Home » Jazz Articles » Building a Jazz Library » Miles Davis: The Real Second Great Quintet

Miles Davis: The Real Second Great Quintet

Courtesy Jim Marshall

Tony Williams never liked the way George Coleman played, and the direction the band was moving in revolved around Tony. Tony wanted someone who was reaching for different things, like Ornette Coleman. Sometimes when I would finish my solo and start to go in the back, Tony would say ‘Take George with you.’

—Miles Davis

Davis' second great quintet is likewise agreed to be the one with tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter, pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams—which recorded another string of classics, exclusively for Columbia, beginning with Miles In Berlin, recorded in autumn 1964, and ending with three of the tracks on Filles De Kilimanjaro in 1968.

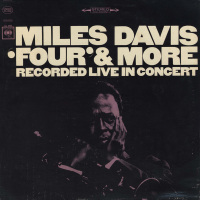

A case can be made, however, to say that the second great quintet should really be considered to be the one with Hancock, Carter and Williams and tenor saxophonist George Coleman, aka The Memphis Monster. This lineup was together for just over twelve months in 1963-64. It never completed a studio album but it is documented on three five-star live albums recorded for Columbia: In Europe: Recorded Live At The Antibes Jazz Festival, My Funny Valentine: In Concert and Four & More: Recorded Live In Concert. Under the new scheme of things, the Shorter quintet becomes the third great quintet.

Whatever your point of view about this, there is no argument that Coleman is the forgotten saxophone colossus in Davis' story, overshadowed by Coltrane (and on occasions by Sonny Rollins) in the first quintet, and later by Shorter. The fact is that the Coleman albums are landmark items, too—for Davis' playing, and for Coleman's, and for that of the new rhythm section and its seventeen going on eighteen-year-old drummer.

Almost for the last stretch in his career, Davis, whether playing open or with the Harmon mute, is exploring mostly chord-based rather than modal or abstract material. Some of the tunes are slow to medium tempo ballads, others are up-tempo belters, and in both Davis' performances at times reach unprecedented levels of intensity, often high in the trumpet's upper register. Coleman is extraordinarily well matched. His tumultuous, virtuosic sound and ability to tell linear stories in his solos combine to create an idiosyncratic style distinct from that of any other tenor player of the time. Few saxophonists aside from Rollins could in 1963-64 go head to head with Coltrane, but one feels Coleman would go the full ten rounds. (See the YouTube clip below for how Coltrane facilitated Coleman joining Davis). Hancock, Carter and Williams, while not yet as near-telepathically bonded as they would become, are irrepressibly dynamic, a breath of fresh air.

We may never know for sure why Coleman quit the quintet after only a year, to be replaced, briefly, by Sam Rivers and then by Shorter. Certainly, Williams is known several times to have urged Davis to replace Coleman with a more explicitly "new thing" player. To borrow Lester Young's description of being in the same room with white racists, Coleman may well have felt a breeze, and decided he did not need it.

In Miles: The Autobiography (Simon & Schuster, 1989), Davis' recollections support that idea. "Tony Williams never liked the way George played, and the direction the band was moving in revolved around Tony," said Davis. "George was a hell of a musician. He played almost everything perfectly... but Tony wanted someone who was reaching for different things, like Ornette Coleman... Sometimes when I would finish my solo and start to go in the back, Tony would say to me 'Take George with you.' I think Tony was the one who brought Archie Shepp to the Vanguard one night to sit in. He was so awful I just walked off the bandstand."

In an interview with Downbeat in 1980, Coleman explained his decision to leave differently. "Miles was ill during that time and a lot of times he wouldn't make the gigs and it was frustrating," said Coleman. "His hip was bothering him. So there was a lot of pressure on me. And sometimes the money would be late and I'd get a cheque and have to try and get it cashed, so I really got tired of it, so I just decided to leave." Yes, well, maybe. But it feels like that is not the whole story.

Anyway, Coleman's departure was Davis' loss. But then, Shorter's arrival was Davis' gain. Things rarely go in a straight line. Before reaching for the Shorter discs once more, it is worth reacquainting yourself with these treasures...

MILES DAVIS: THE REAL SECOND GREAT QUINTET

The three albums discussed below are included on Columbia's box set Seven Steps: The Complete Columbia Recordings of Miles Davis 1963—1964, released in 2004. The collection also includes three tracks the group recorded in the studio for Columbia, which appeared on Seven Steps To Heaven (1963). Not included are tracks recorded live in Davis' hometown in 1963, which appear on the bootleg Miles Davis Quintet: In St Louis (VGM, 1981). Miles Davis

Miles DavisIn Europe: Recorded Live At The Antibes Jazz Festival

Columbia, 1964

Immaculately produced by Teo Macero, In Europe, which has also been issued as Miles In Antibes, was recorded over three nights in July 1963. Davis' statement that "the direction the band was moving in revolved around Tony" might seem unlikely given the size of Davis' ego. But the evidence is here in the grooves, right from track one, an energised reading of Johnny Mercer's "Autumn Leaves." The realignment of the conventional relationship between the front line and the rhythm section which occurred during Shorter's 1964-68 tenure with the quintet is present in foetal form, as it is elsewhere on the album, with Williams steering the direction of Davis and Hancock's solos almost as often as they steer it themselves.

Revealingly, there is less interaction between Coleman and Williams and at times they actually pull in different directions. Further, on Cole Porter's "All Of You," it is Coleman who establishes the trajectory of the piano solo which follows: his close to honking and screaming final chorus is maintained in Hancock's blues and gospel-infused styling. Williams takes just one solo, a jaw-dropper, on the closer, Richard Carpenter's "Walkin,'" during which audience members can be heard applauding after every few bars. The other tracks on the original LP are Victor Feldman's "Joshua" and Davis' "Milestones." Throughout, the vibe frequently turns on a dime from raw and pugnacious to elegant and vulnerable and back again.

Miles Davis

Miles DavisMy Funny Valentine: In Concert

Columbia, 1965

Probably the best known of the three albums with Coleman, My Funny Valentine was recorded at the Philharmonic Hall, Lincoln Center on February 12, 1964. So was the third album here, Four And More (see below). Davis or producer Teo Macero took the decision to put the slow to medium tempo numbers from the concert on My Funny Valentine and the fast ones on Four And More. And it almost certainly was Davis or Macero, not Davis and Macero, because, as Macero told it in Ian Carr's Miles Davis: A Critical Biography (Quartet, 1982), Davis was not on speaking terms with Macero at the time; he was still furious was about the release of the orchestral project Quiet Nights (Columbia, 1963), which he considered unfinished. Davis did his thing onstage for the live albums with Coleman, while Macero did his elsewhere in the house with the sound engineers.

Davis also had a moment with his band minutes before the performance began. Ron Carter relates in his liner notes for the 2005 Columbia Legacy reissue of My Funny Valentine that, while the musicians were assembling in the wings, Davis told them the event was a benefit for a NAACP-sponsored campaign for voter registration in Mississippi and that they were not going to be paid. "I began to pack up my bass," wrote Carter. "Miles asked where I was going. My response was 'Home!...' I said I thought it was unfair that after being off for two or three weeks, he expected us to play for free at the first job back." Davis had little choice but to agree to pay the musicians ("No one asked how much," wrote Carter)—and the quintet, now more than usually wired up, went onstage a few minutes later to deliver a talismanic two-hour performance. My Funny Valentine is one of the half-dozen most beautiful albums Davis ever recorded.

Miles Davis

Miles DavisFour & More: Recorded Live In Concert

Columbia, 1966

Fasten your seat belt, please, before hitting Play. The six selections from the Lincoln Centre concert on Four And More include five which are taken at the speed of light: "Walkin,'" "Joshua," Davis' "So What" and "Four" and Feldman and Davis' "Seven Steps To Heaven." It is safe to assume that at least two of these opened the gig: not only was this Davis' standard practice at the time, but also it is hard to imagine that the quintet could go onstage minutes after the fractious moment Carter wrote about and deliver a sumptuous, leisurely paced ballad. The collective testosterone level would need to be discharged a little first.

The one tune that is taken at a moderate tempo is Isham Jones' "There Is No Greater Love," a piece that Davis performed relatively infrequently. But it is played at a considerably faster lick than it was on The New Miles Davis Quintet's exquisite reading in 1955. Then, it was taken at what Quincy Jones memorably called "junkie tempo." Coltrane, Garland and Jones were all definitely strung out at the time and Chambers might have been, too. But no-one in the 1964 quintet was on heroin (though Davis was getting deeper into cocaine). In any event, Davis and Coleman's solos are 360 degrees different than Davis and Coltrane's a decade earlier: bluesier and dirtier. The tune is the penultimate track on Four And More, which concludes with a brief, lickety-split rendition of Davis' "Go-Go." And so ends three and a bit hours of celestial music. Are you ready for a little historical revisionism?

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.