Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Dickie Landry: From Lafayette to the New York Loft Scene

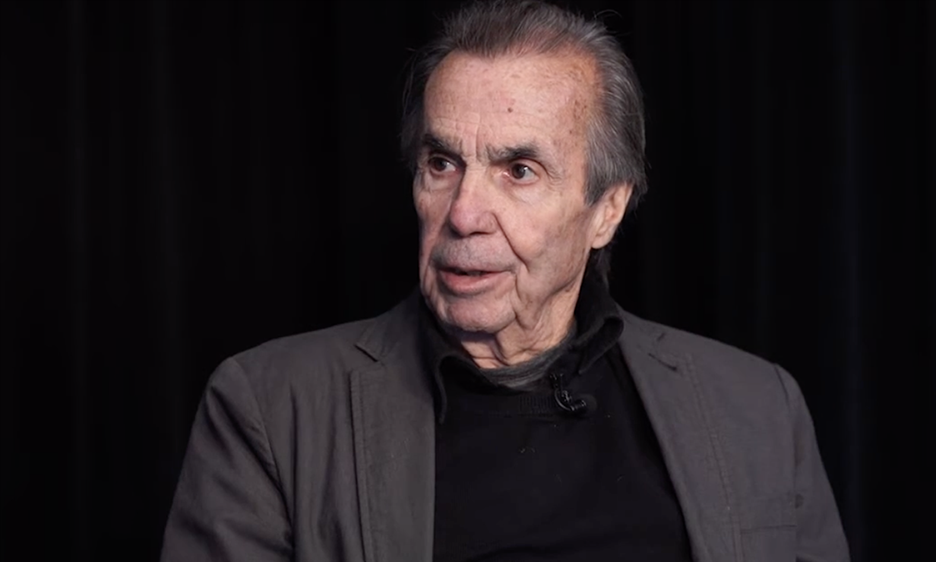

Dickie Landry: From Lafayette to the New York Loft Scene

Courtesy Dickie Landry

Like a modern-day avant-garde, musical Zelig, he has shared time in art galleries in addition to offstage, onstage and backstage with veritable icons of the period in New York.

Early Days in Louisiana

Having often deflected questions about his career with "I'm still trying to figure out who I want to be and what I want to do"—he now reflects on his life and career with a growing sense of wonder. In the early days, he played with the Swing Kings—a blue-eyed soul band that was "much better than the Muscle Shoals band," he said, continuing with "I needed work and when they asked me to come play, I immediately joined them." The Swing Kings traveled a small three-parish area in Louisiana, opening for headliners including Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave as well as Bobby Blue Bland.Asked about Redding, Landry replied:

I got to know Otis very well too; we became friends; he was a sweetheart. When he returned from California after playing a Monterey Pop, he was famous. I asked him 'What does fame do for a guy like you?' He said, 'Watch this,' called his band members over and asked them to help him dress. Without a second thought, they got him into his clothes, tied his tie and more, then he looked at me, laughing—'That's what fame does!'

Landry never had to think about what fame would do for him, as he has comfortably receded into the shadows of his own very eclectic now storied career.

The Decisive Move to New York

Though he had visited New York often enough, Bland urged him to make the decisive move.It was right after Martin Luther King got killed. I wanted to talk to him. I went to his bus but the guard said, there's no white people allowed inside. At that moment, I heard Bobby say 'Let that white boy in.' He was sitting there with a towel around his waist, smiling and praising our band, 'Man, I really liked the way y'all covered my music.' After more conversation, I said, 'Bobby, I'd like to ask you a question. Should I stay here or go to New York?' With no hesitation, he responded with get the f—k outta here!

Within a year, Landry relocated.

His already developed interest in art and natural ear for new music inevitably led him to the apex of the avant-garde scene in New York. "As a junior in the university here in Louisiana, I took an art class taught by Calvin Harlan who subsequently introduced me to Keith Sonnier. Keith had attended Rutgers University and was already living in New York City when I arrived in 1969. Sonnier eventually introduced me to Philip Glass, who then introduced me to the likes of Robert Rauschenberg and Richard Serra. And the rest is history. I was too naïve to realize I had arrived at the top of the art world already."

After a dinner at composer Steve Reich's home, upon hearing what Glass introduced as a short piano composition that lasted 45 minutes. "I jumped up and said this is the best new music I've heard in long time." From that encounter, the die was cast as Glass invited Landry to join him though, at the time, gigs were few and far between. It did not take long to recognize the limitations of a band with gifted composers who "were not very good players," Landry remarked.

I said,' Philip, we gotta make the music faster, faster, faster' and he paid attention. One by one, my friends came up from Louisiana to audition for him and were immediately hired. Eventually seven Cajun players from Lafayette played with the early ensemble.

These Louisiana musicians inherently understood the value of engagement with an audience—the power of performance—transforming the ensemble from a staid, scripted stage presence into a captivating live band. Some might consider his tenure with Glass as a career path highlight but given where he has been and what he has achieved since that time, it is still up for conversation.

Modern-Day Avant-Garde Zelig

Like a modern-day avant-garde, musical Zelig, he has shared time in art galleries in addition to offstage, onstage and backstage with veritable icons of the period in New York. His stories are full of chance meetings like these:I first met Laurie Anderson in 1969, soon after arriving in New York. Gordon Mattaclark organized a monthly salon inviting artists and others to come to discuss their projects and offer ideas, and in walks this beautiful little girl carrying a camouflage violin case. I said, 'Oh you play violin, why don't you play for us.' A bit flustered, she hurriedly responded 'No, no, no' and sat down.' She was in the Holly Soloman gallery when one day Holly's husband Horace, said, 'I have a new tape by Laurie. I want you to give me your opinion.' We went down to his car to listen to the tape. And when it finished, I said, 'Release this immediately.' O Superman went to the number two on the top hits chart in London the next week. In June, 2025 I was invited to exhibit drawings, paintings and videos at the Hunter Dunbar Project in New York where I'm also playing a 45 minute concert and Laurie has agreed to play a duet with me. We go back a long way.

His friendship with Paul Simon began by chance as well. After initially introducing him to Buckwheat Zydeco as a stand in for an ill Clifton Chenier on a recording session, Simon invited Landry into the studio to hear what he was working on. With the taped music running in the background, Simon leaned over to sing in his ear. Asked for feedback, Landry pleaded ignorance—"I respect you as a musician and songwriter, but I never bought one of your records. And here you are, singing in my ear and it's not Memorex." Asked for further comment about the lyrics, Landry responded "I'm a musician, I don't listen to lyrics." But he eventually relented, jotting down a few thoughts on a piece of paper. Later that evening over dinner, Simon thanked Landry for the honest critique, and they've remained close friends ever since.

Paul McCartney

Fond of cooking as many in Louisiana are, he has done so for Paul McCartney too. "I was staying with Paul Simon at his beach house, in Montauk on Long Island. And I like to cook and made a cream corn dish for Paul. A couple days later, he said, 'I'm having the McCartney's over for dinner tomorrow night. Why don't you cook your cream corn for them?" As he began preparing the evening meal, "McCartney walked into the kitchen, saying, you must be that Cajun man who's preparing that cream corn dish for us. 'Yes, sir, that's me.' Landry continued with the tale:We sat down to eat—the summer corn was amazingly sweet and the conversation was good too—when he said if you're in London, call us and come on over. Unconvinced, 'Yeah, right—like I'm going to call and say 'Hey, Paul, it's Dickie Landry and I'm in town.' Paul insisted he was serious. 'You just cooked a dish that I've never had and you're friends with Paul and his wife, so come visit us when you're in London.' As fate would have it, I had to run as Terrence Simien's zydeco band had a show, and I was their manager at the time. Excusing myself early, Paul looked at his two daughters, and asked if they wanted to go see some Louisiana music. Naturally, I invited them to come along, they had a great time, and I got them back home at six o'clock in the morning! And they didn't even have to sneak back into the house!

Bob Dylan

But appearing at Jazz Fest with Bob Dylan in 2003 was an opportunity he never sought or expected either. He related it to AAJ this way:Kerry Boutte, owner of Mulate's Restaurant in New Orleans, was friends with Bob and invited him to a private dinner at the restaurant and asked me to come as well. Arriving a bit early, I was standing around with some of the chefs and Tony Garnier, Bob's bassist. As Bob walked in, he saw people who he didn't recognize. He's an introvert and turned to leave when Tony hurried over, urging him to come in. 'You must meet Dickie Landry. He's played with Philip Glass and Laurie Anderson.

Relenting, he approached us standing around at the table, wondering aloud who and where is this Dickie Landry. 'I'm right here. How you doing, sir?' You must have interesting stories,' he said. Agreeing, I asked, 'Where do you want me to begin?' Asking how I met Philip. I told him we had started out as plumbers together. Looking at me in disbelief, I added 'Yeah, while you were making millions, we were struggling, but I want to hear your stories; mine can't be as good as yours.' So, we sat down to enjoy our dinner and talked. As I told him about sitting in with Hank Williams III for a punk rock set, Bob stopped me, asking 'How'd you follow those musicians?' Informing him that even in punk rock, there's a structure and they gave cues with their body movements, he looked at me, 'My music is structured, so what are you doing tomorrow night?' 'What do you mean?,' he asked. He wanted me to come with my sax for the full set, all 16 songs! I looked at him, 'Bob, I don't know any of your music.' But who tells Bob Dylan they don't know his music? So I asked, 'What am I'm going to do?' Bob's cryptic response, 'Stand by me.' Without missing a beat, I told him, 'I know that song, but you didn't write it!' By this time, he's sitting there smiling while his managers were horrified, audibly gasping for air.

We finished eating, but before leaving I caught up with Tony and asked if Bob was serious. Told to check back the next morning, Tony answered when I called and told me Bob was wondering what time I'd show up. Upon arriving, Garnier offered the only advice he could—'Just keep your eyes on Bob, he'll give you cues when to step out and play.' After some conversation, Bob asked me to lead him out on the stage and together we emerged. When I realized he wanted me dead center directly next to him with the band behind us, I could barely catch my breath. I've never been so nervous. At one point during the set, the lights softened as Tony whispered in my ear Bob was going to sing a folk song not suited for a sax solo.

So I left the stage but was told to return for the next song. Upon resuming my place, he turned and said, 'Where'd you go? It's my band, don't leave again!' I got through the set fine and while accompanying him to the bus afterward, I thanked him for the opportunity to perform. I can still see his steely blue eyes and hear his words in my head: "Anytime." And to this day, I wonder—Why me? No one ever sits in with Bob Dylan!

Landry paused for a moment, reliving the moment but responded to the suggestion that perhaps Dylan was intrigued to meet someone who didn't know his music, he shrugged his shoulders, not completely convinced.

Closer to Home

But memories of mixing with the stars from afar does not discount encounters with those closer to home.Art Neville was a good friend, and according to him, we're cousins! I walked into a club in Baton Rouge one night, and Art calls out in my direction, 'Hey, cuz—hey cuz.' I turned and saw him and asked, 'What this shit about—cuz, cuz?' He said, 'We're cousins, because my mama was a Landry from Clinton and your father was a Landry, born right across the river in St. Francisville, so we're cousins. And that's that.'

A year later at Jazz Fest, I was doing a soundcheck for Aaron Neville and Paul Simon as they were performing together. I told Aaron what his brother had said. In a very serious tone of voice, Aaron agreed—'If Art said that, it must be true.' And years later, Cyril Neville introduced me to his then teenage kids as one of their cousins!

What further proof does one need to understand Landry's place among the many musical icons in New Orleans? He is virtually a card-carrying member of the first family of funk!

And he became close friends with the legendary king of zydeco.

I first met Clifton Chenier in 1972 after the filming of Les Blank's 'Hot Pepper.' A friend of mine took me to hear Chenier play at a small, all black club in the swamps of southwest Louisiana, the Dixie Doodle. I was a bit apprehensive but was told it was ok, not to worry. John Hart, a saxophonist friend of mine was onstage, and I asked if I could sit in with them. John leaned over to ask Clif if I could join them saying 'Hey boys, we got a white boy from Cecilia who wants try and play.' Little did I know it was a nonstop, four-hour gig. After two hours, I was getting tired and thought to leave. 'Hey white boy, you can do the zydeco, so please stay.' Apparently even if you left to go to the bathroom, it was understood that you just kept on going. So I stayed and we remained friends ever since that night so long ago.

With a taste in music that has rarely been mainstream, upon meeting McCartney, he failed to add he had never cared for The Beatles. Though the daughters of close friends were heads over heels for them, he never understood why. And when asked what he listens to these days, he replied, "I'm up to here with music [gesturing to his forehead] and cannot listen any longer." Settling back in his chair, he added, "but I'll listen to KRVS (FM 88.7, Lafayette) as they broadcast a wonderful zydeco show every Saturday morning. Tune in and you'll get an ear full!" A photographer of note as well, he was hanging out with an elite cast of artists in New York in the early '70s, was given a camera and took some shots. Often asked to exhibit his photographs (as well as his paintings), he has sold prints over the years and exhibited his shots documenting that wondrously creative period in the early '70s of the avant-garde art scene in New York. Due to exhibit photographs at the Smith Gallery on Julia Street in New Orleans in fall of 2025, he is also looking forward to a showing of his paintings at the O'Keefe Gallery in Biloxi, Mississippi.

Mick Jagger

A photo taken at Jay's Lounge & Cock Pit in Cankton, Louisiana (also a venue for fighting roosters) graces the cover of a Chenier tribute album. Released in late June 2025 to commemorate Chenier's 100th birthday, Landry is partially responsible for the addition of Mick Jagger to that star-studded cast who contributed to the project. His meeting with Jagger was another fortuitous event:I first met Jagger in Los Angeles, sort of by chance. It was my 40th birthday and had finished a concert with Phillip Glass at the Whiskey A-Go-Go. We returned to a house in Brentwood where we were staying and was met with a surprise party. Told there was someone famous in the back room talking bad about birthdays in general, I went back there to investigate, and that famous someone was Mick Jagger. Approaching him, I said be nice, that It's my 40th birthday. Scoffing he, said he was 37 and probably wouldn't live to see his 40th. I told him, 'f—k off' and left the room.

The next night, in a restaurant where us members of the Phillip Glass Ensemble were eating, the Stones' manager approached me—I knew him from New York—and invited me into a private back room to join them after their guests leave. I entered the room where Jagger, two women and their manager were, sat down when Mick asked me where I was from. I proudly told him I was from south Louisiana. He immediately interjected, 'Clifton Chenier—the best band I've heard in my life and would love to hear them again!' Telling him, 'You're in luck, he's playing at a high school over in Watts tomorrow night.' Jagger asked if I could set it up for them to meet. I called Clifton and told him I'd come over with someone from The Rolling Stones.'

'Rolling Stones? Oh yeah, that magazine, they wrote an article about me once, bring 'em on over!'

We arrived the next night, and I walked in first to get the lay of the place—it looked like a zydeco club right out of southwest Louisiana. To my surprise, people were speaking French and upon asking how that was possible, the story came out that their parents had moved from Louisiana ot Los Angeles to help build ships for the Navy during World War II.

I escorted Mick in, introduced him to Clifton who still had no idea who Mick Jagger was nor did anyone who was at that show. During the intermission with a crowd beginning to descend on the star of the show, Jagger was afraid of being recognized though I assured him he would be safe. A group of people approached with pens and paper in hand, as Jagger took a step back, saying 'I'm not working tonight' meaning he wasn't signing autographs. Taking his hand to reassure him, I told him to be still as the crowd rushed by us without a second glance, focusing their attention on Clifton. Mick looked up at me, smiling, 'No one's going to believe this story.'

Fast forward to last year at Jazz Fest and the Stones were in town to perform. I had a solo appearance at Chickie Wah Wah the night before and told the story of taking Mick to meet Clifton. Mick's kids were in the audience and apparently returned to tell their dad what they had seen and heard. As it happened, CC Adcock had arranged for a luncheon at Antoine's (in the French Quarter) for his English friends, invited me and word had it that Mick might be there too. I arrived late, and entering the dark restaurant from the bright light of day outside, it took a moment for my eyes to adjust. Upon entering, someone announced, 'Dickie Landry's in the house!' when suddenly a guy comes up to me. I had to look twice and sure enough, it was Mick. We embraced and sat down to talk about that chance meeting so long ago. Asking him if he remembered that night 40 years ago, he responded—'Like it was yesterday.'

We continued talking for some time and finally decided it was time leave. Mick escorted me to the door, where CC was standing. I said good-bye to them both when CC happened to mention Arhoolie Records was putting out a tribute album to Clifton. Without hesitating, Mick said he wanted to sing on it. And it happened. CC invited Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood to play too. It is the first tribute album they've ever played on and Mick was great, singing in French and playing harmonica too. When I heard the final mix, I was blown away.

The cut appears on the album A Tribute to the King of Zydeco (Valcour Records, 2025). It was also released as a single, with Mick singing in French on Clifton's 'Zydeco Son Pas Salés' and Clifton's original recording, dating to 1965, on the other side.

Back in Lafayette

Upon re-locating to Lafayette after many years away, Landry unexpectedly returned to his swamp pop roots, joining a local supergroup—Lil Band O' Gold—with accordionist Steve Riley , drummer Warren Storm, and CC Adcock. He told AAJ the story of his return:I left Louisiana 50 years before to get away from that kind of music, but it was one of the greatest bands I've ever played with besides Philip Glass. When I moved back from New York, my next-door neighbor was CC, when he decided to put a band together with the legendary drummer, Warren Storm, who had major hits in the early fifties. So we went over together and asked him to join the group. Warren, undecided, pulled me aside to ask if I was going to be in the band too. I said, 'Yeah, I think I am. 'Ok, if you're in, I'll play too, but on one condition—you have to buy me a set of drums and you have to set up the drums and tear them down too.'

That first night, the first gig we had, I arrived at the club to discover he didn't even have a pair of drumsticks! Forced to run back to my apartment, I got the only drumsticks I had, ones that once belonged to Miles Davis' drummer! Warren's a great singer and a great drummer too. We toured Australia, some of Europe and America too. But then people started dying so we had to stop; it was a great band though.

What has he not done and who does he not know? Inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame in 2018, awarded an honorary doctorate from University of Louisiana, Lafayette in 2025, he has been widely lauded for his long, illustrious career. Still, few outside Louisiana (and New York) are fully aware of this talented musician, artist and photographer. Not that he shuns attention, but he does not seek it either.

Described by New Orleans drummer Johnny Vidacovich as "avant-garde—he's been ahead of everyone else forever, even ahead of himself," Landry continues to command great respect among his peers. With remarkably diverse interests, by the sheer luck of the draw and fortuitous twists of fate, his life has been an incredibly rich and unusual one shared with a plethora of talented individuals over the past sixty years. And it continues.

Tags

Interview

Dickie Landry

Thomas Cole

United States

Louisiana

New Orleans

Otis Redding

Wilson Pickett

Sam & Dave

Bobby "Blue" Bland.

Bobby "Blue" Bland

Philip Glass

Steve Reich's

Laurie Anderson

Paul Simon

Buckwheat Zydeco

Clifton Chenier

Paul McCartney

Terrence Simien's

Bob Dylan

Tony Garnier

Art Neville

Aaron Neville

Cyril

John Hart

Mick Jagger

Rolling Stones

CC Adcock

Keith

Ronnie

Steve Riley

Warren Storm

C.C Adcock

Johnny Vidacovich

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.