Most successful people can remember a life altering moment that set their destiny clearly in their view, and for many musicians, this event revolves around a great performance. Coming into contact with live music always leaves a mark on someone with an interest in the art form, but watching a master at work burns a picture into that individual's soul. It inspires a musician to work harder on their craft, raising their technical skills to a higher level. It shows them new approaches, stylistic aesthetics, and musical ideals that they need to research, ingest, and infuse into their musical personality. Overall, these types of events set young people on their path towards becoming a professional musician. Most importantly, they carry that picture of the master throughout their lives, letting it inform every aspect of their professional career.

Drummer and bandleader Bobby Sanabria experienced that revelation as a child while seeing one of the icons of Latin music, Tito Puente. Both a master musician and world class showman, Puente served as a source of inspiration for many young Latino musicians throughout his career. Puente was a model for success—someone who reached a high level of artistic success, massive notoriety around the world, and significant financial rewards. When a young Sanabria saw Puente performing in his New York neighborhood, the important percussionist made a deep and lasting impression. Sanabria carried that inspiration as a guiding light throughout his career, studying all sides of Puente's career and taking those lessons to heart. He would eventually build both a personal and professional relationship that would bring him even closer to Puente's legacy. Over the years, Sanabria has become known as a master musician and important figure in the Latin Jazz community, filled with a deep insight into the music's history. The influence of Puente clearly shines through Sanabria's career, as he now provides the same sort of inspiration to a whole new generation of musicians with an interest in Latin Jazz.

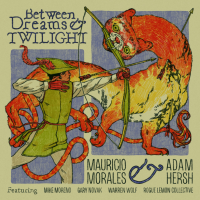

Sanabria recently paid tribute to Puente's inspiration in a recording with The Manhattan School Of Music's Afro-Cuban Jazz Orchestra, Tito Puente Masterworks, Live!!!. The culmination of a semester's work with the group, Sanabria led the young musicians through a repertoire that spanned the entirety of Puente's career. The ensemble learned their lessons well, delivering a blazing display of musicianship that paints a vivid picture of Puente's jazz mastery, compositional prowess, and refined arranging skills. The recording exudes the one thing that Puente held in spades throughout his life—excellence. In Part One of our interview with Sanabria, we discuss Puente's initial impact upon him, the concept behind Tito Puente Masterworks, Live!!!, and some important background information on Puente.

LATIN JAZZ CORNER: I know that Tito was one of your early inspirations to play music, how was Tito influential to you as a young Nuyorican musician?

BOBBY SANABRIA: He was a symbol of forward progress and success. For anybody that came from the hood, whether you grew up in the projects or in the tenements, that was a very, very powerful thing. You saw his face on album covers and heard his incredible musicianship; there was no denying that he represented one thing—excellence. That would inspire anybody.

I got to see him when I was twelve years old in front of the projects that I grew up in. On a summer day, the New York City Parks Department was setting up a stage on the corner of East 1153rd Street and Courtland Avenue, in front of 681 Courtland Avenue, the project that I grew up in. I was looking out the window with my best friend at the time, Marvin Mattei. We were just looking at the crowd getting together, and it was getting big. Who comes out? Ricardo Ray and Bobby Cruz playing with their group. They were hot; they had all those tunes like “Aguzate." They were the hot thing at the time. Doc Cheatham was playing trumpet with them. Then Machito's orchestra comes out! They were doing “Dale Jamón." I'm thinking, “Wow!"

Then Tito Puente starts setting up. I said, “Man, we've got to go down there." Marvin was cracking up; he said, “No, let's stay up here—it's comfortable." I said, “No, we've got to go down there." So we went down and right when we got down there, he started playing “Para Los Rumberos." For a kid that had never heard that before, it was pretty amazing. He raises his left hand up and all of a sudden the saxophone section stands up; it was very majestic. It was very impressive, very inspiring. It's one of those prolific moments that you have that changes your life around.

Of course, I was listening to jazz at that time too. My interest in jazz was growing through watching people like Buddy Rich and Louie Bellson on T.V.—The Tonight Show Orchestra with Johnny Carson. Tito Puente represented the other side of my culture. The thing about Tito Puente is that he represents the perfect blend of jazz culture and Afro-Cuban culture, done with a New York aesthetic. When you hear Tito Puente's music, it resounds New York City. There's no other way that it could sound the way that it does. It's simply a reflection of his upbringing in New York and what the New York ethos is—take no prisoners. It is what it is. It's a music that represents struggle, survival, and triumph. It was very, very impressive.

Over the years at The Manhattan School Of Music, they would give me free reign to put a concert together like most educators at institutions of higher learning. But I would roughly have themes. I'm also very detailed—I would put together extensively detailed liner notes about all the tunes. You're talking about 5,000,000 word essays that I would put into a booklet. So when the people come, they would have a commemorative booklet about the concert. That started happening gradually, more and more. With the Kenya Revisited Live!!!album, that came to its climax. We included pictures of Mario Bauza, extensive descriptions of the tunes—I just went off doing that. I don't mind doing that because I have the knowledge and I want to share it with the public. If you just keep the knowledge to yourself, it doesn't mean anything. Besides the people having a good time, when they get home, they read all that stuff, or when they're waiting for the concert to start, they're reading. They realize, wow, not only is this music entertaining, but it's got a heavy, heavy majestic history.

In terms of this new CD, the person that you have to thank is Debra Kinzler , the head of public relations at The Manhattan School Of Music. She was coming up to me and saying, “You've got to do Tito one day. You've got to do a concert in tribute to Tito." I was saying, “Well, let me get through this Kenya Revisited Live!!!concert . . ." After the Kenya concert, Debbie came to me and said, “Congratulations! Well, now, you've got to do Tito!" So I said, “You're right." Then I took a deep breath and said, “Wow, how am I going to do this?" You start thinking about it.

The music is divided into four different periods. The first period is his early life, which is represented by music like “Picadillo." Then his life during the RCA years, the second period of his life where he really had free reign to experiment as a composer and arranger. He also had the backing of a major record company and on top of that, he had access to the best studio musicians in New York City. He used people like Doc Severinsen on trumpet, Ted Sommer on drums, Joe Grimaldi on baritone, Nick Travis on trumpet, and a bunch of other guys. People like that who are just part and parcel of the New York studio scene. A lot of them played with the NBC orchestra, which eventually became The Tonight Show band. He has access to all of that.

There's a piece from that period, “Mambo Buddha," that is very cinematic—Tito told me that he always wanted to write movie scores. I asked him, “What happened with that?" He said, “I got sidetracked by being a band leader. I love playing and performing too much. If I did movie scores, I'd have to abandon playing." “Mambo Buddha" is a good example of Tito's cinematic writing. It's through composed—there's no improvisation in the whole piece. Although, if you listen to the record that we did, you should really pay attention to what Christian Sands does on the piano to bring out the Asian quality of the song. He does some runs and fills that are amazing. They obviously aren't written in the piece, but using his creativity as a jazz musician, he added that in. It really took the piece to another level.

During the third period in his life, he was basically a dance bandleader. He was always a dance bandleader, but after that period with RCA, that whole concentration on writing jazz oriented pieces like “Elegua Changó," “Cuban Nightmare," kind of ended. That period is represented by pieces like “Ran Kan Kan," which he actually wrote in the early period of his life. There's also “Me Acuerdo De Ti," the piece that he recorded with Celia Cruz.

During the fourth period in his life, he reinvented himself with pieces like “Mambo Adonis," which became “Machito Forever." Basically the last fifteen or twenty years of his life, he wasn't really writing anymore. He was piecemealing that out to other people like Jose Madera and others. He was living off of all the great compositions that he had done in the previous part of his life. You have to understand, he had a grueling, grueling schedule in terms of performance. So if he wrote anything at all, he'd write a sketch and hand it off to somebody else to finish it off. It was very similar to what Duke Ellington used to do with Billy Strayhorn.

The whole emphasis of the album is to showcase him as an incredible composer and arranger. So people can remember that and remember what a great jazz musician he was. That said, there's a lot of heavy drumming on the album.

LJC: I think that a lot of the image that people have of Tito is behind the timbales doing wild solos, but he was a pretty deep composer. His sound really stands out from the mambo big bands.

BS: He had some unique skills. He grew up in New York City in the twenties, which was the beginning of the swing era a time that finally culminated in the late thirties. So his hero was Gene Krupa and he studied all forms of ballroom dancing as well tap dancing. He studied piano as a kid for eight years. Then he studied jazz drumming with a gentleman by the name of Mr. Williams. He was an African-American show drummer—Tito could never remember his first name, he just knew him as Mr. Williams. You put that all together and by the time he's a teenager, he's really a well-formed musician.

By the time that he got into the navy and went to the navy school of music, which in six months gives you four years of conservatory training under the rule of military discipline, you have an incredibly formed musician. By the time that he got out of the navy, he took advantage of the G.I. Bill, and he rolled into the Julliard School Of Music. He obviously had to be accepted first, which was easy enough, but then he completed his studies there in three years. During that three-year period, he was studying the Schillinger system. This was developed by Joseph Schillinger, the Russian musician and theoretician. Basically everything that we do today in jazz arranging has something to do with Joseph Schillinger. He taught George Gershwin. Stan Kenton, Quincy Jones, and many jazz musicians studied the Schillinger system. So many of the things that form jazz arranging comes from Schillinger and Tito studied that. You can hear that in some of the pieces that he wrote. Particularly “Cuban Nightmare." Tito was devotee of Schillinger—he studied Schillinger with a guy named Richard Bender.

Drummer and bandleader Bobby Sanabria experienced that revelation as a child while seeing one of the icons of Latin music, Tito Puente. Both a master musician and world class showman, Puente served as a source of inspiration for many young Latino musicians throughout his career. Puente was a model for success—someone who reached a high level of artistic success, massive notoriety around the world, and significant financial rewards. When a young Sanabria saw Puente performing in his New York neighborhood, the important percussionist made a deep and lasting impression. Sanabria carried that inspiration as a guiding light throughout his career, studying all sides of Puente's career and taking those lessons to heart. He would eventually build both a personal and professional relationship that would bring him even closer to Puente's legacy. Over the years, Sanabria has become known as a master musician and important figure in the Latin Jazz community, filled with a deep insight into the music's history. The influence of Puente clearly shines through Sanabria's career, as he now provides the same sort of inspiration to a whole new generation of musicians with an interest in Latin Jazz.

Sanabria recently paid tribute to Puente's inspiration in a recording with The Manhattan School Of Music's Afro-Cuban Jazz Orchestra, Tito Puente Masterworks, Live!!!. The culmination of a semester's work with the group, Sanabria led the young musicians through a repertoire that spanned the entirety of Puente's career. The ensemble learned their lessons well, delivering a blazing display of musicianship that paints a vivid picture of Puente's jazz mastery, compositional prowess, and refined arranging skills. The recording exudes the one thing that Puente held in spades throughout his life—excellence. In Part One of our interview with Sanabria, we discuss Puente's initial impact upon him, the concept behind Tito Puente Masterworks, Live!!!, and some important background information on Puente.

LATIN JAZZ CORNER: I know that Tito was one of your early inspirations to play music, how was Tito influential to you as a young Nuyorican musician?

BOBBY SANABRIA: He was a symbol of forward progress and success. For anybody that came from the hood, whether you grew up in the projects or in the tenements, that was a very, very powerful thing. You saw his face on album covers and heard his incredible musicianship; there was no denying that he represented one thing—excellence. That would inspire anybody.

I got to see him when I was twelve years old in front of the projects that I grew up in. On a summer day, the New York City Parks Department was setting up a stage on the corner of East 1153rd Street and Courtland Avenue, in front of 681 Courtland Avenue, the project that I grew up in. I was looking out the window with my best friend at the time, Marvin Mattei. We were just looking at the crowd getting together, and it was getting big. Who comes out? Ricardo Ray and Bobby Cruz playing with their group. They were hot; they had all those tunes like “Aguzate." They were the hot thing at the time. Doc Cheatham was playing trumpet with them. Then Machito's orchestra comes out! They were doing “Dale Jamón." I'm thinking, “Wow!"

Then Tito Puente starts setting up. I said, “Man, we've got to go down there." Marvin was cracking up; he said, “No, let's stay up here—it's comfortable." I said, “No, we've got to go down there." So we went down and right when we got down there, he started playing “Para Los Rumberos." For a kid that had never heard that before, it was pretty amazing. He raises his left hand up and all of a sudden the saxophone section stands up; it was very majestic. It was very impressive, very inspiring. It's one of those prolific moments that you have that changes your life around.

Of course, I was listening to jazz at that time too. My interest in jazz was growing through watching people like Buddy Rich and Louie Bellson on T.V.—The Tonight Show Orchestra with Johnny Carson. Tito Puente represented the other side of my culture. The thing about Tito Puente is that he represents the perfect blend of jazz culture and Afro-Cuban culture, done with a New York aesthetic. When you hear Tito Puente's music, it resounds New York City. There's no other way that it could sound the way that it does. It's simply a reflection of his upbringing in New York and what the New York ethos is—take no prisoners. It is what it is. It's a music that represents struggle, survival, and triumph. It was very, very impressive.

Over the years at The Manhattan School Of Music, they would give me free reign to put a concert together like most educators at institutions of higher learning. But I would roughly have themes. I'm also very detailed—I would put together extensively detailed liner notes about all the tunes. You're talking about 5,000,000 word essays that I would put into a booklet. So when the people come, they would have a commemorative booklet about the concert. That started happening gradually, more and more. With the Kenya Revisited Live!!!album, that came to its climax. We included pictures of Mario Bauza, extensive descriptions of the tunes—I just went off doing that. I don't mind doing that because I have the knowledge and I want to share it with the public. If you just keep the knowledge to yourself, it doesn't mean anything. Besides the people having a good time, when they get home, they read all that stuff, or when they're waiting for the concert to start, they're reading. They realize, wow, not only is this music entertaining, but it's got a heavy, heavy majestic history.

In terms of this new CD, the person that you have to thank is Debra Kinzler , the head of public relations at The Manhattan School Of Music. She was coming up to me and saying, “You've got to do Tito one day. You've got to do a concert in tribute to Tito." I was saying, “Well, let me get through this Kenya Revisited Live!!!concert . . ." After the Kenya concert, Debbie came to me and said, “Congratulations! Well, now, you've got to do Tito!" So I said, “You're right." Then I took a deep breath and said, “Wow, how am I going to do this?" You start thinking about it.

The music is divided into four different periods. The first period is his early life, which is represented by music like “Picadillo." Then his life during the RCA years, the second period of his life where he really had free reign to experiment as a composer and arranger. He also had the backing of a major record company and on top of that, he had access to the best studio musicians in New York City. He used people like Doc Severinsen on trumpet, Ted Sommer on drums, Joe Grimaldi on baritone, Nick Travis on trumpet, and a bunch of other guys. People like that who are just part and parcel of the New York studio scene. A lot of them played with the NBC orchestra, which eventually became The Tonight Show band. He has access to all of that.

There's a piece from that period, “Mambo Buddha," that is very cinematic—Tito told me that he always wanted to write movie scores. I asked him, “What happened with that?" He said, “I got sidetracked by being a band leader. I love playing and performing too much. If I did movie scores, I'd have to abandon playing." “Mambo Buddha" is a good example of Tito's cinematic writing. It's through composed—there's no improvisation in the whole piece. Although, if you listen to the record that we did, you should really pay attention to what Christian Sands does on the piano to bring out the Asian quality of the song. He does some runs and fills that are amazing. They obviously aren't written in the piece, but using his creativity as a jazz musician, he added that in. It really took the piece to another level.

During the third period in his life, he was basically a dance bandleader. He was always a dance bandleader, but after that period with RCA, that whole concentration on writing jazz oriented pieces like “Elegua Changó," “Cuban Nightmare," kind of ended. That period is represented by pieces like “Ran Kan Kan," which he actually wrote in the early period of his life. There's also “Me Acuerdo De Ti," the piece that he recorded with Celia Cruz.

During the fourth period in his life, he reinvented himself with pieces like “Mambo Adonis," which became “Machito Forever." Basically the last fifteen or twenty years of his life, he wasn't really writing anymore. He was piecemealing that out to other people like Jose Madera and others. He was living off of all the great compositions that he had done in the previous part of his life. You have to understand, he had a grueling, grueling schedule in terms of performance. So if he wrote anything at all, he'd write a sketch and hand it off to somebody else to finish it off. It was very similar to what Duke Ellington used to do with Billy Strayhorn.

The whole emphasis of the album is to showcase him as an incredible composer and arranger. So people can remember that and remember what a great jazz musician he was. That said, there's a lot of heavy drumming on the album.

LJC: I think that a lot of the image that people have of Tito is behind the timbales doing wild solos, but he was a pretty deep composer. His sound really stands out from the mambo big bands.

BS: He had some unique skills. He grew up in New York City in the twenties, which was the beginning of the swing era a time that finally culminated in the late thirties. So his hero was Gene Krupa and he studied all forms of ballroom dancing as well tap dancing. He studied piano as a kid for eight years. Then he studied jazz drumming with a gentleman by the name of Mr. Williams. He was an African-American show drummer—Tito could never remember his first name, he just knew him as Mr. Williams. You put that all together and by the time he's a teenager, he's really a well-formed musician.

By the time that he got into the navy and went to the navy school of music, which in six months gives you four years of conservatory training under the rule of military discipline, you have an incredibly formed musician. By the time that he got out of the navy, he took advantage of the G.I. Bill, and he rolled into the Julliard School Of Music. He obviously had to be accepted first, which was easy enough, but then he completed his studies there in three years. During that three-year period, he was studying the Schillinger system. This was developed by Joseph Schillinger, the Russian musician and theoretician. Basically everything that we do today in jazz arranging has something to do with Joseph Schillinger. He taught George Gershwin. Stan Kenton, Quincy Jones, and many jazz musicians studied the Schillinger system. So many of the things that form jazz arranging comes from Schillinger and Tito studied that. You can hear that in some of the pieces that he wrote. Particularly “Cuban Nightmare." Tito was devotee of Schillinger—he studied Schillinger with a guy named Richard Bender.