitment. It is frustrating."

For Dave Rivello, who leads the Dave Rivello Ensemble in Rochester, N.Y., getting players has been easy because the Eastman School of Music is located in his city and so musicians are plentiful. "I couldn't have my band here if it wasn't for the school," he says. The band released Facing the Mirror this year, its first major recording (Allora Records). The music is not easy to play."

The Dave Rivello Ensemble

The Dave Rivello Ensemble

Concerning the business of big bands, Rivello notes with a chuckle, "I love the line I heard from somebody not long ago: 'Whenever you see a big band, somebody's losing money.'"

But he adds with satisfaction, "The guys love to play. I pinch myself every day when I wake up. These guys want to play. They're not concerned with the money. I've got a sub list longer than both arms of people wanting to get into the band. They stay in the band as long as they can, until they eventually go off into real life, teaching jobs or wherever they go. Some of them come back and want to get back into the band."

Brooklyn-based Guitarist Chris Jentsch leads his Jentsch Group Large, which released Cycles Suite (Fleur de Son Records, 2009), his third in a series of recorded suites. He says there are various reasons why it is hard for big bands, without big names, to get gigs.

"One reason is unless it's a really large prestigious venue, it's hard to find a venue that has a stage big enough for a big band; that you'd want to feel comfortable asking your friends to cram into. The Jazz Standard (NYC) is a great room for large ensembles. It's hard to get a gig in there. Places where I can get gigs, a lot of times it's very difficult to fit the band on the stage. I hate to ask the guys to struggle, since they're not getting a whole helluva a lot of money. I like to try to make it as pleasant for them as I can. I don't want to wear out my welcome by forcing them to sit on these tiny stages. Everyone is very understanding. I'm probably a little more conservative about asking the band to do that than I need to be. But I hate to see all those top professionals with those expensive instruments all crushed together."

The inability to tour is something that bandleaders understand. In an ideal world, they would gladly take off city-to-city with their bands. Groups with larger established names can do it to some extent—but even then there are woes, as the multi-award winning Schneider told All About Jazz in 2007. "It's difficult because it's expensive," she said. "It's 20 people. What's more difficult than getting the tour is actually doing the tour. I'm coordinating all these musicians. They're all freelance musicians. Trying to get everyone's schedules together when they're hopping all over the globe, each of them with several other groups. Getting the music together. Logistically, it's just an absolute nightmare. Sometimes I'm like, 'Oh, god, why did I start this thing?'"

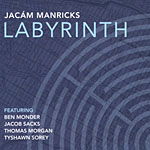

Notes Australian-born, now NYC resident Jacam Manricks, whose ensemble released Labyrinth this year on Manricks Music Records: "It is really difficult with a large ensemble without a lot of financial support. I'm touring to promote the album, but just with a quartet. I've reduced those scores to work with a quartet. They kind of stand on their own anyway. But there are certain part that I've added into the piano part...It's so expensive. Hotels and flights. Making sure the cats are getting paid. It's a lot of work, but it's worth it. It's an amazing way to make a living and to live. I'm grateful for the opportunity to do that. But at this stage to do a tour it has to be a small group."

Argue, whose band is starting to gain steam with the release of Infernal Machines (New Amsterdam Records, 2009) told All About Jazz at the end of 2008: "I'm not sure exactly what I'm doing with my life. This big band I'm running and recording is a totally unreasonable way to make music. It's like I've gone out of my way to create the absolute most difficult scenario in terms of hours involved in preparation, to actual minutes of music produced. But for whatever reason, the payoff has been worth it for me so far."

Argue, whose band is starting to gain steam with the release of Infernal Machines (New Amsterdam Records, 2009) told All About Jazz at the end of 2008: "I'm not sure exactly what I'm doing with my life. This big band I'm running and recording is a totally unreasonable way to make music. It's like I've gone out of my way to create the absolute most difficult scenario in terms of hours involved in preparation, to actual minutes of music produced. But for whatever reason, the payoff has been worth it for me so far."

That's because of the music itself. The art.

class="f-right">

"For me, to stand in front of an orchestra and conduct your own music and hear it come to life is like an out-of-body experience," says Manricks. That in itself—the labors of art manifesting into a breathing, living thing—is the biggest thrill and motivation for the bandleaders. "There's all that stuff that I wrote and now it's actually happening. And though this record was done with a lot of overdubbing, I've done a lot of conducting of my music with large ensembles, like big bands plus symphony orchestra, 80- or 90-piece bands. That's the real thrill. That about the best time you can have with your clothes on, to quote Miles Davis [Davis]. It's a real buzz."

"There's that satisfaction of having a really great gig," Sanford says. "One of the nice things about having different players—subs—is that people bring different things to our music that we didn't hear before or didn't intend. Both [Schumacher] and I, we're really open to the way people interpret things. But also with different rhythm section players we've had come through, it's like, 'Wow. He played that in such a different way than I conceived it and it's totally great.' I love the different flavor that a guy puts on it."

Rivello, whose band has regular Thursday gigs except for taking summers off, puts it succinctly. "There's no greater feeling in the world for me than hearing a new piece, but even hearing my music every other week or every week. To be able to stand in front of the band. It's all worth it then. ...For the most part there's always some moment of magic in the stream of the three hours or whatever the gig is. That makes it all worth it. I don't know how to explain it, really. I wish I could.

Rivello, whose band has regular Thursday gigs except for taking summers off, puts it succinctly. "There's no greater feeling in the world for me than hearing a new piece, but even hearing my music every other week or every week. To be able to stand in front of the band. It's all worth it then. ...For the most part there's always some moment of magic in the stream of the three hours or whatever the gig is. That makes it all worth it. I don't know how to explain it, really. I wish I could.

"People that don't know anything about what it feels like to stand in front of a band and have that feeling—I wish I could give that to the world somehow, and let them feel it. The people that sit in an office job, or hate their jobs, or whatever it is. If they could actually feel that just once. As soon as we start to play, all the headaches and the hassles of dealing with the club or stage manager, bad sound engineers. Any of that. It all fades away as soon as we start to play."

Adds Urie, "I think there's a kind of power to music for such a large group. A kind of power that's compelling to people. I think the reason big band music has stayed around for so long is just because of that. People develop a kind of affinity for it."

Each of these individual composers and arrangers has an individual vision for writing. It appears to be innate. The seed is watered by a desire to not only learn, but explore, and the rays of sun that nurture them come from a long and varied list of influences: music listened to over and over; teachers who point sponge-like minds in the right direction.

"There's no alternative," avows Rivello. "All I ever wanted to do from when I was a little kid was write music."

class="f-right">

For these composer/arrangers, the influences come from different directions. But one common source is Bob Brookmeyer, renowned for his prowess with the pen, as well as his trombone playing in various contexts over the years. He'll be 80 in December. He continues to mentor young arrangers through the New England Conservatory of Music.

Schumacher says "Brookmeyer is the biggest presence in my writing. When I began my studies with him, I had come from a place of very traditional writing and playing. I had studied with Branford Marsalis and an Australian saxophonist... very big proponents of starting from the beginning and going from there. So I was coming from that place. Then Brookmeyer turned my whole world upside down and showed me these different avenues. Working with him and studying his music was a tremendous influence on my writing."

Schumacher says "Brookmeyer is the biggest presence in my writing. When I began my studies with him, I had come from a place of very traditional writing and playing. I had studied with Branford Marsalis and an Australian saxophonist... very big proponents of starting from the beginning and going from there. So I was coming from that place. Then Brookmeyer turned my whole world upside down and showed me these different avenues. Working with him and studying his music was a tremendous influence on my writing."

Sanford also puts Brookmeyer, whom he studied with for three years, at the top. "The biggest thing I got from Brookmeyer, amongst many things, was his greater concept of form. That's something I think is distinctive about both of our musics (Schumacher and Sanford) is this really clear concept of form and how everything ties together. We both got a lot of that from Bob."

Rivello studied at Eastman with Rayburn Wright, a highly respected music educator from whom Rivello took a lot and is ever grateful. He calls his association with Brookmeyer, which included working for him as a copyist, invaluable. "I consider that my doctorate... Words don't even describe what he gave me."

In fact, Brookmeyer wrote extended liner notes for Rivello's CD, commenting on each composition and saying Rivello is "someone I believe belongs in the next generation of composers... I look forward to hearing what the future has in store for him."

Says Urie, "in terms of craft-oriented things, Bob Brookmeyer has been a huge influence in terms of learning how to edit and create long, overarching forms and cohesive artistic statements." Jentsch and Manricks also acknowledge a Brookmeyer inspiration in their work.

But things that affect these composers come from far and wide, different cultures. And also the tradition.

Says Manricks, "I love Duke Ellington. The sophistication he had in his writing, especially considering what time he came out of. The late 1920s, early 1930s, writing amazing stuff. So inventive. I find that really inspiring music. Especially the Jimmy Blanton/Ben Webster band. I love Thad Jones. I love Basie. Bob Brookmeyer was also very influential on me. I transcribed a couple of his pieces. Gil Evans is definitely a big influence on me. Bill Holman is an amazing big band writer. Also a west coast cat, pianist and big band writer Gary Fisher. And more modern people like Maria Schneider. Claus Ogerman influenced me in terms of writing for strings and woodwinds and that kind of thing. I also got into classical music. I think you hear that in my CD."

Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Schoenberg and other classical musicians come into play. Explains Manricks, "Because jazz is a 20th Century art form, it ties in perfectly with the 20th Century classical composers in terms of the inventiveness and creativity. Particularly with the harmony. Rhythmically too, but jazz is different that way."

Jentsch says for standard big bands, Frank Sinatra records influenced him, and later Ellington, Gil Evans, George Russell and Brookmeyer. "If you've listened to the records you might be suspicious that the range of my influences doesn't really begin and end with jazz big bands. There's a lot of other kinds of influences from all periods of western classical. Renaissance era composers... baroque period composers, like Bach and Handel. People like Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner. Dozens and dozens of great classical composers." Folk music and Indian music also enter into the formula. Also the music Jentsch grew up on: "The Beatles are quite a fundamental influence on my music. Dozens and dozens of rock and pop bands over the years. Guitar players like Jeff Beck, Frank Zappa. All kinds of American blues and the whole history of jazz. So we're talking about a wide range of musical influences. That's not even talking about comic books or novels or movies."

Chris Jentsch leads the Jentsch Group Large

Urie says he leans more to classical than jazz for inspiration. "I'm very much into Kurt Weill. I find his works to be riveting and to this day they still sound completely fresh to me. At the same time, I'm a fan of the French school, the French way of thinking about sonority, with people like Debussy. People like that I find endlessly inspiring. On the jazz side, I love Ornette Coleman and Gil Evans. The pianist on my record, Frank Carlberg, is a wonderful composer. I draw a lot of inspiration from his example... I spent time studying with Vince Mendoza, who is a really great arranger and composer out in L.A., where I'm from. He is the man. I find him endlessly inspiring as well. Every new piece of his I hear I just marvel at."

Adds Schumacher, "Maria Schneider, her use of color and texture. The way she integrates her soloists into the compositions was big for me. Some of the rawness and emotion of Mingus comes into play at times in my music. We were just talking about Kenny Wheeler the other day. His sense of melody. His harmonic sense. That comes into play in my writing. Over time, you go through periods where you're in a zone with particular composer outside of the jazz world. Recently I'm into some of the minimalist stuff. Phillip Glass and people like that who come into play every once in a while."

It's a big musical world out there, with a vast array of sources that can influence today's improvisational music. These composers and many others like them on today's scene don't consider what is "supposed to be" jazz. They are affected by its great masters, but not confined to them.

Another big influence for many young writers in the New York area is the BMI Jazz Composers Workshop, currently directed by Jim McNeely, with people like Mike Holober and Michael Abene in key roles. The workshop was founded by Brookmeyer, composer/educator Manny Albam and author and jazz authority Burt Korall. "It stresses exploration, ranging from the traditional to the new," says its Website. "The techniques that make possible for the composer the execution of thoughts and the development of personal language within the big band setting. Experimentation with form, harmony and orchestration, the solving of performance problems and the need to produce lasting, excellent work are also concerns of the workshop directors."

"It's a class once a week and at the end of every month there's a reading session with a big band," explains Sanford. "All these composers come in and bring their music and look at it, talk about and they get to hear it at the end of the month. It's kind of a breeding ground for young, somewhat experimental composers. Most of the people I know in town that have their own big bands came through that program, at least for a minute. When I was in the BMI workshop Jim McNeely became a really big influence of mine in the way he incorporated this intellectual rhythmic style with a little flavor of humor. I always like that about his writing."

class="f-right">

Getting involved with a large ensemble is a decision that doesn't come lightly. Because of the rigors of the business—unsteady work, high expense—these composers who are still not widely known get involved in other endeavors. Conducting other ensembles. Copying music. Writing or arranging for other groups. Applying for grants.

Rivello, who formed his band in 1993, does freelance arranging and music copy work. He also holds a part-time teaching job at Eastman. Along with running the band, all those functions take up so much time that it's hard to find time to keep up on his instrument, the trumpet. "I miss playing," he notes, "but the trumpet is a very unforgiving instrument. Every time I started to feel like getting in shape (for playing)," work—often with a deadline—turns up in one of his various areas of expertise. "I run out of time in the day."

Rivello, who formed his band in 1993, does freelance arranging and music copy work. He also holds a part-time teaching job at Eastman. Along with running the band, all those functions take up so much time that it's hard to find time to keep up on his instrument, the trumpet. "I miss playing," he notes, "but the trumpet is a very unforgiving instrument. Every time I started to feel like getting in shape (for playing)," work—often with a deadline—turns up in one of his various areas of expertise. "I run out of time in the day."

But the call to lead a band is strong, stemming in part from his grandfather, Tee Ross, who had a big band on the road in the 1940s. "He also had a music store. That's where I started playing trumpet." Ross took the youngster to concerts by Buddy Rich, Maynard Ferguson and Stan Kenton. "Somehow, it's always been in my blood. I just prefer a larger palette... There was never a thought about the issue of money. Just a love for large ensemble and the colors that can be gotten from that.

"When I first heard Thad Jones I went crazy. Then I heard Gil Evans and I went more crazy. Then I heard Brookmeyer and went even more crazy. There's never been a thought about the money thing. That's what I hear as my palette." He had great teachers to help him along from the beginning.

Rivello thought long and hard about the instrumentation he wanted to use, which came out a bit differently. There's tuba and bass clarinet on Facing the Mirror. No alto sax. "I felt I prefer the soprano over the alto sax—although I like alto and certainly write for it—but for my own band, I prefer the sound of the soprano over the alto. And I prefer the sound of the bass clarinet over the baritone sax... So the reeds ended up being soprano, tenor, bass clarinet and they double on flute and clarinet.

"Because of my love for Gil Evans, I wanted a tuba. So I decided on two trombones and tuba. I debated on having a French horn, but decided logistically the two might be hard enough to have, let alone tuba and French horn. Plus, I usually say acoustically, the French horn is blowing the wrong way. So I decided to go with two trumpets and a flugelhorn, and I write for the flugelhorn the way I would write for the French horn. So that part could be transposed and played by a French horn at any point. So I think of the flugelhorn as a French horn that blows forward, sort of."

Facing the Mirror is the first official recording, though Rivello says there is a 45-minute suite recorded years ago that may one day see the light of day for listeners.

"I'm very happy with it," he says of the new recording. "It took a long time to get it to this point. I'm proud and happy about the way it sounds, the way the band played. Everything about it. It's slowly getting good attention. Maria Schneider raved about it. We got good reviews here in Rochester. It's slowly making its way into the world."

In the future, his creative efforts could turn in different directions with different instruments. "I've been thinking for a couple of years, off and on, about putting together an electric version of my band. I'm not exactly sure what that would be yet. That's part of the problem why it hasn't happened...Maybe adding an extra keyboard and a guitarist. Maybe not as many horns. But right now I feel I have more to explore with this (large ensemble). I probably have at least enough new pieces to make two more full CDs. Some of that is more on the edge. It spans a lot of different places. As far as electronic instruments, or world instruments, I still haven't ventured into that world yet. This is really where I still hear things."

class="f-right">

Manricks was in high school in Australia participating in the big band program, where his teacher was American John Hoffman, who had played with Buddy Rich and had some arrangements he used by people like Bill Holman. "So I got into the whole idea of the large ensemble thing from being in a big band myself. It kind of went from there." His grandfather and father were musicians and into jazz. Eventually, Manricks was sent to the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore to study. Being in the U.S. heightened his appetite for jazz. And in Australia, he got to work with people like pianist Mike Nock who was then in the Land Down Under. "He's a serious jazz musician and creative improviser. That was some of my experience down there."

He got more education at the Manhattan School of Music. "I had to do three or four concerts that were large ensemble performances. There were a bunch of composer concerts that I had large ensemble works on. Big band stuff and smaller strong ensembles with a jazz rhythm section. That's when I started learn how to write for strings and started doing that more frequently."

He got more education at the Manhattan School of Music. "I had to do three or four concerts that were large ensemble performances. There were a bunch of composer concerts that I had large ensemble works on. Big band stuff and smaller strong ensembles with a jazz rhythm section. That's when I started learn how to write for strings and started doing that more frequently."

It blossomed into a desire to continue with large ensembles. He experimented with rhythms and harmony in his first creations. On Labyrinth, he took his basic quintet and augmented it with a larger surrounding.

"It was a real expensive album to make. The quintet did one take for everything. Then I did a bunch of woodwind overdubs, up to seven woodwinds. Flute, clarinet, alto flute, bass clarinet. Sometimes I'd have a score for two flutes, two alto flutes and bass clarinet. I overdubbed the woodwind section myself. Then I had an eight-piece string section which I layered four times. So it was like having 28 strings.

"Then I had a French horn player come in and I wrote for four French horns. He led the horns. It was like 62 tracks or something hideous. It was a lot for the guy who was mixing it to bring up on the board. Those orchestra pieces sometimes took an hour to get up in the mixing board. I wanted to get a top-notch engineer to do it because everyone played so beautifully and put so much into the project. I wanted to capture, as much as I could, what actually went down."

Manricks finds it hard to tour with the music, except when played by just the quintet. But he's applying for grants to see if he can get some large ensemble gigs. Also, "There's an orchestra in Finland that is interested. There's a guy in Canada that's interested. And back home in Australia I've got some connections with orchestras, too."

He's proud of his new recording and has already done another for the Posi Tone label to come out at a later date. "A lot of good things have been happening and I think that will continue to happen. I know that I will continue to write for different types of ensembles."

class="f-right">

J.C. Sanford and David Schumacher

Sanford and Schumacher met at the New England Conservatory and have been leading the Sound Assembly for about eight years. "Over a bottle of wine and some chicken stroganoff at my apartment, we decided to take the plunge and start a large ensemble," says Schumacher. "We had a long discussion about our aspirations and goals about writing. Large ensemble was a good place to start for us. We liked the opportunities it was going to present to us as writers. We finished that bottle of wine and came up with a name for the band."

They were both in Boston, but Sanford later moved to New York. "David still lives north of Boston and he just comes down for gigs. We had to split the duties, where I do a lot of the booking and contracting for the players and David does a lot of the other technical things. So it's a good partnership," says Sanford. "We both write in a somewhat orchestral way from time to time. We use lots of woodwind doubles. Using colors is a big part of how we write. You can do that with any sort of ensemble you put together, but a 17-piece big band is the most standard set of those kind of players put together. So, it's a good vehicle for us to expand our palette, but still write something that people can identify with."

Schumacher notes, "There is a lot of room in our music for personality in the individual player. So it's quite interesting to see what each person will bring to the table. It's got that surprise element. You also have guys in the band where you can expect what they will bring and you can design a piece around that player and around their personality. That becomes a great part of the process."

The duo does not write together. The compositions are separate and in concert, the author conducts his own pieces.

"I'm thrilled with how the record turned out," Schumacher says about Edge of Mind. "I feel the players that we had on that session were really able to tap into the meaning behind the pieces and the vibe, to make our writing as effective as it possibly can be. You can put the most amazing piece of music in front of musicians, but if you don't have the right musicians to bring the specific elements and personality to that music, it's not going to go anywhere. It's not going to do anything for you. We had the best combination of players, personalities and music on that session to make it a really effective product. There's a tremendous variety of style and color and mood and emotion on that record. There's a little bit of something for everyone. That's one of the things that make this duo-led ensemble different from some of the other groups around right now.

"If you put on someone else's record, you may love that vibe, or you may not like that vibe," Schumacher said. "But it's that vibe all the way through the record. Whereas out record is constantly this balance between our different approaches. I think in the end it makes for a very good listening experience."

Adds Sanford, "I think as writers, we have a lot of variety within our own music. So it's not just: Here's a David chart and it sounds like this. Here's a JC chart and it sounds like this. All of our tunes on the record have a distinctive sound to them. You can't necessarily say which ones are David's and which ones are mine."

class="f-right">

Jentsch's exposure to big bands also came in school. His is education included the New England Conservatory, Eastman School of Music, and the University of Miami.

"I started writing compositions for small group and became interested in creating more complicated kinds of form. Maybe songs of more than one melody. More substantially written out. Started writing stuff that had more than just guitar, bass, drums, saxophone. Three or four horns. It gets more and more complicated from that. Pretty soon you're studying some of the literature and listening to big bands. Before you know it, you're standing in front of a 17-piece group and they're all looking at your parts, playing the music."

He notes, "It's more a question of adding different things I could do to the overall picture. It wasn't necessarily devoting the rest of my life to large ensemble. It was more like... I do small ensemble stuff, I do classical chamber music stuff, I do lots of different kinds of different musical projects. I was adding this to the mix."

He started the Jentsch Group Large in 2004, got a grant to write a piece from the American Composers Forum and came up with Brooklyn Suite, a 45-minute composition for a 16-piece band. Miami Suite was something written and recorded previously, when he was at school in Miami. While it wasn't done by his current band, it is part of a trilogy of suites he has authored. "I had fun with it when we did the CD release for Brooklyn Suite in New York. I sort of re-edited it a little bit and we performed both suites at that concert. I was able to bring the initial suite of the trilogy into the new era, so to speak, by having the same band play the first two suites when I completed the recording for the second one."

He started the Jentsch Group Large in 2004, got a grant to write a piece from the American Composers Forum and came up with Brooklyn Suite, a 45-minute composition for a 16-piece band. Miami Suite was something written and recorded previously, when he was at school in Miami. While it wasn't done by his current band, it is part of a trilogy of suites he has authored. "I had fun with it when we did the CD release for Brooklyn Suite in New York. I sort of re-edited it a little bit and we performed both suites at that concert. I was able to bring the initial suite of the trilogy into the new era, so to speak, by having the same band play the first two suites when I completed the recording for the second one."

With the large ensemble being financially prohibitive, Jentsch applies for grants to help out. Some of the cost of Cycles Suite was defrayed by a New York State Council on the Arts grant. "To some extent, with these huge projects, it's a little bit about if I have some extra money, or if I've gotten a grant to do it. I kind of look at it that way." In fact, "the biggest way the economic downturn might affect me is that grant organizations aren't getting as much funding. They're going to be giving out less grants. That's problematic."

Jentsch is pleased with the new recording, but is already looking ahead at new fields to plow.

"If I was to do another large ensemble project, I think I'd do something very different that these large suite things I've been doing now for 10 years or so. The next thing would probably be separate compositions, so that I can experiment with different sort of vibes and not have to worry about how it relates to the larger piece as a whole and not have to work so hard at connecting the things together. I'd like to write a set of compositions that work well as a CD, but don't have to flow all one into the next. And maybe get some radio play at the same time. Radio is understandably reticent to play the whole thing or even excerpts of suites. They don't realize each movement can live on its own."

Regarding today's composers and how he looks at future projects, Jentsch says composers "are not afraid to be inclusive with their definition of jazz, as opposed to exclusive. It's like: what will I put into the mix, rather than what I will exclude from the mix. I'll put almost anything in. It doesn't matter where it came from. Sometimes people call it an eclectic approach. I kid around and call it a hopelessly eclectic."

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.