Home » Jazz Articles » Rediscovery » Miles Davis: Bitches Brew

Miles Davis: Bitches Brew

Miles Davis was quite a fella; few today can dispute his gargantuan presence in 20th century music. He shared the insatiable, dionysian genius of that other creative giant, Picasso. By the 60's Miles had already altered the currents of jazz twice...

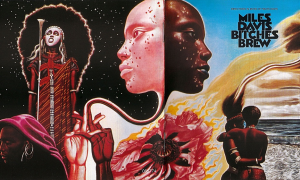

Miles Davis was quite a fella; few today can dispute his gargantuan presence in 20th century music. He shared the insatiable, dionysian genius of that other creative giant, Picasso. By the '60s Miles had already altered the currents of Jazz twice: Re-introducing melody and space to the then busy-bee soloing of the be-bop era, with his appropriately named Birth of The Cool in 1950, and freeing Jazz from its ironically rigid chord-obsessions by spearheading modal Jazz, in what some have called the perfect sonic event, A Kind of Blue (1959). But Mr. Davis didn't know about standing still. It was the late Sixties, Rock was hitting its second mighty crescendo; everybody and their aunt were opening the doors of perception; and sex was tearing off its clothes. Times were stimulating. Miles was with a young beaut called Betty Mabry (soon-to-be Davis), whom Miles had recently pedestalled as his central muse, with the sonic gorgeousity of '68s Filles De Kilimanjaro. Mrs. Davis—yes, that Betty Davis, underrated funk maestress of the criminally overlooked album 'They say I'm different' (1974)—was very much of-the-scene at the time, and introduced Miles to the psychedelic punch of Hendrix and Sly & The Family Stone. The deal was sealed. Jazz didn't know it yet, but a bomb was about to go off, ironically cued by the hush of '69s In a Silent Way.

At the time of recording, Jazz was considered an art of the acoustic instrument. The handful of jazzbos who dared explore electricity were seen as musicians using gadgets to disguise obvious lack of skill and finesse. Electric instruments were taboo, a vulgar crutch. Having tentatively insinuated electricity into 1968 recordings Water Babies and the aforementioned Filles, Miles finally shrugged off the purist's glare with In a Silent Way, a fully electric silence that preambled Bitches Brew. But 'Brew' is a beast unto itself. AT LEAST two drummers, two bassists, and two horns are juggling sound at any given point in its time-space, resulting not in cacophony, but blisteringly detailed sonic texture. Interestingly, the impression Bitches Brew leaves in hindsight is that of storm, and slow-motioned explosions; but on actual listening, the stretches of sound are for the most part laid back. There are many bursts, many slashes of fever—especially in John McLaughlin's staccato-pathic fretwork, which suggests the scrawls of mechanical arachnids—but, ultimately, Bitches Brew doesn't flaunt its energy, its potency. Most of its space is a lazy stretching of musculature.

One of the first albums to hint at what would become Fusion and Jazz-rock—certainly the most influential—Brew had rock fans' jaws clanking onto the floor. Mclaughlin was a guitar revelation, and Miles showed that jazz could do fire-and-brimstone as well as any stadium-straddling rock outfit. Also influential on the yet-unborn Electronica movement, Bitches Brew is a crackling meditation more than it is an album—as ambient as Aphex Twin's Selected Ambient Works vol.2, only an ambience of storm. Its production was also phenomenal, opener "Pharaoh's Dance" alone contains 17 edits, with frequent loops and cut 'n' pastes—unheard of at the time—producer Teo Macera wielding the studio like an instrument in itself. Turbulence shaking hands with chill. A darkly dazzling masterwork.

This article was first published in Muse magazine.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.