Home » Jazz Articles » Backstories » Fate Marable’s Mississippi River Conservatory

Fate Marable’s Mississippi River Conservatory

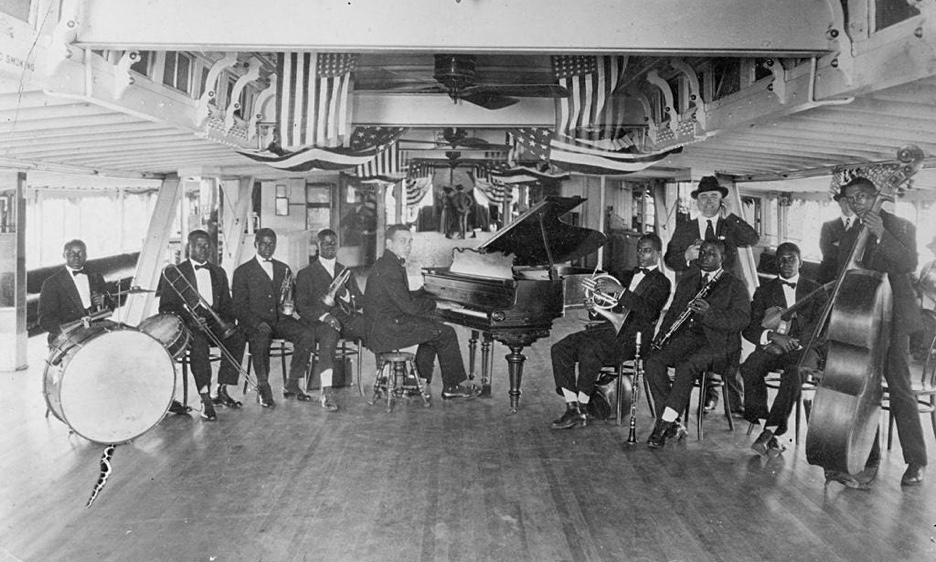

Courtesy Tulane University

When jazz went upstream, it went mainstream.

—William Kenney

Setting Sail

The story of jazz's birth is firmly rooted in the soil of New Orleans, but its first great migration north was on the waters of the Mississippi River. The steamer boats that worked the Big Muddy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were not merely vessels of transportation; they were floating conservatories, incubators, and broadcasting stations for a new American art form. The legacy of these riverboats is deep, shaping the sound, dissemination, and professionalization of early jazz. Bands were hired to entertain passengers on excursion boats that sailed from New Orleans to cities such as St. Louis, Memphis, and St. Paul.The riverboats introduced the New Orleans sound to the entire Mississippi-Ohio river system. Cities like St. Louis, which had its own strong ragtime tradition, and Chicago, which was becoming a major industrial hub, first heard authentic New Orleans jazz played by bands on these steamers. This created an appetite and a market for the music, directly paving the way for the Great Migration of jazz musicians north. As historian William Howland Kenney III argues in Jazz on the River (University of Chicago Press, 2005), the steamboat was "the principal medium through which jazz was transmitted from New Orleans to the rest of the nation."

The Streckfus Steamers

John Streckfus Sr, a son of Bavarian immigrants, entered the steamboat business in 1889. Like many Mississippi and Ohio Riverboat operators of his time, Streckfus focused on freight transportation. However, competing with the expanding railroad network led him to a financially pragmatic shift in his business model around 1901, as Streckfus began transitioning his fleet from freight service to an excursion business.Streckfus' first major investment in the new venture was the JS, a custom-built steamboat with a capacity for 2,000 passengers, featuring a maple dance floor, electric lights, and sleeping berths for the crew and entertainers. The JS was the first steamboat on the Mississippi, built specifically for excursions. This vessel set the standard for all future Streckfus boats, establishing the core formula of combining river transit with onboard entertainment. The success of this venture was so promising that in 1907, Streckfus formally incorporated Streckfus Steamers to raise capital and expand his operations, a move that positioned the company for its most significant growth.

Streckfus acquired the Capitol Diamond fleet, and his steamer, Jo's Dubuque, served the Upper Mississippi and New Orleans, becoming famous as a musical hatchery. At the height of the Jim Crow era, Streckfus gave Charles Mills, an African American composer and pianist, the green light to form an integrated band. In 1907, Mills left the riverboat to pursue musical opportunities in New York. He was succeeded by Fate Marable, a young piano and calliope player, who would go on to become the most famous riverboat jazz bandleader.

Fate Marable

Marable was born in 1890 in Paducah, Kentucky. His mother, a piano teacher, initially prohibited her son from touching the instrument but relented after overhearing him play. She provided his initial musical training, teaching him to read music and laying the foundation for his future career. This early formal training would distinguish Marable throughout his career, as he would later insist that his musicians develop similar literacy.The Marable household was filled with melodies, and Fate Marable eventually had five siblings—brothers Harold and James and sisters Mabel, Juanita, and Neona—all of whom had a hand in music. Little is known about his early years beyond this musical foundation, but by age 17, opportunity called from the river when the Streckfus needed to replace Mills.

Marable began his riverboat career in 1907 aboard the steamer JS. His initial responsibilities extended beyond piano to include mastering the steam calliope, a formidable and unyielding steam organ that presented unique challenges. Steam flowing through brass pipes at 80 pounds of pressure made the keys hot to the touch, requiring Marable to wear gloves during performances. Pitch varied with steam pressure, creating tuning challenges, and the instrument was designed to be heard from shore, creating overwhelming volume for the performer. To manage these conditions, Marable stuffed his ears with cotton and wore raingear in addition to his gloves.

Marable almost immediately became bandleader for a paddle-wheeler, a position he would retain for thirty-three years. Commodore Streckfus maintained strict control over the musical repertoire, supervising tempos with a stopwatch and holding mandatory rehearsals. This environment shaped Marable's own approach to bandleading, emphasizing professionalism and musical rigor.

Marable as Musical Mentor

Marable's most enduring legacy lies in his role as mentor and developer of jazz talent. He spent late nights in New Orleans clubs scouting for promising musicians and playing at jam sessions. It was during one such outing in 1919 at the Cooperative Hall that Marable first heard Louis Armstrong playing with Kid Ory's band. Marable approached the band manager about using Armstrong on nights when Ory didn't need him, thus beginning Armstrong's steady work on the ship Capitol, of the Streckfus Lines.Marable ran what musicians came to call "the school," or training ground, where talented but often informally trained New Orleans musicians developed professional discipline and musical literacy. Drummer Zutty Singleton explained, "There was a saying in New Orleans when some musician would get a job on the riverboats with Fate Marable, they'd say, 'Well, you're going to the conservatory.'" Marable shared the lessons from his mother with his musicians, many of whom played by ear, teaching them to read music and to learn to play from sheet music on sight. As a bandleader, Marable employed strict standards, demanding musical proficiency and rigid discipline while allowing them to develop individuality. He recognized Louis Armstrong's gift for improvisation and allowed him to adlib breaks. Members of Marable's bands were expected to play a wide variety of music, from hot numbers to light classics.

The Riverboat Experience

The riverboat experience provided steady employment, $35 per week with room and board, which was particularly helpful after the closure of Storyville in 1917, when many New Orleans musicians struggled to find work. This financial stability, combined with Marable's leadership, prepared musicians for careers with prominent bandleaders such as Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Jimmie Lunceford, Fats Waller, and Chick Webb.Life aboard the Streckfus steamers was both professionally demanding and physically challenging. The boats operated on a rigorous schedule, with musician Pops Foster describing how "the boat would stop every night in a different town. We started playing about eight. The boat left at nine. We had to play fourteen numbers by 11:30. In addition to evening excursions, the bands played day rides and sometimes performed 'calling concerts' when gangplanks were lowered at 8 PM to attract passengers with flashy material."

The SS Capitol, one of the most lavish vessels in the Streckfus fleet, entertained more than 25,000 tourists in 1920 from Tri Cities docks alone, far more than any competing steamer. These boats "tramped" the Mississippi, traveling from town to town, rarely staying in one place longer than a day or two. In a single season, a boat might visit ports in Wisconsin, Minnesota, Missouri, Illinois, and Iowa. The musical repertoire on these excursions was "arranged dance music of a medium tempo, with apparently little chance for a musician to 'get off'" according to Kenney. This discipline contrasted with the more freewheeling approaches developing in New Orleans and Chicago, but it taught musicians professional adaptability and how to please diverse audiences.

Social and Political Context

The riverboat jazz scene existed within the complex racial dynamics of early 20th-century America. While the music originated in African American traditions, the audience for the excursion was predominantly white. Six days out of seven, the audiences on the boats were white, and the music played by a Black orchestra reassured them that the migration of Blacks to the North would not be threatening. Sundays were typically reserved for African American audiences. This performance context required African American musicians to navigate a delicate social terrain. They entertained white audiences while remaining strictly segregated from them under Jim Crow regulations governing boats. This enforced separation allowed white audiences to maintain familiar racial stereotypes while enjoying the innovative music created by Black musicians. Musicians sometimes viewed Marable's strictness as "slightly darker reflections of the attitudes of his German American employers."The riverboat experience also facilitated crucial musical networking. When boats like the Capitol arrived in ports such as St. Louis, musicians would go ashore for after-hours jam sessions with local players. Louis Armstrong described how he learned from these encounters with St. Louis musicians, much admiring their literacy and musicianship. These interactions helped disseminate jazz innovations along the river system and created professional connections that would later serve musicians when they relocated to northern cities.

Marable's Legacy

Marable's influence on jazz extended beyond the riverboats through the countless musicians he mentored. In 1916, he published his only original composition, "Barrell House Rag," co-written with Clarence Williams. While he recorded only once with his Society Syncopators, his musical legacy lived on through his protégés. Marable continued leading bands on riverboats until 1940, when he retired. He spent his later years playing piano at the Victorian Club in St. Louis. Fate Marable died of pneumonia in St. Louis, Missouri, on January 16, 1947, at age 56.Marable's ability to balance commercial demands with artistic integrity anticipated challenges that jazz musicians would face throughout the century. Perhaps most importantly, by providing training and exposure to generations of jazz innovators, Marable helped ensure the enduring vitality of the New Orleans jazz tradition even as the music evolved.

References

- Chevan, David (1989). "Riverboat Music from St. Louis and the Streckfus Steamboat Line." Black Music Research Journal. 9 (2): 160. doi:10.2307/779421. JSTOR 779421." American Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 3, 2016, pp. 653—79.

- Laurence Bergreen (1997). Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life. New York: Broadway Books.

- Pettinger, Peter (1998). Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 31—32. ISBN 0-300-07193-0.

- Kenney, William Howland. Jazz on the River. University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Fate Marable—Pittsburgh Music History Archived 2016-04-16 at the Wayback Machine.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.