Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Gary Bartz Is Nobody's Jazz Musician

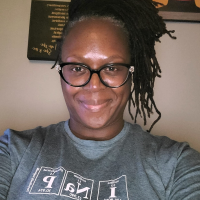

Gary Bartz Is Nobody's Jazz Musician

No two people hear the same way. If you can figure out how you hear, then you'll sound like you. No one else can sound like you, because they can't hear like you.

—Gary Bartz

Born in Baltimore and schooled at Juilliard, Bartz went on to share the stage with some of the biggest names in music like Sonny Stitt, Eric Dolphy, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Max Roach, Art Blakey, and Miles Davis before eventually forming his own group, the NTU Troop, where he blended several genres together to create sounds that reflected the artist he wanted to be. With more than 45 albums as a leader and over 200 appearances as a guest performer, he released Damage Control (OYO Records, 2025) on his 85th birthday (September 26th). The album, his first studio recording since 2013, is the first installment of a trilogy of new music entitled the Eternal Tenure of Sound.

We caught up just before his set at the 21st annual DC Jazz Festival, where Bartz reflected on his roots, his resistance to labels and what it means to compose in the moment.

AAJ: You're originally from Baltimore, MD, but you got your start in New York City. What were those early years like for you?

Gary Bartz: Baltimore was really a big music town, so I really got started there. I sat in with Sonny Stitt when I was 14, at a club called the Comedy Club down on Pennsylvania Avenue ...

AAJ: Was it true that your dad owned a jazz club?

GB: He did, but not until 1960. That same summer, I sat in with Max Roach in a club that was just up the street on Pennsylvania Avenue called Club Casino. I met John Coltrane and Benny Golson at Wagon Wheels, another club in West Baltimore. I didn't know who they were at the time. Benny Golson reminded me later on, "Remember when me and John met you?" (laughs) Baltimore was a big music city. My dad bought the club after I'd already moved to New York in 1958. He had that club for five years.

AAJ: So, that was well after you'd already gone.

GB: Yes.

AAJ: You've been a professional musician for a number of years now. What do you find most interesting about how jazz has evolved?

GB: First of all, I don't use that word.

AAJ: I was going to get to that [laughs].

GB: Music evolves as people evolve. There's always something new. If you're an artist, you're always trying to play something that nobody's ever heard. You're trying to hear the future. That's what we were all trying to do. We didn't want to sound like anybody else. We wanted to sound like us. My theory is that everybody hears differently. It's like a fingerprint. No two people hear the same way. If you can figure out how you hear, then you'll sound like you. No one else can sound like you, because they can't hear like you.

AAJ: True. So, since you mentioned that you don't use the term jazz, do you think of jazz as Black American Music? Do you think there need to be more distinctions made about jazz? There seems to be a growing number of musicians who are rejecting the term jazz. What are your thoughts about it?

GB: It's music. Music is sound, and sounds come from nature. You can name water Perrier or whatever that is (pointing to a generic water bottle), but it's still water. It doesn't mean anything; it's just a way to sell something. We don't have time for that. And if there has to be a name, at least ask us. The older musicians that I knew, like Max [Roach] may have punched somebody in the face over that word. It's a negative word, and negative words bring negative energy. That's why we don't like that word. It's a put-down.

AAJ: What about Black American Music? Is that a fair description?

GB: It's a better name than jazz, but I don't think that's it either. It's music. That's all it is. Beethoven played music. Charlie Parker played music. Why do you have to name it? Miles Davis played Miles Davis music. That's better for me, because he hated that word too.

AAJ: Do you think these labels affect how audiences respond to the music?

GB: I think it's very detrimental. When I'm listening to students play, I'll say, "You're trying to play jazz. You're not trying to play music." I hear the difference. It's a big difference. They'll say, "I want to learn how to improvise." Why? That means you're just making up stuff. It [labeling the music as jazz] is a way to demean us. What we're doing is composing music on the spot. When you hear us play later, we're going to play Charlie Parker's song "Koko." The head that we play is his solo; it's two choruses on "Cherokee." His solo is one of the greatest compositions I've ever heard and he did that right on the spot. They don't think anybody's capable of that. That's why we studied so hard to be able to do that.

When someone goes up to play, I can tell if they're thinking compositionally. That's how I think. I was a composition major at Juilliard, so I think that way.

AAJ: I think I see where you're going with that. Thinking about composition on the spot versus improvisation, improvisation has this connotation that you're just making stuff up.

GB: Right. Like I studied for 70 years just to go and make something up.

AAJ: Right. While composing on the spot requires something of you musically...

GB: Yes, a lot. It's a lot of work.

AAJ: I can see that.

GB: It's really a lot of work. You have to study everything.

AAJ: Right. And being referred to as an improviser takes away from...

GB: It's an insult.

AAJ: I can see that now. I one-hundred-percent agree with that.

GB: I got one! [laughter]

AAJ: No, really. It takes away from what you do artistically when someone insinuates or implies that you're just standing there improvising versus actually seeing you as someone who's creating and composing, like a true artist.

GB: Yes. It took me two years to learn how to start a solo, and another two years to learn how to end a solo. That's just two things. It takes years to learn how to do this.

AAJ: Switching gears, what inspired you to form the NTU Troop?

GB: Probably Max Roach and Charles Mingus. They were making political statements with their music. I grew up in the '60s. It was volatile. They were killing our leaders. It was horrible. At the time, I felt like we don't need another musician. I thought about what else I could do other than play music. I saw that Max, Mingus, and others like Randy Weston were using music as a political tool.

AAJ: And that's what you wanted to do with NTU?

GB: Yes.

AAJ: When did you form (NTU)? In the '70s?

GB: Yes, in the '70s.

AAJ: Your new album called Damage Control is the first in a trilogy that you've called "The Eternal Tenure of Sound." What is the theme of this project?

GB: It was inspired by John Coltrane 's Ballads album. He used Broadway and movie tunes. I'm using tunes from our community. These are tunes that I love and that I sit down and play for my own comfort. I thought, maybe I should do a record like that.

AAJ: Thank you for your time.

GB: Thank you.

Tags

Interview

Gary Bartz

Bridget A. Arnwine

Lydia Liebman Promotions

Sonny Stitt

Eric Dolphy

Rahsaan Roland Kirk

Max Roach

Art Blakey

Miles Davis

John Coltrane

benny golson

Charlie Parker

Charles Mingus

Randy Weston

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.