Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Ornette Coleman: The Territory And The Adventure

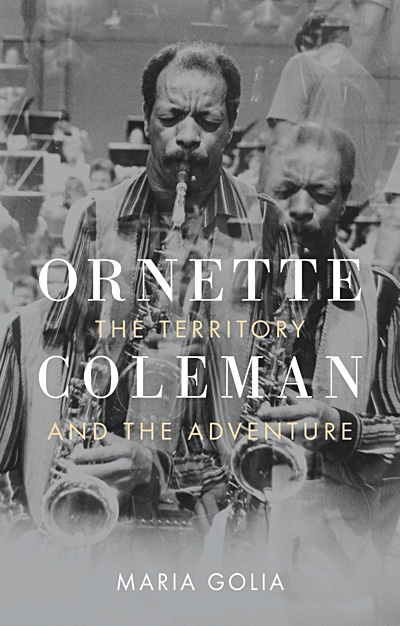

Ornette Coleman: The Territory And The Adventure

Coleman had a vision that drew a circle of accomplished musicians and attracted the admiration of accomplished non-musical artists. But a brilliant vision wasn’t enough. He needed the will to persist in the face of scathing criticism from jazz musicians and listeners.

Ornette Coleman: The Territory And The Adventure

Ornette Coleman: The Territory And The Adventure Maria Golia

368 Pages

ISBN: #9781789142235

University of Chicago Press

2020

Ornette Coleman holds a singular place in jazz history. The seeds of change in jazz had been sewn by Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, John Coltrane and their cohorts, but Coleman's appearance at the Five Spot Café in 1959 kicked the process into high gear. Author Maria Golia's mise en scene of Coleman's life and her insights into his persona provide ample material to understand his initial disruptiveness and his long-term influence.

The book can be seen through three lenses. One is the chronological narrative of Coleman's life and career, the second concerns what Coleman had to say about the work and the third is what the author has to say about the work and about Coleman. These last two are intertwined, because Coleman could be cryptic and contradictory in his verbal communications and Golia often undertakes the task of acting as his translator.

The chronology seems thorough-plenty of facts, with interesting bits of color to keep things moving. I found Coleman's life pre-New York City to be the most fascinating part of the chronology, doubtless because I knew least about this. The depiction of his life growing up in 1930's-early 40's Ft. Worth was well constructed, with enough data to flesh out the picture but not enough to weigh down the narrative. I was surprised to read that Ft. Worth was sufficiently prosperous to draw a wide range of musicians, giving Coleman the chance to hear many kinds of music. There were large venues for well-known jazz musicians like Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong and dance houses or institutions where one could find everything from polkas and blues to R&B. Then, there was the church, an important influence on Coleman.

Golia tells interesting stories about musicians from Ft. Worth or other parts of Texas, including T-Bone Walker, who acted as the "eyes" for bluesman Blind Lemon Jefferson and Eddie Durham (later with Count Basie) who, taught by his father, shot rattlesnakes and sold the rattles to violinists who put them in their resonators.

Coleman was proficient enough as an R&B player to join the union and start gigging when he was 16. He dropped out of high school and the author notes Coleman's lifelong ambivalent, sometimes defensive attitude toward education. As a teen, he formed a group called the "Jam Jivers" with future collaborators Charles Moffett and John Carter, tries to participate in jam sessions (often unsuccessfully) and does a stint with Silas Green's vaudeville tent show.

Golia covers Coleman's forays to Los Angeles, where he met Don Cherry, Billy Higgins, James Clay and Bobby Bradford and New Orleans, where he met drummer Ed Blackwell. These were musicians who saw something in Coleman that others didn't and he continued to work with them for decades.

The author goes into depth on the impact and divisiveness of his initial appearance at the Five Spot Café in 1959. Coleman's music fit perfectly in the context of that highly experimental period in art and his circle included writers LeRoi Jones and A.B. Spellman, painter Larry Rivers, Cecil Taylor and Albert Ayler and filmmaker Allan Kaprow. I was surprised at how much he played informally with Sonny Rollins, and the degree to which John Coltrane considered Coleman a teacher.

His travels to Europe are covered and the increasing importance Coleman put on writing large scale works, which Golia says was driven, to some degree, by Coleman's defensiveness in being thought of as a "cornpone' musician. There is coverage of his trip to Morocco to jam with the musicians of Joujouka and new information to me about his loft, called (and record label) "Artists House." It's interesting to note that after Coleman made his initial splash, he continued to face resistance and was far from financially flush.

As time passed and his value and stature in the jazz world was established, the sense of inevitability in the story increases and the narrative momentum decreases. The author dedicates a lot of attention to the Caravan of Dreams Performing Arts Center in Ft. Worth, at which she worked from 1985-1992 and in which she clearly is very invested. Coleman was involved in the founding of the Center and was the first act to play there, so it makes sense to spend time on its inception and those instances when he goes back to perform. However, much of Golia's talk about Ft. Worth and the demise of the Center is off topic.

Let's look through the second lens of the book-what Ornette Coleman has to say about his music. Coleman understood that emotion, not musical values, per se, was at the core of his music. Something that he said about music in church was telling: "[church music was] created for an emotional experience...I didn't have to worry about chords, keys, melody if I had that emotion that brought tears and laughter to people's hearts." Throughout his life, he pushed back against his musicians' reliance on preconceived patterns. He says: "My playing is spontaneous, not a style. A style happens when your phrasing hardens."

He tries to develop a more theoretical explanation of what he does as his career goes on. He described his melodies as "territories"-a sound landscape in which many things were possible. He was frustrated that musicians couldn't be seen the same way as scientists: "Only the scientists, technicians and doctors can actually use the whole world as a guinea pig. But artists, we can't do that. [If you make new music] someone would say 'this is way before its time.' They don't say that about television. They don't say that about penicillin." Finally: "In my musical concept [which he called "Harmolodics"], not only the sensation of tone to the nerves is released, but the very reason for the use of the tone..."

One can see why Golia's translations of certain musical specifics, like Harmolodics, can be helpful: "the harmony melody and movement (the rhythmic aspects) of a composition are assigned equal value as the basis for improvisation." As a point of general description, she says: "Coleman wanted to "rescue improvisation from ephemerality by presenting it as a model for all genuine communication." Or, "Rather than diminishing the music's requisite virtuosity, he proposed an alternative means for its expression, namely as an intimacy with one's instrument and fellow instrumentalists, as extensions of one self." And: "Ornette was looking for those notes, the ones that feel no pain."

Golia's biography gives us a good sense of Coleman's complex personality. He is described as quiet and at other times, talkative; non-confrontational and bluntly expressive about being underpaid; sometimes "Buddha-like" and sometimes withdrawn in the face of negative criticism. He had a vision that was compelling enough to draw a circle of accomplished musicians and to attract the admiration of accomplished non-musical artists. But, a vision wasn't enough. He needed sufficient will to persist in the face of scathing criticism from jazz musicians and listeners. If you don't know his music, listen. There are two basic varieties: acoustic and electric. In an associated story to be published soon, I go into more detail about his music.

Tags

Book Review

Steve Provizer

University of Chicago Press

Ornette Coleman

Cecil Taylor

Sun Ra

John Coltrane

Five Spot Café

duke ellington

Louis Armstrong

T. Bone Walker

Blind Lemon Jefferson

Eddie Durham

Count Basie

Charles Moffett

John Carter

Don Cherry

Billy Higgins

James Clay

Bobby Bradford

Ed Blackwell

Albert Ayler

Sonny Rollins

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.