Home » Jazz Articles » Live Review » Montreal Jazz Festival: Days 7-9, July 7-9, 2009

Montreal Jazz Festival: Days 7-9, July 7-9, 2009

Rocksteady: The Roots of Reggae

Charlie Haden Family and Friends / Bill Frisell Quartet

Van Der Graaf Generator / Ornette Coleman

Festival International de Jazz de Montreal

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

July 7-9 2009

Every year the Festival International de Jazz de Montreal (FIJM) hosts a number of free outdoor concerts, Grand Soirés, that go beyond the already outstanding day-to-day programming at the festival's seven outdoor stages. In past years, performances including Pat Metheny's final show of The Way Up tour in 2005, Seun Kuti's Afrobeat performance at the 2007 FIJM and rapper Bran Van 3000's booty-shaking spectaclea at the 2008 edition brought in crowds in excess of 100,000. The opening event of this year's 30th anniversary FIJM saw the legendary Stevie Wonder attract well over 200,000 people to the festival's newly relocated Scene GM stage.

This year the Scene GM stage, on the new Place des Festivals grounds is augmented by Scene Rio Tinto Alcan stage, at the old Scene GM location on the perpendicular St. Catherine Street. With two large stages possessing the capacity to put on larger-than-life shows and draw large crowds, instead of the old model of three big events—one the opening evening, one on the transitional mid-festival day and one on the closing evening—there are no less than nine shows taking place on seven days of 13 days this year (12 days, really, with the 13th being the Wonder show the night before the official festival began). Ranging from Patrick Watson and Ben Harper to Jesse Cook and a live performance to celebrate the release of the movie, Rocksteady: The Roots of Reggae, there's a little something for everyone, and an opportunity to experience a festival that should be the model for festivals worldwide when it comes to crowd control.

While most festivals utilize fences, private security companies and even the police to manage large crowds at outdoor events, FIJM uses, as Vice-President/CEO André Menard said, "yellow ropes and mostly young women with yellow shirts and red flashlights." With the city of Montreal embracing its festival like no other, even with what seems like minimal security there has never been a problem at the festival— although there are security cameras throughout the grounds in the unlikely possibility of trouble. Instead, even when there's over 100,000 people on the Place des Festivals grounds—drinking and, in the case of the Rocksteady show, a little more—it's party time, with everyone there to experience the sounds along with being with people who have come for the same reason: to enjoy good music and have nothing less than a great time.

Chapter Index

- July 7: Le Grand Soirée: Rocksteady: The Roots of Reggae

- July 8: Charlie Haden Family and Friends

- July 8: Bill Frisell Quartet

- July 9: Ornette Coleman Press Conference and an Unexpected Passing

- July 9: Van Der Graaf Generator

- July 9: Ornette Coleman

- Festival Wrap-Up

July 7: Le Grand Soirée: Rocksteady—The Roots of Reggae

The day was cloudy, and rain not only threatened: it came down about 90 minutes before the large troupe putting on the Rocksteady show hit the stage. But as the skies cleared after about 15 minutes and the grounds dried, the crowd began pouring in until least 100,000 people were on hand by the time the show began at 9:00 PM.

The beer flowed freely, and smell of ganja pervaded much of the grounds; this was, after all, a rocksteady show, the musical progenitor to reggae. Large plumes of smoke could be seen rising above the crowd throughout the Place du Festivals grounds, and it was a little intoxicating just being there. But when the large group took the stage for Rocksteady: The Roots of Reggae, beginning with Leroy Sibbles singing the get-the-party-started classic, "People Rocksteady," the few people sitting down around the grounds were up in an instant, grooving to a crack band that included guitars, bass, drums, percussion, keyboards, horns and backup singers for the stars of the show, Sibbles, Stranger Cole, The Tamlins, Marcia Griffiths and Judy Mowatt (two of reggae legend Bob Marley's Three Little Birds).

Upbeat and lively, even when Griffiths and Mowatt delivered a soulful version of the Vincent Ford classic, made famous by Marley, "No Woman, No Cry," it was taken to an even higher level when percussionist Bongo Herman took center stage, not asking, but demanding that everyone in the crowd with a lighter, a camera or a cell phone light it up in tribute to the late Michael Jackson, who was buried that day in Hollywood's Westwood Park Memorial Cemetery. It was a powerful moment, as thousands of people created small lights that, collectively, lit up the grounds.

But the moment passed and it was back to partying, as the ensemble delivered hit after hit—often songs that so iconic that it was possible to remember all the words, even without hearing them for decades. From Leroy Sibbles' "Equal Rights" to Stranger Cole's "Koo Doo Doo," Judy Mowatt's "Silent River" and Hopeton Lewis' "Take It Easy," the crowd was treated to a Jamaican history lesson told in music and lyrics. The singers also introduced many of the songs, contextualizing them with their own experiences and making them truly vivid and real.

Rocksteady: The Roots of Reggae, the documentary which traces the late-'60s emergence of a music that blends ska, R&B and soul into a trendsetting predecessor for reggae's appearance a few years later, is also being shown in Montreal, running from July 4 through July 12, with some screenings featuring French subtitles, others not. And what better way to celebrate the world premiere of a landmark film which covers the socio-political problems that took place in Jamaica following its secession from Great Britain in 1962, creating—as so often happens—a unique musical response, than to put on a captivating live performance with some of the genre's remaining leading lights?

It was a memorable evening filled with iconic songs that have become part of the soundtrack to human history. But for most people in the audience, it was simply a chance to party and dance. And party they did, hard, and for nearly three hours.

July 8: Charlie Haden Family and Friends

Those only familiar with Charlie Haden's inestimable work in the jazz sphere may be surprised to know that the iconic bassist started out as "yodeling Charlie" with the Old Haden Family Show, a radio show from the late '30s when he was only two years old. Still, as the bassist explained to a near-capacity crowd at his July 8, 2009 performance at Place des Arts' Théâtre Maisonneuve, that his ties to country music have always run deep—and how he's been an inspiration for use of the music in ways that could never have been predicted.

During the recording session of Ornette Coleman's "Ramblin'" for the saxophonist's groundbreaking Change of the Century (Atlantic, 1960), the bassist quoted the traditional barn-burner, "Old Joe Clarke" in his solo. When Ian Drury, of infamous British '70s new wave group Ian Drury and the Blockheads, heard it, he lifted Haden's solo to create the melody for the hit song "Sex & Drugs & Rock and Roll." Clearly music has a strange way of getting around.

This was just one of the anecdotes Haden provided at an uncharacteristically not jazz performance by the bassist at FIJM. Performing music from Rambling Boy (Verve, 2008) with the Haden family including daughters Petra, Rachel and Tanya ("The Haden Triplets) and son Josh, in addition to some heavy-hitting friends including ubiquitous mandolinist/vocalist Sam Bush and banjoist/vocalist Dan Tyminski (a member of Alison Krauss and Union Station), Haden delivered an often touching and instrumentally impressive 90-minute set that provided the opportunity to see the bassist—who also sang back-up vocals on a few tunes with a high, clear voice—at his most open and vulnerable, going back to his roots in traditional folk and country music.

Clearly happy to be sharing the stage with some marvelous instrumentalists and singers, but most importantly with his own family— the pride with which he continually introduced his daughters and sons was heartwarming throughout the performance—Haden took the time to introduce every song from a set that included such country and traditional classics as "Single Girl, Married Girl"—sung by the Haden Triplets with a synchronicity that can only come from siblings—"Ocean of Diamonds," "Rambling Boy" "He's Gone Away" and "Road of Broken Hearts."

Josh Haden sang both Waylon Jennings' "Stop the World" and his own touchingly fragile "Spiritual"—performed instrumentally by Charlie Haden and guitarist Pat Metheny on the classic Beyond the Missouri Sky (Short Stories) (Verve, 1996)—an early highlight. Tyminski, the most identifiable voice in Union Station outside Alison Krauss, sang a number of tunes including his own hit, the traditional "Man of Constant Sorrow," made famous in the Coen Brothers' 2000 film, Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?

Beyond his introductions, Charlie was happy to leave others front and center, but his warm and woody bass remained a clear presence. After an opening instrumental that gave all the players a chance to stretch, Haden introduced the show by saying, with respect to bringing the show to the FIJM, "I've thought a lot about playing this music at a jazz festival, but it's great to see people who just want to hear good music." And good music it was. There were clearly some who didn't read the program notes when they bought their tickets—expecting a jazz show and, upon discovering this was a set of old-style country music, leaving the hall. But they were in the minority, with the rest of the audience remaining for some great, old-time but timeless country music with a bluegrass tinge. Delivered with unassuming sincerity, it provided a clear window into a part of Haden that remains integral to who he is and what he does, whether inside or out of the jazz sphere.

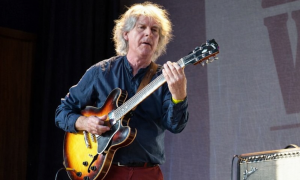

July 8: Bill Frisell Quartet

A popular festival regular for many years, guitarist Bill Frisell brought a quartet of friends old and new to FIJM, blending a variety of musical interests to create a sound that clearly came from the jazz sphere, but expanded far beyond even its furthest reaches. Frisell goes back many years with trumpeter Ron Miles—who played exclusively on the warmer-toned cornet—appearing on Frisell's uniquely configured Bill Frisell Quartet (Nonesuch, 1996), Americana-inflected Blues Dream (Nonesuch, 2000) and ambitiously structured History, Mystery (Nonesuch, 2008). Bassist Tony Scherr—who lives inside and out of the jazz world as an equally compelling singer/songwriter/producer—may not appear on many of Frisell's recordings (his first appearance was on 2004's Unspeakable, also on Nonesuch), but he's been gigging with the guitarist for over eight years. Drummer Rudy Royston is the relative newcomer, but has been playing with Frisell regularly for the past couple years, including a date at the 2007 Ottawa Jazz Festival.

A longtime friend of The Far Side cartoonist Gary Larson, a Frisell show is often a bit like the sonic equivalent of one of his cartoons. Quirky, ironic and often possessing a hint of comic absurdity, Frisell for many years has been mining an improvisational area that's based on structure—sometimes as simple as a repetitive pattern, like the rootsy "Monroe" from Good Dog, Happy Man (Nonesuch, 1999), which this quartet played at a brighter clip, with a hint of Western swing but greater edge and angularity. But by surrounding himself with players who can turn on a dime, he makes every performance fresh and wonderfully unpredictable.

And the strange thing about it all is that Frisell's reputation as a guitarist's guitarist is based on an approach that often eschews delineated soloing, always looking for more musical alternatives to guitaristic grandstanding. Miles, Scherr and Royston received plenty of solo opportunities, but even when Frisell was at the forefront, there was something unmistakably collaborative in the way he worked in and around his band mates. Working with more effects pedals than ever before while rarely using them as frequently or overtly as he has in the past, Frisell altered his tone regularly, from a warm, distinctly clear sound where every note in his uniquely voiced chords could be heard, to more aggressive distortion, a welcome return to a tone he's adopted far less often in recent years.

One of his best performances at FIJM, it seems that Frisell is coming out of a period where he focused on individual ideas—the world music-centricity of The Intercontinentals (Nonesuch, 2003), the roots Americana of Good Dog, Happy Man, the more idiosyncratic composition of This Land (Elektra/Nonesuch, 1994) and History, Mystery and the clearer jazz vernacular of the "East" disc of East/West (Nonesuch, 2005)—now bringing them together into a mélange that's all of them and, at the same time, none of them. An abstract and gradually coalescing introduction led unexpectedly into a lyrical reading of Henry Mancini's often-covered "Moon River," with Scherr taking a lengthy solo while Frisell painted around the edges.

Miles, along with Ralph Alessi, is one of the most undervalued hornists in jazz, and played with a combination of fierce energy and nuanced understatement. He also provided, as an additional front line voice, the chance for Frisell to weave harmonies, colors and melodic counterpoints; freed up, as he was, from being the primary melodic instrument. It gave familiar songs like Frisell's ballad, "Strange Meeting," a deeper harmonic sophistication as the guitarist demonstrated his remarkable ability to take a simple chord and skew it viscerally just by shifting it marginally.

The entire performance had the feel of a completely free exchange of ideas, where the group could, at times, descend into a turbulent maelstrom of unfettered free play. And yet, Frisell's appealing tone, uniquely structured writing, and ability to take a song like the Burt Bacharach/Hal David classic, "What the World Needs Now"—part of a two-song encore that was an unexpected segue from an up-tempo and powerful version of The Intercontinentals' "Baba Drame"—and twist it on its side while respecting the song's essence, kept even the most angular of moments strangely appealing. Frisell has always believed that good music is where you find it, which made his highly interactive performance the perfect dovetail to Charlie Haden's show a couple hours earlier.

July 9: Ornette Coleman Press Conference and an Unexpected Passing

At an early afternoon press conference, where Ornette Coleman was awarded FIJM's prestigious Miles Davis Award, the elliptical free jazz progenitor sidestepped numerous questions about music, and instead focused on larger matters of life and death. "I've lived long enough to appreciate what we as humans try to do and that's raise the quality of life to another level," Coleman said shortly after being presented with the award—a bronze statue of the late Miles Davis, another legend and stylistic forward thinker who, like Coleman, was truly changing the shape of jazz in the seminal year of 1959, when albums including the trumpeter's Kind of Blue (Columbia), Charles Mingus' Mingus Ah Um (Columbia), Dave Brubeck's Time Out (Columbia and Coleman's own The Shape of Jazz to Come (Atlantic) were either recorded or released.

Despite the efforts of the media to talk about Coleman's music, his performance taking place that evening or the concept of risk in his music, he was simply not interested in going there. When asked about improvisation, he alluded briefly to the concept of making mistakes but then added, "I don't really know what a mistake is." But on the subject of life and higher aspirations he had plenty to say. "The concept of life has more to do with words than anything else," he said, closing the brief conference with words that bore special significance to many of the members of the press: "I would like everybody on earth to be happy and not to die."

Sadly, a fine sentiment but one brought home with the sudden passing of Len Dobbin the previous evening, while attending a performance at Montreal's Upstairs Club. Dobbin was more than just a fixture on the Montreal scene for longer than most people can remember; he was, quite possibly, one of the biggest jazz fans in the world, certainly the most passionate advocate of the music to anyone that knew him.

Dobbin wore a number of hats to provide exposure to the music that consumed him from an early age, in his mid-teens. A photographer, writer for Coda, voter in the annual Down Beat Critics Poll, host of the radio show "Dobbins Den," advisor for The Upstairs Club and the reference for Pepper Adams' "Dobbin,'" Nick Ayoub's "Dobbin's Nest" and Oliver Jones' "Len's Den," Dobbin became friends with the many jazz luminaries who came through Montreal, many of them performing at FIJM. He was the recipient of a Masterworks award from the Audio Visual Presentation Trust in 2005, the only jazz broadcaster to win the award to date.

But more important than his many accomplishments was the single passion that dominated his life. His unexpected passing was tragic, of course, but in many ways the circumstances were as appropriate as could be for someone whose passion for jazz was an all-consuming and lifelong love affair: listening to jazz in a club, surrounded by his friends. He will truly be missed.

July 9: Van Der Graaf Generator

With the number of groups reforming after as many as four decades of inactivity, it's a treat to find one that not only is putting out new material—and that, in itself, is rare enough—but one whose current work is every bit as good as anything released back in the day. Britain's Van Der Graaf Generator reemerged in 2005 with a new studio album, Present (Charisma/Virgin, 2005) and a remarkable follow-up, documenting the group's supporting tour, Real Time (Fie!, 2007). Songs like "Every Bloody Emperor" were ever bit as classic as "Man-Erg," from 1971's Pawn Hearts (Charisma/Virgin), proving that VDGG in the 21st Century not only still had it, but was capable of being completely relevant. No throwback this, no releasing a new album, playing one perfunctory tune and then going back to the "golden years" for VDGG; singer/pianist/guitarist and principle songwriter Peter Hammill remains capable of writing the kind of definitive material that possessed all the characteristics of classic VDGG: the raw power; sheer melodrama, grand majesty...and jagged terror.

VDGG was always capable of creating sonic nightmares, largely due to the interaction between organist Hugh Banton and saxophonist/flautist David Jackson. When Jackson left the group after the 2005 tour and the group decided to continue on as a trio, longtime fans were skeptical. Jackson's woodwinds were an absolutely fundamental part of VDGG's dense, turbulent sound; how could the group possibly continue? Well, not only did the group continue as a trio, also featuring drummer Guy Evans, but it released Trisector (Fie, 2008), proving yet again, that it was capable of creating music of this century that fits absolutely within the group's larger body of work.

But could VDGG perform its classic repertoire without Jackson? That was the question when VDGG began touring in support of Trisector last year, and the answer to that question is an unequivocal yes, something that Montreal learned when the group came to Théâtre Maisonneuve for a somewhat shortened but absolutely outstanding 6:00 PM set (Ornette Coleman was to follow at 9:30 PM).

FIJM is known for its attentive and appreciative crowds, but the sold-out audience of die-hard VDGG generator fans surpassed even FIJM's high standards. Giving the trio a standing ovation—the first of many—when Hammill, Banton and Evans took to the sparse stage, was one of the loudest heard at the festival. Making it clear that, as Hammill later said, "we are a modern group and a group with a certain amount of history," the trio launched into the complex "Interference Pattern," with Hammill on piano playing staggering contrapuntal lines across Banton. It was one of three songs from Trisector that occupied the six-song, 70-minute set (plus a 10-minute encore of "The Sleepwalkers," from Godbluff (Charisma/Virgin, 1975)), and possessed everything than defines VDGG.

Evans was always a loose and responsive drummer, but with a bigger sound and even greater fluidity, he's never played better. Banton, with two keyboards and a bass pedal rig that looked like a mad scientist's nightmare, was nothing short of remarkable. Matching Hammill's overdriven and up-tempo guitar riff on "All That Before," his bass pedal work was especially stunning. His feet moving with almost unparalleled speed while, at the same time, moving his right foot seamlessly on occasion to his volume pedal to control the overall level of the keys would have been enough. But he rarely, if ever, even looked at the pedals, all the while delivering a dense wall of sound with his two hands and making it abundantly clear that there are few keyboardists—and that includes more iconic progressive rock players like Yes' Rick Wakeman and ELP's Keith Emerson—who have this kind of command of their instruments. Banton's virtuosity is less overt—VDGG is, after all, not about lengthy solos of virtuosic excess—but he's a virtuoso nevertheless. Neither does he need a vast array of keyboards to fill a group sound and compensate for Jackson's absence—especially on Trisector's epic "Over the Hill," where Hammill began at the mike without guitar or piano, leaving the instrumental work to Evans and Banton alone.

With so many voices aging badly—Peter Gabriel's range slowly narrowing and Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson almost unable to sing at all— Hammill's voice has actually improved with age. Delivering another episodic classic, "(In the) Black Room," originally released on Hammill's solo album Chameleon in the Shadow of the Night (Charisma/Virgin, 1973) (recorded during VDGG's hiatus between Pawn Hearts and its triumphant 1975 return with Godbluff, but really intended as a VDGG song), Hammill's voice has developed a depth and grit that allows him to deliver the material with but one voice, sounding every bit as powerful and large as on record, where he often uses multitracking to create a rich choir of voices.

The set may have been short, but every song was a highlight, with "Childlike Faith in Childhood's End," from Still Life (Charisma/Virgin, 1976), a special high point amongst many, and the set-closer, the boldly majestic but also turbulent and dissonant "Man-Erg," from Pawn Hearts—still arguably the group's finest hour—even stronger. With Jackson's role so dominant on the original "Man-Erg," it was hard to imagine that VDGG as a trio could pull it off, but with Banton layering additional processed organ sounds during the song's harsh, dissonant and nightmarish middle section that alternates between bars of 5/4 and 6/4, Jackson's absence wasn't felt in the least. And the encore, "The Sleepwalkers," was equally impressive; the group managing to tread the line between tightly performed arrangements and a raw, unbridled power that isn't about the sheer volume upon which many groups rely; it's about unfettered passion and Hammill's near reckless abandon, mirrored by the more reserved-looking but equally over-the-edge Banton and fiercely fervent Evans.

After the encore, the audience rose to its feet, demanding a second encore that never came. But at a festival where audience appreciation is truly unmatched, this crowd was as appreciative as it gets—standing, clapping and screaming for almost 10 minutes, as the lights in the theater came up and the roadies began tearing down the stage for the next performance. And dozens of fans remained outside the theater for nearly an hour, enthusing about a show that may not have been jazz (not that it matters, though Hammill has said, in the past, that the group was listening to a lot of '70s electric Miles Davis while recording Present), and may not have been as long as they'd have liked, but will go down as perhaps the most exciting show of FIJM 2009.

July 9: Ornette Coleman

A humble progenitor, Ornette Coleman's place in jazz history would have been assured had he done nothing more than his groundbreaking work of the late-'50s/early '60s, like The Shape of Jazz to Come (Atlantic, 1959) or Change of the Century (Atlantic, 1960). But he went on to innovate his system of "harmolodics" or, as Coleman has described it, musical creation in which "harmony, melody, speed, rhythm, time and phrases all have equal position in the results that come from the placing and spacing of ideas." Over the decades, Coleman has occasionally disappeared from the scene—sometimes for years at a time—but has always come back as fresh and relevant as ever.

With a repeat presentation of the Miles Davis Award in front of a capacity audience at Théâtre Maisonneuve, the 79-year-old Coleman was clearly appreciative but again, in his acceptance speech, remained as cryptic as ever. Cryptic he may have been, and he may have moved slowly, but when he took the stage with his quartet—drummer/son Denardo Coleman, acoustic bassist Al McDowell and electric bassist Tony Falanga—he demonstrated the all the power and creativity were still in full force. Playing seated, Coleman relied largely on his alto saxophone, but he would often pick up a trumpet or violin for relatively brief moments, creating sonic diversity over an often stormy underpinning from Denardo and McDowell. Falanga was especially impressive, using his electric bass more like a guitar, with plenty of chordal accompaniment as well as a counter-voice of long, serpentine and sometimes elliptical lines that mirrored the saxophonist's equally sinuous phrases. McDowell proved to be an encyclopedia of jazz history, swinging hard when necessary but playing with fierce intensity throughout. Denardo played with equal freedom, moving from groove to turmoil in the blink of an eye, all the while managing to work in unison with the rest of the quartet during some of his father's more challenging charts.

Free jazz is not necessarily about working without structure: it's about taking what may be a very sketchy roadmap and using it to explore a broad spectrum of expression. While there was no shortage of hard surfaces and sharp edges in the performance, there was great beauty as well, with McDowell's arco especially singing, and Coleman's alto particularly plaintive on the group's second encore, a brief rendition of Coleman's classic "Lonely Woman." The blues was there too, with a curious and gradually intensifying "Turnaround," and there was even a reference to the late Michael Jackson in the first encore, when Falanga and Denardo went into the driving riff of "Beat It" within a freer context than the late King of Pop could ever have imagined.

Since winning the 2007 Pulitzer Prize, Ornette Coleman's star has once again ascended, with the innovative multi-instrumentalist hitting the road and revisiting some of his extensive back catalog, but with a modern approach that incorporates all he's done over the past 50 years. As a final show to attend at the 30th anniversary of FIJM, it was a strong finish with a legend that is still at the top of his game.

Festival Wrap-Up

With three days left at the 30th anniversary of the Festival International de Jazz de Montreal, there's still plenty of great music to come, including flamenco bassist Renaud Garcia-Fons' three-day By Invitation series, and individual shows by George Wein and the Newport All Stars, Helen Merrill, Robert Glasper, Bill Charlap and Houston Person, Greg Osby and Jean-Pierre Zanella. But over the first nine days of the festival, there's been a particularly strong line-up of musical diversity that's easily eclipsed the festivals' 25th anniversary in 2004.

With a wealth of shows covering a broad range of music, the past nine days have been yet another example of why FIJM is one of the world's largest and most successful jazz festivals. With media staff who make covering the festival both easy and a complete joy; volunteers around the site treating everyone with respect while they handle matters of security in an almost innocuous fashion; and others keeping the large festival grounds clean, the Festival creates a vibe like no other. And one thing the event has proven year-after-year: just when you think it can't grow and get any better, the Festival does something unpredictable and, indeed, does find ways to keep the celebratory occasion at the forefront.

It's always easy to wonder what the next year will bring—how can it improve on an already near-perfect model? History has proven that the Festival International de Jazz de Montreal will not only find a way to do so, but almost certainly already knows exactly how to manage it.

Visit Charlie Haden, Bill Frisell, Van Der Graaf Generator, Ornette Coleman and Festival International de Jazz de Montreal on the web.

Photo Credits

Len Dobbin Photo: Courtesy of the Montreal Gazette

All Other Photos: John Kelman

Days 1-3 | Days 4-6 | Days 7-9

Tags

Festival International de Jazz de Montreal

Live Reviews

John Kelman

Braithwaite & Katz Communications

Canada

Montreal

pat metheny

Stevie Wonder

Michael Jackson

Charlie Haden

Ornette Coleman

Bill Frisell

Ron Miles

Ralph Alessi

Miles Davis

Charles Mingus

Dave Brubeck

Pepper Adams

Oliver Jones

Renaud Garcia-Fons

George Wein

Helen Merrill

Robert Glasper

Bill Charlap

Houston Person

Greg Osby

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.