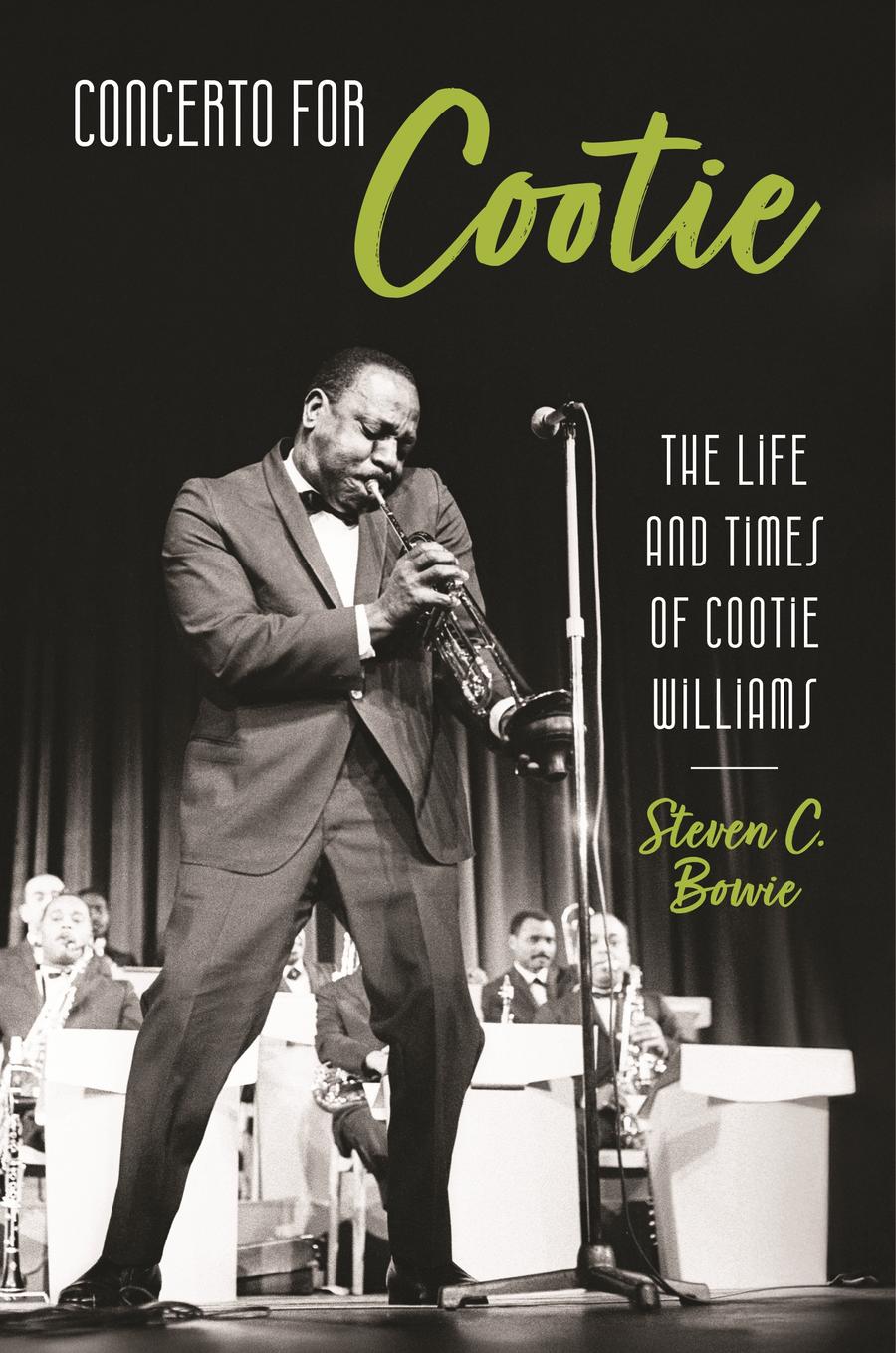

Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Concerto for Cootie. The Life and Times of Cootie Williams

Concerto for Cootie. The Life and Times of Cootie Williams

Cootie Williams is not in the Down Beat Hall of Fame and is largely remembered only in the context of Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra

—Steven C. Bowie

Cootie. The Life and Times of Cootie Williams

Cootie. The Life and Times of Cootie Williams Steven C. Bowie

443 Pages

ISBN: #9781496859440

University Press of Mississippi

2025

Benny Goodman, who had employed Harry James and Ziggy Elman in his nonpareil 1937 trumpet section, preferred trumpeter Cootie Williams to them, admiring his "unlimited power." Williams had come up with Chick Webb and Fletcher Henderson. When he left Duke Ellington to join Goodman, it was big news, both for Ellington and for Goodman fans alike. And yet his name is mostly known now to cognoscenti, trumpet players included. He was Charles Melvin "Cootie" Williams.

This much-deserved biography by Steven C. Bowie is a good read. It is lengthy, but the story is in the telling. Musically sophisticated, it is not overburdened with technical matters. Yes, Williams was a player associated with "effects" such as growling, vocalizing, and the sophisticated practices of plunger mutes. But with an open horn, his tone had the purity, presence, and projection of a classic lead. Williams was a "player's player," if ever there was one. He may well have been too versatile, and therefore hard to pigeonhole, because he moved easily between styles. Despite the grandeur of his recordings of "Echoes of Harlem" (1936) and "Concerto for Cootie" (1939), he never reached the stature of Louis Armstrong, whose work profoundly influenced him. In fact, Williams recorded a lovely version of Armstrong's iconic "West End Blues." Significantly, no Armstrong recording of one of Cootie's classics seems to exist, although, of course, Armstrong was a different style of player.

Growing up in Mobile, Alabama, Williams was something of a prodigy. He already had a substantial name by the time he joined Ellington. While ultimately and inevitably associated with Ellington, this experience does not seem to have been an altogether satisfactory one. Ellington's bands were notoriously undisciplined, and Williams, a serious taskmaster himself, took over a role of disciplinarian. Jimmy Maxwell, another storied lead trumpet, tried out Ellington for a while. He later observed he could have never put up with the disorganization that Williams endured. At some level, Ellington must have sensed Williams' unhappiness, especially considering the increasing solo time that Ellington afforded Rex Stewart, whose flash inevitably exceeded his substance. So, when Williams left for Goodman in 1940 and Ellington made no attempt to keep him, over a trivial sum, $25 a week (hardly trivial in today's dollars) Williams was deeply wounded. He was replaced by Ray Nance, an excellent player, and a fine musician, but scarcely in Williams' league as far as the horn went. Ironically, Williams seems to have been one of the few musicians who genuinely enjoyed working with Goodman. There were no horror stories, just a great deal of mutual respect. Williams thought he would be better able to play the sort of music he wanted to play with Goodman. The imprimatur of a famous white band in Jim Crow America did not hurt either, although playing with Goodman did not boost Wiliams' career as much as it did, say, Harry James.' In the parlance of the day, Williams was a "sepia" player and nothing was going to change the racial outlook of Americans, talent notwithstanding.

After Goodman, Williams had his own band, which brought new talent like Bud Powell and Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson to public attention, premiered "Round Midnight" (1944), toured extensively with Ella Fitzgerald and the The Ink Spots, and even continued formal study of the trumpet. He was financially successful, although the big bands began to implode due to post-war economic adjustment and the burgeoning influence of small, bop oriented bands.

He tried to navigate swing to bop. Highly regarded as a trumpet player, his success as an artist was less obvious. Later critics like Gunther Schuller, tended unfairly to dismiss him as inconsequential. And that is really the relevant issue: no one questioned Williams' ability, but his place in the hierarchy of jazz trumpet players seems less secure. Of course, the biography is full of rapturous reviews, and no surprise. His peers, including Armstrong, James, even the "obscure" Randy Brooks, knew just how accomplished Williams was. Was it his affect? Sometimes deadpan, Williams was no stranger to showmanship, or to what was called "race" behavior. His recording contracts, even with Capitol, never seemed to produce much. His big band got mixed reviews, not so much for musicianship as for choice of material. As Steven C. Bowie writes, "Cootie Williams is not in the Down Beat Hall of Fame and is largely remembered only in the context of Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra." And, probably most crucially, "unlike Ellington, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Lionel Hampton and Armstrong, Cootie was not able to cross over to the white market." Exactly why this was so remains unclear. Perhaps Bowie's biography will repair some of the neglect of Williams that the dismal history of American race relations has produced. Yet there seems little prospect of it: Williams was an artefact of a different time and a different society. As even he learned, you cannot go home again when he returned to Ellington. Alas, novelty in jazz is often regarded as a virtue itself. Too bad.

Tags

Book Review

Richard J Salvucci

University Press of Mississippi

Benny Goodman

Harry James

Ziggy Elman

Chick Webb

Fletcher Henderson

duke ellington

Louis Armstrong

Jimmy Maxwell

Rex Stewart

Ray Nance

Bud Powell

Eddie Vinson

Ella Fitzgerald

Ink Spots

Gunther Schuller

Randy Brooks

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.