Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Bertram Turetzky: Contrabass Pioneer

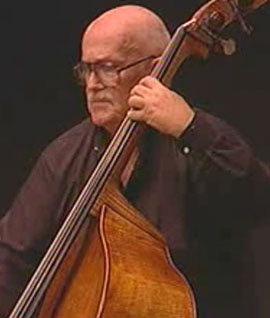

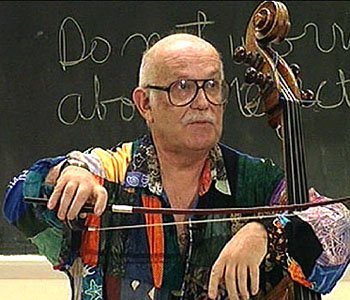

Bertram Turetzky: Contrabass Pioneer

The lazy guys who play just like they did twenty years ago, don't interest me much. I like the guys who are always moving forward, always trying something new.

It is, perhaps, as a teacher that he is most revered. One way of measuring a teacher's importance is by the success of his former students. Turetzky's record in this regard is almost unbelievable. One of his student's, Manfred Hecking, plays in the prestigious Vienna Philharmonic. The winner of the Thelonious Monk 2009 Bass Competition, Joey Johnson is a former pupil. John Leftwich, who went on to play with Carmen McRae, and Rickie Lee Jones studied with him, as did virtuosos Mark Dresser, and Bob Magnusson. He took a young, raw bassist who sang, Kristin Korb, and opened doors for her. Perhaps his most famous student is bassist Nathan East, (Fourplay, Eric Clapton, Phil Collins). East got an offer from John McLaughlin to join his "One Truth Band" in the 1970's. He turned down the offer to finish his studies at U.C.S.D. with Turetzky.

Even before his career in classical music, Turetzky loved jazz. His depth of experience in the many genres that define the idiom is likewise astonishing. As a young Jewish kid, he jammed with black Swing-era stars in the 1950s—playing, to this day, with an Ellington repertory band. Charles Mingus accepted him as a student, (though Turetzky backed out). When playing mainstream jazz, Turetzky's sound, time and ideas are totally authentic. He plays with a full, dark, acoustic sound that is reflective of players like Mingus and Ray Brown (two of his favorites), while maintaining his own distinctive identity.

One of Turetzky's defining characteristics is his creation of what are known as extended-techniques. You could say that he wrote the book on extended contrabass techniques—literally. His master edition of these ideas, The Contemporary Contrabass (University of California Press, 1974), is still the standard practicum for both virtuoso bass studies, and a kind of cookbook for New Music composers. Indeed, many of those 300 commissions were written for him after composers got a look at what the bass was capable of.

Turetzky was playing world music at least 30 years before anyone thought of calling it that. Turetzky's vast experience in all of these other fields informs his masterful work as a free improviser. He has recorded many albums for multi-instrumentalist Vinny Golia's Nine Winds Records, often with Golia himself. Likewise the Israeli record label Kadima Collective Recordings has begun to feature him, most recently on Triangulation II (2010), with Golia and trombonist extraordinaire George Lewis.

Despite having the distinction of being one of the most recorded contrabassist's in America, Turetzky isn't even thinking about resting on his laurels. He's got a restless, inquisitive muse, is looking forward to projects with Anthony Braxton and Bobby Bradford, and has begun writing his autobiography.

Chapter Index

- I'm Still Around. The Early Years

- Hartford Jazz Scene

- New York Reconnaissance / Meeting Mingus

- Lack Of Classical Bass Repertoire

- New York Debut

- Moving to California. U.C.S.D.

- Stellar Students

- Amplifiers. Solid Body Versus Acoustic Basses

- Peers and Contemporaries

- Vinny Golia, George Lewis and the Future

I'm Still Around. The Early Years

All About Jazz: I know from talking to you earlier that you are interested and eager to let people know what you're doing now.

Bertram Turetzky: Well, yeah; you know, I was born in 1933, I'm 77, and people say "Well you don't go downtown any more, you pick and choose your gigs" and I don't travel much anymore, I don't enjoy that so much, plus there's always the issue of are they going to have an instrument that speaks to me, so that I can do my very best, because you know, it's important to always do your very best. So yeah, people ask, "Is he still around?," I'm thinking about putting out a CD, and calling it I'm Still Around.

AAJ: Not dead yet...

BT: [Laughter]...not dead yet.

AAJ: Let's start at the beginning, you were born in...

BT: I was born in Norwich, Connecticut. It's south of Hartford. It was an old river port, and it came up from the river shaped like a rose, so it is "The Rose" of Connecticut. It was the place that the Mohican Indians roamed. As a little boy, there was a library at the corner of Broadway and Rose and they had a lot of books about American Folklore and, as I kid, I used to love reading books about the west and these American heroes like Paul Bunyan and Cochise and Crazy Horse. I was there recently and it brought back all of those memories.

AAJ: So, growing up, why music?

BT: That's a good question. There was no music in the family, we've been going back, trying to find it, there might have been a cantor way back. My father was a business man, he was ah, not very, no he was successful, he just didn't like it very much, and my mother was from that area between Russia and Eastern Europe. They discovered when I was 5 years old that I'm a bronchial asthmatic, so I spent a lot of winters in the hospital. So, when you're in the hospital, what are you going to do? You can't run around, you can't play games, in those days, there was no television. So I began to be a speed reader, and one of those writers I really liked was Mark Twain, and in Twain's writing, there are all these references to the banjo, and I thought, "What is a banjo?" I looked it up and saw what it was, and one day in grammar school, a note came around offering music lessons—one of the instruments being taught was the banjo. So my dad shelled out 35 bucks for a banjo...

So, I also played with some of the people from high school in my same socio- economic background as me, so that was one group, in fact that was the Jewish group...you see culturally, I lived in a bubble, you know, an orthodox Jewish house, everything was done that way, you know my grandmother never ate dinner with us, everything was proscribed in a certain way, so we ate Kosher foods you see, I never had a hamburger till I was in college, unless my mother made it with chopped Kosher meat.

So, I had those guys and I had the older musicians and I had friends, one of whom was an older black guy who played boogie-woogie piano and I jammed with him. So I started to really enjoy playing, and then, I started to hear jazz music, and that was it for me. And the instrument that did it was the bass, because you know, Robert, that the bass is the glue between the rhythm and the harmony. And I remember, it's like holding everything together, it's like Atlas holding up the world.

AAJ: Do you remember your first bass?

BT: Oh yes, I do. I don't remember exactly how old I was, but it was fifty dollars. I've traced that bass for a while because it stayed in CT. and when I sold it, I sold it for more, and it got bought and sold by various people until it was worth several thousand dollars at a certain point. I mean, I didn't try to make money at it—I'm not a business man, I consider myself an artist and a student, and a teacher.

So, anyway, I got a teacher and started to learn, and at age sixteen, I'm learning to drive and driving down the Connecticut shore, me and the guy who is teaching me and we run out of gas. A couple stopped, and their name was Ed and Val Owens, which I still remember. My friend Bob, who I was with, said, "Yeah, if you'll give me a ride to get gas, he'll stay behind, because all he does is talk about jazz. He is starting to drive me crazy !" And they said , "Good—because that's all we talk about, too!"

So they came back and said, "We have a friend, Eugene Sedric who's coming to visit next weekend, you should come over and bring your instrument." That Eugene Sedric was the clarinetist for the Fats Waller band. He was from St. Louis and was called "Honeybear," and he was a sweetheart of a guy. So I came down there on Saturday with my guitar and a fake-book and he played and improvised, and I played and improvised, and afterwards he said nice things and then he asked if I played the bass too, and I said yes. He told me he had a gig the next week on the shore, and he said, "Maybe you'll come and play with us, would you like to do that?" and I said, "Well, sure."

And I did that quite a few times—he would bring a lot of the old black swing stars, and they were all very nice to me. They gave me advice like when playing with the trombone, stay out of his register, when playing with the clarinet, do something different. It was just like orchestrating, but they didn't call it that. So, at that point, the bass sort of took over my life.

Hartford Jazz Scene

Hartford Jazz Scene AAJ: You've said, in earlier interviews, that the prevalence of drugs in the jazz culture scared you away from pursuing jazz as a career. Is that what led you into the world of classical music?

BT: I was in music school around 1951, 1952, and I wanted to be a jazz musician. So I began meeting the guys in the jazz world, and, again there were different groups. There were the black guys who played in the north end, and I used to go and sit in with them. And they were all very good to me.

The one thing I learned from them was, if you are in a black club and a black woman comes up to you—stay on the bandstand. Don't go sit with her, because if you do, you're going to start trouble. If a [black] woman comes up and says she likes your playing, say "Thank you very much," but stay on the bandstand.

AAJ: Was that hard sometimes, staying on the bandstand?

BT: Oh yes, of course it was. But I didn't want to get beat up; I wanted to be invited to be there. I didn't want to be an interloper. So, I treated them with respect, and they treated me with respect. One summer, I filled in for a black bassist at that club—it was an Elks Club—we called it the "Black-Elks Club." It worked out good, and, I began to play with "the cats." I learned stuff; I had a couple of epiphanies along the way.

The first week of music school, I didn't feel comfortable, and someone said there is a jam session that I should go to. So anyway, the pianist at that moment was Jack Elliot, who went on to be a big arranger in Hollywood, you know, "Barney Miller" and a lot of things on television. So the saxophonist calls, "Body and Soul," and he says "five-down" [five flats]. I barely know the tune, so I figure I'll play a D flat, and the pianist plays E-flat minor ninth, and the saxophonist looked at me sort of like, "nice— you dumb kid," but it wasn't nasty, I always appreciated that about him.

He was the leader of the Mancini Institute for many years, and one day when I was there, I told him that story and he collapsed laughing. So, that was an epiphany: I thought, "There's a certain way to approach this music, and I'm not doing it right."

So I bought myself a fake book, and I looked at "Body and Soul" and realized how bad I missed it, and I began studying those tunes. I began to get serious. I call that, "jazz craft." I was in school, and I learned, music theory and classical music history and all of that, but there was a parallel school—very informal, but the guys who were into jazz, we began to get together, and discuss the latest records and the news of what was happening, and stuff like "Philly Joe [Jones] was playing soft last night." So all the cats had to play soft because Philly Joe was; Philly Joe was where it was at.

So I began to learn more about the music. Prior to that I was an "ear guy." Duke Ellington used to call them "ear cats." I have no idea what I was doing on the guitar before that. It was probably very free-form. But they put up with me, and at school I tried to figure out, did they need a bassist; did they like me; what was hip—and I started to play with all these guys.

Anyway, I started playing in a neighborhood that was sort of a dangerous neighborhood—it was black and Puerto Rican, it was formerly Jewish but the Jews moved out. It had this club where we could play... so here's the other epiphany: I'm playing there and playing pretty well, and when the set was over, I'm sitting down, and this very pretty girl come up to me, and says "Man, you were playing your ass off!." Now, I'm leading this sheltered life, I had never heard a girl say "ass" before. She said, "Would you like to go for a drink?" I was a small-town kid, women weren't that forward.

She was from Hartford, capital of Connecticut. So I said yes, and started to hang out with her, have fun with her, for awhile, then someone said "Hey—are you seeing Judy?" I said yeah, we're having fun. He asked if I knew anything about her, and I said no. He then told me that Judy had a thirty-five dollar a day "habit," and that she supported that habit by being a hooker! He told me "Stay away from her—you're a good kid, I don't want to see you get in trouble."

So that scared the hell out of me and I began seeing guys go out for a little "J" now and then, and that didn't bother me, but she was involved with smack and that scared me. I was very naive; I had no idea till then what she was up to. And, so I thought, "Do I want to be around these people all of my life? No." I loved the music, loved the players, but the scene—I didn't like.

New York Reconnaissance / Meeting Mingus

New York Reconnaissance / Meeting Mingus BT: So, about the same time, I went to New York with a trio with Dave MacKay and Joe Porcaro. We went to audition for this agent. Dave also sang some beautiful tunes, and the agent says, "You guys are terrific! Which one of you does the comedy?" Well, we didn't do comedy. He asked if we had a chick singer with a strap-less gown, or a tenor player who could "Walk-the-bar," and we said "No. We just want to play good music."

The guys says, "Well, look. We can book you year-round playing Holiday Inns all over America. You could each make two hundred dollars a week. Is that what you want to do?" We said, "No, thank you." It was a good reality check. We went home sadder, but wiser.

So there were two brothers who played violin and trombone, the Landerman brothers, and I got recommended to them, and I played with them for several years. They had the big theater in Hartford, the Bushnell, and I began playing there. It seated 3800 or 4800 people, and I began to be the show bassist there.

So, I figure I can do better in the symphonic world and the show world and the commercial music world. So, all these things fell into place. I met my wife and, in 1959, we got married. I could help her go to school, because I had money coming in, because I learned to become a professional musician. I still loved jazz, and I played when I could, but I didn't hang out—that wasn't such a big thing anymore.

I went to New York again, after the audition. I wanted to do a reconnaissance, so I went to a club, The Royal Roost. There was a quartet there, with Buddy Rich, who was fantastic, I never heard anybody like that before. The bassist was, eh, a "B-flat bassist. I thought, "I could do that." I couldn't really, but I thought I could. I couldn't play those tempos; I didn't know all of the tunes. The guy might have been a junkie, and he was "B-flat," but he was okay.

Then I went to another place, and I heard George Duvivier playing, and he had perfect time. Perfect time. And I thought, "No, I can't do that." He had a beautiful sound, beautiful pitch, lovely time.

And then, I heard my main guy, Charles Mingus, play. I approached him about taking lessons, I was still...I had one foot in the concert world and the commercial world, and one foot that didn't know what to do. So, he interviewed me outside the club, it was winter, very cold, and asked me a lot of questions: "How much counter-point have you had? How much harmony?," you know. Then he said, "O.k., you can have lessons." Then, I heard that he had smacked one of his students in the chops, and that he could be quite "physical." So I thought, maybe I could study with him from afar.

So I would go to New York to clubs and learn what I could. My wife, Nancy, got a big kick out of it, because she said, "You know him, right, we should sit up front." I said, "No, we'll sit in the back, you'll see why." So Dannie Richmond was his drummer, you know, through thick and thin, Mingus got mad, and grabbed his ride cymbal, picked it up, and threw it at him. He pulled Booker Little's trumpet right out of his mouth for playing something wrong.

And Eric Dolphy was on the other side of the stage—he just smiled at him. Mingus knew that Eric always carried a knife in his pocket and if he fucked with him, he was gonna get cut. Charles McPherson told me he would always stand on the opposite side of the stage, because Mingus was not always in control.

Then later, much later, I recorded the "Goodbye, Pork Pie Hat," Lester Young's requiem, and I sent it Atlantic Records. Ilhan Mimaroglu was my contact there, and he told Mingus, "There's a bassist from California, and he recorded 'Goodbye Pork Pie Hat' in four tracks." "[overdubs]," Mingus said, "Yeah? It's a saxophone piece. What's he doing it on the bass for?" Mimaroglu said, "Charles, I'd really appreciate it if you came down and heard it, I think it's really good." So, he made an appointment, came down, heard it and said, "Well, he's classical, you know, that cat can play." So, he heard that I had studied him from afar, and he liked my work, so that was a big affirmation.

AAJ: So, you never went for one-on-one lessons with him?

BT: Never. I went to New York several times to hear him, and I listened to all of his recordings. The point is, I got out of my bubble, I didn't have to eat Kosher anymore, I saw girls that were not Jewish, I got more ecumenical as I went along. But the drug thing turned me off. My mother, who had walked across Europe from Poland, that was the last passport, to Marseilles, France, to come to America, and she was very concerned about security, you know, "How can you make a living playing music?"

When I was at music school and would come home to do a gig, she would say, "Well Mrs. So-and-so says you are playing music." That didn't sound right to her. So finally I told her to tell Mrs. So-and-so that I was concertizing, [laughs] that sounded better to her. So, anyway, things started to come together, I started to play some chamber music, and I started making some arrangements of classical music so that the bass could be heard, because, I wanted to play, man.

So the first guy I met when I came to music school, his name was Nicholas, and he was a composer and, he went overseas to, he got a fellowship to study in Italy, with [Goffredo] Petrassi, and somebody said, "Nicholas committed suicide." Well, now that I'm a little older, and lost some former students, and outlived many of my contemporaries, I'm a little more relaxed about death, I see that we live and we die. But, it upset me then. So, I put in a call to his parents, and I found out that he had some pieces with the bass, and, to make a long story short, we put on a concert and played one of the pieces, and it was a big success, and his parents were there.

They didn't speak English, but through his sister, they said that they were really glad to hear it because they had no idea their son was such a poet. Then I realized that maybe this is what's happening: composers write music, and often times nobody wants to play it; sometimes players, (especially bass players) don't have much music to play. So maybe we could come together.

Lack Of Classical Bass Repertoire

Lack Of Classical Bass Repertoire BT: So I was thinking about developing the solo bass repertoire, and people said, "Well, if you want to get a lot of pieces, you got pay a lot of money to get commissions." I said, "I don't have any money. I have children." So, I started looking at the bass, and I thought, "This is a big instrument. It can do more than a lot of people think it can." So, I looked at pizzicato technique and I found that by using my thumb instead of my fingers, I could get a guitar effect.

When I played with the Greek band, their big instrument was the bouzuki . I learned how to do a fast pizzicato with two fingers to approximate that sound. I was invited to Wesleyan University. They had a big Indian music program and I heard this fantastic sitar player and I thought, "I've got to learn to do some of that." I found I could use the D string as a drone, and then do hammer-ons on the G string to get that sound. And I began to go around, to show composers these different things I could do on the bass. Some of them began writing pieces for me.

AAJ: So, the development of all of these extended techniques, which you codified in The Contemporary Contrabass went hand-in-hand with attracting composers to write for you?

BT: That's exactly right. How else was I going to get a piece if I didn't have any money?

AAJ: You were playing in the symphony at that time?

BT: I was playing in several symphonies. Finally, I got good enough; I'm trying to remember what year, certainly in the 1950s, to play in the Hartford Symphony, which worked out very well for me.

AAJ: When did you become the principal bassist?

BT: I only became principal occasionally. I became assistant principal on the first chair after awhile. What happened was, I formed a chamber group called the Hartt Chamber Players, because that was the name of the music school I attended. We had this chamber group and we did a summer series, playing in libraries around town, playing throughout New England, and one day, one of the angels of the symphony, this very rich insurance man, his name was Francis Goodwin II, I think. He heard me play an arrangement of Richard Strauss' "Til Eulenspiegel" for five pieces, and it was a tour-de-force, you know, a real hot arrangement. He heard it, and he was obviously real impressed because he called the symphony and asked, "Why is Mr. Turetzky in the back of the bass section and not in the front?"

So, suddenly, I was called by the Union, and I had an audition for assistant principal bass. I found out, later, that Mr. Goodwin had arranged for that. So I have the audition which was fun, because the other bassist auditioning was the principal bassist's son. And I won the audition.

Anyway, all the symphony work started to take time away from other things. There's just a couple of things I'll talk about very briefly: a lot of classical music to me is all about ego. I don't like ego. I think if you study the history of the world, you'll find that ego gets us into a lot of trouble. So, I started liking music that's more democratic.

I always liked spending time in libraries. In the music library at music school, I started to find a lot of early music, pre-Bach. So I'm getting into that field, a lot of things are happening, I've got the chamber group, I play in New York occasionally, playing in festivals. Then in 1959, I think it was, Bill Sydeman wrote a piece called, "For Double Bass Alone." It was an unaccompanied bass piece. Well, for a string player, working without a piano, you really up there without any clothes on. Without a net. You've got to do it, though. That's why the unaccompanied Bach cello pieces are fabulous pieces.

So, [oboist] Josef Marx calls me and says, "There's going to be a concert in 1960 at the Greenwich House for the Festival Of American Music, and it's going to be on WNYC and I think it would be a good idea if you played the Sydeman piece there." I said, "I'm on. I'm there." There was no talk about money, I just know I have to play, and I figured, if you want to make it, if you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere, like the song goes.

So, [oboist] Josef Marx calls me and says, "There's going to be a concert in 1960 at the Greenwich House for the Festival Of American Music, and it's going to be on WNYC and I think it would be a good idea if you played the Sydeman piece there." I said, "I'm on. I'm there." There was no talk about money, I just know I have to play, and I figured, if you want to make it, if you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere, like the song goes. So, David Tudor, the pianist who was associated with John Cage was backstage, and he played a piece with the violin, a wonderful piece that I later played with the violin several times. David, was very nice to me, he knew I was very nervous. So I walk out on stage, and Edgard Varese is in the audience looking at me. And it scared the hell out of me. I mean, I was beginning to have a career, I was playing in New England and New York, and it was very intense. I had a recording of his music with "Octandre" on it, which I later played for him—but it shook me up a little bit.

Well, the performance went. I had fears at first, but I pulled it off. It had a lot of energy, and Varese came and shook my hand, and I met some other people, and it was beginning to happen. I met Ralph Shapey who was there, and he wrote a piece for me, and in 1960 I played in The Music Of Our Time, which was a very big series, it was at the 92nd St Y, and everybody was there.

Every time you play a contemporary piece composers are there, and if they think you're good they say, "I have a piece for the bass." Or, "I'd love to write a piece for you." And so it started. Did I plan it to happen that way? A little bit, a little bit. I always say it was an improvisation. I wrote letters to composers asking, "Do you have a piece for the bass?" And when I married Nancy, she typed them out, we got lists of composers. I mean we really went at it; I wanted to have a career.

But with the symphony, if the conductor got lost, they'd blame the bassists. The bassists are always too loud. The only symphony that doesn't get any shit like that is the Vienna Philharmonic, and I have a former student who plays there. I went to two parties there and they said, "No conductor ever tells us to play softer. So, I met Henry Cowell, I met Stefan Volpe.

AAJ: You started playing what we now call world music around that time, correct?

BT: Well, I was developing a career as a soloist and with chamber music, but I had to stay in the orchestra, because at a certain point, kids came along. One night in the symphony, a sort of darker skinned guy than me came over, and he was dressed in a tuxedo, and he asked me if I was Bert Turetzky, and if I could play in 5/8 and 7/8, and I said, "Yeah, why do you ask?"

He said he had a Greek band, and that was the kind of meters they played. He said he needed a bassist, and I said, "Well, my wife said she's pregnant this morning. Do you pay a lot of money?" They paid double scale. So I became a Greek musician. One day we're playing and one of the musicians started speaking Greek to me .

So, what I'm telling you is that I played Polish music, I played Greek music, I played Klezmer music, I played Italian music. When I read biographies of musicians, I don't see anyone with that kind of background; you see, that's why I say I'm blessed. People ask somebody like Vinny Golia, why does he like to play with Turetzky, and he says, "Well, he's got all kinds of stuff; he's not the typical free jazz player. He's got waves of stuff."

Jim Hall was there, Richard Davis was there. Richard Davis studied with David Walter, my bass teacher at the time. Jim Hall was a friend of Don Erb, I played a composition by Don Erb, so he came to see his friend, hear his piece.

Jim Hall was there, Richard Davis was there. Richard Davis studied with David Walter, my bass teacher at the time. Jim Hall was a friend of Don Erb, I played a composition by Don Erb, so he came to see his friend, hear his piece. Oh, on the way down, Nancy forgot, or I forgot, to pack my tuxedo pants, so I'm wearing a five dollar pair of black chino pants with my tuxedo. My wife gave me a kiss on the cheek before I went out, so I've got red lipstick all over my face, I mean I really look like a clown out there.

So I went onstage and took a bow, and start to play the unaccompanied bass piece, and, I'm going to start with an up-bow, which is very difficult to control, and I look into the audience and several of my friends are starting to cringe. Well, I made it work and the composer of the piece is thrilled. Fred Zimmerman, the great bass teacher from Julliard and the New York Philharmonic, is there, with 25 of his students, and he liked it very much, which was important. He and I became good friends.

Well, we stayed up all night to read the reviews in the morning, and the reviews were very good. I was considered to be quite a success. I never really thought, what would happen to my career if I had gotten bad reviews, you know. My teaching position at the school, my job with the symphony. I didn't realize what a chance I was taking [laughs].

AAJ: You were ready though, right?

BT: I was ready. I was ready, and it was a good, an interesting program. I had a piece with bass and vibraphone, and a piece with a bass and flute that I played with Nancy that went swimmingly, the electronic piece. Then we did a piece with saxophone, alto flute, percussion, bass, soprano and a narrator off-stage who spoke many languages, so it was really quite stunning.

So, then things started coming around, we had two boys by then, (who have done very well for themselves. We're very proud of all of our children), and, more records came, people wanted me to do this, do that. But, there were economic problems. Between the school and the symphony, I was making a decent living, but I was always running, running. When I wasn't running, I had commercial work to do.

So, one of the people who I had wrote to early on said he was writing a piece that the bass would figure in quite prominently . So the International Society for Contemporary Music was putting on a concert and they were going to feature this piece of music. The guy's name was Robert Erickson, and he became one of the first professors at UCSD. He wrote me and said, you should really be out in California, he could get me a half- time job at Mills College [Bay Area]. I said, "I've got two kids. I couldn't do that."

< Previous

The Perperikon Suite

Next >

Optical Delusions

Comments

About Bertram Turetzky

Instrument: Bass, acoustic

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

Bertram Turetzky

Interview

Robert Bush

United States

Ornette Coleman

Richard Davis

Joe Johnson

Carmen McRae

Mark Dresser

Bob Magnusson

Kristin Korb

Nathan East

Fourplay

john mclaughlin

Charles Mingus

Ray Brown

Vinny Golia

George Lewis

anthony braxton

Bobby Bradford

Fats Waller

Dave MacKay

Buddy Rich

George Duvivier

Dannie Richmond

Eric Dolphy

Charles McPherson

Lester Young

Jim Hall

Jimi Hendrix

Rob Thorsen

Gunnar Biggs

Peter Sprague

Albert Stinson

Charlie Haden

Michael Moore

Edgar Meyer

Gary Peacock

barry guy

Dave Holland

Barry Altschul

Chick Corea

William Parker

Cecil Taylor

Ron Carter

Tony Ortega

Joelle Leandre

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.