Home » Jazz Articles » History of Jazz » The Creative Musicians Improvisers Forum: New Haven's AACM

The Creative Musicians Improvisers Forum: New Haven's AACM

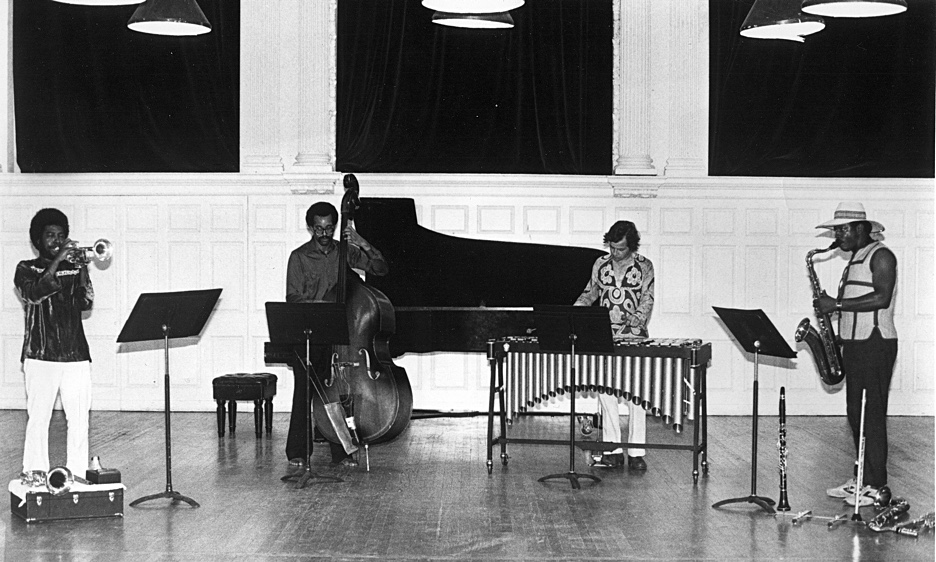

As in Chicago, St. Louis, Los Angeles and New York, in New Haven improvised music informed by the avant-garde or free jazz aesthetic was at the margins of a larger jazz scene that was itself becoming commercially marginal. At the same time, though, it was a music undergoing a creative ferment that was specifically tied to its location. South Central Connecticut in the 1970s was home not only to Yale, whose students included Anthony Davis, Jane Ira Bloom, George Lewis and others who would contribute significantly to the development of new improvised music, but also to Wesleyan University in nearby Middletown, which since the early 1960s had been developing an ethnomusicological program—a program that would exert a notable influence on creative musicians interested in exploring the traditions of non-Western musics. It was also the place where a critical mass of forward-thinking musicians happened to emerge. Some were local professionals, some were professionals from elsewhere, some were students, but all shared an interest in new developments in improvised and composed music and in the supporting social infrastructure that was beginning to be built by creative musicians around the country. Among them were the five founders of CMIF: trumpeter Leo Smith (before he adopted the name "Wadada"); vibraphonist Bobby Naughton, saxophonist Dwight Andrews, double bassist and multi-instrumentalist Wes Brown; and percussionist Gerry Hemingway.

Smith was a major catalyst not only for forming CMIF specifically, but more generally for bringing together and inspiring like-minded artists in the New Haven area. Of the collective's principal figures, he had probably taken the most circuitous route to New Haven. Born in Mississippi, he went to Chicago in 1967 after serving in Army bands that toured Europe and the United States. His time in Chicago would prove to be pivotal not only for his personal development as an artist, but for the New Haven scene he would eventually help to galvanize. For, shortly after his move to Chicago, he became a member of AACM. His experience in that collective was critical for demonstrating how artists could form an effective, mutually supportive community to sustain themselves and their artistry in challenging circumstances. One lesson he took away from Chicago was that the individual artist, if he or she were to thrive precisely as an artist, must necessarily be involved in the collective life of the larger community.

While in Chicago, Smith worked closely with Anthony Braxton and Leroy Jenkins, with whom he formed the Creative Construction Company. In 1969, he moved to Paris with Braxton and Jenkins and stayed for a year, giving performances and making recordings with them and with other musicians who happened to find themselves there, the Art Ensemble of Chicago among them. After returning to America he relocated to the New Haven area, in 1972.

Not long after he settled in Connecticut, Smith began to work with some of the younger musicians he met there and who he felt shared his attitudes toward music. He formed what was to be the first of his long-term groups, New Dalta Ahkri (sometimes called New Delta Ahkri), with pianist Davis, bassist Brown, and drummer Paul Maddox (later known as Pheeroan AkLaff). The group would go on to make several recordings that Smith put out on his own Kabell label—happily, all four LPs, along with some previously unreleased recordings, were reissued by John Zorn's Tzadik label in 2004—and to feature a flexible membership that would include saxophonist Oliver Lake, Naughton, and others. It was during this same period that Smith also got involved with post-secondary education, teaching improvisation during the 1975-1976 academic year at the University of New Haven and studying ethnomusicology, particularly the musics of West Africa, Indonesia and aboriginal North America, at Wesleyan.

Naughton started out closer to New Haven. Originally from Boston, he played piano as a child, and prior to an Army stint in the 1960s, played keyboard in rock bands. In 1966 he switched to vibes and shifted his attention to free jazz, which he discovered through his manager's record collection; within a few years he was playing with clarinetist Perry Robinson and studying George Russell's theory of Lydian tonal organization. By the early 1970s he, too, was in New Haven, where he formed a friendship with Smith and played in New Dalta Ahkri.

Originally from Detroit, Andrews studied classical clarinet at the University of Michigan, where he earned a master's degree in woodwind performance. It was as part of the school's marching band—playing in it was a requirement under the terms of his scholarship—that he took up saxophone. After Michigan Andrews came to New Haven to begin studies at the Yale Divinity School, where he obtained a Master of Divinity degree in 1977. While at Yale he led a kind of double life, studying theology on the one hand, and continuing to play music on the other. He formed the band Déjà Vu with fellow Detroit native akLaff, vibraphonist Jay Hoggard, keyboardist Nat Adderley, Jr. and vocalist Phillipa Overstreet; akLaff remembered it as a "hip" R&B cover band that, at one Yale gig, found itself on the same bill as a trio led by Leo Smith.

Brown, a multi-instrumentalist playing double bass, percussion and flute had, like Smith, studied ethnomusicology at Wesleyan. In the early 1970s, he was playing in groups with Anthony Davis and trombonist George Lewis, who was then at Yale working toward a degree in philosophy. It was through an ad that Hemingway placed in Rolling Stone magazine in 1972 that Brown and he met; the drummer was seeking a bassist and pianist for a trio inspired by the example of Chick Corea's album Now He Sings, Now He Sobs. New Haven native Hemingway had been a professional drummer playing jazz and bebop since dropping out of school at age 17; now, through Brown, he met Davis and began playing in Davis' group Advent. Shortly after, Hemingway went to Boston to the Berklee College of Music but soon dropped out and returned to New Haven, where through Davis he met Smith. It was also during this period that he audited classes at Wesleyan and took private lessons in West African drumming from Wesleyan adjunct professor Abraham Adzenyah, and studied South Indian drumming with mridangamist Ramnad V. Rhagavan, a Wesleyan artist-in-residence.

By the mid-1970s, then, an informal network of creative musicians was in place in New Haven. All that was needed to solidify it was a stimulus. One such stimulus came by way of a 1975 concert dedicated to the music of Duke Ellington. The performance had gone well and helped convince some of the participants of the desirability of perpetuating its success in a more permanent form. And in fact the ensemble that had been put together for the occasion, which called itself the Creative Improvisors Orchestra, would go on to become CMIF's associated performance group.

More generally, the idea of starting an artists' organization seems to have been in the air, given the difficulties facing New Haven's creative musicians in finding work and in disseminating their music. In an interview published in the September, 2014 number of The New York City Jazz Record, Naughton recalled that he and some others had talked about doing something to promote working opportunities and to get their music out to a broader audience. That something turned out to be CMIF.

The Creative Musicians Improvisors Forum was formally organized in March, 1977 as a non-profit educational entity. The new organization quite naturally took the AACM as its model—Smith, describing CMIF in a 2014 oral history interview for the California Institute for the Arts, likened it to having sprung from a seed given off by the AACM that had fallen to the ground in New Haven. Double bassist and Connecticut native Mario Pavone, an early member, recalled in a 2002 interview that Smith was CMIF's "guiding force" and that the New Haven organization's principles were "loosely based" on those of the Chicago collective. With a racially mixed membership that numbered up to twenty at a time, CMIF could fairly claim to be representative of the diverse local creative music community. The organization attracted federal funding as well as Connecticut state money; private support came from local businesses. On the program side, CMIF formed alliances with other arts organizations, the Hartford Jazz Society among them.

Once established, CMIF set out an ambitious agenda that found expression in Smith's "CMIF: Toward a World Music," a manifesto which also served as the liner note to the group's LP The Sky Cries the Blues. In the manifesto Smith articulated a program of self-reliance and collective action intended to support members' creative and career development. Clearly inspired by the example of the AACM, the group was envisioned as a body that would "sponsor, encourage and promote the production and performance" of its members' musical activities by staging concerts, issuing recordings and commissioning new work. As CMIF's performance unit, the Creative Improvisors Orchestra was the collective's vehicle for getting its members' work played. The group also established a record label and publishing company. The Sky Cries the Blues, recorded in Southbury, Connecticut in 1981 and issued in 1982 with the catalogue number CMIF Records 1, appears to have been the label's sole release.

In addition to promoting its members' creative activities, CMIF was also projected to have an educational function. Teaching, whether in terms of formal lessons or simply the transmission of the key concepts of a tradition, was an important part of Smith's musical practice even if his early involvement with teaching at the university level was short-lived and ultimately disappointing. (As Smith recalled in his 2014 oral history interview, his improvisation class at the University of New Haven attracted a large number of students but the music department refused him a permanent position because he lacked a Ph.D.) More successful was an eight-week course he taught not long before CMIF was organized. Called "The Art of the Improviser," it took place outside of a formal academic setting and was based on his understanding of the blues and the role of the blues in improvisation. During its lifetime CMIF did have an educational component that consisted of outreach visits to schools, churches and community centers throughout Connecticut. As percussionist Ralph Yohuru Williams described it in a December, 1982 video of a Creative Improvisors Orchestra open rehearsal made for Bridgeport's WUBC-TV, CMIF even visited nursery schools in order to show children that musicians could play in an ensemble that wasn't a symphony orchestra.

Beyond its basic educational program, Smith also called for CMIF to establish a conservatory as well as what he described as an "aesthetic research center." The latter was of a piece with the group's stated interest in developing a creative music drawing on global musical traditions which, Smith's manifesto asserted, meant acquiring knowledge not only of specific musical techniques but of the "social, philosophical and religious systems" in which they were embedded. CMIF, in effect, saw itself as a kind of ethnomusicological program that would foster a more than superficial fusion of the world's musics; rather, it would look at the sources of those musics, something Smith in another context referred to as the spirituality within them. What the collective aimed for was, as Smith emphatically put it, a "CREATIVE WORLD MUSIC."

As Smith described it, CMIF's was essentially an ecumenical vision of a compositionally-structured, improvisation-pervaded music informed by the musical cultures of Africa, the Americas, Asia and Europe—an admirably broad-minded vision that was inclusive in the most generous sense of the word. Although at its founding CMIF was made up of musicians working with Western instruments within predominantly Western-developed forms, one of the group's goals was eventually to incorporate into the Creative Improvisors Orchestra instruments and performers representing the world's various musical traditions. Some of the members had already taken steps in that direction: in New Dalta Ahkri, for instance, Brown played Ghanian flute in addition to bass and Smith played Indian and bamboo flutes as well as various percussion instruments; in addition, the Creative Improvisors Orchestra percussion section included gongs and other non-Western instruments as well.

The music on The Sky Cries the Blues finds the group playing works that, featuring structures more complex than the basic head-improvisations-head arrangements of much mainstream jazz, integrated elements of composition and improvisation in organic and sophisticated ways. Composition was an important part of what CMIF was about and was emphasized by Smith in particular; as Pavone remembered it, Smith encouraged members to compose. In a 1991 interview with Robert Spencer of Cadence Magazine, double bassist Joe Fonda, who recalled becoming a part of CMIF in the early 1980s—after having seen a flyer advertising for new members—also credited Smith with having had a decisive influence on his own emergent musical concepts. Encouraged by Smith and by their own backgrounds, CMIF's composer/improvisers didn't restrict themselves to a narrow set of influences but instead looked to a variety of models and sources. Although most of the musicians on the recording were rooted in the jazz tradition—and some, like Andrews, who doesn't appear on the recording, had had classical or conservatory training as well—the influences of contemporary art music were noticeably present as well.

The four compositions realized on The Sky Cries the Blues were performed by a large orchestra: sixteen pieces on three of the four tracks, with guitar added to make seventeen on the other track. The instrumentation consisted of four brass, four reeds/woodwinds, three double basses, and five percussionists including vibes. The makeup of the orchestra ensured a broad compass and a wide gamut of instrumental colors, all of which were used to good effect. Of the four compositions on the album, two were contributed by Smith and one each by Hemingway and Naughton.

Smith's "Black Fire in Mother-Land My Soul," the opening tracks, is an art song that plays on the contrasts of instrumental voices by setting out short, asymmetrical themes that serve to separate the choirs of brass, woodwinds and strings, to which is added Harryson Buster's voice. "Return to My Native Land II," also by Smith, provides further evidence of his skill as a colorist. The piece begins with the rattle of percussion and moves into sets of dissonant chords built up from the fused timbres of brass and woodwinds. Lines for vibes and a drum interlude add a further layer of timbral contrast, as do the series of sparsely accompanied solos for saxophone and bass clarinet. The percussion-thick passage towards the close makes an effective allusion to the group's interest in non-Western traditions of polyrhythms.

Hemingway's "The Interstices of a Dream (for Henry Miller)" is a tension-maintaining piece built on the dark undertow of a recurring drone played by the basses. Like a dream it proceeds as a montage of uncannily juxtaposed and changing moods. Hemingway mixes composed and improvised parts to create introspective and expressive passages, which are thrown into relief by a duet for guitar and saxophone and solos for drums and bass clarinet.

A Phrygian figure in a steady pulse played by the three-bass section of Wes Brown, Joe Fonda and Mario Pavone opens Naughton's "Picnic Wobble," the final track on the album. In contrast to the predominantly episodic pieces that precede it on the album, it largely maintains the continuity of its steady pulse throughout, while allowing for breaks into brief solo statements from many of the players.

In all, The Sky Cries the Blues presents an ensemble playing music embodying an ambitious admixture of modernist art music's harmonic vocabulary, the forceful expressivity of avant-garde jazz improvisation, and the polyrhythmic textures of African and South Asian musics. These elements are present as well in Smith's "Two Pieces for Orchestra Set No. 3," performed in concert in December, 1982. The main melodic themes are based on pentatonic scales with a distinctly non-Western flavor, while the orchestral parts supporting the soloists feature dense, chromatic harmonies and complex blends of instrumental color. Here once again, the composed and improvised elements are set up in a fruitful relationship of correspondence and mutual illumination.

The concert at which "Two Pieces for Orchestra Set No. 3" was presented was held to mark the fifth anniversary of the New Haven collective. The concert, which was sponsored by the Hartford Jazz Society, took place on 5 December 1982 at the Hartford Holiday Inn on Morgan Street and was notable for its having brought together CMIF and AACM—a meeting of two branches of the same musical family, in a sense. The ensemble for the occasion was billed as a 25-piece orchestra composed of sixteen members of CMIF plus members of AACM; representing the latter organization were Muhal Richard Abrams, Amina Claudine Myers and Leroy Jenkins, as well as Anthony Braxton—who by the mid-1980s would himself be resident in the New Haven area. In addition to featuring music by Smith, Naughton, Hemingway, Abrams and Braxton, the concert—in a kind of echo of the 1975 concert that provided the early impetus out which CMIF was formed—included arrangements of compositions by Duke Ellington.

The CMIF/AACM joint concert was just one of many concerts and performances that the New Haven group presented during its seven year existence. As with the joint concert, some featured invited work by non-CMIF artists such as Carla Bley, Slide Hampton and Randy Weston. A particularly ambitious presentation—the '81 Autumn Fest—took place over the course of nine days in October and November, 1981 and was held at venues in the Connecticut cities of Bridgeport, Litchfield and Waterbury in addition to New Haven and Hartford. Underwritten in part by the National Endowment for the Arts, this series of concerts featured CMIF's Creative Improvisors Orchestra as well as performances by individual members under their own names, and also included outside artists such as Peter Kowald, Henry Threadgill, and Fred Hopkins. In the Cadence interview Fonda even recalled one memorable program that included a string quartet.

CMIF's exchanges with artists outside of the New Haven area—many of whom were then based in New York—is emblematic not only of the strength of community binding creative musicians from different parts of the country (although it certainly was that), but of New Haven's peculiar geographical situation and the ramifications that situation has had for the city's artistic life. About halfway between Boston to the northeast and New York City to the southwest, New Haven has often served as a point of transit for artists ultimately going elsewhere. This, combined with the status of Yale students as temporary residents—and consequently as temporary participants in local artistic communities—helped give the New Haven creative music community a transient character. Even during CMIF's peak, the creative music community saw a good deal of turnover as musicians moved around, many of them to New York. Thus although transience was one of the factors that helped make CMIF, it also ultimately helped to undo CMIF. By the time the organization was disbanded in 1984, many of its members had relocated to New York and beyond.

Not only the transience of the artists, but the effort needed to sustain such a self-reliant collective—what we now would call a DIY organization—helped bring about CMIF's end. That effort was considerable, and consisted of the work that had to go into writing grant applications and pursuing other fundraising activities, securing performance opportunities, and arranging for out-of-town artists' participation in CMIF activities. And all of this on top of maintaining the creative work that was the organization's reason for being in the first place. Naughton, talking to the New York City Jazz Record, remembered CMIF as something "time-consuming and difficult to sustain;" it isn't surprising that by 1984 he'd had enough of the administrative burden of keeping a non-profit organization viable.

Although relatively short-lived, CMIF left a rich legacy. Part of that legacy survives in recordings done at the time by its members, some of which have recently been reissued. Beyond the intrinsic value of the music they contain, these recordings capture some of the spirit of collaboration and connection that the organization helped to create and nurture. The other, longer-lasting aspect of CMIF's legacy is the formative influence it had on a generation of creative musicians many of whom continue to be active and who themselves played a role in influencing new generations of artists, whether directly through teaching and personal example or indirectly through their recorded work and live performances.

Photo credit: New Dalta Ahkri at Yale's Sprague Hall (left to right: Leo Smith, Wes Brown, Bobby Naughton, Dwight Andrews). Photo by Ian Straker.

Tags

History of Jazz

Daniel Barbiero

Anthony Davis

Jane Ira Bloom

George Lewis

Leo Smith

Bobby Naughton

Dwight Andrews

Wes Brown

Gerry Hemingway

anthony braxton

Leroy Jenkins

Pheeroan AkLaff

john zorn

Oliver Lake

Perry Robinson

George Russell

Jay Hoggard

Nat Adderley, Jr.

Chick Corea

duke ellington

Mario Pavone

Joe Fonda

Harryson Buster

Muhal Richard Abrams

Amina Claudine Myers

carla bley

Slide Hampton

Randy Weston

Peter Kowald

Henry Threadgill

Fred Hopkins

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.