Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » George Brooks: Global Conversations

George Brooks: Global Conversations

Summit reflects everything positive about "Indian fusion." The Berkeley, California-based Brooks is deeply steeped in Indian classical music traditions and theory, and is routinely sought after as an accompanist by legendary Indian musicians including Hussain, flautist Hariprasad Chaurasia, percussionist Trilok Gurtu, and mandolonist U. Srinivas—just to name a few. In many ways, Summit is a mutual respect society in which all performers—leader and sidemen alike—offer pivotal influences and ideas that are synthesized into a listening experience that's organic, invigorating and accessible.

Raga Bop Trio, another recent Brooks project, takes a driving, more groove-based approach to Indian fusion. Also featuring Smith, along with Indian electric guitar innovator Prasanna, the group's 2010 self-titled Abstract Logix debut explores funk, rock and even occasional Caribbean influences. Brooks also has a trio with celebrated keyboardist Terry Riley and tablaist Talvin Singh. The band performs compositions by Riley and Brooks, as well as Indian classical pieces. To date, it has toured Europe and is considering recording options and future performances.

Brooks' eponymously-titled Elements (Earth Brother, 2011) is named after his group featuring Kala Ramnath and Dutch harpist Gwyneth Wentink. Elements focuses on original works by Brooks and Ramnath, as well as ragas infused with European classical and jazz perspectives. Ramnath is considered one of world's foremost Hindustani violinists, as well as someone open to taking chances and integrating her sound into myriad world music and jazz contexts. Wentink is an award-winning musician, renowned in classical circles, but seeking to stretch her boundaries by exploring the vast potential available within Indian music. With complementary goals and shared passions, Brooks is brimming with enthusiasm about the possibilities open to Elements in the future.

AAJ: Describe how the Elements group came together.

GB: About five years ago, I was asked to perform with Hariprasad Chaurasia [Hariji], who I first started playing with in 2000. For me, he's the most amazing wind player to ever grace the planet. I learn so much every time I listen to him. And he's not someone I ever expected to play with. It's an incredible treat. The concert was a fundraiser for an Indian organization at the Waldorf Astoria in New York. Hariji and I played this concert with Vijay Ghate on tabla. It was recorded and made into an album called Kirwani: Message of the Birds (ArkivMusic, 2006).

A very young harpist named Gwyneth Wentink from the Netherlands also performed with us. This young woman, who's a famous harp virtuoso in the classical world, had just started studying Indian music. I was impressed with Gwyneth's musicality and eagerness to expand her musical horizons. Subsequently, we did a few gigs together with Hariprasad. When the Kirwani: Message of the Birds album came out, there was a release concert at the Barbican in London, and then we played the Lille Opera House, which was the Euro city of 2009. That same year, Gwyneth had won the Dutch Music Prize, which provided her with financial support for several years. In the final year of the prize they have a big "coming out" concert and she invited me and Hariji to play without drums. It was an acoustic thing at a beautiful concert hall called the Muziekgebouw in Amsterdam.

So, Gwyneth and I had established a musical relationship through these gigs with Hariji. Because she's a classical player, I would write arrangements of Hariji's compositions, as well as accompaniment ideas. I was getting into the idea of using the harp more and more. In winter of 2010, I performed four concerts in India with Gwyneth and Hariji. Hariji has a school in Bombay and Kala Ramnath lives very close to it. Kala and I have worked together on several projects, including a group called Global Conversation. I always wanted Gwyneth and Kala to meet. Once, when Gwyneth and I were rehearsing, we called Kala and asked her to come to the school. She brought her violin and it immediately sounded really good with the harp.

I spent February and March writing music with Kala and Gwyneth in mind, figuring out harp parts on the piano, and working with some ideas Kala had. We all decided to move forward with a recording session. They arrived here in Berkeley on May 3rd, we rehearsed May 4th, and recorded May 5th through 6th. It happened really fast. I thought we'd do the session and maybe get one tune out of it, but it came out well enough that I wanted to make a CD out of it. After being on tour with the Raga Bop Trio for a month, with super-heavy drums and intense music, it was very satisfying to work with a harpist, deal with a lot of interesting patterns and take a more romantic approach to things.

AAJ: You've worked within many male-dominated projects. What was it like to have a project focused on female energy?

Summit, from left: Zakir Hussain, Fareed Haque, George Brooks Steve Smith, and Kai Eckhardt

GB: It's been really great. There was no clash of egos. Both Gwyneth and Kala are very accommodating. I tend to be a pretty relaxed presence. I'm not a domineering type of guy. I spend a lot of time in the kitchen at home and have raised three kids. I'm comfortable being around women and I like the way women express themselves musically. These two particular women do that incredibly well. Kala is beautiful vocalist and a technically monstrous violinist. She plays with incredible emotional impact. Gwyneth is approaching improvisation from a classical perspective and is just beginning her exploration of the Indian side of things. She spent two months in India last summer, living and studying in Delhi, so she's really committed to the concept. She's a celebrated orchestral player and is now expanding beyond that. It's exciting to be part of a younger musician's expansion and exploration. I'm looking forward to seeing where we can take the group next.

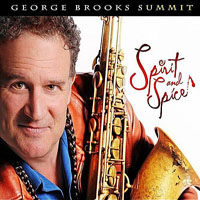

AAJ: Spirit and Spice is the first Summit record in eight years. What progression do you see from the debut album?

GB: I wanted this album to go deeper into Indian music, yet deeper into jazz too. There's a track on it called "Silent Prayer—Madhuvanti" which feels like a really effective Indian jazz piece, although people who aren't necessarily familiar with Indian music might not know it's Indian. However, anyone that knows Indian music will right away go "Oh, that's 'Raag Madhuvanti.'" There are no Indian instruments on that piece, yet it's a pretty clear expression of that raga concept. It offers a slower look at the pitches and a little more sonic ambience. The album also has some different people on it and all of the musicians have played together more often since the first album. Things were more relaxed in the studio.

The first time we got the whole band together, nobody knew what to expect, which also gave it a kind of excitement. For this one, the music had already evolved in a live context. With the previous Summit CD, nothing had been played prior to us going into the studio. For instance, "Lalita" was something I played a lot with Bombay Jazz, a group I have with Larry Coryell and Ronu Majumdar, as well as in other configurations. I heard it expressed by a bunch of different musicians and knew for the album that I wanted Ronu to play flute on it. Sridhar Parthasarathy, the mrdingam player on "Monsoon Blues," is somebody I played with previously too. I've hung out with these people in India as well, so there was a strong connection to the people and places of India throughout the making of the album.

AAJ: At the core of Summit, you have four extremely strong personalities who are leaders in their own right. How do you go about directing them?

GB: A review of the first album said, "I'm holding onto a wild horse loosely" when describing the band [laughs]. I'm just kind of directing things, but it has some of its own energy. When you're working with really gifted people like that, who are tremendous virtuosos, you have to give them music that challenges them. You don't want them to be bored playing the music. You want to excite them. Sometimes you can't get things to sound the way you want because someone is chomping at the bit to express their own ideas. But I've also seen that change with maturity. The musicians in Summit are less controlled by their desires to express themselves. Now they're looking at the music and thinking "How do we make this work as a whole?"

Working with Fareed Haque, Kai Eckhardt and Steve Smith over so much time means they understand what I'm looking for and my temperament. They also like that I give them a lot of space to create their parts and contribute to the music. I'm not someone who creates a tune in MIDI and then goes "This is what the music has to sound like. Imitate these parts." Instead, I say "I've got this concept. Here's this raga. The tempo should probably feel like this. It's in a 15-beat cycle and I have these patterns that seem to work together. Let's work with them and see how they evolve." But sometimes, I have to be strong enough to say something like "That's not what I want to hear when I'm soloing" or "That's not what want to hear behind the melody. This is a part you need to play because it makes this happen, which expresses what I was looking for the piece to say."

AAJ: Reflect on the beginnings of Summit.

GB: It began back in 1996. I'm a late bloomer. I used to hang out with Anthony Braxton and play with people like Etta James, as well as doing different kinds of commercial work as I tried to find my voice. I was working a lot with Terry Riley, who is a huge influence, and teaching a bit at Mills College. Anthony was teaching at Mills and we used to hang out in his office. In his trajectory, he skipped certain elemental things from jazz terminology and we'd exchange information. I would clarify some terminology related to chords, scales and conventions—not that he didn't know them in his own way. It was just simple stuff he perhaps ignored during his development, such as "When they say D9, does that mean a dominant seventh or a major seventh?" He would work with me as a composer and help develop me as an artist. He helped me get through some of the shit that was holding me back and taught me not to judge myself so harshly. His philosophy was "Write it and move on. Now, go out and fight for the music." He was very helpful and important to me.

GB: It began back in 1996. I'm a late bloomer. I used to hang out with Anthony Braxton and play with people like Etta James, as well as doing different kinds of commercial work as I tried to find my voice. I was working a lot with Terry Riley, who is a huge influence, and teaching a bit at Mills College. Anthony was teaching at Mills and we used to hang out in his office. In his trajectory, he skipped certain elemental things from jazz terminology and we'd exchange information. I would clarify some terminology related to chords, scales and conventions—not that he didn't know them in his own way. It was just simple stuff he perhaps ignored during his development, such as "When they say D9, does that mean a dominant seventh or a major seventh?" He would work with me as a composer and help develop me as an artist. He helped me get through some of the shit that was holding me back and taught me not to judge myself so harshly. His philosophy was "Write it and move on. Now, go out and fight for the music." He was very helpful and important to me.Anthony really pushed me, and as a result, I pushed myself and wrote the music for Lasting Impression (Moment), my 1996 debut album, which I did with Krishna Bhatt, my main musical partner at the time. Krishna and I had dinner once—he lived just a block away from me back then. Zakir and Krishna were very good friends. One day, Zakir came over and offered to play on my album. I was stunned. I had met Zakir before and had been to his father's house in Bombay, back in the early '80s, with my guruji Pandit Pran Nath, the renowned Hindustani classical singer. So, I called Zakir the next day and said, "Were you serious about that?" [laughs] He was and he came and played, and then put the record out on his label Moment Records. That's what started my association with him.

At one point, Zakir was putting together a "Zakir and Friends" gig and that's where I first played with Kai Eckhardt. After that, I put out my second Moment Records album, Night Spinner, in 1998. Somewhere in there, Steve Smith called me. He said, "I've been on tour with a tabla player named Sandeep Burman in a group with Randy Brecker. I've been thinking about Indian music a lot and been listening to your stuff. The next time you do something, if you have something for me to play, I'd be interested." I said, "Well, actually I've been writing music for the Summit CD. Maybe that would be kind of cool for you to play on." Kai then said, "I work with an amazing guitarist called Fareed Haque." That's how the group came together.

Steve was studying South Indian rhythms and really interested in spending some time with Zakir. There was a funny moment when we had all rehearsed, except for Zakir. I wrote a piece called "Frame Master" that begins with a peshkar—as in the way a classical tabla solo opens a piece. It's very rhythmically elusive and hard to keep track of where the "one" is. Steve says "Whoa! Show me that Zakir." So he gets the first opening phrase and says "Oh cool. Now, that repeats?" Zakir says "No, no. Nothing ever repeats." [laughs] I'm like, "Guys, I'm paying the engineer here. You'll have to deal with that elsewhere." Subsequently, on tour, Zakir was an incredible teacher to us all in many facets.

AAJ: Can you define Summit's mission?

AAJ: Can you define Summit's mission?GB: There are a couple of things I am trying to accomplish. One is to establish a place where I can feel really comfortable expressing a lot of different parts of my musicality. I'd like to explore the romantic, really tone-centric things that attract me to raga, but also express the musical euphoria of playing with an incredible rhythm section. I want it to all be very comfortable so I don't have to worry about things and can express myself freely. Finding a place that unifies everything is where I believe this path of Indian influences is leading. There's a whole Norwegian jazz thing happening, and French too. African music is extremely present throughout Western pop, jazz and dance forms. Indian music hasn't been able to enter as easily into Western improvised forms of music. For whatever reason, when I was young and forming myself as a musician, Indian music was a huge influence. So, I feel drawn to continually work on that and get it out there.

AAJ: When you're onstage with Summit, do you ever look behind you and go "Holy crap! The drummer from Journey and Zakir Hussain are onstage playing my music?"

GB: Yes and no [laughs]. In the '80s, I was focused on jazz and Indian classical music. Journey was not part of my musical life. I don't think I would have known a Journey tune if it hit me in the face until much later when my kids played me one. There's a song called "Lights" that's the theme song of the Oakland A's, which my kids love. A lot of people were more freaked out about me playing with Steve than I was. Playing with Hariprasad was more like "What the hell am I doing up here with him?" [laughs] Earlier on, when I was working with Zakir and Aashish Khan, I had similar feelings. It blew my mind that these guys were playing music I had written. When I play with Summit, it blows my mind too, not because of what the musicians have done in the past, but the way they play today. I'm up there going "Wow, this feels so good." I still remember after the first Summit CD came out, we played in Singapore and Hong Kong. It was the first time I didn't have to think about anything. It felt like I was driving in an incredibly powerful machine and just knew it was working. It's an extraordinary feeling.

AAJ: Expand on how your connection with Zakir Hussain evolved so deeply.

GB: I've never asked Zakir what attracted him to my music, but there was something that did. After he offered to play on first album in 1995, I also said to him, "Can I afford you?" [laughs] He said, "Let's not worry about that. Let's talk about the music, because that's what's important." We had previously done some things with Terry Riley. In fact, the first time we played together was with Terry. After we put out Lasting Impression, Zakir was performing with The Rhythm Experience, which was a locally focused San Francisco Bay Area percussion group. It was the precursor to his Masters of Percussion group, which is mainly comprised of Indian musicians. I would often be a guest artist with the Rhythm Experience.

There were a bunch of other projects at that time. Zakir was commissioned by Mark Morris to write something for his dance company and Yo-Yo Ma. He asked me to do all the arranging and then I composed quite a bit of the music as well. At that time I was doing a lot of work for Zakir, notating his compositions and writing arrangements. We also worked on music for a Merchant/Ivory film called The Mystic Masseur together, which was wild. They said, "George, put together an orchestra for us." Zakir and Richard Robbins were the composers. So, I put one together and did a bit of writing, as well as played piano. Aashish Khan and Liam Teague, a steel drummer, were there as well. I still remember playing a big party at the Telluride Film Festival for that movie. Zakir, Aashish, Liam and I showed up backstage and we ran into Salman Rushdie, who was still under fatwa. He was there with his girlfriend Padma Lakshmi, who is now the star of Top Chef. It really blew my mind.

Next, we recorded Night Spinner which was a big production for Zakir's label. Aashish Khan and Sultan Khan both play on it. I started going to India to perform and because I was sort of anointed by Zakir, I was vetted, and got to do some wonderful performances. This was in 2001, which was the first time I stepped foot into India after my initial trips there in the '80s. I was performing with Zakir and the keyboardist Louiz Banks, doing fusion shows. I kept showing up in India with Zakir and it was a cool thing. By the graces of Zakir, I got to play at midnight Sufi concerts under the full moon with Sultan Khan in front of the Gateway of India and other extraordinary things.

Next, we recorded Night Spinner which was a big production for Zakir's label. Aashish Khan and Sultan Khan both play on it. I started going to India to perform and because I was sort of anointed by Zakir, I was vetted, and got to do some wonderful performances. This was in 2001, which was the first time I stepped foot into India after my initial trips there in the '80s. I was performing with Zakir and the keyboardist Louiz Banks, doing fusion shows. I kept showing up in India with Zakir and it was a cool thing. By the graces of Zakir, I got to play at midnight Sufi concerts under the full moon with Sultan Khan in front of the Gateway of India and other extraordinary things.After going to India with Zakir, I realized what a super-potent being he is over there. In the West, he's respected as an extraordinary musician, but in India he's like Michael Jackson. He's really revered. The more I got to see him in India, the more I could understand why. He's somebody who has taken tabla way out of its traditional role, yet maintained an unbreakable bond with the tradition. He's caught flack for a lot of his projects and some people don't understand why he plays with Western musicians, but he's a restless seeker and an unbelievable well of tradition. He's the avatar of his instrument.

AAJ: How have you evolved as a musician since Lasting Impression?

Terry Riley and George Brooks

Terry Riley and George BrooksGB: I hope I have evolved a lot, although sometimes I'm surprised at how much better the first album is than what I thought of it at the time. I've learned a lot about rhythm and how to be comfortable playing with ferociously-talented drummers, which can be intimidating when you play a melodic instrument. I'm still trying to understand the balance between melody and rhythm, and I keep learning more. This can be a good and a bad thing, because sometimes, when you're ignorant and following your instincts, you can do some unique and interesting things.

AAJ: How do you look back at the Raga Bop Trio experience?

GB: It began in an interesting way. Steve and I were rehearsing for the recording of Spirit and Spice. I drove up to Oregon where he lives and we worked on a bunch of duo stuff for it. We thought "Wow, this is really cool and exciting." We thought about it as a playing scenario. Then we decided there should be a third person. Steve had done a bunch of duo stuff with Prasanna, so that was the impetus. We got together for a rehearsal and writing session. I brought stuff in and so did Prasanna. Steve also had some ideas worked up and we went from there. It was a collaborative effort, which can sometimes be challenging musically. Sometimes it's good to have a leader and subordinates. Steve wanted the drum concept a certain way and for the musicians to play a particular way. He's very exacting, which was a good kick in the butt for me.

I think I play very strong on the album and in a different way. I was playing alto, which was my first horn. It was interesting to go back to that. I thought the sound would work well with the band. It's a more penetrating sound, which works in this context because Steve and Prasanna are loud. When Steve is with Summit, he plays on a small kit with bundled rods. They're called The Steve Smith Tala Wands, which he developed with Vic Firth to play with Summit and Indian drummers, since they're relatively quiet. On Raga Bop Trio, he played with sticks and a big kit. It was a really big sound. Prasanna is a very unique musician to work with. In a single solo, he'll go from South India to '50s jazz to Jimi Hendrix to ultra-modern guitar. He's rigorously trained in Indian classical music and is also interested in Western classical music. He has musical gifts piled onto him, including perfect pitch.

AAJ: One of your most unique bands is the multi-generation trio with Terry Riley and Talvin Singh. There has to be an interesting story behind its formation.

GB: Terry and I were going to do a gig in London for the Asian Music Circuit, a prominent Asian music touring organization. They contacted me and said they wanted to do something with me and Terry and I said, "Yeah." We developed a concept called California Kirana, The West Coast Legacy of Pandit Pran Nath. It coincided with Terry's 75th birthday. We both studied with Guruji. We were looking at different drumming possibilities, and Talvin caught wind of it and said, "Can I join? I've been learning about Pran Nath and this would be great. Terry said, "I've heard the name, but don't know the music. Let me go check out some stuff on YouTube." I knew about Talvin, but wasn't familiar with his electronica stuff. So, we vetted Talvin electronically over the Web, had a couple of great talks with him on the phone and then made arrangements for him to come out here to Northern California in August 2010.

We headed up to Terry's ranch to prepare in the way only Terry can, which means a lot of playing and eating. We got to know each other, went down and hung out on the river, and the personalities really blended. Talvin is incredibly sweet and really curious about everything, musically speaking. Terry's very knowledgeable about Indian music and a great student of Pran Nath's and knows many compositions in the old style. After we hung out and got to know each other well, we reappeared in Padova, Italy for a couple of days of rehearsal and then went on a really wonderful tour in which we played concerts, hung out, practiced, learned, and took care of each other. It was a rare and precious time. It would be great to get into the studio with the two of them and record some fun stuff.

AAJ: Describe the focus of the trio.

AAJ: Describe the focus of the trio.GB: Everything I've done with Terry is based around his compositional concepts. He's a brilliant pianist and composer. He sets the tone. Terry is most comfortable playing his music. That being said, he was graciously playing "Taj Express" from Lasting Impression, which was pretty cool, because it's a bit of a complicated thing. We focused a lot on some real raga-based things, including old khayal-type compositions, in which Terry is singing khayal pieces and chording them in an inside raga way, and sometimes in an outside aggressive way with exotic keyboard sounds, as well as piano and tabla. It was really rooted in the concept of Indian classical vocals, but then we would also do a lot of his instrumental pieces too.

Terry and I have been playing together since the early '80s, so I know a lot of his repertoire. He's very comfortable with saying "We played this piece 18 years ago, so we don't have to rehearse this." [laughs] His pieces are long, and many are complex, so it's very exciting and challenging for me to play with him. Sometimes, I'll be standing in front of hundreds or thousands of people with Terry and will have to play something I've never heard before. With Terry, if we played something amazing last night, we're sure as hell not going to play it the next night, because we're afraid we might try to play it the way we did the night before. We would be attempting to "re-create," rather than being in the moment. So, we have to do something else. We're always scratching around and looking for magic.

AAJ: How did you first encounter Riley?

AAJ: How did you first encounter Riley?GB: My first encounter with Terry was in 1979. I had just come out to California and got a gig playing at Pasand, a defunct South Indian restaurant in Berkeley. They paid me $15 a night and all I could eat [laughs]. I was playing with Lisa Moskow, a sarod player and student of Ali Akbar Khan, and Tor Dietrich, a tabla player who used to play with the Diga Rhythm Band. One day, Terry came into the restaurant to eat and left a huge $5 tip, which was mind-blowing [laughs]. That was the first connection. My wife Emily was also a student at Mills College, where she was studying with Terry and Pandit Pran Nath. Emily is a trained musician and composer who works more as a theater producer and writer today.

We went to India in 1980 and stayed in New Delhi, studying with a student of Guruji. One day, Guruji came over and we connected right away on a number of levels. He had a heart attack in 1979 and was just recovering, so he was quite fragile and needed certain food cooked for him. I cook well, so I became his cook. And before going into music, I was pre-med and worked for several years with a pediatric cardiologist, so I knew a bit about medicine and cardiac issues. So, I was kind of like his baby doctor [laughs]. I'm also a good masseur and he liked my massages. I can also sit quietly. All of that combined to make a guru very happy. We became friendly very quickly. We were in India, so there wasn't a lot of rigmarole around him like there was when he was here in the States.

Terry came to India to visit Guruji in 1980, which he did regularly. That's where I really got to know him. We stayed there for a year and then Terry went back to California. When I came back, we started doing a little bit of playing. We hung out and I did some traveling with Guruji, Terry and Lamonte Young as their cook. I would take care of things in general, as well as study. By the mid-'80s, Terry began inviting me to play more frequently. We started touring together in a trio with Krishna Bhatt. He took me very early on to Italy for a week and it was a heavenly thing. I learned a lot about intuitive playing from Terry, including how to listen to somebody's thoughts on stage and what's involved in responding to that. He was and still is a big influence on me.

AAJ: At what point did you first become fascinated by Indian music?

GB: It pretty much took a huge hold as soon as I heard it. The first Indian music I heard was probably when I was in high school, on George Harrison's Concert for Bangladesh (Capitol, 1971) record, but I didn't get it at the time. I didn't hear it again until I was a student at the New England Conservatory of music, where I encountered a sitar-playing professor named Peter Rowe. He was a student of Nikhil Banerjee's and had just come back from living in India for six years. He was an American guy, but very Indianized. He was married to an Indian woman and came to school wearing a shawl and smoking Beedies.

During this period, around 1976, I took Peter's course, which offered a survey of Indian music—just on a whim. It was like fireworks going off in my head. I'd go to the listening library and put on Ali Akbar Khan, the Dagar Brothers, and Hariprasad Chaurasia, and it blew my mind the same way John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley were blowing my mind. That's when I started to say "How can I play 'Rag Yaman' on saxophone?" That same year I met my wife, who came floating through Boston. She then floated out to California and ended up at Mills College, where Terry Riley and Pandit Pran Nath were. She said, "You have to come out to California. It's amazing." The rest, as they say, is history.

AAJ: Have you ever had to deal with the vibe of people perceiving you as a "Caucasian interloper" in a sacred set of musical traditions?

GB: I've never experienced that in India, ever, but I have wondered if there might some perception in the States of the idea of "cultural expropriation." I play this music because of the way it has touched my soul and because of the relationships I have been fortunate to develop with so many extraordinary Indian musicians. These musicians have been my guides and mentors and have encouraged my work. I don't know what would be a more culturally appropriate music for me. Would I be genuine if I was playing Klezmer music or bebop or '60s swing music like Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis? When became serious about playing saxophone in 1976, I started hearing Indian music and it intrigued me.

I tried to figure out how to play ragas in the same way I was trying to figure out how to play jazz. "What was Charlie Parker doing?" and "What is Hariprasad Chaurasia doing?" were questions I pondered. All of it was pretty unknown to me, but there were things in both realms that drew me to them. My involvement in Indian music came through my relationships with Indian musicians. As I mentioned, I was incredibly dear friends with Krishna Bhatt. He was an important teacher and a key reason for why I play Indian music. I would sit with him, hang out and drive up to Terry Riley's place and get high together. Whatever we did musically was part of our friendship. My other deep relationship was with Pandit Pran Nath. We had a deep, real relationship. I never thought "Oh man, I can take this form of music and turn it into something that will give me a career." That was never anything I anticipated.

Oddly, I have some ability to travel around the world and perform because of my relationship with Indian music. India is the country where I receive the most appreciation for what I've done. If I play something in the States based on "Raag Charukeshi," nobody knows what that means. If I do it over there on saxophone, even when I'm just practicing, someone understands it. I was doing a gig in India once and was warming up backstage. A Rajasthani Qawwali singer came into the room and just started singing with me. It blew his mind to hear an instrument he wasn't particularly familiar with playing a scale he was very familiar with. So, over there, unless something is going on behind my back, I have genuinely received a lot of positive feedback on what I do. I've endeavored to write music that is attractive and interesting for an Indian musician to play. So, it makes sense to me that a lot of Indian musicians have learned pieces of mine. I hope that I have helped to increase the flow of information and interaction between Indian classical musicians and Western improvisers.

Oddly, I have some ability to travel around the world and perform because of my relationship with Indian music. India is the country where I receive the most appreciation for what I've done. If I play something in the States based on "Raag Charukeshi," nobody knows what that means. If I do it over there on saxophone, even when I'm just practicing, someone understands it. I was doing a gig in India once and was warming up backstage. A Rajasthani Qawwali singer came into the room and just started singing with me. It blew his mind to hear an instrument he wasn't particularly familiar with playing a scale he was very familiar with. So, over there, unless something is going on behind my back, I have genuinely received a lot of positive feedback on what I do. I've endeavored to write music that is attractive and interesting for an Indian musician to play. So, it makes sense to me that a lot of Indian musicians have learned pieces of mine. I hope that I have helped to increase the flow of information and interaction between Indian classical musicians and Western improvisers. AAJ: Do you connect with Indian music at a spiritual level?

AAJ: Do you connect with Indian music at a spiritual level?GB: I think I do, but I don't subscribe to any particular religion. My family is Jewish and that's culturally interesting and important to me. I think there are good messages in a lot of the good books of the different religions, but I think there are a lot of really big problems with organized religion. I understand why people are attracted to it, because it gives them a sense of purpose. My guru was very deeply spiritual. He was raised a Hindu but worshiped as both a Hindu and a Muslim. He would do Pooja every day, but he would say the names of both Allah and Bhagwan. He was very Sufi in that way. He was raised a Hindu Brahman and ran away from home at a very young age and took up with a Muslim music teacher.

So, I've seen how music and musicians have been able to cross all sorts of boundaries. At the end of the day, I would say that I'm a humanist musician. One of the things music is for me is a form of personal study and exploration. I love performing, but it's just as thrilling to practice too. It can make me feel just as good if I feel I learned or saw something I hadn't experienced before. Writing music is a magical thing. Sometimes I think I haven't written that much music, but I look over at the shelf and see a bunch of CDs I've put out. Writing is so interesting because you have notes and sounds, and then you decide "Okay, I'm going to coalesce them into a piece of music." And by performing that piece, you breathe life into it, so it's a spiritual practice. You're penetrating into the mysteries that surround us and trying to find the things that connect us together.

Selected Discography

Elements, Elements (Earth Brother, 2011)

George Brooks Summit, Spirit and Spice (Earth Brother, 2010)

Steve Smith, George Brooks and Prasanna, Raga Bop Trio (Abstract Logix, 2010)

George Brooks, Summit (Earth Brother, 2002)

George Brooks, Night Spinner (Moment Records, 1998)

George Brooks, Lasting Impression (Moment Records, 1996)

Photo Credits

Pages 1 (Brooks), 6: Irene Young

Pages 1 (Elements), 2, 4: Courtesy of George Brooks

Page 3: Stuart Brinnin

Page 5: Gerry Walden

Tags

George Brooks

Interview

Anil Prasad

United States

Kai Eckhardt

Fareed Haque

Zakir Hussain

Steve Smith

Trilok Gurtu

Prasanna

Terry Riley

Talvin Singh

Larry Coryell

anthony braxton

Etta James

randy brecker

Michael Jackson

Jimi Hendrix

John Coltrane

Cannonball Adderley

Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis

Charlie Parker

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.