Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Don Byas: Sax Expat

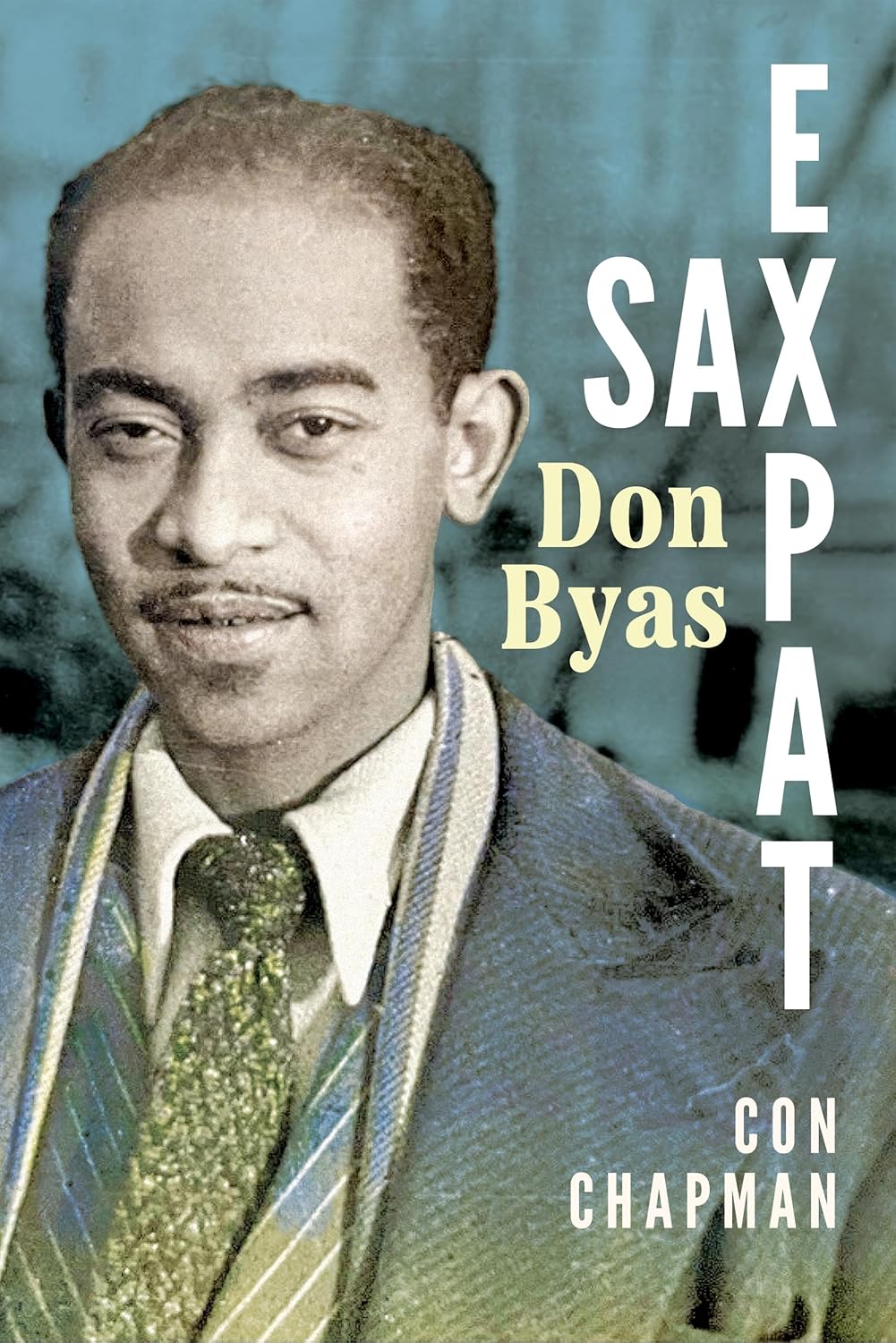

Don Byas: Sax Expat

Don Byas: Sax Expat

Don Byas: Sax Expat Con Chapman

233 Pages

ISBN: 9781496856081

University Press of Mississippi

2025

Don Byas, a tenor saxophonist, who was regarded with great respect in his day, is, unfortunately, now not much more than a name. In part, it is because he has been gone for half a century. Yet that hardly is a sufficient explanation for neglect. Others of his cohort, like Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young or Ben Webster, are hardly forgotten. They have many followers. Among players, their influence, even if only referentially, survives. But Byas also chose to remove himself from the American scene for the latter half of his career, becoming an expat in Western Europe. For Byas, a Black man, this was not a statement about the intolerable racism that characterized the United States and drove other compatriots to Europe." Discrimination had nothing to do with it," Byas asserted. (p. 105) For Byas, paradoxically, it was a gesture undertaken in search of recognition, which he thought he had never properly received in the United States. This was true, but only to a point. Other musicians knew.

Buddy Tate observed in 1943 "Nobody in the world could touch Don Byas at the time. Nobody. Not nobody I know. He had everything—speed, sound,,,He was ahead of everybody." (p. 53) After watching Byas at Monroe's Uptown House, Charlie Parker observed "Don Byas was there playing everything there was to be played."(p.76) A young Gerry Mulligan had no interest in going up again Byas: "Don Byas would have cut me five new belly buttons."(p.77). And, here, perhaps was the root of the problem, Don Byas knew too.

When his competitive instincts were aroused—and alcohol seemed to intensify them—he could be difficult to the point of being dangerous. He supposedly pulled a gun on Duke Ellington, a knife on Charlie Parker, and got himself fired from Count Basie's band although he asserted his time with Basie's band " [was} the happiest... of my life."(p. 54) Byas knew, and modern things like citation indexes back him up, that in the mid-1940s, only Coleman Hawkins had more of reputation. He was the equal of Lester Young and Ben Webster, but that did not last. By the 1950s, his star had dimmed. By the 1970s, when he passed from the scene, Byas was remembered, but that was about all. It was a melancholy ending to what, based on sheer talent alone, should have been an astonishing career. Byas was forever in Hawkins' shadow. It obsessed him. "I know what he's doing," Byas complained of Hawkins. "Why can't everyone hear what I'm doing?" (p. 30) Comparisons with other white players, perhaps excepting Bud Freeman, are irrelevant. He was out of their league.

Byas was from eastern Oklahoma, born in 1913, and from a multiracial background that included Native American, Black and Mexican. The surname itself (Byas, like Baéz) is indictive of a crypto-Jewish (Mexican) background stretching well back into the seventeenth century in the Southwest, although the family did not regard it as a selling point in Muskogee. His family was, especially by the standards of the Great Depression, middle class. Byas himself attended Langston University, a historically Black University. Whatever else Byas was, or claimed to be, he was certainly not only musical, but bright. When he moved to Europe, he learned to speak French and Dutch fluently, neither of which is easy, and was thoughtful, articulate and bec fin, if a problem drinker.

Byas came up through a mix of bands including Eddie Barefield, Buck Clayton (on whom he played a mortifying practical joke), Eddie Mallory, Don Redman, Lucky Millinder and Andy Kirk: first on alto, then tenor. He was for a time in California, where he made no impression. Finally, in 1941 (he was never drafted into World War II), Byas broke through with his solo on "Harvard Blues," with Count Basie, a performance characterized as "one of his best recorded solos." (p. 50) He ended up in New York City, very much a presence on the emerging bop scene on 52d Street in the 1940s, although never quite displacing Coleman Hawkins in either shadow or substance. Arguably, he would soon be eclipsed by Charlie Parker, with whom he had a, well, volatile relationship. He listened intently to Benny Carter and especially to Art Tatum, whose harmonic sensibilities were overwhelmingly important to Byas. "You [Byas] play the saxophone like I play the piano," Tatum observed. (p. 33).

Byas went to Europe after World War II, and spent time in France, Spain, and finally, Holland, where he permanently settled. He had had earlier unsuccessful relationships and a marriage, but he finally married for good and had a family with Johanna Eksteen, a Dutch woman, with whom he appears to have been reasonably content. He never, it is true, made a great commercial success of himself, but neither he nor his wife appeared unduly troubled by that, even if life could be tight. It was seemingly a choice, something along the lines of the now dated saying that "Americans live to work, but Europeans work to live." Byas clearly believed that, and whatever it cost, it cost. Whether he was ever truly at peace with himself and his stature in the world of jazz is another matter. And his troubled relationship with Ben Webster and his occasionally extravagant public behavior surely suggest otherwise. It is not easy being great, but unappreciated. This, to sum it up, was Byas' problem. Billy Taylor said "I don't think Don was ever in the right place at the right time." (p.91)

It is a complicated issue: not only a personal one, but a stylistic and therefore, a musical one. For one thing, as many students of jazz have observed, it is a small world, and something of a zero-sum game: your success detracts from mine, and there can be only one "best" player at a time. It may be nonsense, but a lot of professions do in fact work that way in the public mind. Chapman says this (p.152), and jazz writer Michael Steinman has made the point repeatedly. "We already got one of those. What's the use of another?" It is, to put it mildly, a simplistic view of looking at the world, but professional athletics and politics are not really all that different. Then there is the whole "swing to bop" discussion. Harmonically, Byas may have been right in there with the most sophisticated bop musicians. But rhythmically, as both Steinman and Martin Williams note, (p.178), Byas did play a lot of eighth notes and phrased in swing eighth notes at that. Listening to up-tempo Byas can be like getting hit by a hammer, rather than the smooth flow of Lester Young or Stan Getz. It is de gustibus, for certain, but subtle distinctions require a certain agility of thought that is uncommon. And then, there is personality, ego and temperament. Some musicians, like Benny Goodman have to be the center of attention. Others, like Byas, might well have liked that too, but, maybe, in the final analysis, that was simply too much trouble for him.

An interesting portrait of a too little known master.

Tags

Book Review

Don Byas

Richard J Salvucci

University Press of Mississippi}

2025 {{m: Don Byas Coleman Hawkins Lester Young ben webster Buddy Tate Charlie Parker Gerry Mulligan duke ellington Count Basie Benny Carter Art Tatum Billy Taylor Stan Getz Benny Goodman

2025 {{m: Don Byas Coleman Hawkins Lester Young ben webster Buddy Tate Charlie Parker Gerry Mulligan duke ellington Count Basie Benny Carter Art Tatum Billy Taylor Stan Getz Benny Goodman

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.