Home » Jazz Articles » The Jazz Life » Songbirds: An Interview with Singer Judy Niemack

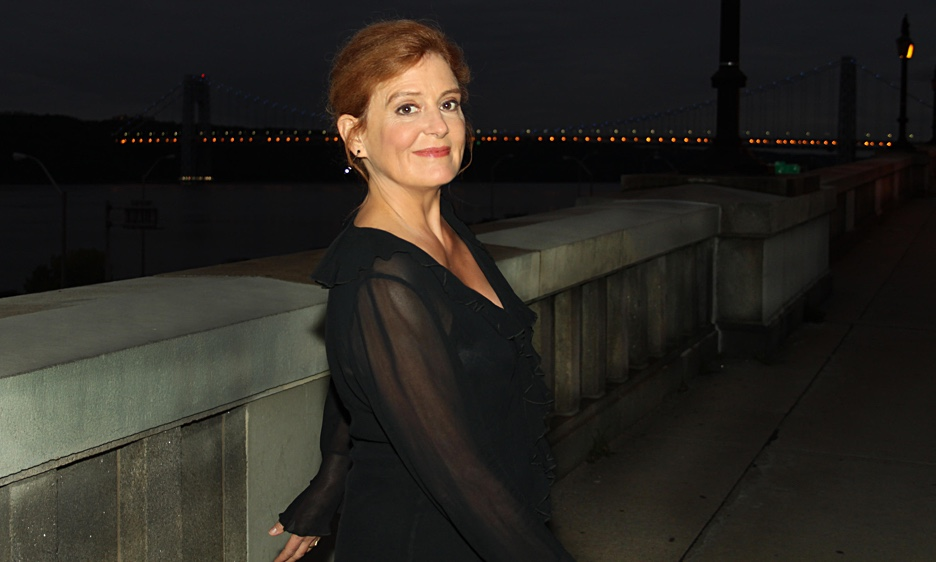

Songbirds: An Interview with Singer Judy Niemack

Courtesy Janis Wilkins

I just wanted to do everything. I was just like, give it all to me. I want to do all kinds of vocal music! And I was transcribing all the vocal solos I could find. And there weren't many...

—Judy Niemack

But you'd be wrong.

Both have a classical music background, Clayton at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, before moving to New York City in 1963, and Niemack, who studied Bel Canto singing for three years when a teenager living in Pasadena, Ca., and then jazz improvisation with saxophonists Warne Marsh, an acolyte of Lennie Tristano, and Gary Foster, before going to the New England Conservatory and Cleveland Institute of Music. Her first major engagement after she moved to New York City in 1977 was a week at the Village Vanguard singing in Marsh's band. In 1992, Niemack moved to Brussels and taught vocal jazz in the Royal Conservatory of Brussels, the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp, and the Royal Conservatory of the Hague. In 1995, she moved to Berlin, where she became the first Professor of Jazz Voice in Germany, teaching at the Hochschule für Musik "Hanns Eisler" (later called Jazz Institut Berlin), and in 2003 also established the vocal jazz program at Musikene, the Basque School of Higher Music, in San Sebastian, Spain. Niemack has written lyrics for over 100 compositions by Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans, Pat Metheny, and Kenny Dorham (among others) which have been recorded on numerous albums.

Clayton is known for her vocal work in the early 1960s while in her twenties, and was championed by bassist and composer Charles Mingus, and minimalist composer Steve Reich. She is known primarily as a spontaneously improvising singer, often in the free jazz and avant-garde music arenas, with a signature singing style that demonstrates her remarkable vocal range, impromptu poetry and spoken word riffing, and, more recently, using looping and other electronic effects in her live performances.

It's the two singers' mutual love of the purity of improvisation, where it becomes more obvious what they have in common. Tristano's band with Warne Marsh and Lee Konitz was the first jazz group to record and perform what became known as Free Jazz, back in the late 1940s, an art form of which Clayton has become a Maestra. It would take another 10 or so years before the music scene, and players like Archie Shepp and Ornette Coleman, successfully explored what Tristano, Marsh, and Konitz started.

What Marsh learned at Tristano's knee, and passed along to his students, was the beauty and purity of improvisation, particularly the long line and the avoidance of licks and sentimental string tugging. To him and his students, such as Niemack, there is a true distinction between sentimentality and emotion, which is a bit like comparing fast food eating to fine dining.

In mid-2023, Clayton and Niemack released an album of duos, trios and quartet recordings featuring themselves and a rhythm section that highlights not only what they are both well known for—their mastery in interpreting jazz standards, but also Niemack's ability to write new lyrics for instrumental jazz tunes, and Clayton's still remarkable vocal abilities. (Judy Niemack -Jay Clayton: Voices in Flight)

In an interview in August, 2023, Niemack talked about the record and her career.

All About Jazz: When did you and Clayton first meet?

Judy Niemack: I met Jay in 1979 through Cobi Narita, an important person on the scene then and a producer. She started the New York Women's Jazz Festival, the first all-female jazz festival in New York City, which later became the International Women's Jazz Festival. And Jay was working with Cobi to produce that festival. They had people like Amina Claudine Myers and JoAnne Brackeen and other female jazz artists of that time. This was revolutionary back then, right? Cobi is a Japanese "jazz angel" who I think has to be around 95 now or something, and she was married to Paul Ash, who had this big music store on west 52nd street in Manhattan. They produced concerts together and helped many jazz musicians. I got to sing in that festival with Harold Mabern and Jamil Sulieman Nasser and, you know, other jazz giants of the time.

AAJ: They played a lot with George Coleman, and I heard they called themselves the Memphis Mafia.

JN: [Chuckles] So anyway, I met Jay through that group of people. Now, at this point she was married to Frank J. Clayton, the drummer, and they were part of the downtown loft scene, playing Free Jazz, and they were running concerts in their loft in Brooklyn as well, and she was performing in concerts in Kirk Nurock's loft on 23rd Street, just voice and piano, or in Kirk's free vocal group, "Natural Sound." When I first heard her, I was really impressed by Jay. I liked her clarity and authenticity and, you know, musicality.

It was very exciting for me because they were doing Kirk's compositions, which are very modern. His work has tinges of jazz, musical theater...like modern art songs in a way. He's an incredible musician, and was indirectly the reason I moved to Berlin. He was leading the jazz department there, and encouraged me to apply when they were searching for a vocal professor.

AAJ: Not a lot of people know that Warne Marsh and Lennie Tristano were among the first musicians to record and perform Free Jazz. And I'm wondering, in the lessons that you did with Warne, whether you ever talked about this or practiced it at all?

Were you in New York when you first started studying with him?

JN: No, I was in California, in Pasadena. We lived in the same town. In high school, I had a boyfriend who played saxophone and studied with Warne. And of course, I loved jazz and wanted to scat, so he said, well, you can learn to improvise with your voice—I'm sure Warne could teach you. And he introduced me to Warne. I had been learning Ella Fitzgerald solos, and it was fascinating, but I wanted to scat like a horn player, in a more modern style. My favorite singer at the time was Mel Torme. What a great improviser. What a great musician, drummer, arranger, everything.

AAJ: And he did these records with Marty Paich!

JN: I know them all by heart. Yeah.

AAJ: And so great. All of that stuff.

JN: Later, during my college years, my musical partner and boyfriend was a guitarist, Don Better, who was part of the Pasadena scene, along with John Tirabasso, Patrick Smith, and all those guys, and Warne. They all taught at the same building. Anyway, I was deep into the Lennie stuff from the time when I started studying with Warne, you know. I had my first lessons with him at 18, when he gave me Charlie Parker's, "Parker's Mood" to learn. I came back six months later, you know, because I'd never learned a Bird solo before. Oh, yeah. You know, it took a long time to learn! During that time, I was also studying classical singing and wanted to be an opera singer.

I just wanted to do everything. I was just like, give it all to me. I want to do all kinds of vocal music! And I was transcribing all the vocal solos I could find. And there weren't many, it was just Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald and a few by Annie Ross. Then I heard Anita O'Day. Then there was Betty Carter.

And, I mean, I was listening to all that stuff, but I wanted to do what Warne was doing. Right. And, you know, I was so, um, optimistic to think that I could learn that! But I did my best, and he did his best to teach me.

AAJ: Were you the first singer to study with him? I mean, there's not that many singers out there that would have engaged in the music as you did back then, I would think.

JN: That's true. I was definitely the first vocalist and at the time, the only one. And then years later, when we had our gig at the Vanguard for a week in 1978, I got to sing Lennie Tristano lines, singing Lee's harmony lines with Warne on the melody. Yeah, that was really fun, my New York debut. Tardo Hammer was on piano. He still plays in New York.

AAJ: Did you and Warne practice any Free Jazz techniques?

JN: No, we didn't practice that, but yeah, we talked about it. I mean, for him, it wasn't a major part of his practice. He was practicing tunes, you know, and teaching tunes. He was like, yeah, we tried that, and it was interesting, and, yeah, there was some nice stuff. You know how laid back and dry he could be.

I did work on it with Jay and other singers, and, just for fun and variety, I did some experimental performances in Berlin. But I've really always been more interested in the lyrics and the changes—harmony, melody and rhythm. Actually, the Lennie people, as we discussed, were very rhythmic, very harmonic and very melodic in their free playing, which is unusual.

AAJ: I wrote a piece about trying to play free jazz with others when I was younger. (Jazz and the Rules of the Knife Fight) And I remember it being a terrifying experience. I mean, you take away all those props that you rely on, you know, chords, tune structure, melody. It was all about listening and texture and I was horrible at both at the time.

I have a friend who's a great guitarist, and he told me once he spends perhaps half his practice time just playing free. And he said it helped him overcome the urge to be a perfectionist which really dominated him when he was younger. Perfectionism is great on some levels, but it's really dreadful in others. Because it's such a horrible taskmaster, and it can really mess with your head and get in the way of learning. And he said, he had to kind of get clear of all that. His free practicing is focused on the idea that there is no way to be "wrong" in your playing. It helps to free yourself from being obsessed with the idea that you are somehow not playing "properly." You can do away with the idea of somehow "failing" or not playing well enough. It's not relevant. Free is, what it is, in that moment.

JN: I know what you mean. I have a roommate in New York who's a free jazz pianist. And wow, can she be a perfectionist about whether you're really being present in the moment!

Lee Konitz could also be very strict with that. Like, are you really doing something you never did before?

AAJ: There was a singer a lot like Jay who I came across in England, I don't know if you knew of her at all, named Norma Winstone. She and Jay must be almost exactly the same age as I think about it.

JN: I know Norma very well. I was able to invite her to come to the Jazz Institut Berlin and give a workshop. She and Jay were in a group called Vocal Summit with Bobby McFerrin, with Lauren Newton, and Jeanne Lee. This was the first five-voice a cappella improv group. It was originally put together by a German producer for a single concert and recorded off the bat like that.

AAJ: So, what was/is the appeal of Free Jazz for you? I mean, as you say, you've spent so much of your career mastering the American songbook. Writing lyrics for instrumental solos you vocalize.

JN: I began exploring Free Jazz when I was still in my twenties and just looking for all possible forms of vocal improvisation. I listened to people like Cathy Berberian and Yma Sumac who had this amazing five octave range. Crazy improv stuff. I just was listening to everything.

Actually, I've been a fanatic for vocal improv my whole life, and I got into Free Jazz at that point because I wanted to find an area where you could use both vocal technique and creativity, you know, and be part of it. And I joined a free jazz trio with a poet Julia Lebentritt for a while, and Glen Velez, who's an amazing frame drum percussionist.

Then I was in another group with Jeremy Steig, the flautist, and we did psychedelic rock! I wore a day-glow dress and danced and scatted on rock tunes... This was New York in the 1970s. It was like, let's do everything. Let's explore. It's funny, it's nice to remember all that.

And then Jay moved away for 20 years, to raise her kids and teach in Seattle, Washington, at Cornish. Whenever she'd visit New York, we'd get together. And after I moved to Europe in 1992, whenever I came back to the city we'd get together and go hear singers. Then we began our duo project in 2014.

AAJ: Did you manage to gig anywhere with it?

JN: Yeah, we did. We gigged at the Metropolitan Room where Annie Ross used to sing every week. And then we presented more recently it at the Soapbox Gallery. A year and a half ago or so.

AAJ: A friend of mine, who was also a Lennie student, talked a lot about the repetition of the studies he did. The depths he went to in learning a solo. For example, he said when he was learning solos (transcribing), Lennie had him learn Lester Young's solo on Lady Be Good. He said, "Lennie would make me play it an hour a day, every day for a year!"

JN: I'm not surprised. I mean, Warne and I worked on each standard for three months. I had to write a solo every week for one song and stay with it for three months. I was working on "Bird of Paradise," the Bird solo on "All the Things..." for at least four months. So yeah, that's how we did it. It's like: repetition works.

AAJ: And that's the thing. You sort of train not just your fingers, but your body and your mind, linking it all together. The pianist Aaron Parks has a similar philosophy about how you need to combine the intellectual, in terms of practicing, with the physical. You know, rhythm is a physical thing. Harmony is an intellectual thing. And melody could be thought of as a kind of heart thing, a spiritual thing in a sense. And it's an interesting approach to studying music that appeals to me, you know, and always made a certain kind of sense.

JN: Well, it's worked like that for 3,000 years of Indian music, right? It's all about hearing it and repeating it, with ragas and rhythms too.

So, the album with Jay is in a way, a bit of the history of vocal jazz improvisation. It includes songs by each of us, in duo or solo with various combinations of the other musicians. And Jay does two originals, freely improvised pieces that also include poems. This is one of her big things. She loves poetry and speaks the lyrics, then sings a line, then speaks. It's beautiful. And we sing my lyrics to Curtis Fuller's "Sagittarius," "He's A Man," and Idris Suleiman's "Orange Blossom," now called "With You," and Bob Brookmeyer tune, "Hum," called "You." I also wrote the lyrics to Kenny Dorham's "Lotus Blossom" and to Phil Markowitz's tune, "Beloved." And then there are three of my own songs. So yeah, it's not a typical CD in that we didn't just pick one topic, like a CD of ballads or a CD of standards or a CD of originals.

We wanted to explore so many areas of vocal improv. And, I think that is one of the primary things about this album: you don't often hear two singers improvising together in a masterful way. We are both of us at a similarly dedicated level of improvising, and we can really fly together. That's why we called it Voices in Flight (GAM Music, 2023). There's this feeling of being able to do anything and you don't have to worry about the other person, take care of them, make sure they're with you, you know, like with many singers. We're quite contrasting in sound and also in style, but we can adjust and it's always a beautiful experience; we give each other space and inspire each other.

AAJ: Was this the first time you've actually recorded together?

JN: Well, we recorded together with Kirk Nurock, but I don't think it ever came out. So yeah, It's a first.

AAJ: Apart from Vocal Summit, do Jay and Norma stay in touch, do you know?

JN: Jay and Norma are actually good friends. And Norma also sings standards as well. Jay doesn't write lyrics, but that's where Norma and I have a lot in common. Norma has written great lyrics to lots of Fred Hersch tunes, and many other composers too.

They're both now in their 80's, in that generation, so they were at the forefront of the new vocal jazz, breaking ground, developing new things in free improv but also doing standards, so you could relate to them and kind of then hear how far out they took it. I mean Norma's work with Azimuth, right, with Kenny Wheeler, that was just incredible.

Anyway, back to Jay. Her first album was called All Out! and on it she really does go out! She loved vamps, like on her "7/8 Thing," free pieces and duets with drums. She was always doing that kind of repertoire, but also had gigs where she just sang songs.

AAJ: It's kind of courageous, you know, to go out and do that the way she does. I mean, to kind of lay it all out there like that pretty much every time you perform. It's a real challenge. There just aren't that many singers who will do that. Come to think of it, not that many instrumentalists who will do that either. We all have our safe places while we're playing we can go to if we need to, on the bandstand. So Free Jazz is a bit like performing a high wire act without a safety net.

JN: And thank God, because most of them can't do it very well. I'll be honest, I mean, I don't really want to hear free improv from most people because they haven't done the work, and they're not really listening to what's going on around them, let alone reacting to it. I can enjoy it from Jay and her way of doing it. Because it's not just for her benefit. It's because she's expressing the meaning of the words, and being in the moment, or letting go, or some rhythmic thing, but always searching for some beauty.

It's not just about screaming and expressing yourself in order to get something off your chest... unless you're Abbey Lincoln with Max Roach.

AAJ: You have to be trained for it.

JN: You need a trained ear so that you can respond to other people. So, this was actually one thing that Warne did in our lessons that was very much along the lines of what you would do in a free improv situation.

We would improvise over a tune, just voice and sax for 20 minutes. Yeah. You have to hold your own melody line at the same time that you're hearing the other person's line and intertwine with it, react to it or get lost and find your place again. And with Warne, it was a challenge! At least that was how it was by the end of my studies with him. There was no more giving out information, you know, we were just doing it together—making music.

Yeah. It was like being an athlete. You know, you push yourself to your limit when you work with a master. You have to feel your where limits are in order to get better. Singing with Warne was like working out with a master trainer.

AAJ: Do you remember the moment you made the switch from thinking of yourself as a classical singer to just a jazz singer?

JN: I remember when I stopped studying opera. I'd studied at N.E.C and although I loved the music, I decided that I wanted to be an improviser. It was not an easy decision, but I felt I needed more freedom.

It took two years for me to stop singing with vibrato all the time! Jazz is traditionally sung using speech voice, like African music. You train to have vibrato in the classical genre, but in jazz you use speech voice and let the vibrato come in at the end. (There's a Mel Torme video, where he talks about this, Jazz Casual. It's great).

AAJ: So when you were doing the record with Jay, did you find when you were recording, both of you were consciously adapting to the material that you were doing.

JN: Of course, we always did. That was the whole point of it, that we are different as a duo than we are separately. And the whole is greater than one.

AAJ: Right. That's an interesting comment because not everybody would do that. There's a track of Lennie playing with Zoot Sims, of all people, that's fascinating because of that.

JN: I remember Warne loved him.

AAJ: Zoot plays "How Deep is the Ocean." And it sounds like it's a live date, and you can hear that everybody in the band is adapting their playing, to a degree. And Zoot is playing that hard swing like he always does, but still everyone's trying to meet his fellow musicians on common ground. Which is really interesting, given the people on the gig, you know.

JN: Because they're all such strong personalities. It's a balancing act, you know, keeping your own personality and keeping your strength without being too influenced by the other person. And I would say that in my case, I was, um, 12 years younger than Jay and she was a kind of a mentor figure, so it took time to find our balance.

Although I didn't officially study with her, I did tend to get, you know, overly influenced by other singers at times in my early days. And that's why I finally felt really comfortable having our duo when I was older, because we were equals. Friends. Yeah. It's interesting that you brought that up.

I remember that there was a really good tenor player named Ned Otter who was studying with George Coleman, and I was thinking about studying with George because I wanted to learn another approach, you know, that wasn't the Tristano way because I started to feel suffocated by that, as I've told you before.

It was partly, I think, because there were approved musicians to listen to... and no mention of John Coltrane, for God's sake. There wasn't enough emotional expression in it for me, although it was intellectually stimulating and exciting. I just was never carried away by emotion in the music. I was mentally excited. You know?

AAJ: I totally get that. I mean, I was really into Wes Montgomery at one point and it seemed so at odds, at the time, with the Tristano approach. I didn't really realize until I was much older that one was teaching me how to resolve the other.

I remember asking Warne about his influences, besides Lester Young. Just, you know, who are the players that you listen to that you really like? And the two people he immediately came up with were John Coltrane and Stan Getz. And I found that so interesting and in some abstruse way telling me something about himself, though I couldn't quite figure out what it was.

[His interest in] Getz was because of his sound particularly. But he talked a little bit about Coltrane. How he admired him. And it's stayed with me.

JN: You know, he never talked to me about learning a Coltrane solo or anything. It was always Prez and Bird and Louis Armstrong, and Lennie's list of people. And that was great and I learned a lot of those, but I learned more solos as life went on and later my students came to me saying things like, "Oh, I want to learn this solo on 'Countdown' by John Coltrane;" "I'm going to sing the Kurt Rosenwinkel solo on this or that." And I was like, go for it, man. You know, they became so advanced with transcribing. That's very interesting though what you said. Because Warne did have that rhapsodic sheets of sound kind of thing, but with different skills.

AAJ: And he did a record with Hank Jones of just ballads. Which, until I'm talking to you now, I hadn't thought about, but it kind of echoes that LP that Coltrane did, just ballads. Maybe it was inspired, yeah. I don't know.

JN: Yes, maybe so. Well, it's really hard to play slowly, you know...

AAJ: Well, yeah. And to make it swing, even for a singer. To hit that sense of skipping forward just right.

JN: It's really hard for young men; let me let me tell you that!

AAJ: I don't disagree. It's almost the exact opposite of Free Jazz in a way. And just as challenging. Thanks for taking the time to talk with us, we appreciate it.

Tags

The Jazz Life

Judy Niemack

Peter Rubie

Jay Clayton

Warne Marsh

Lennie Tristano

Gary Foster

Charles Mingus

Steve Reich

Lee Konitz

archie shepp

Ornette Coleman

cobi narita

Amina Claudine Myers

Joanne Brackeen

Harold Mabern

Jamil Nasser

George Coleman

Frank Clayton

Kirk Nurock

Marty Paich

Don Better

John Tirabasso

Patrick Smith

Annie Ross

Tardo Hammer

Norma Winston

Bobby McFerrin

Lauren Newton

Jeanne Lee

Cathy Berberian

Yma Sumac

Julia Lebentritt

Glen Velez

Jeremy Steig

Curtis Fuller

Idris Suleiman

Bob Brookmeyer

Kenny Dorham's

Phil Markowitz

Fred Hersch

Kenny Wheeler

Abbey Lincoln

Ned Otter

Kurt Rosenwinkel

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.