Home » Jazz Articles » Rediscovery » Five Classic ECM Titles in High Res

Five Classic ECM Titles in High Res

In fact, along with its attention to sonic clarity, breadth and depth, ECM has always been a label intent on pushing the boundaries of what music can be, right from its inception. With Eicher at the helm the label has built a reputation, across a discography of well over a thousand recordings, for releasing music of such consistently high quality that it's one of but a few—and, truly, none of the others possess the longevity, discographical size and/or broad musical continuum—where fans buy new releases sight unseen/music unheard because of their intrinsic trust in the label. Even if the album is from an artist they've not heard before, chances are that once they've heard it most label fans will be glad they did...even if it's not necessarily something to which they'd have otherwise paid attention.

It's also a label unprecedented in the lion's share of its releases being produced by a single person: Eicher. The subject of "The ECM Sound" and what it really means has been debated for almost as long as the label has been around. The certainties? There are no stock reverb settings; and the label has used so many studios and engineers over the decades that it isn't a particular room sound or the person manning the board alongside Eicher. The best and closest way to articulate what the ECM Sound is? A reflection of Eicher's musical aesthetic, which can be reduced to some minimal concepts like "less is more" and the value of space...along with an approach to producing records where every note, from its first—perhaps sharp, perhaps muted—appearance to its final fade to black, with every moment in between, as clear as a bell, even when buried deep in the mix.

But even those descriptors are superficial, at best. What makes ECM recordings so recognizable is something far more complex; any attempts to reduce its qualities to simple terms invariably waylaid by the many easily identifiable exceptions. Those who have followed the label for decades (or even those who've come to it more recently) know some of the touchstones that help render an ECM album instantly recognizable (beyond the five seconds of silence that preface every album since the '90s); but what those touchstones actually are can be the subject of heated debate. An enigma, then, albeit one that is still, somehow, uniquely identifiable.

Across the span of nearly five decades, ECM has released music in a variety of formats, from its original vinyl (and oh, how beautiful and clean were those early German pressings!) through the cassette tape years and, finally, into the digital world with the advent of CD. While there have been a very few exceptions, what's been remarkable about ECM is how well it weathered the early CD years and less than stellar analog-to-digital (and vice versa) conversion that was in its relative infancy, often resulting in albums that were clean, yes, but also brittle and lacking in warmth and depth. Indeed, when looking back at earlier recordings collected in the label's Old and New Masters Edition reissue box sets, such as 2013's Paul Motian, Charles Lloyd Quartets and Jack DeJohnette Special Edition boxes, it turns out that ECM has rarely remastered the original digital masters, unless music that has never before been released on CD is being included.

ECM's pristine sonics and lucent transparency rendered it ideal for the move to CD, where the inevitable ticks and pops that began to emerge on well-played vinyl were no longer a problem—particularly appropriate for a label whose motto was, at one point early in its lifetime, "The Most Beautiful Sound Next to Silence." If ECM recordings have been almost unmatched in their crystalline pellucidity at CD's lower byte size and sampling rate (16-bit/44.1KHz), how would they sound in higher resolutions?

Of course, simply presenting a recording in higher resolution doesn't guarantee anything. The words "digitally remastered from the original master tapes," when applied to poorly remastered albums, still lead many into believing they are getting a superior version of a well-loved album. Instead, they discover that, amongst other things, the new master has been heavily compressed, robbing music of important characteristics including dynamics, sonic verisimilitude and a fuller, three-dimensional soundstage. And so, just like a poorly remastered album, being reissued in a higher resolution—whether it's 24/44.1 or 24/192—doesn't necessarily mean the reissue will be worthwhile. It all depends on who did the mastering—and what they had to work with.

That said, the same "brand loyalty" that has garnered ECM a legion of loyal fans over the decades for its music and sound quality is worth considering when it comes to digital downloads of higher resolution music. And, sure enough, ECM's increasingly vast catalog of high resolution releases—both new albums and older titles—sound as wonderful as might be expected. If their vinyl and CD releases are defined by clarity, transparency and a broad soundstage, when ramped up to higher resolutions—especially increasing the byte size from 16 to 24 bits—the improvements are palpable...though oftentimes subtle as well. Whether listening to nothing but a solo piano on Keith Jarrett's superb Creation or a single (albeit heavily processed electric) guitar on David Torn's staggering only sky (both 2015), or the more fleshed-out sound of Mats Eilertsen's septet-driven Rubicon (2016) or sweeping archival reissues including Gary Burton's Seven Songs For Quartet And Chamber Orchestra (1974), ECM's high resolution reissues have brought even greater clarity, detail and transparency to recordings that already sounded like they couldn't get much better. Except, clearly, they can.

Of course, there are fallacies. While it seems true that going from 16 to 24-bit bytes makes an appreciable difference in sound quality, it's no more empirical than doubling or tripling the sampling rate. It's simply not something that can be measured: just as going to 24 bits doesn't make the sound 50% better than 16, going from 44.1 to 88.2 doesn't make it sound twice as good, nor does going from 24/48 to 24/192 quadruple anything.

First—and while this is a given with ECM, it isn't across the board when it comes to other labels—the actual quality of the mastering job, including the ears and skill of the mastering engineer, matters, first and foremost. The byte size and sampling rate vary based on how the rates at which the original recordings were made, and so some recordings can only be presented as 24/44.1, while others can be released in much higher rates like 24/96 or 24/192. While 24/192 isn't twice as good (whatever good actually is) as 24/96—the differences sometimes so subtle as to be only audible to those with very good ears and, oftentimes, many years of in-studio experience—there's no doubt that moving from 16 bits to 24 and from 44.1 to higher sampling rates can result in a broader, deeper and more delineated soundstage.

It also helps to have good gear. You'll not be able to play anything beyond 24/48 on your IOS device (you'll need a dedicated high resolution player FiiO or PONO for that), but you will be able to play it on your Mac or PC through music library/playback programs like iTunes. But even your Mac limits you, as there's no capability for using a better sound card than comes with most models...though you can improve the sound of your Mac, for example, by getting a good set of speakers, like the Paradigm Shift MilleniaOne CT Multimedia System (a powered 2.1 set of speakers) and using a separate headphone amp/DAC like the OPPO HA-2, which has the capability of substituting for the Mac's internal digital to analogue converter with its own much better DAC. You've got more flexibility for putting in a better quality onboard sound board on your Windows PC, but either way, the quality of your speakers and your DAC are the two things that will most substantially help you get the most out of high resolution music.

This Rediscovery column was created, back in late 2015, with two things in mind: first, driven by a still-ongoing (and still-undiagnosed) health problem that has reduced my written output to a shadow of its former self, the idea of revisiting well-known and well-loved albums was an incentive to write when unable to muster up the juice to review a new recording that required (and still requires) 8-10 listens (plus research) before putting virtual pen to paper; and second, the coincident upgrade to both the speakers and headphone amp/DAC in the office and the acquisition of what is most definitely the best, most accurate and most truthful set of speakers I've ever heard, the 333 stack from Ottawa, Canada-based Tetra Speakers.

Tetra is a somewhat off-the-grid company (i.e. almost never advertizes in audiophile mags and rarely, if ever, works through distributors and/or stores) that has built its customer base largely around word of mouth from musicians, engineers, producers and others affiliated with the music industry, ranging from Dave Holland, Herbie Hancock and David Torn to Peter Erskine, Ron Carter, Keith Richards and Rob Fraboni, all of whom have purchased Tetras (in some cases, like Carter, more than once). Positioned firmly in audiophile territory it's still possible, nevertheless, to get in at the low end of Tetra's product line for $1,500 (CAD) and walk away with an impressive set of 120U "listening instruments," as Tetra prefers to call its speakers.

My Tetra 333 stack hangs off of a Leema Tucana II integrated amplifier, with music fed to it either in hard media form on an OPPO BDP-105D multimedia player or, via the Apple TV box connected to it, from my Mac's iTunes library, which allows playback of music ranging from CD resolution to higher resolutions up to 24/384 and some DSD resolutions as well. I no longer listen to music using lossy compression formats like AAC or MP3.

ECM began releasing high resolution versions of a select number of albums a few years ago, and almost all new releases are now issued in some form of higher resolution, depending on how it was originally recorded. In late 2016, however, ECM released 24/192 editions of five seminal recordings from the 1970s/80s, which are the subject of today's Rediscovery: guitarist John Abercrombie's 1975 leader debut, Timeless; Brazilian guitarist/pianist Egberto Gismonti's 1977 label debut, Dança das Cabeças; expat Canadian trumpeter Kenny Wheeler's second album as a leader for the label, 1978's Deer Wan; also, from 1978, Norwegian guitarist Terje Rypdal's final ECM recording with bassist Sveinung Hovensjø and his first to feature Danish trumpeter Palle Mikkelborg, Waves; and, finally, bassist Gary Peacock's 1982 release with Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek, Polish trumpeter Tomasz Stańko and drummer Jack DeJohnette, Voice from the Past —Paradigm.

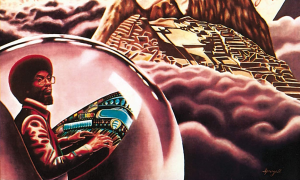

John Abercrombie

John Abercrombie Timeless

ECM Records

1975

As is so often the case with ECM recordings, there are plenty of connections between the five recordings. Garbarek, who appears on Voice from the Past —Paradigm, is also a key contributor to Deer Wan, an album whose four exceptional Wheeler pieces positioned him, early in his leader career, as the composer that singer and ECM recording artist Norma Winstone would call, in a 2001 interview, the "Duke Ellington of our times." Deer Wan also features drummer Jack DeJohnette, who is one-third of the trio on Abercrombie's Timeless, a by-turns atmospheric and frighteningly virtuosic, hard-grooving and spatially ethereal record that also includes ex-Mahavishnu Orchestra keyboardist Jan Hammer on the marquee, in this case focusing largely on Hammond organ but also injecting some of the synthesizer work for which he'd become so well-known.

Hammer also contributes more refined piano touches on three tracks, as well as two compositions to Timeless' six: the initially brightly swinging "Lungs" that turns, mid-stream, into a curious reggae-inflected groove; and the more incendiary "Red and Orange." Abercrombie's sound and harmonic perspective were beginning to emerge from the shadow of early influences like Mahavishnu Orchestra's John McLaughlin, but the guitarist was already making an equally important mark as a writer. Two of his four compositional contributions to Timeless—the ambling "Ralph's Piano Waltz," written for his friend and occasional collaborator Ralph Towner, and the album's strikingly spare, closing title track—quickly surfaced as early Abercrombie compositions destined to become often-covered standards.

Abercrombie's influences may be at their clearest on his ECM debut but, taken together with 1975's first Gateway album, his 1976 duo date with Towner, Sargasso Sea, and his early career milestone, 1977's solo album Characters, not only does Timeless stand on its own as an important beginning for Abercrombie; it's also the beginning of a period of rapid evolution for a guitarist who, to this day, manages to be instantly recognizable without any signature phrases. A motif-driver improviser, it's his touch, his tone, his appreciable harmonic qualities and distinctive lyrical bent that make him one of the most significant guitarists to have emerged in the last fifty-plus years.

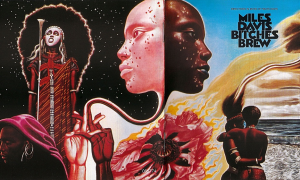

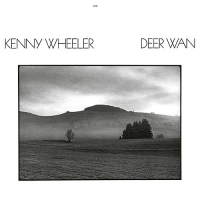

Kenny Wheeler

Kenny Wheeler Deer Wan

ECM Records

1978

Abercrombie joins Jan Garbarek, Jack DeJohnette and bassist Dave Holland as a member of Wheeler's core group on Deer Wan, which also features guest Ralph Towner, contributing his signature acoustic 12-string guitar work to the album's shortest but, in some ways, best track, "3/4 in the Afternoon."

Deer Wan—like Wheeler's leader debut for the label, 1976's award-winning Gnu High—positioned Wheeler as a particularly masterful trumpeter, with an innate ability to combine freewheeling improvisational explorations—impeccably capable of instantaneously leaping huge intervals into the stratosphere—with an intrinsically melancholic approach to melody. But it was his strength as a composer that truly defined this Canadian who left for England in the mid-1950s, living there until his passing in the fall of 2014, at the age of 84.

Whether it's the perfect precision and concision of "3/4 in the Afternoon"—which still manages to find space for a number of meaningful solos in its mere six-minute duration—or the 16-minute "Piece for Five," which opens Deer Wan and, in addition to ensemble-driven soloing from Wheeler, Abercrombie and Garbarek, provides space for lengthy features from both Holland and DeJohnette, Wheeler's writing isn't just immediately recognizable, it's instantly captivating; music that is complex, sweeping and episodic, even as it provides room for collective interpretation.

Despite Wheeler's expat status, there's always been something indescribably British about his writing, and the second side of Deer Wan's original vinyl—containing two roughly ten-minute tracks: "Sumother Song" and the closing title track—is a strong example. Jazz this may be, without question or apology; but in Wheeler's music and improvisational contexts there are hints of the same pastoral nature that imbues the music of fellow Brit, label mate and sometime collaborator John Surman.

Garbarek's work on Deer Wan is as essential to its complexion as those of his band mates. Percussive at times, tartly lyrical at others, Garbarek had already, by even this relatively early stage in his career, established himself as not just a Norwegian star, but an influential saxophonist on an international level. His work here and on Voice from the Past —Paradigm act as a strong representation of his broad ability to mesh into any situation.

Gary Peacock

Gary Peacock Voice from the Past —Paradigm

ECM Records

1982

While there is plenty of freedom to be found on Deer Wan, it's also an album predicated heavily on compositional form; Peacock's fourth album as a leader for ECM not only broke the mould of earlier records instrumentally—two piano trio recordings, 1977's Tales of Another and 1980's Shift in the Wind; as well as the largely solo bass record, 1979's December Poems (which, coincidentally, features Garbarek as the sole guest on two tracks)—it also provided an alternative to Wheeler's form-heavy work; compositions that are, instead, sketches...jumping-off points for collective freeplay.

Not that Peacock's Voice from the Past —Paradigm is light on melody; not unlike Ornette Coleman, the contexts may often be "time, no changes" or, more predominantly here, "changes, no time" or "no changes, no time," but that doesn't mean there aren't memorable themes—the one that stays in the memory the most being, perhaps, that of the opening "Voice from the Past."

Throughout the record, Peacock is a dominant force; beyond his writing, his muscular bass work is not so much the anchor here as the fulcrum, upon which all else is balanced. There's a lot of rubato here, and the temperature flows seamlessly from icy cold to searingly hot, with Garbarek and Stańko employing extended techniques to further broaden the sonic potential of a quartet that ranges from serene to explosive. Stańko—whose Balladyna (ECM, 1976) is another early ECM classic that would, no doubt, sound wonderful in high resolution—is a marvel, his tone moving from burnished to guttural, his connection with Garbarek so empathic that it would be used again, years later, on the more eminently accessible, less open-ended 2005 label debut of drummer Manu Katche, Neighbourhood.

Perhaps the most eminently challenging album of the bunch, Voice from the Past —Paradigm remains a seminal album in the label's discography...significant in its transatlantic nature doing nothing to dilute its clear roots in American jazz but, instead, augmenting it with the alternative cultural DNA from Norway and Poland.

Egberto Gismonti

Egberto Gismonti Dança das Cabeças

ECM Records

1977

It was tempting to suggest that Gismonti's Dança das Cabeças stands alone amongst these five releases, and in some ways it does; certainly it's the only duo (sometimes solo) record. But the truth is, every one of these five recordings is completely different...and yet, somehow, they all feel part of that hard to quantify rubric of ECM Records.

Despite releasing records in Brazil since 1969, Dança das Cabeças remains equally significant as both Gismonti's first ECM release and the first label appearance by percussionist, vocalist and berimbau master Nana Vasconcelos. There may be no connection to the other four releases in terms of players—though both Gismonti and Vasconcelos would ultimately cross paths with many of the label's regular roster, including Abercrombie, Garbarek, Towner, Pat Metheny, Charlie Haden and others—but Eicher produced Dança das Cabeças, as he did the other four, becoming the singular connecting thread. Furthermore, while Timeless was recorded at Generation Sound Studios in New York City, with engineer Tony May joining Eicher behind the board, the rest of the albums, including Dança dad Cabeças, were all recorded at Oslo's Talent Studios with engineer Jan Erik Kongshaug...who may not have been the recording engineer for Timeless, but still participated as the album's mixing engineer. And so, whether from performance, studio, production or engineering perspectives, there are elements common to many...or all...of these five important titles.

Dança das Cabeças's two side-long vinyl tracks are medleys of shorter songs that range from atmospheric evocations of the rainforest to joyful dances and intimate, dark-hued balladry. Gismonti's use of custom nylon-string guitars with eight or ten strings further expands his pianistic approach...something shared with Towner, who would collaborate with Gismonti on the Brazilian's Sol Do Meio Dia (ECM, 1978). There are complex, dissonant pieces juxtaposed with more rhythmically propulsive and melodically accessible passages, driven by Vasconcelos' unique inner clock. Guitars meet hand drums and wood flutes meet berimbau in music that blends the scripted with the completely open...and everything in-between.

It's an album that, for those who first heard it back in the day, was a real game-changed when it came to understanding the music coming out of Brazil. Yes, there was Hermeto Pascoal, making music that was just as far away from bossa nova; but while Pascoal's music has its own unmistakable rawness, Gismonti's more intimate music feels truly born of the rainforest. He has continued to make great music over the years, but in some ways he has never topped the ear/eye-opening Dança das Cabeças.

Terje Rypdal

Terje Rypdal Waves

ECM Records

1978

Which brings us to Waves, Norwegian guitarist Terje Rypdal's first group record since 1975's early career high watermark Odyssey—finally released in its two-disc entirety on CD in 2012's Odyssey: In Studio & In Concert box set—Waves may share some of the previous album's personnel, but the vibe is significantly different. In some ways the album feels how Weather Report, circa 1973/74, might have sounded, had it come from Norway.

While the stereotypical description of "icy Nordic cool" is both overused and abused, it's important to note that before Eicher brought five Scandinavians to international prominence in the early '70s—along with Norwegians Rypdal and Garbarek, bassist Arild Andersen, drummer Jon Christensen and, the only Swede amongst the bunch, pianist Bobo Stenson—that term didn't really exist. It was, in fact, these players who helped define the stereotype, even if that stereotype is a massively reduced version of what it is these five important players actually do.

That said, having been along the massive Molde fjord where Rypdal continues to live to this day, and hearing his heavily overdriven, whammy bar-infused and delay/reverb-drenched guitar work that flows through the opening "Per Ulv..."it's just hard not to connect the two. This is, indeed, music of the fjords, and when Waves' more scripted and more propulsive "Per Ulv" gives way to the eight-minute "Karusell"—initially a pensive duo for Palle Mikkelborg's trumpet and an uncredited voice wailing plaintively in the background but gradually building, albeit at a glacial pace, with the addition of Rypdal's clean-toned guitar, Sveinung Hovensjø's volume pedal-driven electric bass and drummer Jon Christensen's ever-perfect textural injections—and it's even harder not to conjure images of 600 metre cliffs and 600 metres of icy cold mountain water.

There are strange things on Waves, too. The oompa-ing "Stenskoven" manages to march along with Rypdal's quirky melody, leading to a Mikkelborg-played tac piano solo. The title track, on the other hand, continues Rypdal's fascination with layering multiple rubato lines over percussion-driven pulses, in this case Christensen's definitive cymbal work, as the spaces begin to fill with Hovensjø's massive bass and Rypdal's added synth washes. "The Dain Curse" is the Norwegian equivalent of funk...loose, sloppy in all the best ways and, most importantly, completely unpredictable...with Hovensjø's bass, Mikkelborg's horn and Rypdal's guitar intertwining in a free-for-all just barely anchored by the particularly animated Christensen.

Waves is rarely mentioned amongst fan favourites and, looking back at it nearly 40 years later, it seems more than likely the only reason is because of the particularly career-defining albums that surround it. Waves isn't exactly a game-changer for Rypdal; instead, it's more an evolutionary record than a revolutionary one. Still, that doesn't mean, with a group this good and writing so strong, that Waves isn't anything but a stone-cold classic in its own right.

And so, from the rainforest-evoking solo/duo work of Dança das Cabeças and sometimes fiery, sometimes celestial trio work on Timeless, to the spare yet freewheeling sound of Peacock's quartet on Voice from the Past —Paradigm, the icy, electric colors of Waves and the surprisingly big sound of Wheeler's quintet on Deer Wan, these are five albums that not only warrant reissue on the merits of the music—surely the most important criterion—but on the basis of the albums' upgraded sonic qualities at 24-bit/192KHz. It's also an encouraging sign that ECM includes a PDF file with the CD booklet, along with high resolution downloads—a habit that, sadly, has not been picked up by everyone in the digital high res domain yet but, given ECM's attention to design and packaging as well as sound, it's no surprise that the label has done so.

Between the upgraded sound, the relentlessly impressive music and each album's significance in the history of ECM Records, all five records are unequivocally worthy of Rediscovery...and for those of you familiar with any/all of these exceptional recordings, hopefully you'll agree and take a few moments to add your thoughts to the DISQUS comments section at the end of the article.

Tracks & Personnel

TimelessTracks: Lungs; Love Song; Ralph's Piano Waltz; Red and Orange; Remembering; Timeless.

Personnel: John Abercrombie: guitar; Jan Hammer: organ, synthesizer, piano; Jack DeJohnette: drums.

Deer Wan

Tracks: Peace for Five; 3/4 in the Afternoon; Sumother Song; Deer Wan.

Personnel: Kenny Wheeler: trumpet, flugelhorn; Jan Garbarek: tenor and soprano saxophones; John Abercrombie: electric guitar, electric mandolin; Dave Holland: double bass; Jack DeJohnette: drums; Ralph Towner: 12-string guitar (2).

Voice from the Past —Paradigm

Tracks: Voice from the Past; Legends; Moor; Allegory; Paradigm; Ode for Tomten.

Personnel: Gary Peacock: bass; Jan Garbarek: tenor and soprano saxophones; Tomasz Stańko: trumpet; Jack DeJohnette: drums.

Dança das Cabeças

Tracks: Medley #1: Quarto Mundo #1, Dança das Cabeças, Aguas Luminosas, Celebreção de Núpcias, Porta Encandata, Quarto Mundo #2; Medley #2: Tango, Bambuzal, Fé Cem Faca Amolada, Dança Solitária.

Personnel: Egberto Gismonti: eight-string guitar, piano, wood flute, voice. Nana Vasconcelos: percussion, berimbau, corpo, voice.

Waves

Tracks: Per Ulv; Karusell; Stenskoven; Waves; The Dane Curse; Charisma.

Personnel: Terje Rypdal: electric guitar, RMI Keyboard Computer; ARP synthesizer. Palle Mikkelborg: trumpet, flugelhorn, RMI, tac piano, ring modulator; Sveinung Hovensjø; Jon Christensen: drums, percussion.

So, what are your thoughts? Do you know this record, and if so, how do you feel about it?

[Note: You can read the genesis of this Rediscovery column here.]

Tags

John Abercrombie

Rediscovery

John Kelman

ECM Records

Manfred Eicher

charles lloyd

Jack DeJohnette

Keith Jarrett

David Torn

Mats Eilertsen

Gary Burton

Dave Holland

Herbie Hancock

Peter Erskine

Ron Carter

Keith Richards

Egberto Gismonti

Kenny Wheeler

Terje Rypdal

Palle Mikkelborg

Gary Peacock

Jan Garbarek

tomasz stanko

norma winstone

duke ellington

Mahavishnu Orchestra

Jan Hammer

john mclaughlin

Ralph Towner

John Surman

Ornette Coleman

Manu Katche

Nana Vasconcelos

pat metheny

Charlie Haden

Hermeto Pascoal

Weather Report

Jon Christensen

Bobo Stenson

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.