Home » Jazz Articles » Film Review » Salvation through rhythm: Max Roach—The Drum Also Waltzes

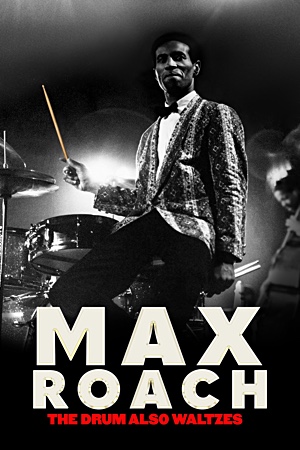

Salvation through rhythm: Max Roach—The Drum Also Waltzes

Courtesy Beuford Smith

If he didn’t have the drums, he would have picked up guns.

—Daryl Keith Roach

Max Roach—The Drum Also Waltzes

Max Roach—The Drum Also Waltzes Directed by Sam Pollard and Ben Shapiro

PBS American Masters

2023

Anyone who enjoyed the recent Wayne Shorter documentary Zero Gravity might also dig this—a more conventionally structured but equally fascinating look at the life of Max Roach. Filmmaker and interviewer Sam Pollard began making it in October 1987, then—for reasons which are not explained—left it alone for years before resuming again at some point after Roach's death in 2007.

It has been worth the wait. The Drum Also Waltzes is absorbing. In terms of technical quality, the edit job is seamless, although the footage from the '80s is no better than a home movie. But it includes interviews with Roach and his onetime wife Abbey Lincoln (who died in 2010), plus concert material with his late percussion ensemble M'Boom. There are also many more recent, professionally shot interviews with all five of his children, plus the likes of Sonny Rollins, Quincy Jones, Abdullah Ibrahim, Randy Weston... it's an incredible roll-call of the jazz aristocracy, but then who wouldn't want to be involved in a film about the equally great Max Roach?

The obvious attraction of such a project is that Roach was at the centre of so many significant post-war movements in jazz—although not its electrification in the early '70s: he remained wedded to acoustic music for his entire career, unless we include his involvement in early rap a decade or so later, when he accompanied his godson Fab Five Freddy on gigs at The Kitchen in New York. The justification for that, if needed, was that he saw it as a new direction for Black music to go in, and of course it was all about rhythm too.

There are plenty of insights along the way. Music, for the young Max Roach, represented the kind of "salvation" for Black kids like him that sports are today. He knew early on that playing drums was what he wanted to do. Archive film shows him in his prime, playing at express-train tempos while remaining almost immobile behind the kit. It was something he had learned from playing with Charlie Parker and Miles Davis. He reveals that Bird would always start a gig with the fastest tune of the night, and so he and Miles would have to "practice all day to get ready for this gentleman."

That early experience affected his entire attitude toward music, treating it as art, always searching for "the next thing" and never interested in looking back. As Quincy Jones points out, the goal for these jazz musicians was to get to a place where "they did not just have to entertain, they wanted to be an artist just like Stravinsky." Sonny Rollins considers that Roach had more finesse and polish than his nearest rival Art Blakey who, he says, was more "elemental," more African in his approach.

One strength of this documentary is that it does not shy away from Roach's demons. For Rollins, the hideous death on the Pennsylvania Turnpike of Max's musical soul mate Clifford Brown still seems raw: "Brownie was like a little angel—how could something happen to Brownie?" It pushed Max into a hellish despair which ended his marriage and very nearly his career. Trombonist Julian Priester recalls how he was mid-solo at a gig at Pep's Lounge in Philadelphia one night when the drums suddenly stopped and Max started climbing over the kit towards him with evil intent. As Daryl Roach, his son, remembers, "He said if he didn't have the drums, he would have picked up guns."

Max's famous romance and marriage with Lincoln calmed him down for a while, as the two of them embraced the cause of Black liberation long before most other artists. The trigger was the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre in apartheid-era Johannesburg when white policemen murdered 69 Black people during a protest demonstration. Roach and Lincoln equated it with the brutal repression of the Civil Rights struggle going on at home. The result was the banned-in-South-Africa album We Insist! Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite (Candid, 1961), although the arguments that ensued over it between Roach and lyricist Oscar Brown Jr. are not mentioned here.

In fact, quite a lot is missing from the story, including what most jazz musicians would consider important in Max Roach's life: the revolution in drumming that he instigated with Kenny Clarke, for example—the use of the ride cymbal to keep time; likewise the recording of "Woody'n You" with Dizzy Gillespie and Coleman Hawkins, which some consider the first ever bebop record; or the famous 1953 Jazz at Massey Hall concert in Toronto with Bird, Dizzy, Charles Mingus, and Bud Powell, often referred to as the greatest jazz concert of all time; or the iconic Duke Ellington trio album Money Jungle (United Artists, 1962), featuring him and Mingus. In fact, one finds the complete absence of Mingus from the film a little strange.

However, the filmmakers have limited themselves to 82 minutes (in contrast, say, with the three-part Shorter documentary), so of course there had to be compromises.

Roach's career was often tempestuous, but in later life his characteristic rages seem to subside. He takes on a professorship at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and enjoys the company of the other artists and intellectuals he mixes with there. And even in his darkest moments, Max Roach was always himself. "He wasn't trying to be anything—he was already it," explains Harry Belafonte.

Towards the end of the film there is a sweet scene of him working with a roomful of fascinated young Black schoolchildren. Seated behind the drums, he sings them a relatively complex rhythmic pattern and tells them where to clap, and of course they all get it right first time.

Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes (PBS American Masters) is available until November 3, 2023.

Tags

Film Review

Max Roach

Peter Jones

dir. Sam Pollard, Ben Shapiro

Wayne Shorter

Abbey Lincoln

M'Boom

Sonny Rollins

Quincy Jones

abdullah ibrahim

Randy Weston

Charlie Parker

Miles Davis

Art Blakey

Clifford Brown

Julian Priester

Kenny Clarke

Dizzy Gillespie

Coleman Hawkins

Charles Mingus

Bud Powell

duke ellington

Harry Belafonte

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.