Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Cooper-Moore: Catharsis and Creation in Community Spirit

Cooper-Moore: Catharsis and Creation in Community Spirit

The music has always been a survival tool. The music has given release and relief from the reality. I hope the music that I help create does the same. For me it’s not about going to Saturn or finding God, but just making being on the Earth easier.

—Cooper-Moore

This is what Cooper-Moore does; he turns things around when you least expect it. Or perhaps, it would be better to say he exposes the way of thinking that is so common among music writers, including myself, the quest for the greatest records. This way of thinking is the consumer's point of view and belongs in the world of reviews and ratings, but the point is that music is also communication and in terms of records who knows what the individual listener needs and when? There are times when Cooper-Moore's deeply felt lyrical readings of William Parker's compositions on Stan's Hat Flapping in the Wind will bring most joy, but his solo piano tour de force of musical styles on Deep in the Neighborhood of History and Influence will also take the listener on an adventurous journey. Other times his forceful interplay with David S. Ware might be needed or the trio language of his group Triptych Myth.

Music provides various energies and emotions to different listeners and words are only poor servants to describe what's going on. Describing something as "lyrical" or "forceful" doesn't say much. Perhaps, the listener has to find a starting point free from the hierarchical opinions of others and in that sense any record could be a good beginning.

One of Cooper-Moore's own beginnings came from The Hucklebuck, as he recalls:

"The Hucklebuck was an R&B, Blues recording that came out in 1949. It's the first commercial music that I have memory of. There were children's songs and church hymns that I have a sense of from when I was three years old, but The Hucklebuck was a 78 rpm recording of our parents that was played on an old hand cranked RCA Victrola that was played over and over. And everytime it was played everybody would dance. And hearing it made all of us in the room happy."

"Then there were radio dramas with musical underscores. Those scores carried a lot of the emotion of the story. Our daily lives had no musical accompaniments. But African American speech, as I remember it as a child, was rich and full of tones and inflections that would take words to the place of song. This is also what I heard in church, the preacher would begin speaking and over time the speaking turned into song. I remember my mother saying something that upset me. An older brother later said to me, "Oh no, she didn't mean it that ways." That's when I learned, around 5 or 6, that "how" words were spoken held as much meaning as the words."

To this day, the connection between music and vocal is still crucial to Cooper-Moore. When I asked him whether he heard music primarily as melodies or rhythms, he said: "I don't hear music as one or the other. Music, when I listen to music, usually sounds vocal, conversational. If it doesn't sound that way, I lose interest."

Cooper-Moore's interest in the vocal aspect of music has also come across in the reading of the poem "The Agony of These Feelings Felt" from the concert recording Deep in the Neighborhood of History and Influence. About the relation between words and music, he says: "Adding words, for me, gives an up front clear idea of what I am saying. When I express words in a performance, they for me are song. I feel the music that most resonates with me, when heard, sounds like some kind of spoken language."

The conversational aspect also underlines music as something you do in a community and a thing that brings joy. This communal experience of music also goes back to Cooper Moore's time in the school bands:

"In grammar school and high school I played in the school bands. Playing in those bands changed me. A band is a community that makes music together. It's a powerful thing. You have to do your job and at the same time pay attention to what the other players are doing. School bands are organized, structured, and disciplined. As a member you learn to be responsible and take care of your part."

Cooper-Moore's way into music came through the experience of listening and playing in a community. When it comes to the romantic concept of the artist singling himself out as something special outside the community, he is skeptical. Reflecting on the word, he says:

"'Special' as applied to me being special is something that I have always shied away from. In the southern African American communities that I knew, the term was very much associated with how white people thought of themselves. The white supremacist attitude that gave them rights over black, brown, red and yellow peoples. With us the only time that someone was termed special was when the community deemed them special. If a person felt the call of God to preach the Gospel, he or she would go before the church congregation and announce, "I've been called." The person would then go through a probation period, a test, and be observed in the community by its member young and old whether they were fulfilling the duties of one who has been called."

"I did not feel that I had special talents until I had been told so by musicians whom I respected, or musicians whom I respected asking me to play music with them. Even then I was hesitant to believe it. And I think it is best not to believe such. I do believe that sometimes special things happen when I am in creative mode."

"But cumulatively, special when creating will change who you are when you are not creating. Those changes can be good or bad depending on how we react to them and whether or not we have love and security and safety in our lives."

When it comes to the solo concert situation heard on Deep in the Neighborhood of History and Influence, Cooper-Moore is also demystifying the role of the detached artist singled out as being special. Instead of using the concept of high art as a way of separating himself from the audience, he reaches out to the people with a varied program and takes the situation down to earth. Speaking of the difference between high art and folk art, he says:

"Where I'm from, high art = white people or those with the money and the power. Folk art = those people of color or those with little money or power who do not get to choose. To me it is those in power that use that power to devalue those not in power and to keep that the status quo. The history of the music that I love and admire had Duke Ellington, who talked to the people and often gave a narrative of what the music was about. Cannonball Adderley did the same. Dizzy was a funny cat, as was Satchmo. And Monk was hilarious in his playing when he wanted to be. Blues is about the lives of real people like ourselves and is earthy by its nature. The programing of bands of my youth was always varied: something up tempo, a ballad, a blues, a standard, a shuffle, some latin or calypso. This was music that worked for audiences. They paid to hear it. There are musicians today who live off of grants. The composer, Virgil Thomson, made the comment that where an artist gets his money to live determines what the art will be.

In his own upbringing, he didn't think about art as a concept for an individual talent, but there was a lot of creativity in the family:

"When I was growing up, there was no sense of "art or artist" in our lives. Art was something white people did, Rembrandt, Picasso, Monet, those cats. Even studying piano was about gaining skills to a job, playing in church or for school functions. When I turned 12 years old and found an interest in jazz and those people who played it, I didn't understand them as being what might be defined as jazz artists."

"Nevertheless, yes, my people were creative people. My older brother, MacArthur, was a builder of things —Radio controlled airplanes, ice boats, kites, electronic devices. Most often he built from his mind, his imagination, no plans or guides on paper. My mother sewed much of what we wore as children and nearly all that she wore, and they were most beautiful. Our younger sister, Gertrude, was painting from the time she was 6 years old and at 70 paints and is considered an artist in the community where she lives. She exhibits her work. My older sister, Vivian, studied piano until her teens and would hold me in her lap as she practiced her lessons. She married a pianist, Emery Austin Smith, who taught and mentored me as a musician and still performs those duties in my life until this day. My sister no longer plays piano but later in life became a quilt maker and exhibits her work in the community where she lives."

Cooper-Moore's own outlet for creativity ended up being music and through his early years, he listened to all kinds of music:

"Early on the music that I mostly heard was blues, R&B, Bluegrass, Country and whatever was on pop radio and TV. Sunday mornings it was church hymns, gospels and spirituals. But when I turned 12, jazz became the music that I sort out as my listening preference. Mingus, Monk, Ornette Coleman, Duke, Ahmad Jamal, Art Blakey, Oscar Peterson, Jimmy Smith, Count Basie, Bird. Then I became a Miles Davis fan, which is how I came upon John Coltrane. Because of the Movement against the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement I began hearing and buying folk music, Dylan, Joan Baez, etc. When I was 17 I met a man, Huntington Harris, who became a mentor, patron and friend. He owned a radio station in the town and on Sunday afternoons had a show and played classical works. Because of him I formed an interest in that music."

When it comes to inspiration, Cooper-Moore has been influenced not only by music, but also by the teachers he has met through his journey: "I have had many teachers: parents and siblings, friends and relatives, formal teachers and those from the street, poets and painters, gym rats, dancers and actors of stage and screen, those with lots and those with none at all; equal to one another." One person who was very important was his piano teacher, Mrs. Gray:

"My first piano teacher, Mrs. Gray was the most important teacher that I've had. There have been many. She was also my first grade teacher with 47 students. All who went through her class remember her with honor and respect. She was on par with any military general. So when I began lessons on piano with her, I saw a totally different person. Here was a person that was relaxed, felt good about self, was free and not strict at all. I got to know her as a musician, another comrade. There were many to come but none that come anywhere close to Mildred Gray. She put me on the path that I still travel. Emery Austin Smith has helped keep me on the path. David S. Ware and his memory fuels the journey."

Cooper-Moore began piano studies in October 1954. It was his first instrument and has a complex history. His history with the piano has also developed through the years:

"The history of piano playing is long. That history is also a challenge to anyone who sits down at one to perform for a knowing audience. To me the piano is a tool for reaching inside oneself to release feelings that will in some way resonate with an audience. My initial relationship with piano was probably selfish. I was looking to how much it was fulfilling for me, selfish. Even when there were observers present, I'd be in selfish mode. My thinking now goes beyond being observed. It is now more like a sharing mode. I say to the piano, "OK, Piano, let's do some music for these people." I feel I've made some peace with the instrument and the relationship is one of a partnership."

While Cooper-Moore has made peace with the piano, it is still an impractical instrument for a musician:

"Pianos are heavy. We usually don't carry them around to where we are going to play. When we do have a gig someplace, the piano is often an unknown. Hopefully it's in good repair and in tune. The majority of instrumentalists have and carry their own instruments and do not have my concerns of becoming acquainted with an unknown entity. Possibly, this might have something to do with why I feel so complete when I play the instruments that I have built."

Even though he builds his own instruments and has a long history with the piano, Cooper-Moore doesn't attach himself to a particular instrument: "I am a Musician. I don't identify with any instrument, nor do I have any attachments to any of them. If one goes missing I build another one."

The idea of making his own instruments first came into being when he saw a harp that he wanted:

"I saw a man playing a harp from South America and wanted to have one. The Harp Store wanted $5000 for one like it. That was too expensive so the one that came to my imagination, and was created, cost $8. A bundle of wood found on the street fed my imagination and became the Ashimba. I hope what I have demonstrated is that it doesn't make any difference what the instrument is. It is about the person playing it. The instrument is a tool used to transmit information (music), to which people react. That data is coming from or through us. Instruments come to me in visions, imaginings that grow over time in my mind until my hands move to materialize them. I don't know what they are going to be or how they are to sound or be played. I tell people that 'the software comes with the hardware.'"

At the core of Cooper-Moore's musicianship lies the approach of improvisation and it is something he still sees developing:

"Improvisation in the African American tradition is a survival skill. It starts early. Improvisation in music is something that for me is in a state of becoming. The how and the why are continually changing." Speaking of difference between improvisation and composition, he says: "To me, improvisation and composition are two tools humans all over the world use to transmit feelings and emotions that hopefully resonate with other humans. As tools of music, we use them to connect with others and to help others connect with one another."

When it comes to his own musical language, Cooper-Moore is reluctant about describing it: "Others have to identify any musical language which I might have. But I feel the Blues when I play."

The idea of catharsis is closely connected to the blues and it also plays an important role in Cooper-Moore's music:

"As someone raised on the blues and growing up in the Black Church in America, Catharsis is the point. TheBullShit Reality of some of those in power in my country today has been the reality of African Americans here for centuries. The music has always been a survival tool. The music has given release and relief from the reality. I hope the music that I help create does the same. For me it's not about going to Saturn or finding God, but just making being on the Earth easier."

In 2017, Cooper-Moore was acknowledged for his contribution to music and it gave him the opportunity to release a lot of music presented on four albums that are available through his website:

"In 2017, ARTS FOR ART gave me a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 22nd Vision Festival in New York City. This was a week long opportunity to sell product and I had none. Along with the four CDs I published a book of compositions which were sold. Looking Back 1 and Looking Back 2 are from "COOPER-MOORE: A Retrospective 1990-2010," a web page that was up for two weeks. The works are from recordings, concerts, dramas, modern dance projects, commissions, experiments over a twenty year period while living in NYC from 1990-2010 and gives a better representation of what I was doing and how I was thinking during that time. Visitors to the online page were allowed to download all of the music free of charge. After two weeks I took the site down."

One of the albums is Deep in the Neighborhood of History and Influence and it's a re-release of a concert recording first released on Hopscotch Records in 2001. When asked about the circumstances of the recording, Cooper-Moore says:

"1999 I received a grant of $5000 and spent half on a Roland VS-1680 hard disk recorder. The concert recording was the first time that I used it. I took a line out from the house PA system. I had a lot of anxiety that the inputs might distort. That was my main concern other than the owner of the venue was freaking out. He believed that I was abusing his brand new Yamaha Grand. I announced that the pianist the following night was going to be playing even harder than I. That was Vijay Iyer. The owner cancelled Vijay's concert. Vijay does not play harder than I play."

Deep in the Neighborhood of History and Influence includes an extended essay on the music and the two retrospective collections, Looking Back #1 and Looking Back #2 both include track notes, but there is little information about Solo Piano #2. About the album, he explains:

"The Spring of 2012 I toured Europe with Marc Ribot's band, REALLY THE BLUES. I played organ. Marc pays well so when I returned to New York City I spent a chunk of the money on studio time to put down some ideas and concepts that I felt I wanted to develop, clusters with melodies on top, single line improvs with either hand, trying to make the piano have a voice, not playing changes and patterns, always thinking the blues."

One thing that is noticeable about the album is the length of the pieces, many of them are short. When asked about the difference between the long form and short form and the advantage of the latter, he says:

"I have no thoughts about short term advantages. I haven't heard other player thinking that ways, at least in the jazz world. I have some memory of classical composers creating short pieces. They were not in my thinking then. I was just trying to record ideas and concepts that I had not until then put into a collection. There was no thinking that these works would be released."

Aside from the four albums released through his website, another Cooper-Moore-related release has recently come to light. It's the album Finding Fire that was released on Birdwatcher Records in 2018. It's a previously lost recording he did with the trio Triptych Myth and the saxophonist Cale Brandley:

"After the 9/11 destruction of the World Trade Center building in Lower Manhattan, Patricia Parker of the Vision Festival decided that the community needed to come together to celebrate life. New York City had the smell of smoke and of death hanging over it. She organized a concert with many participating performers and asked me to lead a quartet with Matt Mottel on keyboard, Byrne Klay on bass, and Cale Brandley on tenor sax. They were all around 18 or 19 years old. I had never met them before we got on stage to play. I played drums. Cale was pretty much well along the path as a player. I suggested to him that he should record."

They ended up recording together and even though Triptych Myth plays a significant role on the record, Cooper-Moore stresses that it was not a Triptych Myth record, but Cale Brandley's record:

This was Cale's session. Triptych Myth was just the rhythm section. Not long after the session, Cale spoke or wrote to me about how unhappy he was with the session and how the rhythm section had performed. I did not hear from him since that recording date when he wrote several months ago and apologized for his words, that he had been wrong and let me know that he had released the music.

Hearing the music now, it's hard to explain why it took so long time to release it, but the good news is that it's here and there are also other projects in the pipeline:

"From mid July 2018 to mid-December 2018, Stephen Gauci on tenor and I on piano did a duo at Happy Lucky #1, an art gallery in Brooklyn NY. We went into a studio and recorded the duo. It should be available soon. I will have a solo piano recording coming out this year and maybe one with my instruments. For the past couple of years, I've been setting the words of librettist, Jacqueline Fabius. This project, A MOORISH NIGHT, is a big one."

Cooper-Moore still lives and works in New York and when asked about the music scene, he points out that the concept of scenes often results in polarization:

"I am 72 years old and rarely go out to performances unless I'm playing. There are a number of scenes in New York. A scene is generally centered around an individual or individuals that make it happen. They have a certain philosophy or play a certain way. Sometimes they form an organization and the scene becomes more organized and even funded. Sometimes a scene is centered around a place, like a loft or a bar. But wherever there are scenes there arises the sense of us and them, a sense of what we do is better than what they do. Jealousies are rampant. I don't think that anything is any different from what it has always been, except the characters have changed. New people come to town. They want gigs. There are a finite number of opportunities for them. Some of those who were here first resent the new comers. There are turf wars. Some win. Some lose."

Life as a working musician can be hard, but in spite of the challenges, Cooper-Moore sums up his journey so far on a positive note: "Staying on the path is not easy but the dreams I had as a child have all come true. I am happy."

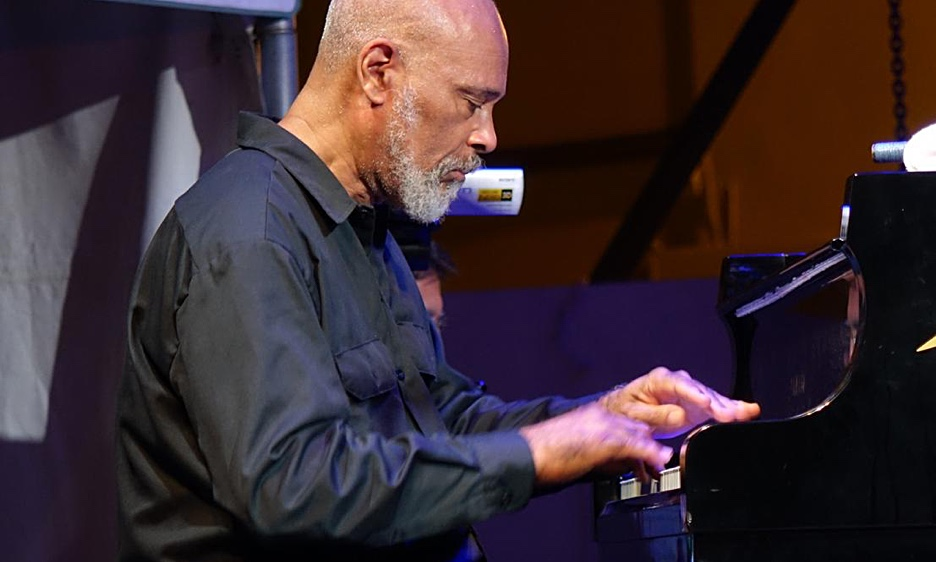

Photo Credit: Frank Rubolino

Tags

Interviews

Jakob Baekgaard

United States

New York

New York City

Cooper-Moore

William Parker

David S. Ware

duke ellington

Cannonball Adderley

Ornette Coleman

Ahmad Jamal

Art Blakey

oscar peterson

Jimmy Smith

Count Basie

Miles Davis

Emery Austin Smith

Vijay Iyer

Marc Ribot

Patricia Parker

Matt Mottel

Byrne Klay

Stephen Gauci

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.