Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » A Tone Parallel to Duke Ellington: The Man In The Music

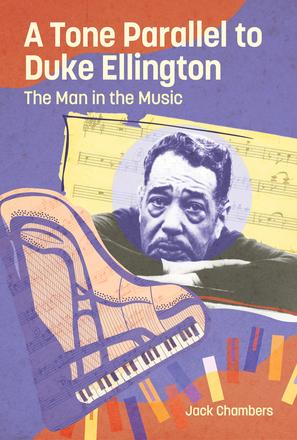

A Tone Parallel to Duke Ellington: The Man In The Music

This, together with Chambers' previous book, 'Such Sweet Thunder,' is some of the best writing about Ellington. It is honest, essential, and tries to penetrate the carapace that Ellington constructed around himself.

A Tone Parallel to Duke Ellington: The Man In The Music

A Tone Parallel to Duke Ellington: The Man In The Music Jack Chambers

259 Pages

ISBN: # 9781496855756

University Press Of Mississippi

2025

There are rare insights into Duke Ellington in this book from Jack Chambers, his second on Duke Ellington. Chambers has also written important books on Miles Davis and Richard Twardzik. He is predisposed to enjoy Ellington's music, can see the flaws in Ellington's personality and throughout the book he describes the diffidence and the traits that limited Ellington's acceptance. The biographies by Terry Teachout, James Lincoln Collier and Thomas Brothers are limited because they all denigrate the achievement of Ellington without really celebrating the richness of the music. Above everything, Chambers loves the music

For any writer on Duke Ellington there is the problem of how to cut through the prodigious amount of work that Ellington produced. In this book, and in his previous book, Sweet Thunder: Duke Ellington's Music In Nine Themes (Canam Books, 2019) each chapter includes a playlist with details of the recordings mentioned in the text, a very useful way of charting a path through the complex discography.

Chambers is keen to point out that the influence of Harlem has been undervalued in comparison with New Orleans. Ellington was part of the Harlem Renaissance. He argues that Harlem was the place "where the New Orleans rhythms and inventiveness were invested with harmonic depth and formal extensions that turned the music into a music that could be admired internationally and, ultimately, globally." Chambers considers and analyzes many of the compositions with Harlem in the title including the major Harlem suite.

The golden age of rail travel coincided with the first half of Ellington's life. There were good reasons for using sleeper trains because racism meant that access to hotels was limited for black musicians in some parts of the country. The many pieces that Ellington wrote around the rhythms of steam trains produced some of his greatest impressionistic pieces from "Happy Go Lucky Local" in the '40s to "Loco Madi" in the '70s. Chambers describes how "Happy Go Lucky Local" was plagiarized by tenor player Jimmy Forrest and turned into "Night Train," creating a great deal of money for Forrest, bitterness from Ellington, and did not elicit much criticism for players who used Forrest's stolen theme.

Ellington constantly denigrated his ability as a pianist. In the section on Ellington as a pianist Chambers describes the few recitals that Ellington played. There was the album made for Capitol Records and recitals at the Whitney Museum, Columbia University and the Museum of Modern Art. The most extraordinary session was "Money Jungle" with Charles Mingus and Max Roach. Chambers points out that Ellington was determined not to be upstaged by the younger musicians. The session was fraught with tensions emanating from Mingus but the unflappable Ellington more than held his own and produced music that displayed an adventurous harmonic sophistication..

One extraordinary omission is comments from Chambers about the album Piano In The Foreground (Columbia Records, 1963) where Ellington played a dissonant version of "Summertime" that is suffused with anger. Aaron Bell, who played bass on the session wryly commented, "That's our winter version."

In a chapter entitled "The Lotus Eaters," Chambers examines the complex relationship between Johnny Hodges and Billy Strayhorn. Chambers examines pieces like "Passion Flower," "Day Dream" and, of course, "Isfahan" from Far East Suite (RCA Records, 1967). The devastating "Blood Count," written as Strayhorn was dying, was the culmination of the relationship. Although very different people, Hodges often seemed taciturn and resentful whereas Strayhorn had a veneer of sophistication. Yet, as Chambers points out, their relationship produced music of unique, sensuous qualities. Chambers gives credit to Ellington; he believes that Ellington orchestrated the alliance between the two men with all the ingenuity that he showed in his musical compositions.

The album Such Sweet Thunder (Columbia Records, 1957) means a great deal to Chambers. He writes: "Such Sweet Thunder of all Ellington's music has been the most abiding. I first heard it in 1957 when it was brand new. It was not the first taste of Ellington's music but it was the one that stayed on my phonograph most frequently." Four of the movements are sonnets, and Chambers points out how deftly Strayhorn and Ellington create the musical sonnets. The four sonnets are as formally strict as Shakespeare's poems. Neither Ellington nor Strayhorn acknowledged the study and hard work necessary to achieve such a satisfying result. Shakespeare's plays are conventionally categorized as comedy, tragedy, history and romance. Strayhorn and Ellington's pieces include representatives from each category.

Chambers' love of Such Sweet Thunder has blinded him to the cultural vandalism perpetrated by producer Phil Schaap on the first CD reissue of Such Sweet Thunder (Columbia Records, 1999). Schaap substituted the a stereo take of the track with Clark Terry as Puck playing "Up and Down, Up And Down (I Will Lead Them Up And Down)." On the original mono release of the album, Terry ingeniously played "Oh what fools these mortals be," a quotation from "A Midsummer Night's Dream," at the end of his solo. It was a brilliant musical comment and an essential part of the suite. Unfortunately, the take that Schaap used did not include the musical quote and, until the suite is remastered, we will be left with an inferior version.

In the chapter "Accidental Suites and Hollywood Scores" Chambers considers Ellington works that have a richness that could be developed further: "Assault on a Queen" and "Anatomy Of A Murder." In each case, Chambers considers the way that the vagaries of film production did not fully exploit Ellington's creativity. The eventual release of the soundtrack of Anatomy Of A Murder (Soundtrack), according to Chambers, revealed themes and melodies that could have been developed into a full-length work. Chambers points out that Ellington was frequently criticized because his longer works were episodic impressions rather than thematically unified movements. In "Paris Blues" the thematic elaborations that recur in various movements, reverberate through the entire length of the film in various guises.

Some writers on Ellington seem to believe that there was little worthwhile Ellington music played after the Fargo performance in 1940. Chambers does celebrate the music of the '60s, particularly "La Plus Belle Africaine" written in 1966. Ellington played it almost nightly until the last concerts in 1974. Chambers argues that the frequency of performance and the fact that Ellington kept it in the book even after the principal soloists had left meant that it was important for Ellington. Strangely, there was only one studio recording which was made when Harry Carney was absent and has never been issued. Chambers comments:" The composition flows more directly from the rhythm trio than perhaps any other orchestral work by Ellington, embodying what Ellington calls 'the blue-blooded Black roots.'"

The saga of the composition of "The River'" reveals a great deal about Ellington's final years. He accepted the commission in 1970 for the American Ballet Theatre with choreography by Alvin Ailey. Eventually, the music existed in several forms. The most accessible version of the 12-movement score that charts the course of a river was written for and played by the Ellington Orchestra. It was also arranged for symphony orchestra. Chambers looks in detail at the various versions of this late work. Ailey became irritated by how Ellington worked and how the creation was fitted in around Ellington's one-nighters with the band. "The River" seemed to Ailey to have a very low priority. Ellington did not even attend the first performance of the ballet at Lincoln Center; he was 700 miles away with the band in Chicago playing before a small audience.

Chambers is honest enough to admit that for Ellington concerts with the band had a high priority even though in later years they could be formulaic. Ellington refused to stop playing the medley of tunes so that newer works could be included. Critic Benny Green wrote, "He regarded his actual concert appearances as something divorced from Ellington the writer of extended works. Once he stepped onto the concert stage, Ellington also stepped into a different persona and saw himself not so much as a composer as an entertainer." Ellington told Green that people would not want to hear the longer works. In the final four years Ellington spent little time in recording studios. He accepted every commission and invitation. Chambers muses that it was as though Ellington sensed his time was limited.

Chambers believes that some criticism had a deleterious effect on Ellington's confidence. During the course of the book, Chambers gradually identifies critics of Ellington. One incident concerned a young man in Paris in 1950 who strode up to Ellington after a performance of "The Liberian Suite" and told him that he came to hear Ellington not this kind of thing. It hurt. Ellington mentioned the incident in his memoir 20 years later. Earlier, critic John Hammond had written that Ellington should confine himself to the three-minute pieces. Hammond was very critical of the Carnegie Hall Concerts that Ellington played in the '40s.

In another snub, the Pulitzer Committee recommended that Ellington should be awarded a life-work prize only to have it withdrawn by the advisory board without any reason being offered. Ellington joked about the incident but such events sapped Ellington's confidence and increased his diffidence. Ellington was extremely articulate but he could talk without revealing too much. Chambers seems to imply that Ellington's casual attitude to his own genius made him his own worst enemy. He did not present himself as a composer. He rarely played his own more serious works. "Such Sweet Thunder" was never performed regularly in its entirety in public. Other suites were neglected too. All the suites were abandoned as soon as the parts were recorded except for occasional individual selections injected into the nightly repertoire. That foible, Chambers believes, had robbed Ellington of the rousing curtain call he had earned.

Even when opportunities arose that might have drawn forth loftier ambitions, Ellington did not exploit them. In 1965 he accepted an invitation to appear as guest soloist with the Boston Pops Orchestra at Tanglewood. Apart from two pieces from his incidental music for performances of "Timon of Athens" at the Stratford Shakespeare festival, the repertoire was decidedly unambitious, concocted not by Ellington or Strayhorn but by a staff arranger supplied by the host.

This, together with Chambers' previous book is some of the best writing about Ellington. It is honest, essential, and tries to penetrate the carapace that Ellington constructed around himself. This is a picture of an Ellington riddled with self-doubt. Chambers has a vast admiration for the music of Ellington and the book is written from that point of view. permeated with the thought that Ellington has still not been given the recognition that he deserves.

Tags

Book Review

duke ellington

Jack Kenny

Miles Davis

Richard Twardzik

Jimmy Forrest

Charles Mingus

Max Roach

Aaron Bell

Johnny Hodges

Billy Strayhorn

Clark Terry

Harry Carney

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.