Home » Jazz Articles » Film Review » Motian In Motion

Motian In Motion

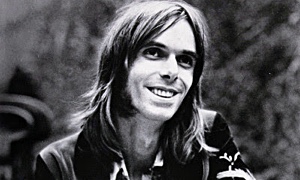

Paul Motian

Paul MotianMotian In Motion

Aquapio Films

2021

There could have been no more apt title for film maker Michael Patrick Kelly's documentary film on drummer, Paul Motian (1931-2011), who buzzes about his New York business—in and out of taxis on the way to and from gigs or the recording studio—with perpetual wind in his sails.

Even when simply chatting with friends, Motian always seems to be in movement. A hug is never far away, and laughter follows Motian the way dust follows Peanuts' Pigpen.

Motian was ripe for the documentary treatment. "Paul turned all the conventional wisdom about playing the drums on its head," states Steve Swallow, one of numerous jazz luminaries who testify to Motian's unique musical qualities, and who help build an idea of the personality behind the drum kit.

Born in Philadelphia and raised in Providence, Rhode Island, Motian first made his name in the Bill Evans Trio of the late '50s and first half of the '60s— a combo still revered today as one of the most influential piano trios in jazz history.

Then, from '67 until '76, Motian played with Keith Jarrett, first in a trio with Charlie Haden and then in the celebrated quartet that featured Dewey Redman. Had Motian hung up his sticks at that point he would still have cast a long shadow in the jazz hall of fame. But as this film makes clear, Motian's driving ambition was to be a leader in his own right.

The genesis of Motian in Motion came about when film maker Kelly met Motian in 1999. To his surprise, Kelly discovered that documentary material on the legendary drummer was sparse. He duly set about filling that void.

Those eagerly anticipating extended performance footage from Motian in Motion will likely be disappointed, as live material is rationed in short snippets.

Fleetingly, we see Motian in the early years with the groups of Bill Evans, Charles Lloyd and Jarrett. There is an all-too-brief glimpse of his long-running trio with Joe Lovano and Bill Frisell, and of his latter-day Electric Bebop Band, but taken together this footage of Motian playing amounts to just a few minutes of the film's total.

That said, a little grainy film that may come as a surprise to some, shows Motian performing at Woodstock with folk singer Arlo Guthrie. Kelly asks Motian if he had any misgivings about playing music that was not jazz, at the epoch-defining festival that attracted half a million souls to Max Yasgur's farm in the summer of '69. "Shit, no!" rebuts Motian. "What for? I needed the money. I needed the work. I had fun. I like cowboy music, man! I wanted to be a cowboy when I was a kid," he retorts with hearty laughter.

Biographical information of a personal kind, however, is also pretty sparing. There is only passing mention of Motian's extended family and their Armenian roots. The impression emerges, rightly or wrongly, of a man so invested in music that there was little time for anything else, jogging through his beloved Central Park aside.

The film's primary focus—and its strength—lies in shedding light on the attributes, musical and personal, that made Motian such a unique and influential force in jazz.

For many, one of the attractions of this most modern of drummers was that he also possessed a very deep connection to jazz's storied past. Quite apart from his stints in the groups of Evans and Jarrett, Motian also played with Oscar Pettiford, Coleman Hawkins and Thelonious Monk. "They were birds of a feather," opines Steve Swallow of Monk and Motian. "They were equally aggressively eccentric."

Another interesting take on Motian comes from Larry Grenadier. "To me, he was almost pre-bebop." The long-time bassist in Brad Mehldau's trio is also quick to dispel any notion that Motian was somehow limited to the role of free-jazz drummer. "When he played in time it was the best time of anybody I ever played with."

It was partly Motian's link to the music's rich past and partly his phenomenal musicality, it seems, that made him such a magnet for young musicians desiring to test themselves.

Chris Potter recounts how, in 1993, he turned down a lucrative tour with Steely Dan just so that he could grab the opportunity that had presented itself to play with Motian. "He brought out our imaginations," says guitarist Steve Cardenas, "and that's the thing I think we're most grateful about."

Motian provides a degree of insight into his key musical collaborations and his musical philosophy, but it is mostly of an off-the-cuff, humorous nature. His tale of the musical catalyst provided by him, Evans, and bassist Al Cotton dropping their pants during a flat, uninspired performance, and another anecdote of a tight-lipped Monk involving Dave Holland, are priceless, though hardly illuminating.

Equally memorable is Motian and Frisell's encounter with a dissatisfied fan who seeks them out backstage at the Village Vangaurd to vent his disappointment at their playing. It would have been easy for Kelly to have left out this scene with their potty-mouthed retorts, but the director's warts 'n' all approach makes for a more honest and enjoyable film.

The most revealing assessments of Motian, however, come from a host of friends who played with Motian and who knew him well: Gary Peacock, Carla Bley, Steve Kuhn, Chick Corea, Jerome Harris, Greg Osby, Anat Fort, Frank Kimbrough, Swallow, Frisell and Lovano—all share their thoughts. A real sense of Motian's authenticity and of his musical bravery emerges from the collage, as does the shared love felt for the man.

Others who pay tribute to Motian include The Village Vanguard's Lorraine Gordon, New York Times jazz critic Ben Ratliff ("He can develop the most lovely idea just with one cymbal and one drum.") and ECM head honcho Manfred Eicher, who was there at the beginning of Motian's career as a recording leader, and at the very end. For Eicher, Motian was essentially "a poetic man."

There is poetry in Motian's unique compositions, in his one-of-a-kind melodies and in the life that he lived, dedicated to his art. And there is poetry too, of a simple yet arresting kind, in Michael Patrick Kelly's heartfelt documentary on the onliest Paul Motian.

Tags

Film Review

Paul Motian

Ian Patterson

Aquapio Films

Steve Swallow

Bill Evans

Keith Jarrett

Charlie Haden

Dewey Redman

charles lloyd

joe lovano

Bill Frisell

Oscar Pettiford

Coleman Hawkins

Thelonious Monk

Larry Grenadier

brad mehldau

Chris Potter

steely dan

Steve Cardenas

Al Cotton

Dave Holland

Gary Peacock

carla bley

Steve Khun

Chick Corea

Jerome Harris

Greg Osby

Anat Fort

Frank Kimbrough

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.